|

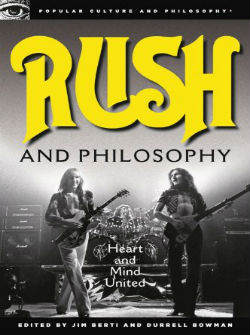

Heart and Mind United Edited by Jim Berti and Durrell Bowman April 2011 (Preview) |

The progressive/hard rock band Rush has never been as popular as it is now. A documentary film about the band, Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage, which was released in the summer of 2010 has been universally well received. They had a cameo in the movie I Love You Man. Their seven-part song “2112” was included in a version of “Guitar Hero” released in 2010. The group even appeared on The Colbert Report.

Even legendary trios such as Led Zeppelin, Cream, and The Police don’t enjoy the commitment and devotion that Rush’s fans lavish on Alex, Geddy, and Neil. In part, this is because Rush is equally devoted to its fans. Since their first album in 1974, they have released 18 additional albums and toured the world following nearly every release. Today, when other 70s-bands have either broken up or become nostalgia acts, Rush continues to sell out arenas and amphitheatres and sell albums—to date Rush has sold over 40 million albums. They are ranked fourth after The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and Aerosmith for the most consecutive gold or platinum albums by a rock band.

Rush’s success is also due to its intellectual approach to music and sound. The concept album 2112 made Rush a world-class band and cemented its reputation as the thinking-person’s progressive rock trio. Rush’s interest in political philosophy, mind-control, the nature of free-will, of individuality, and our relationship to machines makes Rush a band that matters and which speaks to its fans directly and honestly like no other. Lyricist Niel Peart has even built a following by writing books, both about his motorcycle travels and about the tragic death of his daughter, which have only furthered the respect Rush’s fans have for (arguably) rock’s greatest drummer and lyricist.

Fiercely independent of trends, Rush has maintained a clear mission and purpose throughout their career. With the unique “Rush sound,” the band has been able to blend thought-provoking lyrics and music for almost four decades. The Rush style of music can trigger the unusual combination of air-drumming, air-guitar, singing along, and fist-pumping, just as much as it can thoughtful reflection and deep thinking, making Rush “The Thinking Man’s Band.”

Rush and Philosophy does not set out to sway the public’s opinion, nor is it an awkward gushing of how much the authors love Rush. Rush and Philosophy is a fascinating look at the music and lyrics of the band, setting out to address thought-provoking questions. For example, elements of philosophical thinking from the likes of Jean Paul-Sartre, Ayn Rand, and Plato can be found in Peart’s lyrics; does this make Peart a disciple of philosophy? In what ways has technology influenced the band through the decades? Can there be too much technology for a power-trio? Can listening to Rush’s music and lyrics lead listeners to think more clearly, responsibly, and happily? Is the band’s music a “pleasant distraction” from the singing of Geddy Lee? In what ways is Rush Canadian? How can a band that has been referred to as “right-wing” also criticize big government, religion, and imperialism?

Rush and Philosophy is written by an assortment of philosophers and scholars with eclectic and diverse backgrounds who love Rush’s music and who “get” the meaning and importance of it. They discuss Rush with the enthusiasm of fan. The book will be a must-read for the many fans who have long known that Rush deserves as much respect as the ideas, concepts, and puzzles about human existence they write and compose music about.

Open Court Publishing

CONTENTS

Introduction - Listen to My Music, and Hear What It Can Do

PART I - To the Margin of Error

Chapter 1 - Yesterday’s Tom Sawyers

Chapter 2 - Barenaked Death Metal Trip-Hopping on Industrial Strings

Chapter 3 - The Groove of Rush’s Complex Rhythms

Chapter 4 - Nailed It!

Chapter 5 - Can’t Hear the Forest for the Cave?

PART II - The Ebb and Flow of Tidal Fortune

Chapter 6 - Rush’s Revolutionary Psychology

Chapter 7 - Rush’s Metaphysical Revenge

Chapter 8 - Ghost Riding the Razor’s Edge

Chapter 9 - Honey on the Rim of the Larger Bowl

Chapter 10 - How We Value a Gift Beyond Price

Chapter 11 - Free Wills and Sweet Miracles

PART III - I Want to Look Around Me Now

Chapter 12 - A Heart and Mind United

Chapter 13 - More than They Bargained For

Chapter 14 - Contre Nous

Chapter 15 - The Inner and Outer Worlds of Minds and Selves

Chapter 16 - Cruising in Prime Time

PART IV - The Blacksmith and the Artist

Chapter 17 - What Can This Strange Device Be?

Chapter 18 - Enlightened Thoughts, Mystic Words

Chapter 19 - Rush’s Libertarianism Never Fit the Plan

Chapter 20 - Neil Peart versus Ayn Rand

Chapter 21 - How Is Rush Canadian?

Co-Produced By

Index

- Yesterday’s Tom Sawyers -

by RANDALL E. AUXIER

It was October of 1977, the Farewell to Kings Tour, and Rush was coming to Memphis. They went

almost everywhere but Parsippany on that endless tour—I mean, they made it to Dothan, Alabama,

and Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, where they split the bill with Tom Petty (now there’s a case of

musical cognitive dissonance). I hadn’t really heard of Rush. Like an idiot, I was still listening to the

last band my friend “Brice” got me into three years before, Led Zeppelin (and I’m still listening), and

in the week of which I will speak, I also had out my old Lynyrd Skynyrd albums, mourning the sky

plunge of Ronnie van Zandt and friends. (“Old” is a highly relative thing; my favorite Skynyrd albums

were simply ancient, you know—I got them when I was fourteen, two years before.)

Rush’s 2112 had caught the ears of all the teen-aficionados-ofwhat’s-next, and I certainly wasn’t

one such. But way across town, some thirty miles from my digs in a humble part of town, my friend

from elementary school, “Brice Kennedy,” was experiencing a serious meltdown. Brice Kennedy is

not his real name, which is being withheld because, well, he’s still out there, and he’s now a

Republican. Back then he wasn’t, although I now understand why he made me play all these board

games built around financial transactions, like Monopoly, and Masterpiece, and Stocks and Bonds—

he taught me what leverage was and then amortized my ass, but good. Anyway, he was the guy, and

every school had one, who really knew music, sort of what Chuck Klosterman must’ve been like in

high school. This attention to the details and fringes of music actually makes you geeky at that age (or,

in Klosterman’s case, geeky, narcissistic, annoying and self-indulgent, even if your taste in music is

unmatched).

