|

Sports Cars of the Sixties Foreword by Carrie Nuttal-Peart November 19th, 2024 |

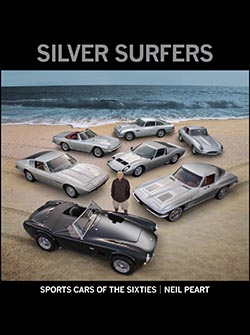

Gorgeous images of the cars and photos curated by Neil himself accompany his warm, personal story of building the collection, the friends he made along the way, and what it was like to be behind the wheel of these classics. Neil’s final work is a love letter to these cars that meant so much to him, and to the passion of the road that fueled his life.

About the Author

Widely considered one of the most innovative drummers in rock history, Neil Peart (1952-2020) was the backbone of the legendary Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame band Rush. Neil’s virtuosity behind the kit was equaled by his talent as the band’s lyricist. Affectionately dubbed “The Professor” by the fans, he tapped into his love and deep knowledge of poetry, literature, philosophy, and science to pen such classics as “The Spirit of Radio,” “Free Will,” and the self-described autobiographical “Subdivisions” and “Limelight.”

Neil’s talent for the written word, passion for the open road, and desire to chronicle milestones in his life led to the publication of seven memoirs, including Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road, Roadshow: Landscape with Drums, and Traveling Music: Playing Back the Soundtrack to My Life and Times. Collaborating with Kevin J. Anderson, Neil also wrote the novel Clockwork Angels, a fictionalization of Rush’s 2012 album of the same name, and a sequel, Clockwork Lives. Silver Surfers is the final work of Neil's long and prolific writing career.

On January 7, 2020, Neil passed away after a private, three-and-a-half-year struggle with brain cancer. He is survived by his wife Carrie, and daughter Olivia.

CEO Raoul Goff

VP CO0-Publisher Vanessa Lopez

Senior Editor Karyn Gerhard

VP Creative Director Chrissy Kwasnik

Sr Production Manager, Subsidiary Rights Lina s Palma-Temena

Text © 2024 Neil Peart

Foreword text © 2024 Carrie Nuttall-Peart

Design by Roger Gorman, Reiner Design Consultants Inc.

Project Manager for the Neil Peart Estate: Carrie Nuttall-Peart

Insight Editions, and in particular the editor, would like to extend their most heartfeit thanks to Carrie Nuttall-Peart. The amount of work she put into bringing Neil's final work to life was nothing short of extraordinary. Without her drive, passion, determination, and spirit of collaboration, this book would not have been possible.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY CARRIE NUTTALL-PEART

HERE IS WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

DRIVING AS INSPIRATION

THE CARS

1964 ASTON MARTIN DB5 SALOON

1964 JAGUAR E-TYPE FHC

1963 CHEVROLET CORVETTE STING RAY

1965 MASERATI MISTRAL SPYDER

1973 MASERATI GHIBLI SS

1970 LAMBORGHINI MIURA S

1964 SHELBY COBRA

NOW IT STARTS...

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PHOTO CREDITS

FOREWORD

by Carrie Nuttall-Peart

Neil was widely known as a legendary drummer, lyricist,

and nonfiction writer, but this complex, brilliant man was

so much more. He was a true Renaissance man; the type of

man one rarely comes across in this day and age. Neil had a

plethora of interests and passions, many of which he spent

years studying and practicing until he gained an impressive

amount of expertise. Just a few of his interests were

omithology, art, literature, nature, and grueling physical

challenges such as climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro; and of course...

cars.

Neil was widely known as a legendary drummer, lyricist,

and nonfiction writer, but this complex, brilliant man was

so much more. He was a true Renaissance man; the type of

man one rarely comes across in this day and age. Neil had a

plethora of interests and passions, many of which he spent

years studying and practicing until he gained an impressive

amount of expertise. Just a few of his interests were

omithology, art, literature, nature, and grueling physical

challenges such as climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro; and of course...

cars.

They happened to be his first passion in life, and according

to his mother, “car” was the first word he ever said. This is easy

to believe when seeing this photo of him as a one-year old,

sitting behind the wheel of his father’s '48 Pontiac, grinning ear

to ear. He inherited this particular interest from his belated

father, Glen, who passed down his knowledge and enthusiasm,

as well as exposing him to his own beloved cars. This lifelong

passion eventually resulted in his stunning, elegant, carefully

curated collection he named the “Silver Surfers.”

For years prior to his first big purchase, the DB5, we would

be reading in bed, and often I would glance over to see him

studying photos of car engines in one of the many glossy auto

magazines he loved. These images did absolutely nothing for

me, as I didn't understand at the time how a “hunk of metal"

could be so fascinating. However, I soon came to lear that as

with all of his passions, he wanted to learn every single thing he

could about cars, from engine design and function, to how and

why cars were designed, and re-designed over the decades.

