|

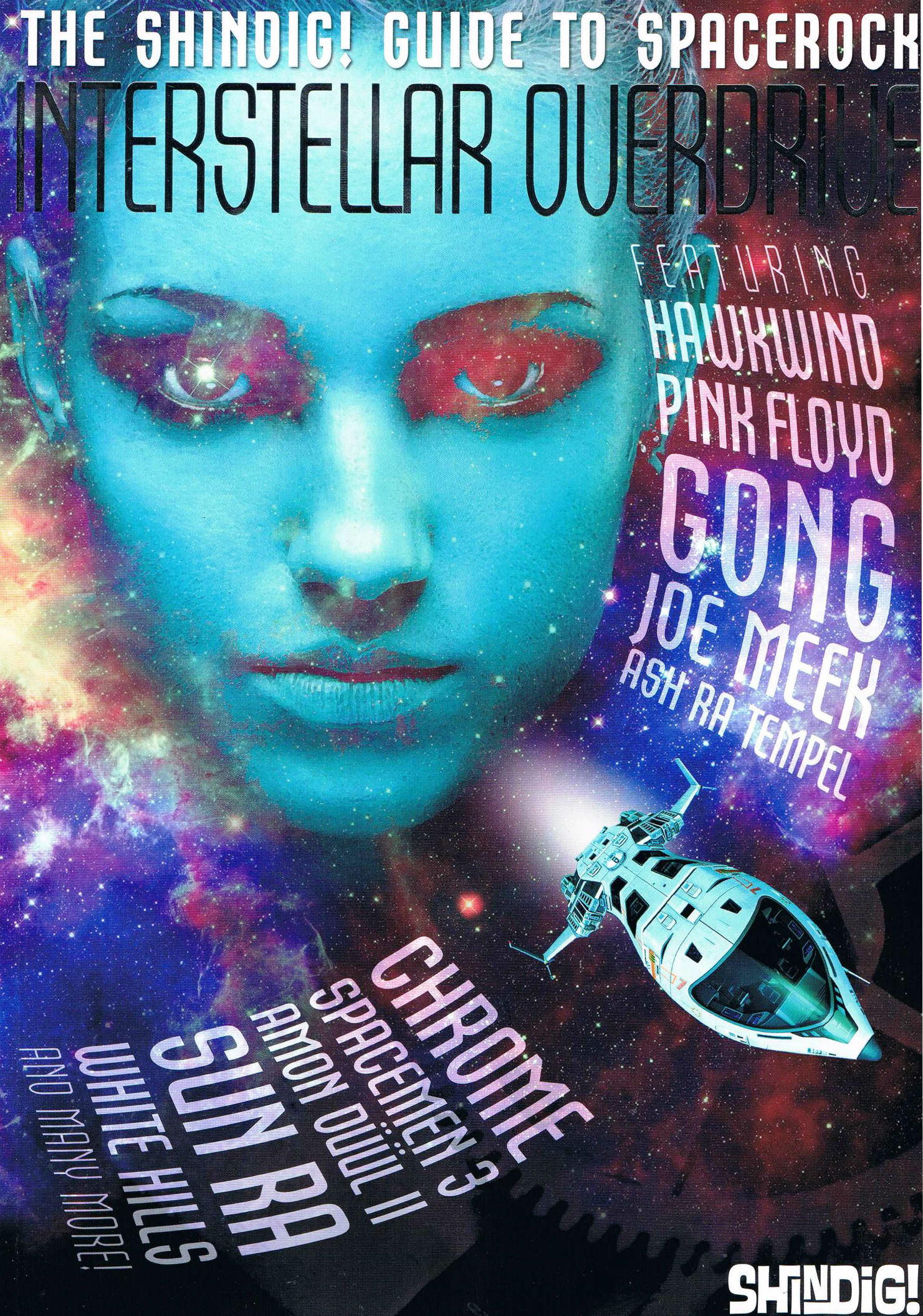

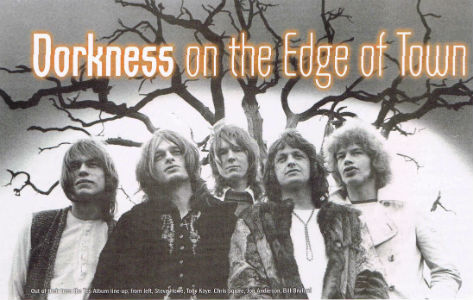

Dorkness on the Edge of Town Shindig! Magazine - Interstellar Overdrive Special January 2014 by Marco Rossi |