The meltdown came to this: Brice had somehow scored second row, center section seats for the

Rush concert, and his very strict (and sometimes arbitrary) parents had just denied him permission to

go to said concert. They had their reasons, I’m sure. Those were the glorious days when the rule was:

the lights go down then the people light up. Even Brice’s parents had caught on to that little feature of

the youth culture. And unlike parents today, they could truthfully report they never themselves inhaled.

It’s embarrassing in any generation to still be asking your parents’ permission to go somewhere at

sixteen. I mean you’re just getting to the point that they sort of couldn’t stop you, except with the “I

pay the bills argument,” an idle threat which invites one’s own flesh and blood to contemplate

homelessness and is oh-so-easy to see through. But old habits die hard, and at sixteen you don’t quite

want to test those waters, at least if they’ve been fairly good to you. I wouldn’t say Brice’s parents

had been exactly “good to him,” yanking him as they did from the public school system when bussing

started and sending him to a very expensive prep school for boys. I mean, no girls, and rich assholes

establishing their pecking order with no girls to make them feel insecure about it, and did I mention

no girls? Frankly, I’d rather go to military school to be made into a man, and I think no jury of

sixteen-year-old boys would have convicted Brice of failing to honor his mother and father if he’d

told them to piss off. But Brice wasn’t quite to the point of openly defying the elders. Rather,

unbeknownst to them, he had, of necessity, become Tom-Sawyer-devious.

Philosophical Moments

Among fans, the themes and lyrical motifs in Rush’s important early songs, especially on 2112, are

widely recognized as being driven by philosophical concepts. Unhappily, the “philosophy” they are

supposedly advancing is the ideological individualism and “objectivism” of the pseudo-philosopher

Ayn Rand. Now, before you go either grinning in approval or snarling at me, I don’t call Rand a

pseudo-philosopher as an insult. Like absolutely everybody else in the world, Rand had some

philosophical ideas, and, being an aspiring novelist, those ideas informed her narratives and

characters in thematic ways. But even a Hardy Boys mystery has that much philosophy (and as I now

consider it, I’m pretty sure the Hardy Boys probably grew up to be Republicans too). I doubt it

initially dawned on Rand to try to be a philosopher—up until people began to respond favorably to

the philosophical aspects of her writing.

It’s sort of like what happens when several people tell you independently “I like that hat on you.”

You’re likely not only to wear it more, but to start buying hats based on their proximity to the one

people like. It’s only human. But that doesn’t make you so much as a hatter, let alone a maven of

fashion. If you then present yourself as hatter or maven, and ignorant people believe you, don’t be

surprised when the hatters are pissed and the fashion mavens are laughing. (This, by the way is called

an “argument from analogy,” and one difference between a follower of Rand and a philosopher is that

philosophers both know and admit that analogies settle nothing, and also know when they are relying

on one. Rand’s entire philosophy is built on questionable analogies, and her following consists of

people who either don’t know that or won’t admit it.)

All people have philosophical moments, but most people don’t credit their own philosophical

thoughts. They forget them quickly and certainly don’t do anything about them. What is there to do

about having a philosophical thought? Well, plenty, but like anything else, you’ll have to practice, and

learn, and read, and work at it to do anything very good with such ideas. Now some people have lots

of philosophical moments, but not all of them become philosophers. Rand had a handful of

philosophical ideas that she visited over and over, none of them original (but that isn’t important in

philosophy), and she also learned in a superficial way to stitch them together into the rudimentary

semblance of a “philosophy.” In this respect, Rand was like Mark Twain, George Orwell, Emile

Zola, and even Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (who were operating on a higher plane), in that she had a lot

of such moments, credited them, and put them to work in a more or less co-ordinated way. She was by

a long stretch, as a writer and thinker, the inferior of all of those mentioned above, but in terms of

successfully combining philosophical ideas with fiction writing, she was better than the average bear.

No one likes Rand better than tweenage males who think themselves misunderstood geniuses. It’s a

shame that people have hung the Rand-albatross on Neil Peart, just because he read some Rand at an

impressionable age. It’s especially unfortunate since, unlike the hordes of other infantile, selfregarding

tweenage males so affected, Neil actually was a misunderstood genius. The hordes don’t

usually have much to show for their supposed genius, except a few, like Alan Greenspan, who have

more to apologize for than to prove their pretensions of genius. It is far better to have a modest selfestimation

and exceed it than to have a grandiose one and make others pay for the deficit.

My point is that when you look at Neil’s lyrics from that time period (part of the proof of his genius

is that he rather quickly outgrew all of this), what are you looking at? How is it that the lyrics and the

music from Rush’s “literary era” combine to make something that has, well, philosophical value,

even if it isn’t quite “philosophy”? Rush’s music is way, way better and more valuable as a cultural

contribution than anything Rand ever managed, in my opinion. I do think that there’s something in that

literary era of Rush that opens minds and that elevates the fans to places, good and worthy places,

they might not otherwise go.

Halloween Traditions, or, Are You Down with What You’re Up For?

The concert was scheduled for an inconvenient Sunday night, October 30th, downtown at Dixon-

Myers Hall, which was where the Memphis Symphony Orchestra performed at the time (hell, maybe

they still do). This was a concert hall, not a coliseum or arena. It promised incredible sound and

proximity. UFO and Max Webster both opened. That was going to make it a late night. I have no

memory of Max Webster and only the vaguest memory of UFO, that the lead singer, in mascara and

bright green pants, spit a lot as he vocalized and we were in the danger zone.

Maybe you’ve got a similar experience in your history, but Brice and I were finding less and less

to talk about after he moved to the rich side of town. As usual, friendship had been built on dozens of

common activities—sports, playing board games, collecting football cards, and especially music, as I

struggled to keep up with his ever expanding taste for progressive rock. To this day my album

collection (yes, I still have it—hope you kept yours too) bears Brice’s stamp. I felt sort of like a

musical contrail behind his Lear jet. But now I was more like Roger Waters, finding all the talk about

cars and money and rich people stuff a little off-putting.