Not just from an aesthetic perspective, but how these design

changes actually changed the functionality of the car.

When Neil first told me about his desire to purchase the DB5,

he said, “This is the car that I always dreamed of owning when I

was a kid! It was my dream car!” Interestingly enough, he said

the same thing about the second Silver Surfer car he

purchased, and then the third, and so on, until it became a

running joke between the two of us. I would remind him that I

think he’d said that before, and he would say, “Well, yeah, but

that was when I was this age, or that age.” and we would

always have a good laugh.

At one point, Neil had accumulated enough cars to warrant

leasing a proper storage space. When he first suggested

looking for an industrial space, I envisioned some sort of bare-

bones warehouse where the cars would be left when they were

not being driven. Perhaps one that even had air conditioning,

and of course, top-notch security. However, as Neil always said,

“if you want to do something, then you must do it properly” and

in this instance, Neil had a vision far beyond a simple

warehouse.

At one point, Neil had accumulated enough cars to warrant

leasing a proper storage space. When he first suggested

looking for an industrial space, I envisioned some sort of bare-

bones warehouse where the cars would be left when they were

not being driven. Perhaps one that even had air conditioning,

and of course, top-notch security. However, as Neil always said,

“if you want to do something, then you must do it properly” and

in this instance, Neil had a vision far beyond a simple

warehouse.

The “industrial” space ended up being a beautiful, finished

space worthy of a high-end photo studio, complete with

skylights, polished and stained concrete floors, a kitchenette,

and a lounge space for visitors. Neil’s vision continued to

expand as time passed, and he added element upon element

until he felt it was complete. Walls became filled with carefully

chosen, car-related artwork, and a variety of displays were

installed including his vast collection of car books and model

cars. This lovely space, which you will see later on in the book,

was soon dubbed the “Man-Cave,” and eventually became

known simply as, “The Cave.”

However, this was not the typical “Man-cave” one sees in

movies or is described in books. Neil was one of the most

prolific people I have ever met, and his work ethic was

legendary. This is where he went for the necessary solitude to

write and work, enjoy his cars, and have friends over for lunch.

For many years it was a happy gathering place where family

and friends could hang out, spend time with Neil, take a drive in

the cars, and even hold birthday celebrations.

It was here that Neil decided to write this book, inspired by

years of daily contact with the dream cars of his youth. Whether

he was planning a drive, making decisions on improvements,

both aesthetic and functional, or giving visitors a tour and

happily explaining the unique attributes of each car, this was his

happy place. He would often simply sit alone and look at his

cars which, as he told me several times, made him very, very

happy.

This was Neil's final piece of work, and he did not want this

book to be published until after his passing. When he asked me

to bring this book to fruition, I felt, and still feel so extremely

honored that he entrusted this to me. It has been a true labor of

love, and I am so proud to be able to share this beautiful book

with you.

HERE IS WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

Twenty-two years old, parts manager at my dad’s farm

equipment dealer in St. Catharines, Ontario, and barely

able to afford the payments on a two-thousand-dollar car.

(Mom bought the suit for me.) But what a car that was! The

Lotus was my second, following a purple MGB. It had originally

come in that garish Lotus orange that, well, might have been

“fashionable” (like purple!} — but I chose silver.

Twenty-two years old, parts manager at my dad’s farm

equipment dealer in St. Catharines, Ontario, and barely

able to afford the payments on a two-thousand-dollar car.

(Mom bought the suit for me.) But what a car that was! The

Lotus was my second, following a purple MGB. It had originally

come in that garish Lotus orange that, well, might have been

“fashionable” (like purple!} — but I chose silver.

Around 1977 I bought my first new car, a Mercedes 450 SL

convertible, black over tan. Unforgettable — that fall day when

the three of us came off the road and were driven to a garage

to pick up our new cars, including a 911 Targa for Geddy and a

Jaguar XJS for Alex. We actually raced on the streets of

Toronto! (Alex probably won.)

The next year the birth of daughter Selena demanded a

“family car,” so that became the 1979 Mercedes 6.9 sedan,

black over black. Just in summer weather, though — in

wintertime there were variations of International Scout and

Eagle, the pioneering four-by-four passenger cars.

I built a nice “car barn” beside the country house in

Beamsville, Ontario... and I polished them a lot. An MGTC and

an MGA also mixed in there, but still, I didn't know how to buy

an old car yet — I was ignorant of even the simple difference

between a “correct” example and the “driver” category. And I

had to learn that I did not feel comfortable in a red car —

because it was like wearing a nicely designed suit. But red.