against the genre's heavyweights? MARCO ROSSI takes his protein pills and puts his helmet on to find out.

Click Any Image to Enlarge

There can be little doubt that Pink Floyd must take both the credit and the occasional shame of establishing the blueprint of the spacerock genre. With all due respect to the likes of Louis and Bebe Barron, Leon Theremin and, ah, The Spotnicks, I reckon that's a fair enough assessment - however furious a dissembling Roger Waters used to become if any earnest European journalists were gauche enough to reverently (and inadvisably) describe the Floyd's music as spacerock in his glowering presence. Thing is, quite apart from the substantial little tranche of Floyd song titles referencing the cosmos - or at least the upper atmosphere - in the "bang to rights" column, they spent an awfully long time musically evoking deep space, did they not? Just for starters, the bit in 'Interstellar Overdrive' where the drums stop is quite clearly the moment when a command module separates from a rocket and slowly recedes into A For Andromeda infinities. Patently, I could go on. And on.

Conversely, back in the day I always struggled to accept Hawkwind into the spacerock fraternity, for one simple reason: Stacia. I would strongly argue that the corybantic centre-stage dancing of a voluptuous naked woman ensured that the audience's thoughts remained resolutely earthbound, and in fact got no further into space than approximately 4ft off the ground. Besides which, the band's agrarian riffing was surely too Massey Ferguson by half to generate sufficient thrust for escaping earth gravity.

Conversely, back in the day I always struggled to accept Hawkwind into the spacerock fraternity, for one simple reason: Stacia. I would strongly argue that the corybantic centre-stage dancing of a voluptuous naked woman ensured that the audience's thoughts remained resolutely earthbound, and in fact got no further into space than approximately 4ft off the ground. Besides which, the band's agrarian riffing was surely too Massey Ferguson by half to generate sufficient thrust for escaping earth gravity.

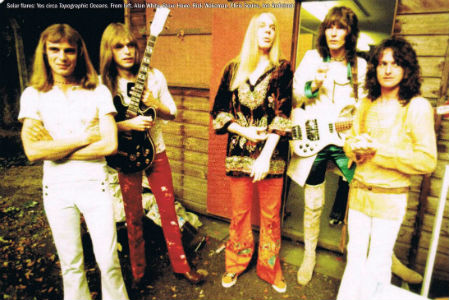

But what of bands such as Yes and Rush, whose respective orbits dragged them into the debate almost by default? Could such endearingly dorkish musos, beloved of specky suburban teenagers with band logos felt-tipped onto their jeans, ever be counted alongside dauntless bona-fide kosmische cosmonauts? Let's chew it over for a bit.

The first relatively direct intimation that Yes might harbour any ambitions whatsoever in this direction was signalled by Jon

Anderson's 'Astral Traveller' from the band's second album, '70's Time And A Word: even if the opening line "And in the ruins of the balloon" implies that the song's protagonist was closer in essence to Phileas Fogg (yeah, or Richard Branson) than Dan Dare. And in truth, apart from Anderson's disembodied vocal, piped through the whirling horns of a Leslie cabinet, the track sounds considerably less like the music of the spheres and far more like the tumultuously brilliant early Yes always did - belligerent, rattling and valvey, a kinetic cataclysm of growling, key-clicking Hammond, warring Rickenbackers and an expertly-tuned top kit. The song's cheerily industrious midsection, meanwhile, doesn't evoke Saturn's rings so much as it does the three rings of a thriving circus, with dogs jumping through hoops, a grinning magician spinning Expo '70 souvenir plates and a showgirl being sawn into eighths.