Yet, since he moved, Brice and I had sort of started spending Halloween together. Two years

before Rush, he came to my house for a sleepover (and neighborhood marauding), one year before

Rush, I went to his neighborhood for the same. I don’t think we were actually planning to make it a

tradition, and I had already become, I think, something of a wrong-side-of-the-tracks embarrassment

for him in his new social circles, but then came those amazing tickets and his parents’ unbearable

denial of concert privileges.

Now yesterday’s Tom Sawyer was a modern-day warrior, and his mind was not for rent. So it

occurred to Brice that there might be a way, just maybe, to get to that concert after all. His folks

would surely believe that he was at my house for the now annual Halloween exchange, and since

Halloween was on an unworkable Monday, well, we’d just have to do our annual get-together on

Sunday (concert day). It probably crossed Brice’s mind to try the whole plan without calling me at

all, since another friend, let’s call him “Jim” (whose emerging worldly values were closer to

Brice’s), was already promised the second seat. But Brice believed in hedging his bets, and Jim

would just have to understand.

So Brice called me with the offer of a seat in exchange for, well, a willingness to join a conspiracy

(displacing Jim, who eventually ended up further back in the crowd, with a one-off ticket of some

kind). Now I’m no one’s Huckleberry friend, but I was up for this. Brice proposed to make a

weekend of it: Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, and this was intended to throw his folks off the trail, I

believe. And I was down with that. But there was a problem. My parents would be out of town Friday

and Saturday, and while they would willingly leave me for a weekend, no way would they leave

someone else’s kid, for whom they’d be responsible, etc., and no way would Brice’s folks let him

come to my house with the folks out of town . . . blah, blah, blah.

But I’ll bet you’ve already figured out what we told them. You’ve seen Risky Business. This would

be like that, minus Rebecca De Mornay, plus Brice Kennedy, minus Chicago, plus Memphis, minus

Bob Seger, plus Geddy Lee. It’s funny how parents’ perceptions run. My folks thought Brice was

probably a good influence on me, and his folks suspected I was a bad influence on him, when the truth

was exactly the opposite. Parents, if you are reading this, be chastened, be very chastened. You really

don’t know. Remember your own youth and tremble.

Lyrical Motifs

It has crossed your mind many times that song lyrics are not something you usually grasp the first time

you hear them. There are exceptions to this, of course—especially funny songs and story songs, where

the music is just there for effect and the whole point is the words. You can recognize such songs

almost immediately and then you sort of quickly decide whether you want to follow along or just tune

it out. That quick decision process is a relatively recent phenomenon in human history. Music is so

ubiquitous in our culture (God, I love having an excuse to use words like “ubiquitous”—I once

managed to get antidisestablishmentarianism into an article, and have now managed it again, except

that the last time it was legit and here it’s utterly gratuitous and annoying), where was I?

Oh yeah, the ubiquity of music in our culture makes it easy to forget that not very long ago, music

was a pretty special thing, not heard everywhere and anytime, but rather planned for, hoped for,

anticipated, relished. Real instruments were expensive and actual musicians relatively sparse. The

presence of music a hundred years ago rendered people rapt or ecstatic, or both in turns. It still has

that effect on traditional peoples whose ears aren’t ruined by the noise of modernity. In the days of

yore, you wouldn’t have decided whether to follow a story song. Rather, your body would grow still,

unbidden, and everything but the ear, and its peculiar power of focus, would simply fall into the

background.

You know it’s hard work to follow lyrics, and the music has to be arranged to create the right sonic

space for lyrics to punch through to the surface in perfect clarity. One thing that has to be pulled way

back, almost to silence, is the bass. The rumbling in those sonic ranges created by bass cancels all

clarity, takes the fine point off of enunciation, and it doesn’t take much bass to prevent people from

understanding the words entirely. On the other hand, when the bass ranges are prominent, it has the

effect of blending and melting all the other ranges together; bass can unify the music and weld the

percussive to the melodic.

The bass in Rush’s typical music is actually mixed loud, but along with the kick drum, it is

equalized thin to minimize this “cancellation effect” on the clarity of vocals and other instruments, but

still you aren’t going to get all the words in a Rush song. In fact, even with special attention and

cranking up the stereo at home, you’ll never understand them all until you read them somewhere.

Rather, what happens is that when the music pulls back for a dramatic moment, you’ll pick up a few

words, usually the repeated ones, and then the music will swell and take the rest away from you. Go

ahead, sing with me: “The world is, the world is love and light hmmm, hmmm . . . . Today’s Tom

Sawyer he gets high on you, hmmm hmm, hmmm, he gets by on you.” I know you’re with me.

Resistance Is Futile

This thing I just described actually has a name. The philosopher Susanne Langer (1895–1985) calls it

“the principle of assimilation.” Her claim is that wherever two or more fundamental art forms are

mixed (in this case music and poetry), one of them must assimilate the other to itself. For example,

where painting or sculpture is used to decorate a building, they would be assimilated to the art of

interior design, or, if the sculpture is outside, to architecture. Most painting and sculpture really is

just decoration, after all. An extreme case of this tension between art forms and assimilation is Frank

Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum building in New York, which assimilates interior design to

architecture, and then ingeniously assimilates even the greatest painting and sculpture into simple

decoration for his architecture. This is what Wright intended. That pisses off the interior designers

and painters and sculptors, of course, but to the architects it seems about right.

On the other hand, if you visit the Academia in Florence (where Michelangelo’s David is on

display), you will see an entire architectural edifice assimilated to the purpose of showcasing

Michelangelo’s sculptural works, especially his David, which was originally commissioned to stand

outside at the entrance of a government building, assimilated to the art of architecture or urban design,

but was later deemed by a later generation to be too good for that pedestrian function and made into

its own raison d’être. Does this “assimilation principle” hold true in every case? That’s a long

argument we can have some other time, but there are certainly many examples of it. It is clear that

differing art forms are constantly in tension when combined. Some art forms, like film, are ravenous

in their appetite for assimilating other art forms to their own primary structures. Film gobbles up

drama, acting, photography, painting, writing, music, interior design, urban design, architecture, and

more, turning them all into filmatic effects.

