|

by Alex E. Body August 2019 |

Foreword

Few bands in the history of rock music inspire such polarised opinion as Rush. From their modest beginnings as a blues rock cover band playing small bars in Toronto, Rush's career was built on the firm foundation of constant touring. Originally forming in 1968 as high school friends - guitarist Alex Lifeson, drummer John Rutsey, and singer and bassist Jeff Jones - it was not until 1971 that Geddy Lee would join the band, replacing Jones to create the original line-up. Rutsey would remain in the band until 1974 when he was replaced by Neil Peart, thus creating the definitive Rush line-up. Since 1974, Rush's line-up has not changed.

Even from their earliest days, the band developed and changed constantly, losing and gaining fans along the way - but famously retaining their integrity - always moving in the direction that they chose.

In this book, I have tried to follow the journey of Rush through their compositions, tracing the origins of some of the band's unexpected (and sometimes unpopular) changes of style, as well as highlighting the band's great achievements along the way. The writing is deliberately as objective as possible, although, due to the nature of music, this has not always been possible. Nevertheless, this is a book designed to reveal the inner workings and background behind the band's enormous repertoire; it is not a review of it.

Rush were known for many years as 'the world's biggest cult band'; indeed, with twenty-four gold records and fourteen platinum records, they are only succeeded by The Beatles and The Rolling Stones for the most consecutive gold or platinum studio albums by a rock band.

As the band's enormous influence on modern rock music became evident in the twenty-first century, Rush are now regarded by rock fans and musicians alike as one of the most important rock acts to ever come out of North America. After more than forty years of writing and touring, in 2017, it seems that the band may finally be at the end of their career. Rush fans, however, know that the only thing to expect from Rush is the unexpected.

Author's note: Given the stability of the band's line-up I have chosen not to list the line-up against each album. As a result, the reader should assume the line up to be, unless shown otherwise:

Geddy Lee: bass, vocals, keyboards

Alex Lifeson: guitars

Neil Peart: drums and percussion.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Stephen Lambe for support and advice along the way. Alex Dunbar, Mitch Simpson, Sebastiaan van Stijn, and Tim Stance for their photographs and memorabilia, my mum and dad for 'getting the ball rolling', and Audrey for her enduring patience.

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

1 Rush

2 Fly by Night

3 Caress of Steel

4 2112

5 A Farewell to Kings

6 Hemispheres

7 Permanent Waves

8 Moving Pictures

9 Signals

10 Grace Under Pressure

11 Power Windows

12 Hold Your Fire

13 Presto

14 Roll the Bones

15 Counterparts

16 Test for Echo

17 Vapor Trails

18 Snakes and Arrows

19 Clockwork Angels

20 Live Albums, Solo Albums, and Curiosities

Endnotes

Bibliography

Rush

Current edition: Virgin / EMI CD

Personnel: John Rutsey - drums

Recorded at Toronto Sound Studios and Eastern Sound

Produced by Rush, remixed by Terry Brown

Chart position: Canada: 86 UK: Did not chart US: 105

In 1973, Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, and John Rutsey recorded their eponymous album: Rush. Initially released in Canada on their own vanity label, Moon Records, the album was met with good local reception although the initial pressing of 3,500 units seemed ample.

However, shortly after the album's release in 1974, a Cleveland DJ, Donna Halper, added the song 'Working Man to her regular playlist. This decision was arguably the single most important of Rush's career. Cleveland, a factory town, immediately took to the song, telephoning the station in droves whenever the song was played - often convinced that the track was a new Led Zeppelin single. This unexpected reaction led to the signing of Rush to the major label Mercury, which distributed the album in the USA and subsequently internationally - though not until some changes had been made.

The recording had initially been done on a tight budget with the band laying down tracks at Toronto's Eastern Sound on an outdated 8-track recorder. These sessions were done overnight during the studios 'dead' period to further reduce the financial outlay. Unhappy with the results, overdubs - and some new tracks - were recorded at Toronto Sound Studios where the band produced themselves and were happier with the result, but this was not the record Mercury wanted to put out. Rush's manager Ray Danniels agreed to fund the recruitment of Terry Brown to perform a remix. Brown would produce eight subsequent Rush albums and was often referred to as the band's fourth member. Another incredibly fortunate turn in Rush's career had just occurred.