Come the following year's The Yes Album, `Starship Trooper' looked on the face of it like a more overt attempt by the band to nail their colours to spacerock's comet tail: the title is derived from sci-fi seer Robert A Heinlein's '59 novel Starship Troopers after all. Now, it should come as little surprise that there are no discernible allusions to Heinlein's contentious, militaristic parable in Yes's lyrics here, which are pretty much the failsafe combination of peacenik new-age generalities, pick-'n'-mix spiritualism and impenetrable syllabic grouting that sustained them from note one. There's no comparison between Yes's sweet-natured, nebulously idealistic realm and the "jackboot utopianism" which some commentators, not least Hawkwind affiliate Michael Moorcock, detected in the Heinlein tome. But however you slice it, the glistening introductory riff in the Yes song is a gorgeous, sunny thing, undeniably pointing skywards: and the concluding subsection, `Wurm', at least gave guitarist Steve Howe a chance to use his spacey new flanger in anger.

Nine months after The Yes Album, the November '71 release of Fragile heralded the arrival of two key elements regarding Yes's relevance to the spacerock discussion. Firstly, speaking of keys, keyboardist du jour Rick Wakeman had entered the frame. His predecessor, the estimable Tony Kaye, had developed a profound fixation with The Band, whose root-and-branch folksiness was obviously at odds with Yes's Pythagorean constructs. Something had to give. Furthermore, Kaye's ambivalence towards synths when there were perfectly serviceable Hammonds and pianos on the premises effectively marked him out as a reactionary: a crude-oil-begrimed Sopwith Camel grease monkey next to Wakeman's emissary from the future, armed with a gleaming array of state-of-the-art bells and whistles.

Secondly and, arguably, most significantly in spacerock terms, Fragile was the first Yes album to feature cover artwork by Roger Dean. His organic, painstakingly-rendered tableaus reinforced the impression garnered by the more excitable/suggestible/stoned wingnuts among Yes's fan base that the band were azimuth-scanning visionaries, already looking to split this nowhere scene and colonise other, more Arcadian planets, embarking in a space fish-galleon much like the one depicted on Fragile's cover. Right there, when considering the incalculable number of spliffs that must have been skinned up on Dean's gatefold Yes sleeves over the years, we have lift-off.

For my money, Fragile's closing track - 'Heart Of The Sunrise' - actually represents the band's best shot at star-voyaging transcendence. That hurtling, inexorable riff, livid with tension-ratcheting inversions, suggests an imminent interplanetary burn-out. The nose cone is glowing, the gauges are boiling and rivets are popping off the superstructure. Wakeman 's oblique, gaseous Mellotron interludes are powdery nebulae glimpsed from the window/ porthole/gill - whichever one you might have on a space fish-galleon - and the contemplative verses are as still as dead airlocks. Of course, the lyrics seemingly bear about as much relevance to the title as plankton does to quantity surveying, and the title itself really ought to tip a shilling to the Floyd's 'Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun': but the overall effect is the clincher.