In music where words are being employed, there is a tension between poetry and pure music. In the

singer-songwriter genre, generally the music just supports the poetry. With the music of Rush the

lyrics are assimilated to the music, most of the time. “The Trees” and “Closer to the Heart” are

exceptions, and there are some others, but for the most part let’s just say you are not being encouraged

to sing along. Rather, Geddy’s voice is being used as a somewhat shrill lead instrument and the lyrics

simply cause the aesthetic qualities of his voice to vary in interesting and pleasing ways. It doesn’t

matter very much what he is singing about; the point is what it feels like and sounds like to hear him

sing. You may know that Neil was writing the lyrics because neither Geddy nor Alex had any real

interest in doing so. Whether they had any talent for it I don’t know, but lyrical talent wasn’t really

needed, only lyrical competence. This band wasn’t going to be about lyrics, it was about music. So

Neil got the job by default.

Now Neil Peart is not exactly the possessor of a great literary pedigree, but one thing I have

noticed about songwriters of all sorts: nearly all of them are avid readers. They love words. I was

just reading the autobiography of Keith Richards, and one learns near the end that he owns a massive

library and is addicted to (among so many other things) British and Roman history. Keith Richards.

Next to him, Neil Peart looks like a Harvard professor. So Neil was always a reader, and he read this

and that, and found that he liked mythology, ancient history, and, unfortunately, in callow youth, before

he had time to read widely, also Ayn Rand. No one who reads widely, and who gets the benefit of

that reading, is likely to hold her in very high esteem for very long. Emotionally damaged people and

those who simply cannot grow up are the exceptions, but then, they don’t get the full benefit of their

reading, do they? And in this they follow their heroine.

By the time of Moving Pictures, three years and some months after my night out with Brice, Neil

was writing lyrics about what he really knew: his own experience. He still wasn’t much of a poet and

it still didn’t matter. As I write this, Rush is preparing for a 2011 tour in which they will be playing

the Moving Pictures track list in order, for its thirtieth anniversary. It’s their best album and they

know it. No Ayn Rand on that masterwork. Neil’s lyrics are so much less contrived and closer to the

heart even beginning with A Farewell to Kings, so the flirtation with objectivist ideas was pretty

brief.

But even on Moving Pictures, if you try it, I think you’ll see that the lyrics can’t withstand the test

of being pulled from the music and examined as poetry. Some lyricists do pass that test—Robert Plant

writes in the same vein as Neil, for example, but is a much better poet; and Roger Waters is a bit like

Neil in his minimalist mood, but far better poetically. Still, even the best lyricists have a hard time

being taken seriously as poets because they often try to rhyme things, which just isn’t hip in poetry

these days. And thinking of Plant and Waters as other progressive rock lyricists, it is interesting that

in Zeppelin, the lyrics are almost always assimilated to the music, while with Pink Floyd, most often

the lyrics dominate the music whenever they are present. There isn’t a single formula here, but a

dynamic tension between two art forms.

It’s natural for these musicians to put in the audible foreground whatever is artistically best at any

given moment. When you’ve written lyrics as good as “Stairway to Heaven” or “Comfortably Numb,”

you don’t drown that out with bass. When everything in a piece is outstanding—music, lyrics, melody,

groove, tonal textures of the voice and guitars—well, in that situation, something is going to have to

be sacrificed to the whole. One of the most difficult moments in the production of a recording is the

moment when a musician has hit a riff that is so amazing on its own but it distracts the ear from some

other musical element that is more necessary to the whole. Such a riff has to be left out (or, as we

sometimes can do these days, moved to another place in the recording). It is tragic, but it happens

constantly in the art of recording. Live performance presents similar dilemmas, and the visual

presentation just complicates matters more.

Returning to the issue of assimilation of lyrics to music, as Rush favors, it creates a lower standard

of poetry needed, and that’s just fine. To provide another analogy: if you’re part of the crew building

the Notre Dame Cathedral and your boss says “sculpt me a Madonna for the roof,” you don’t need or

want a Michelangelo for that spot. It would be a waste to put in that kind of time and detail for

something no one ever sees up close. You want something that feels right from a couple hundred feet

below, and while you can’t afford to hire a sculptor who sucks, you do want one who understands

that this is about the building, not his statue, and who sculpts accordingly. Rush’s music is a veritable

Notre Dame of both living and processed sound, and it just isn’t about the lyrics, at least not very

much.

J-Wags, or, Are You Down with What You’re Up For?

The plan for Friday night (Rush, T-minus forty-eight hours and counting) was in Brice’s hands. We

were staying at my house, of course, while his folks believed my folks were home and my folks

believed I was at Brice’s house (and my sister was also gone somewhere that weekend, I don’t

remember where, but her absence becomes relevant at T-minus twenty-four hours). Brice actually

knew of a bar where they wouldn’t ask for our ID’s (drinking age was eighteen back then). This is

one reason to keep old friends even when you have little left in common; you might discover new uses

for each other. A bar? That was way beyond my ken. I didn’t think of myself as an innocent (I was,

sort of, but I didn’t like to think about it), but I had never been in a bar, and I certainly hadn’t heard of

this place called “J-Wags Lounge” in mid-town.

Anyone who knows Memphis is now saying “oh my God.” J-Wags, which is still operating, later

became a famous bar—a famous gay bar, that is. And here we were sixteen, straight, and clueless.

Now I want to be very clear that when it comes to gay bars, I am totally down with it, even if I’m not

up for it. Still, the worry is irrelevant because in 1977 J-Wags was just a neighborhood bar, not yet

having evolved into its future niche, and I now know how very ordinary it was.

I was instructed by Brice to wear a powder blue pinpoint Oxford shirt with a button-down collar

and khaki pants, and docksiders. This was all very important, I was told, because if you aren’t

dressed right, they might ask for your ID and then everything is ruined, right? Well, I was down with

doing as told to by those attempting to corrupt me, and I was pretty much up for some corruption. But I

had none of these clothes, so Brice lent me a shirt and I made do with that and Converse All-stars and

jeans. Thus shod and shirted, we set out.

Brice’s very cool and discreet older brother (he played a blue Stratocaster and was the prime

source of Brice’s cutting edge intelligence on what would soon be hip rock music among our younger

and more ignorant masses) took us to within a dozen blocks of J-Wags (we hadn’t told him the

destination, so he had deniability), and from there we hoofed it a pretty fair piece to J-Wags. Jim (of

the displaced ticket) had a car and was supposed to meet us there. And so he did. The concept of a

“designated driver” did not exist in 1977, but Jim was far more interested in getting stoned than

getting drunk, and a stoned driver, aged sixteen, is probably safer on the roads than the average sober

adult: our average speed home, probably thirty miles per hour.