Nice to look at, all right, but not to be looked at in.

In that climate of Southern Ontario, the cars couldn’t be

driven most of the year, except maybe a brief outing on local

roads if it was dry. It was no place to collect cars, really, at least

those you intended to drive — the roads were filthy with mud,

slush, and rain for at least half the year. I soon moved away

from cars and into motorcycles — maybe because I didn’t have

to care what they looked like. Audi quattros were my “winter

weapon” through that period, while during the summer I drove a

series of Porsche 911 convertibles. They were korrekt and

always reliable.

But twenty years later, when I found myself living in Southern

California, with famously good weather most of the time, it

worked.

DRIVING AS INSPIRATION

The title “Silver Surfers” for my car collection occurred to

me while driving the DB5 up and down the Pacific Coast

Highway. Because it felt right to me, I guess — the idea that I

was just one of the wave riders. I had moved from Toronto to

Los Angeles in 2000 cherchez la femme, and in search of

natural peace I often drove out that way and up into the Santa

Monica Mountains. Out past Malibu to Ventura County, I'd

weave along barren ridges of rock and vegetation, the ocean

always on one big side.

The title “Silver Surfers” for my car collection occurred to

me while driving the DB5 up and down the Pacific Coast

Highway. Because it felt right to me, I guess — the idea that I

was just one of the wave riders. I had moved from Toronto to

Los Angeles in 2000 cherchez la femme, and in search of

natural peace I often drove out that way and up into the Santa

Monica Mountains. Out past Malibu to Ventura County, I'd

weave along barren ridges of rock and vegetation, the ocean

always on one big side.

Some days would be misted by the marine layer, soft and

fine; other days the sun blared through a clear sky. Waves were

slow and gentle, or churned out a powerful, rolling rhythm — but

it was almost always pacific. People from less temperate

climates will know what it means to say it was always warm

enough.

For several years the DB5 was my only old car, so it got a lot

of use that way. Every year or two I would spend a month

commuting for pre-tour rehearsals to Drum Channel in Oxnard.

California — an hour up the coast from my home in Santa

Monica.

That was some kind of dream commute... and a perfect

opportunity to drive an old car. Later when I added the Jaguar,

Corvette, and Maserati Ghibli to that route, they never let me

down once, either, On other roads, yes, but I had them “sorted”

before I took them on the coastal commute.

As the older cars seemed to collect around me at this time,

they followed a natural path — cars built in the 1960s from

around the world. The Aston Martin DBS takes first place in this

order of display not only because I bought it first, but because it

was a car coming into the ‘60s carrying ‘50s technology. That

became my rule of thumb — displaying them by the development

of their thinking, as new ideas came into the fields of design

and engineering. And not until the '60s were done did the big

aerodynamic hammer smash down — downforce.

Just that one simple factor tells a huge tale. The fixation on streamlining that came alive in car design in the 30s to the ’70s finally brought us to downforce — well, nothing was ever the same. Just look at the "60s Aston Martin and the later DBs above—it’s

gotten all winged!

Just that one simple factor tells a huge tale. The fixation on streamlining that came alive in car design in the 30s to the ’70s finally brought us to downforce — well, nothing was ever the same. Just look at the "60s Aston Martin and the later DBs above—it’s

gotten all winged!

How strange that each of these seven old cars will cover the road at 150 miles per hour and more, but in no case should they! Upwards of 120 they create so much lift under the front end that it’s disturbing. (Yes, I know. Just had to try it — once.)

All those designs really needed was a slab of material across the front end to hold them down. But we didn’t know that yet...

It is interesting to compare a modern-retro interpretation of the best of ’60s cars, the 2000 BMW 78. I bought mine “nearly new” (3000 miles — a failed speculator) early on in the 2000s,

on my way back toward old cars with the intended “look.” These

days I keep it in my Quebec garage, with the 2015 Audi RS 7,

as the perfect two-season duo. The only noticeable variation in

the Z8 (Zed-Eight, when it’s in Canada) is the lower front end.

That's all it took to “stick ‘em down.” Amazing that it took so

long to apply aerodynamics to ground forces, really — but I

guess in the sky they weren't worried about “lift” so much?

No — on the ground they just didn’t think to measure it.

Looking back at the old photos of the red Daytona, in its day

the add-on front airdam (the lower chin) was absolutely frowned

at, and maybe sti/f would be. (It came installed.) Yet that was

about 1983, and it was made for the car by the North American

Racing Team (Ferrari's American branch). And it certainly

works. The final version of the Lamborghini Miura, the SV Jota,

also showed that crucial detail. Design had burst forward from

its previous dimness.

THE CARS

NEIL

end excerpt...

Silver Surfers: Sports Cars of the Sixties by Neil Peart