Other Yes men may beg to differ, naturally. What about '72's Close To the Edge, with one of Dean's most transgressive sleeve designs? (The mystical, watery plateau above the clouds inside the gatefold, pedants: not the mildewed-shed greens of the outer sleeve.) What about Tales Of Topographic Oceans, four of the most arcane, brow-knotting sides of vinyl this side of Stanley Unwin Belches Quantum Theory In Binary Code? What about Gates Of Bloody Delirium? Well, as any space cadet knows, Yes were grandiloquently referring to their own superabundant abilities as players in the title of Close To The Edge: and as far as spacerock is concerned, there's the proverbial rub. The Byzantine musicality of what they did in the years between '72 and '78 (at a push) rendered it impossible for me as a listener to cut the cord and drift among the asteroids, because I was always distracted by that poll-topping craftsmanship. Something like, say, 'Awaken' from '77's Going For The One - a gusher of ascension, boasting more shivering climaxes than a day-long mash-up of Ron Jeremy's money shots - may well qualify as a heavenly, awe-inspiring, quasi-religious experience, but that's a whole different kettle from spacerock in my book (the 1965 Eagle annual). To my mind, music which truly depicts the inconceivably vast weirdness of space requires a certain abstract quality, a chilly emotional neutrality - hell, some disconcerting noises, quasar pulses and Quatermass oscillations - to make it work, which is why less athletic players such as the Mk 1 Floyd and pre-Phaedra Tangerine Dream made such a fine fist of it. if you aren't capable of whipping out a jaw-dropping high-wire solo you have nothing whatsoever to lose, and that can be surprisingly empowering: so why not send your Binson Echorec into meltdown for half an hour?

The First Canadians in Space?

The First Canadians in Space?

Many of the same caveats that narrowed Yes's spacerock scope in my view are just as applicable to Rush, with more besides. Their heroic ensemble playing not only provokes a welter of air-guitar-air-drums-air-bass aerobathons among their fans - a winningly ludicrous, joyous sight which inevitably applies the airbrakes to any onlookers contemplating solemn space exploration — but also comes freighted with a decidedly grounded (and utterly redeeming) skein of self-deflating humour. Witness the band's onstage backline of rotisseries and launderette washing machines, or ask anyone who has seen — for example — the deftly-honed knockabout skits that form linking sequences in the Time Machine 2011 DVD: Rush patently owe a bigger debt to the Marx brothers than they do to the crew of Fireball XL5.

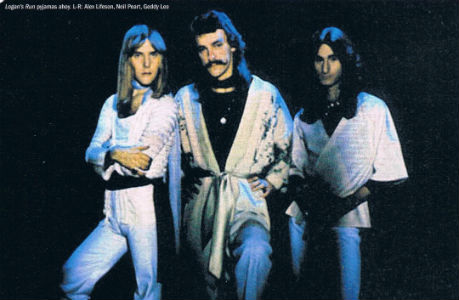

As far as I can hypothesise, Rush were somewhat bemused to be ushered to those plum seats at the spacerock table: perhaps they were wearing those white sateen Logan's Run pyjamas at the time. More plausibly, it's all 2112's fault. This shit-or-bust '76 concept album was famously the one that was either going to elevate the Canadian trio to enormodrome divinity or banish them to the outskirts of nowheresville, reduced to whittling souvenir caribou heads out of their own double-necked guitars in a trailer park. Fortuitously, fate eeny-meenied the former destiny: somehow, a cunningly allegorical suite about "a galaxy-wide war resulting in the union of all planets under the rule of the Red Star of the Solar Federation" struck a chord with hundreds of thousands of teenage dreamers in urgent need of a girlfriend.

Drummer Neil Peart's lyrics to the 20-minute title track famously (and infamously) owed a debt of gratitude to novelist/essayist Ayn Rand - not for the first time - and her theory of "objectivism". Now, speaking as someone who frowned through Rand's books The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged as a teenage dreamer in urgent need of a girlfriend, I can see how her central tenets of libertarianism and individual rights fed into 2112's man-against-the-machine narrative: but for the life and death of me never figure out how this led to the NME accusing Rush at the time of perpetrating fascism. This seems like a willfully arse-about-face misinterpretation: but then it's entirely possible that the teenage me missed some telling nuances in Rand's thicket of prose while I was squeezing my spots and basting my cheesecloth shirt in Hai Karate. I'm obviously going to have to read the sodding things again.