The evening was passed, and you just won’t believe this, drinking actual beer in an actual bar and

playing pool with actual bar patrons. Doesn’t take much to thrill you at that age, does it? But the

anticipation of a whole weekend of such forbidden adventures, to be culminated in a Rush, well, it

was quite enough. Did I get drunk? Well, I had, like, four draft beers in three hours, with no resistance

to alcohol, at 5’ 7” and 115 lbs. You do the math. Did Brice? I actually don’t remember much. I woke

up in my own bed (alone). Jim must have somehow made it back to the rich side of town because he

wasn’t at my house Saturday morning, and somehow we were, and Jim was still alive Sunday night

when Rush came to town. He must have puttered back to the rich side. (I never saw Jim again after

that Sunday night, so I hope he turned out better than it looked like he would. But I’ll bet if he’s alive,

he’s a goddamn Republican.)

The Virtues of Virtual

Langer says that every basic art form accomplishes its “work” by taking some aspect of our actual

experience and making a semblance of that experience in a virtual space and/or time. Now, I’m

going to be honest with you, this is one honking big philosophical idea. It isn’t quite as honking big as

the idea of God, or freedom, or eternal life. (I’m not saying whether those ideas have any concrete

reality corresponding to them, only that at the very least they are ideas, and you can think about them.)

Those big boys would sort of be the Beethoven symphonies of philosophical ideas. This idea of

Langer’s is sort of more like a bitching Rush album of an idea. And hearing an idea like this just once

is akin to trying to take in 2112 and “get it” the first time through. It isn’t going to happen. But I’ve

spent about twenty years thinking on this idea of Langer’s, turning it over, trying to decide whether I

agree with it, so maybe I can save you some trouble. You decide. I still haven’t made up my mind, but

I think it’s a serious thought, sort of a way of cashing in on the claim that art imitates life, but richer.

So I’m going with it.

What does that idea mean? Basically she’s saying that the reason we recognize something as art

when we encounter it is that it reminds us of something in life that it recreates in a virtual way, as an

illusion. For example, painting, as an art form, makes a semblance in two dimensions of what it is

like to actually see things in three-dimensional space. Its “primary illusion,” then, is to reduce that

experience of seeing to two dimensions and to use pigments and geometrical tricks of the eye to

create the illusion. The “virtual space” is the space inside the painting. It sort of invites you to step

out of your actual space and into the virtual space of the painting, at least if it’s a good painting. This

is true even with abstract paintings: they exist in a virtual space, enclosed by a frame of the edges,

and if you stepped into the odd space occupied by an abstraction, I suppose you’d either become

abstract yourself of be in a pretty strange mixed space.

Sculpture, as an art form, recreates in a semblance the experience of the bodily traversal of the

lived space of action, the space of bodily movement. When you look at a sculpture, if it’s a good one,

it feels as if it has moved into the position it currently holds, and could very well move beyond it. To

compensate for the fact that the sculpture really doesn’t move, you move around it. The artwork exists

in a virtual space-time of a history of movements it never actually made, leading to its current pose,

and a virtual future of possible actions never to be enacted. The work invites you to furnish in your

imagination the movements leading up to the pose, and to finish those actions proceeding from its

frozen present. And you do that, in your imagination, whether you want to or not. The virtual space

and time of physical movement is the sculpture’s world, and it reminds you of your actual world of

movement when you see it.

But music, and pay close attention here, music creates the illusion of what it feels like living in

time’s flow . Nothing in music actually moves or lives, biologically, or has real feeling. Yet, music

feels to us as if it’s alive. Yes, the musicians are alive and they do move in actual time as they play

their instruments, but that is not “the music”: it’s just the physical activity in actual time that creates

the illusion of virtual time in the virtual movement of the music. Just as the brush strokes are not the

painting and the hammer strikes are not the sculpture; they create the illusion but are not themselves

illusory. This is pretty hard to understand, especially with music, but an example may help.

Imagine that Geddy is working up to singing a sustained high note; his vocal chords are tightening,

his throat is constricting, his breath is being forced through a smaller space, and sound issues forth. (I

hope he’s had a breath mint.) But nothing actually “goes up” when he hits a “high note.” There is

nothing in the physical activity of singing or playing an instrument that makes one note “higher”

(closer to the sky) than another note. Nor does anything actually move from “lower” to “higher” notes

in an “ascending” scale. Rather, one sequences individual tones in such a way as to produce the

illusion of rising; it feels like something is ascending when you hear it, even though nothing actually

rises. What’s really altered, in effect, as Geddy sings the high note, is the peaks and troughs of the

sound waves, propagating in actual space and time. The actual propagation is in actual time and

space, with the illusion of “higher” and “lower” pitch, is a part of the virtual character of music.

In the same way, music employs the actual passage of time as its physical basis for the sequencing

of varied sounds that provide us with an audible series of (oft repeating) virtual markers, called

tones, that remind us of the actual passage of time. The tones have individual duration, but they don’t

move. Tones are made of sound waves vibrating within a regular frequency of peaks and troughs

(with slight variation), but as tones, they offer only an illusion of stability for the duration during

which they exist. The sounds are actual, but treating them as tones is a virtualization of sound, a step

from what it actually is (sound) to its virtual temporal relations with other sounds that we will also

treat as tones. You recognize the difference between music and noise when you hear it, but you may

not realize how much of the difference between them lies in your willingness to treat the sounds as

tones. My folks were disinclined to treat my Rush albums as “music” way back when—it was an

awful noise they said. My mother, who was a voice teacher, was horrified by what Geddy Lee was

doing with his voice. Shrieking, she called it. They weren’t willing to virtualize what they were

hearing.