This is the only Rush album on which original drummer John Rutsey performs. His solid rock drumming is a cornerstone of the original Rush sound, but, like many rock drummers of the time, he was reliable rather than spectacular. His musical interests leant more towards the traditional hard rock of the time, while Lee and Lifeson hoped to take their music into more progressive territory. It was, however, Rutsey's health that would eventually cause his split from the band. Unable to cope with an unforgiving touring schedule, his diabetes forced him to part ways with Rush.

This debut is often poorly reviewed by those who have written about it since the release of Rush's most popular material, and in the context of their other great work, this is understandable, but Rush is an energetic and exciting rock album that in 1974 deserved its enthusiastic praise.

Like almost every Rush album, their debut is an album that was hugely influenced by the musical styles that were in fashion at the time. On first listen, it is easy to dismiss this as another good but ultimately ordinary hard rock album. On closer inspection, however, there is much in this album that shows a band that have the potential to do great things.

While the album's lyrics do leave something to be desired, this is partially the responsibility of John Rutsey who was in fact the band's original lyricist. Shortly before entering the studio, Rutsey had a sudden lack of confidence in his work and ripped up the paper that his words were written on. With time short, it fell to Lee to write an album of lyrics in an extremely short space of time, or else waste the band's valuable studio time.

The drumming on the album, though competent, lacks the inventiveness and style on display from the bass and guitar and so it is unsurprising that the album's two weakest points - the drumming and the lyrics - would, on the next album, be the responsibility of a new band member: Neil Peart.

Songs

'Finding My Way'

Alex Lifeson's distorted guitar slowly fades in interspersing huge Townshend-esque chords with a frantic three-note repeating lick. After a couple of measures, the listener is introduced to Geddy Lee's signature mid-70s wail. This vocal style, which came naturally to Lee, was described at the time by various critics as sounding like 'a hamster in overdrive, 'the dead howling in Hades, 'strangling a hamster, and 'a cat being chased out the door with a blow torch up its ass, but was also, more kindly (and quite understandably), compared to Robert Plant's high register.

Alex Lifeson's distorted guitar slowly fades in interspersing huge Townshend-esque chords with a frantic three-note repeating lick. After a couple of measures, the listener is introduced to Geddy Lee's signature mid-70s wail. This vocal style, which came naturally to Lee, was described at the time by various critics as sounding like 'a hamster in overdrive, 'the dead howling in Hades, 'strangling a hamster, and 'a cat being chased out the door with a blow torch up its ass, but was also, more kindly (and quite understandably), compared to Robert Plant's high register.

The bass tone here is, for the era, unusually crisp and has a 'twang' that, among Rush's 1974 contemporaries, could only be found growling out of John Entwistle's amplifiers. It is no secret that Rush were massively influenced by bands of the 'British invasion and the first few seconds of this debut make that statement loud and clear. After the thrilling intro, the song becomes a more standard affair for the era - albeit one with an unusually punchy and energetic sound, especially for a trio.

The lyric to 'Finding my Way' is simple, but one of the more meaningful on the album. Lines like 'I've been here so long/Lost count of the years' speak of the impatient young man desperate to escape the small town life. This sentiment would later be expressed, on numerous occasions, far more eloquently by their future lyricist, Neil Peart.

On listening to 'Finding My Way' with a knowledge of Rush's entire discography, each member sounds much more like their influences than the musicians they would in time become: Lee playing bass like Jack Bruce and John Entwistle while singing like Robert Plant and Lifeson doing his best imitation of Jimmy Page and Pete Townshend.

'Need Some Love'

A punchy start to an upbeat song that is, in many ways, indistinguishable from the fare on offer from most other mid-70s hard rock bands. The lyrics are particularly unadventurous ('Ooh I need some love/I said I need some love/Ooh I need some love'), especially when compared to the ambitious work that would later define the band.

Here Rutsey sounds completely at home driving the song along and performing effective rock fills. It is perhaps telling that it is on the more straightforward tracks that this is most evident. On this track, Lee begins to hint at the exceptional bass playing he is capable of. Subtle melodic runs and intricate bass lines that are a world away from the root note plodding that listeners had come to expect from many rock bands. Lifeson delivers a punchy and energetic solo that has hints of the off-kilter style he would later become known for.

With a duration of two minutes and nineteen seconds, 'Need Some Love' is over before it is possible to be bored of it, but the song is probably not one many Rush fans would remark on.