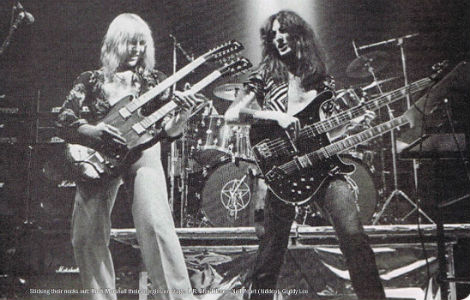

In any case, the point I'm laboriously trying to get to is that space-referencing lyrics don't automatically make something into spacerock: on their formative '70s albums, surely Rush were always meticulous artisans and methodical fantasists as opposed to precipitate space biscuits? I have absolutely no problem with defining the bleeping onset of the 2112 overture as spacerock in excelsis, but when Peart, guitarist Alex Lifeson and bassist Geddy Lee crack into the staccato introductory riff, it's more like a Yes/Jethro Tull summit meeting with everyone trying to stand on one leg. When they subsequently break into a canter, it sounds as bright and encouraging as so many of the most defining Rush centrepieces always do ('Xanadu', 'Limelight', 'La Villa Strangiato'). By the time they throw in the most notorious nod to Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture since The Move's 'Night Of Fear', you're more likely to be chuckling and making devil horns with your fingers than you are to be executing a spacewalk.

Elsewhere on the 2112 album, there's also the small matter of 'The Twilight Zone', a venture into the fourth dimension promisingly based upon two episodes from Rod Serling's reliably quixotic, inquisitive '505/'605 TV series of the same name (Will The Real Martian Please Stand Up and Stopover In A Quiet Town). However, this ends up being a markedly pleasant acoustic shuffle as opposed to the abstruse void-fest implied by that emotive title. Close, but no cigar-shaped space projectile.

Elsewhere on the 2112 album, there's also the small matter of 'The Twilight Zone', a venture into the fourth dimension promisingly based upon two episodes from Rod Serling's reliably quixotic, inquisitive '505/'605 TV series of the same name (Will The Real Martian Please Stand Up and Stopover In A Quiet Town). However, this ends up being a markedly pleasant acoustic shuffle as opposed to the abstruse void-fest implied by that emotive title. Close, but no cigar-shaped space projectile.

The other main contender for spacerock significance in the Rush canon would have to be 'Cygnus X-1', which they split into two "books", God bless and preserve them, over the space of two albums: '77's A Farewell To Kings and '78's Hemispheres. Cygnus X-1 is a black hole, see, discovered in '64 — by which time it was already five million years old. Rush used it as the basis for a hefty treatise on the conflicting imperatives of head and heart. An astral traveller rather carelessly gets sucked into the black hole in question during 'Book 1: The Voyage' and pops out in Olympus (if I didn't abhor the phrase so much, I'd now say "as you do") during 'Book 11: Hemispheres'. Apollo and Dionysus get roped into the argument, not unreasonably, and our unstintingly equivocal galaxy explorer emerges as a whole new deity - Cygnus, God of Balance.

On the face of it, this admittedly reads like so much eyewash: but there has always been an intellectual rigour to Peart's lyrics, a thoughtful layering of overt and covert meanings, that renders them among the most fully realised of their much-maligned kind. Mind you, it still doesn't sound much like spacerock to me, once you've progressed beyond the musique concrete intro and synthesized voiceover in 'Book 1': and it should perhaps be noted that the band's lyrical concerns tended more towards the temporal as their songs became tighter and their ties became thinner in the '80s. Odd aberrations still poked through on occasion - the 'Hyperspace' subsection in 'Natural Science' from Permanent Waves for instance, or 'Countdown' from Signals, which gushingly reimagines the Space Shuttle as a veritable love object - but by and large, metaphorical meditations on the human condition edged out the flightier fancies.

To summarise, then (ragged cheers): even if I've yet to be convinced that Rush and Yes comfortably fit into the spacerock pigeonhole - or indeed black hole - it doesn't diminish what either band achieved. As frontline prog progenitors, what they did have in common with spacerockers was the restless, implacable urge to forge ahead, to explore, to discover. Ok, to boldly go. Rush and Yes were also on a quest: and who's to say that the compulsion to ascertain what's on the far side of your own musical abilities is any less noble than a longing to express the glorious, unknowable indifference of the universe?