Now, if you think about it, you’ll agree that the tones do not make the actual time any more than the

sound does, and neither sound nor tone is one with the actual time; rather, unlike mere sounds, which

seem to be at the mercy of actual time, the tones use the actual time to create an illusion of movement

and repeatability within the relentless flow of our experience. The truth is that the flow of our

experience renders real actions unrepeatable. You cannot genuinely repeat any action, in the sense of

making one action identical to another action, because the time when any action was first performed

is now past, and unrecoverable. The best you can do in actual time is to perform an analogous act

and then pretend the time passage between the first and second enactment doesn’t matter. This is the

basis of virtualizing time, and music does it amazingly well.

Run That by Me One More Time

So we know that tones arranged in various combinations and series use time to create an illusion that

reminds us of our own flow of felt experiences: the music sounds like what it feels like to be alive, to

have a rhythmic heartbeat and a breathing pattern, to move our bodies up, down and all around, to be

obliged to anticipate the next moment and join it to the last moment by means of our present sensing

and feeling. But there are rules about how music has to do this in order to maintain the illusion.

Like so many things, the illusion music creates exists only between two extremes. Too much

automatic repetition in rhythms or tones kills the interest: the time is over-virtualized and does not

remind us of what it feels like to be alive, but sounds like a machine instead. The musical illusion is

broken and becomes mere sound. Too little repetition in the rhythmic or tonal scheme kills the

experience of the illusion of living (which does incorporate much repetition), and starts to seem like

actual, unrepeatable time. Music, the illusory semblance of our life of feeling, exists, then, between

these extremes; it is virtualized time.

Now I have to report something weird and kind of shocking. If Langer is right, the way humans

become conscious of actual time is by attending to the ways that music can use actual time to suspend

certain moments and contract others; the tension and release of energies in music points us to the

otherwise uninterrupted continuity of our flowing experience. Consciousness itself is a virtualization

of experience, and we become aware that we are conscious by way of music—not so much its

successful semblances, but at the points where semblance breaks down and actual time retakes us.

She actually believes that music is the key to our kind of consciousness (a self-reflective kind). If we

had nothing that was like time, but not time, how would we ever become aware of its passage? It’s a

fair question. So music is virtualized time, and the virtue of it is that it teaches us an awareness of

real time precisely because music just is illusory time.

Now the music of Rush (like all progressive rock) diverges from other rock music in using

repetition more sparsely. Most rock music is built on a virtual repetition of four beats, called 4/4

time, or “common time.” Whatever syncopation (that is, the violation of the evenness of the pulse

created by “early” attacks and the uneven sustaining of tones for rhythmic effect) regular rock music

contains is simple variation on the repeating four beats. It is there to punctuate the driving, regular and

repeating beat. There are thousands of regular grooves into which ordinary rock music can fall, but

all built on the matrix of common time.

Rush in particular and progressive rock in general is partly defined by its habit of hopping from

one time signature to another; the rhythms are driven and herded around in community by what seem

like almost mystical forces. The gods and demons subtract a beat here, add one there, squeeze two

into one, and take us just a bit beyond the predictable recurrent rhythms of ritual dance, or of our

living bodies. It feels sort of like being on a rollercoaster. It isn’t for everyone. In progressive rock,

the regularity of rhythmic order is sacrificed for the sake of a different way of virtualizing time.

Rhythmic patterns do exist and come back around, but they catch the listener unaware, and the

standard AB/AB/CB song structure of verses, choruses, and bridges is totally out the window. Even

the concept of a “song” isn’t always the basic musical unit. See Yes, Tales from Topographic

Oceans for some alternatives to the “song” concept. In this regard, progressive rock owes a lot to

jazz and even to classical music.

Interlude

So I’m writing this in a bar in Carbondale, Illinois, in December of 2010, and as I just typed that last

line, I look over, and the barkeep (a young blonde woman with a two-foot pony tail) is being accused

by the owner of playing him “like Tom Sawyer” by convincing him to shine the brass fittings on the

beer taps because she “isn’t sure how to do it right.” From this we learn two things. First, that I’m a

lot more familiar with bars at forty-nine than I was at sixteen, and second, that there is a fair case for

synchronicity.

The Sign of the Three

Something must be done to make sure the “center holds” when music is being played with little so

respect for the repeating latticework of a 4/4 beat. The center of Rush’s sound is and always has been

a little trick they use. So long as the bass line and the kick drum match exactly, and so long as the

actual tempo of the song (the number of beats per minute) does not vary too much, any amount of

syncopation (that early and late emphasizing of beats) and violation of time signatures can be

workable. So Neil and Geddy synch up the bass and kick drum and rehearse it as many times as

necessary, until it seems like that pinpoint precision happens on its own (which is also an illusion),

and then the more melodic elements can move whither they will without the whole thing feeling

confusing to the ear and body of a listener. It still feels like the passage of time, but with fits and

starts, just about where you want them. Classical and jazz composers also exploit our desire for more

temporal variation in our virtual time, which reminds us of the variations in the succession of our

actual feelings, but classical and jazz composers never, ever synch the rhythm of the bass and drum

movements as Neil and Geddy do.

I say this is a “trick” because all rock and blues and country musicians draw on the strategy of

using the kick drum to reinforce the movement of the bass, below the other instruments, but most of

them do it while respecting the regularity of four beats per measure. Of course there’s a lot more to

the Rush sound than the two characteristics I’ve mentioned: mixing the bass and kick drum hot with a

thin equalization, and synching them precisely. Rush is a three-piece band, and three-piece bands face

certain challenges that don’t emerge in larger bands. All three-piece bands have to find ways to keep

the sound full and fresh with limited hands and voices. There are dozens of ways to accomplish the

task.

It’s good to remember that having a lot of “empty space” (this is a metaphor of course) in a piece

of music is not always a problem. The early recordings of the Police show how three instruments can

do the same things Rush does, but in the spacious (as opposed to full) mode. Van Halen (when they

were three-piece) synched the bass and kick, kept the drums simple, fattened the bass sound and kept

it sustaining, and then let Eddie do the rest. The Who and Led Zeppelin never adopted the strategy of

precision synching of bass and kick drum except when it occasionally pleased them, while ZZ Top

just made up for its sparse instrumentation with volume and energy.

On the other hand, Rush isn’t exactly a three-piece band, since Geddy plays so many instruments

and sings at the same time, and Alex and Neil kick in the processed sounds as needed. But the music

has to be closely arranged so that the ear cannot detect when Geddy has moved off of the bass guitar

and is playing the bass line with his left hand on a keyboard or with his feet on the Taurus pedals,

which sometimes Alex also does. There are lots of pieces, but just three people, so the name is a bit

misleading. And there are three piece bands with four people (like The Who), so the point is, that’s a

lot of music for just a few fellows to be making.