'Take a Friend'

Another fade in here, but with an odd repeating riff of the type Rush would become famous for in later years. This intro is perhaps the most interesting part of this otherwise laid-back blues-rock tune. The intro is followed by an unmistakably Led Zeppelin inspired riff, which forms the basis of the verse. A cheerful melodic chorus lifts the song and Lifeson comfortably slots in his lead licks around Lee's now slightly more reserved vocals.

It is worth noting that, yet again, the song writing here is very lean: before the two-minute mark, we have already had an intro, two verses, and two choruses.

Although much of this album sounds initially similar to many other bands of the time, the song writing offers little opportunity for the listener to be bored. While other bands may stay with a theme for minutes at a time, even at this stage of their career, Rush seem keen to develop ideas quickly and move on - a strength that has stayed with them as songwriters throughout their long career.

As well as Lifeson's Zeppelin-esque riffing on 'Take a Friend', Lee's vocal develops into a crescendo of 'yeah-yeahs’, which are, deliberately or not, so obviously a style picked up from Robert Plant. The effect is absolutely hammered home, however, with some gratuitous use of tape-delay causing Geddy's counter-tenor to echo across the track before Lifeson's riffing begins again.

The lyric to 'Take a Friend' is another extremely simple one: the three verses are ostensibly the same piece of writing with just the phrasing changed. There are no deep metaphors or double meanings here: 'Take yourself a friend/Keep 'em 'til the end/Whether woman or man/It makes you feel so good'.

'Here Again'

A sullen, down tempo riff opens this moody track. Lee's crystal clear bass plays a neat run over Rutsey's laid-back drums as the singing begins. The vocal performance here gradually builds from its reserved beginnings to an impassioned shriek. This is one of the few times in the album where the budget constraints are evident; if they had been signed to a major label when recording this, perhaps such vocal performances could have been perfected before pressing. In any case, here we have a moment in time: three young musicians recording their debut LP, with Lee quite literally still finding his voice.

The lyric here is a little more interesting and certainly makes an attempt to transcend the far more pedestrian work that makes up the rest of the album: 'Yes, you know that the hardest part/Yes, I say it is to stay on top/On top of a world forever churning'.

The lyric here is a little more interesting and certainly makes an attempt to transcend the far more pedestrian work that makes up the rest of the album: 'Yes, you know that the hardest part/Yes, I say it is to stay on top/On top of a world forever churning'.

Once again, although we are listening to what is essentially a prototype of Rush, this idea of constantly progressing is a theme that occurs time and time again both in the band's future lyrics and indeed has been expressed regularly by the band in interviews. It should perhaps not be surprising that this notion has made it into the band's work so early in their career.

The entire first half of the song is a brooding build up. Lifeson's compelling chord work and Lee's earnest singing successfully produces tension that has its worthy release after four minutes. Another simple drum fill takes the song into its uplifting chorus, which shows a maturity in composition unseen in the previous three tracks. Lifeson's famously free and avant-garde lead style seems moderated and slightly stilted during the song's guitar solo finale; this is perhaps another example of a time when more studio time would have allowed the song's performances to be fine-tuned.

Clocking in at seven minutes and thirty-five seconds, this song could arguably have been trimmed. However, extended pieces would become a signature part of Rush's catalogue and experimentations with over-long songs at this early stage of their career may have directly led to the extraordinary compositions they would later produce.

'What You're Doing'

The second side of Rush opens with an immediate and arresting riff contrasting neatly with the down tempo end of the first side. The bass and guitar are in perfect unison here providing the huge rock sound Rush were famous for in their early days.

The lyrics here are a rehash of many 'stick it to the man'-type lyrics that were common place during the late '60s and early '70s, and although they do not quite say anything in particular, this youthful rebellious song, particularly with Lee's enthusiastic delivery, is very entertaining.

The most exciting thing about this song is the instrumental fills. Between the standard bluesy verses, all three musicians perform fast and intricate runs that elevate the song from an amusing blues-rock number into something thrilling. If you are listening to this album with knowledge of Rush's later work, 'What You're Doing' is probably the most easily identifiable as having the Rush sound.

It is also worth mentioning that the lead guitar work here seems far freer and more expressive than on the previous songs. The faster pace, heavier sound, and greater energy perhaps providing a better foundation for Lifeson to build his solos on.