To do all that Geddy does while singing the lead vocal is pretty freaking impressive. Lead singerbass

players are rare enough—count ’em, go ahead. Sting, Geddy, Paul McCartney, Roger Waters,

Richard Page, Eric Carmen, and who the hell else? There is a reason for this paucity. Unlike the

guitar and the drums, the bass generally plays against the melody, even in ordinary rock music, let

alone progressive rock. Singing while playing bass requires something quite beyond patting one’s

head while rubbing one’s stomach. To add in keyboards and pedals, and an occasional guitar, is

something more than human. It may look relaxed when you see Geddy do it, but that appearance is as

illusory as music itself. The boys have rehearsed this stuff into an automatism. They play it exactly the

same way every time, and they pretty well have to, to get it to work. They have been criticized for

this. I’ll take that up later.

Saturday Night’s Alright, or, Are You Really Up for What You’re Up For?

I don’t remember the day after J-Wags. I’m pretty sure me and Brice slept in and then probably ate

junk food and played board games, in which he probably whipped my ass, as always, and celebrated

said ass whipping insufferably. Unfortunately I can’t reveal everything about Saturday night (Rush, Tminus

twenty-four and counting), even at this late date. Too many of the principals are still alive and

haven’t given their permission (and they wouldn’t give it if I asked them—not for this night). Brice

probably wouldn’t mind, since on the scale of things he did later in life, this night probably doesn’t

even register a 1 on a scale of 1 to 10, (10 being the most unimaginable bad behavior). But on my

personal scale, this was about an 8.

Here’s what I can say. A lot of young people were celebrating Halloween that night. We actually

stayed home, at my folks’ (otherwise vacant) place. Brice had somehow procured for our enjoyment a

big bottle of Jack Daniels black label, maybe two, I don’t rightly remember. It was more than enough

in any case. By late afternoon the seals had been broken. We handed out candy to the kids as they

came by, rather more cheerily than would be usual. As the night wore on and various other activities

began to unfold, we were interrupted in our Bacchanal (which involved Rush albums at extreme

volume) by a knock on the front door. This led to a staggered scurrying and stowing of contraband,

forbidden literature, and other things that shan’t be mentioned.

It was two of my sister’s friends at the door—her friend “Carrie” and a fellow named “Bill,”

whom I barely knew from earlier days when he dated my sister instead of her (very attractive) friend.

The friendship survived his transfer of affection, and indeed, the switch led to a marriage of over

thirty years duration (and still going), with many kids. Must’ve been a decent trade. But in 1977

Carrie and Bill were all of seventeen. They were looking for my sister to go driving, or whatever.

But she was gone (I still don’t remember where). Yet, here we were, Brice and me, and as they

peeked in, it was pretty clear to them that, well, we had the “stuff.” And they had nothing in particular

to do. Let the Bacchanal resume.

What followed I just can’t quite describe, except that it probably isn’t as bad as you’re imagining

—and I didn’t lose my virginity until some time later, after I got my own car, so get your mind out of

that particular gutter. Another word to parents: if you want to hasten the loss of your children’s

virginity, by all means get them cars. This provides a mobile version of precisely what they lack,

which is a place to do what all of nature is encouraging them to do. Parents who won’t leave their

kids for Risky Business weekends, but who tell themselves it’s okay to get the kid a car, well, there is

no virtual space virtual enough to contain your self-deception. Do the right thing, I say. Get them pills

and condoms and tell them to go at it. They’re going to anyway. And of course, some won’t. It’s up to

them. If you do the right thing, it doesn’t matter about the car. None of this is philosophy. It’s just a

reminder of what you already know.

The only issue is whether you’re going to screw up their young minds with guilt. Abstinence my

ass. And what is with this puritanical culture? We declare wars on weaker peoples and massacre

them without reservation or conscience, and then depict it in all its gore in movies and news stories

for the public, and you (Republicans) have the audacity to tell me that sex is obscene? I’m sorry, but

fuck you. (This also is not a philosophical argument, it’s just a rant.) And while we’re interluding, I

notice that the Tom Sawyer routine of the barkeep worked for about five minutes before she ended up

polishing the brass by her lonesome. Tom Sawyer ain’t what he used to be. It seems that everyone is

on to his scam. But he’s become mean.

Aftermath: Not Down with What I Was Up For

No more about the proceedings that night, but when I woke up, after daylight, I was in better condition

than anyone else. Brice was hanging over the toilet in one bathroom, either unconscious or asleep

(who could tell?), and Bill was motionless in a pool of his own upchuckings in the other bathroom,

arms crossed over his chest in the attitude of a corpse. Carrie was passed out on the living room

couch (I didn’t look too close), and I was the only one who made it, part-way at least, to an actual

bed. I remember praying that the room would stop spinning. I woke up because, well, my urgent

choices were either to move Brice from his perch or to hazard stepping over Bill on my way to

transact a similar business in pink porcelain.

I swore to God in heaven (if there is one), as I gave up my insides to the sewer lines of Tennessee,

that never, never again would I become that intoxicated. So sincere was I in my repentance that I even

swore off all hard liquor then and there. I actually kept that pledge (it still tastes like cough medicine

to me). It was one of those deals where you’re still drunk when you wake up. I’m no goody good, but

I also don’t need to cut off a second finger to be absolutely certain I didn’t want to lose the first one.

If you’ve been sick-drunk and hung over like that more than once, well, all I have to say is you’re not

a very quick study.

My folks were to be home in the early afternoon, and one can’t take chances, so with much

groaning, general bleariness, and a bit of blaspheming, there was the gathering and dispatching of Bill

and Carrie, and then there was some serious cleaning, airing, and stowing to do. In our condition, it

took quite a while. My first hangover. Remember with me now, brothers and sisters, your first

hangover. Where were you? And how old? Yes, that’s it, let it all out. I’m here to heal your

memories. And Jesus protect us from the next hangover. And the one after that too. I now understand

the magical power of water and need Jesus less than before, but everybody needs a little Jesus now

and then, so I’m not abandoning the faith.