'In the Mood'

While every other song on the album is a Lee and Lifeson collaboration, 'In the Mood' is a pure Geddy Lee composition.

A strong vocal melody counterpointed cleverly by Lifeson's riffs make for a memorable pop song. Understandable then that this is one of the few songs from Rush's debut that made regular appearances in Rush live sets well into their career - often as part of a medley in the encore.

Rutsey's drumming here is careful and precise with interesting fills and changes in dynamics. A short break into a Merseybeat during the guitar solo helps make this one of Rutsey's best performances on the album. Although in 1974 it was hard to consider Geddy Lee as a particularly accomplished lyricist, his decision to rhyme 'Late' with 'Eight' actually ended up gaining the band a decent regular bit of airplay.

The St. Louis Classic Rock radio station KSHE would regularly play the song every Friday night at 7.45 p.m. in reference to the song's chorus: 'Hey baby, it's a quarter to eight/I feel I'm in the mood'.

'Before and After'

Layers of acoustic, electric and bass guitar open 'Before and After' to create a beautiful lush sound that is unique to this point in the album.

'Before and After' is the first recorded effort of Rush's style of linear songwriting. The tender opening to the song is gradually developed and builds to a dreamy apogee, which then, surprisingly, is abandoned for a complete change of direction. The subtle guitars are now gone and with a perfunctory snare roll we are back into heavy blues-rock territory once again.

The unison riffs are particularly pronounced here, weaving around Lee's vocals expertly, but the lyrics unfortunately are more of the same. This time an appeal to rescue a failing relationship in the midst of a feud. The chorus, typically, is one word repeated four times: 'yeah!'

The breakdown section later in the second half of the song is without question the most Led Zeppelin sounding moment in the album - a heavy riff stop-starts between huge, straightforward drums. Lifeson soon fills in the gaps with his best Jimmy Page impression and, in some ways surprisingly, it really works. With Lee's voice deluged in reverb and delay the song finishes with one final shriek: 'I said yeah yeah yeah yeah!'

'Working Man'

'Working Man' was the song that broke Rush. A song about the rigours of working an ordinary 9-5 job, day-in, day-out. The simple lyric is effective because it is so ambiguous - it could apply to just about anyone. This is perhaps why the population of Cleveland took to the song so enthusiastically.

The lyric does hide yet another subtle, yet important line: 'It seems to me I could live my life/A lot better than I think I am'. Ambition, and desperation to progress, is a theme once again.

The lyric does hide yet another subtle, yet important line: 'It seems to me I could live my life/A lot better than I think I am'. Ambition, and desperation to progress, is a theme once again.

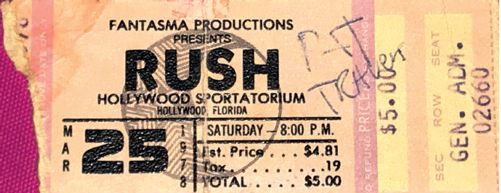

The idea of a song that is over seven minutes long being the single that successfully introduces a listening audience to a new band is so alien today, and yet it was, in those days, something Donna Halper as music director of WMMS ensured she did for her DJs. She was always on the look-out for what she called 'bathroom songs': 'I had to think about my DJs. I was always looking for long songs that were also good songs, so they [the DJs] could do what they had to do'.

The dark, baleful intro to 'Working Man' is one of the heaviest moments on the album. Reminiscent of Black Sabbath, this proto-metal track moves through several parts. Lee's vocals here are once again much more melodic forgoing the blues wailing for some powerful, yet tuneful singing.

After the second chorus, a short bass solo ushers in Lifeson's most technical solo on the album. This is a solo that ebbs and flows with bizarre almost dissonant flourishes counterpointed with tightly performed melodic runs. This is the moment on the album when the listener is offered a glimpse into the future - seeing hints of the extraordinary lead guitar player that Lifeson will become.

After the solo a fast repeating riff is played by the bass and guitar again and again building up to a crescendos segue into the song's final verse. Although much of the song writing on the album shows a band in their early days, this is a thrilling, flawless moment of rock music that the band continued to perform in the same way, note for note, right up to their final tour.

Interesting Liner Notes

A special thanks 'to Donna Halper of WMMS in Cleveland for getting the ball rolling' has been included on every reprint of Rush since its re-release on the Mercury label. Advice to the listener is also included: For best results play at maximum volume'.