Processed Processes

Rush has been criticized for the full duration of its long career for mixing processed sounds with

sounds being played at that moment, on stage. It is actually pretty hard to tell sometimes what is being

played and what is being triggered by one of the band members that has been sampled or recorded or

sequenced in advance. But it is a fact of technology, up to the present (and this will change

eventually), that the processed sounds do not respond to the band’s musical activities; so the band has

to play along with the processed sounds.

That, friends and neighbors, is not easy to do. Not only must the processed sounds be triggered at

the precise moment needed, but the band has to be playing at the right tempo, or at least, they must

adapt to what they know the processed sounds will do. If a chord change has been sequenced, for

example, the band has to change chords with the sequence, and to know the precise moment. Only

mathematical precision on the part of the live players makes possible the mixing of processed sound

with live sound, at least if those sounds go beyond mere “sound effects.”

Armed with Langer’s ideas about virtual space and time, this endless debate takes on a new

dimension, so to speak. Given that music is already an illusion that reminds us of the flowing life of

our feelings, and given that this illusion is maintained within limits, we confront here the issue of

whether the processed sounds, which are illusions of illusions, or second order virtualizations, do or

don’t belong in live performance, and if so, whether they belong in the genre of progressive rock, and

in the music of Rush particularly. You are all aware of how Rush maintains its artistic integrity by

recording only what it can reproduce in live concerts without depending on extra musicians (and that

would include allowing sound engineers to trigger the processed sounds).

Clearly the band wants to maintain aesthetic and artistic integrity with regard to the limits of

processed sounds. They clearly realize that once you begin messing around with processed sounds,

there is always a danger that the first order virtualization will be swallowed by the second, and if that

were to happen, well, they might as well lip-synch the whole thing, and we won’t want to pay the

price for the tickets to see that. On the other hand, Rush made it clear from the outset that they

intended to use processed sounds to create their music. There is no chance that they can be accused of

shifting their ground, but as the technology has progressed, so has the sound (at least until they

decided to do just a bass, drums, and guitar thing with Vapor Trails in 2002).

If you think about this, from Langer’s point of view, all music is in some sense “processed sound,”

because the jump from actual sounds to virtual tones is, itself, a kind of processing. Indeed, that is the

crucial step because it is the move from actual to virtual time. Simply amplifying the music is another

step away from mere sound, but not as radical a step as from sound to music. So the issue is not really

whether the music is processed but how and how much. And this, like any other question in the

criticism of art, actually comes down to whether the art is good. The use of new technologies in any

art may or may not lead to better art. Usually the first attempts to accentuate an art form with a new

technology are quickly surpassed by later efforts, when the possibilities have been better understood

and mistakes have been made.

Once in a while some artist will really just know what to do with an innovation. For instance, the

1939 Wizard of Oz was the first feature-length film in “Technicolor,” which required quite a lot of

adaptation of sets and costumes so that the final film would look right—did you know that the ruby

slippers actually had to be orange in order to appear red in Technicolor? And so with Rush. Those

Moog Taurus pedals were only the beginning. Consistently Rush has been on the cutting edge of

technology and has also occasionally reminded fans and critics that they don’t really need all that

technological support to do what they do.

So I take myself to have settled a long standing question. Asking whether Rush should use all those

processors to make their music is closely akin to asking whether they should make any music. They

have communicated their aesthetic standards and the principles that maintain the integrity of their art

and their live performance. Everyone agrees that they can execute their music in concert, flawlessly.

The only appropriate question, then, is whether the music is good. To this question I will offer a short

answer. It is not all equally good, and there are times when the mathematical precision, from kickdrum/

bass matching up through processed sound, does kill the life in it. (In Langer’s terms, the music

sometimes becomes “discursive.”) But some of it is so very good that life bursts out of it, and here I

would mention my two favorite Rush songs. I hate to be predictable, but I never tire of “Tom Sawyer”

and “Limelight.” Great music. Even if I never can remember all the words.

Houston, We Have a Problem, or, What Goes Up Must Come Down

It was concert time. Brice and I had finished our Rush “homework,” and oh so much more. My

parents had returned on schedule, and of course, as far as they were concerned, we had arrived only

shortly before. I didn’t lie. We went to the store and arrived back at the house shortly before the

parents, which makes it technically true to say “we got here just a few minutes ago.” Parents, it is

good to be aware when your children have achieved “sophistication” with language. As with all

human achievements, this cuts both ways. If they’ve come to have a fair command of “nice

distinctions,” and if you think that niceness won’t be used in the service of narrow self-interest, then I

suggest you buy your kids cars and trust them to remain chaste and sober in the operation of those

machines. You’ll get what you deserve down the line.

I had never had such tickets, but sort of suffered through the first two bands, knowing nothing of

their music and being quite ready for the main event. And then, there they were, within a few feet,

doing, well, God knows what, in order to create all that sound. What did they play? Well, I wouldn’t

have been able to tell you exactly, except for the invention of the Internet and millions of people with

too much spare time. The list was:

• “Bastille Day”

• “Lakeside Park”

• “By-Tor and the Snow Dog” (abbreviated)

• “Xanadu”

• “A Farewell to Kings”

• “Something for Nothing”

• “Cygnus X-1”

• “Anthem” (Arrggh—but I had never heard of Ayn Rand back then and couldn’t understand the words anyway)

• “Closer to the Heart”

• “2112” (minus “Oracle”)

• “Working Man”

• “Fly by Night”

• “In the Mood”

• Drum Solo

• Encore: “Cinderella Man”

That’s how it went, I’m pretty sure. It’s a pretty awesome list. I’d pay a lot to see that show again,

and in fact, to have back the night (if not the morning that followed). Me and Brice and Jim and about

half a million other people saw that show in the course of that year. Maybe you’re one of them. I was

certainly hooked. Glorious show, definitely in the top ten I’ve ever seen.

But there was a problem. We arrived at my house euphoric from music (and the contact high we’d

managed), only to hear “Brice, call your parents.” I could tell by the tone that we were screwed.

There was something we hadn’t figured on. His mother called during the concert. My mother said,

“Oh, they’re at the concert.” I hadn’t lied to my parents about that part. I mean, they never would have

denied me permission to go to a concert, so why lie? Shit. Double shit. You can see how it unraveled

from there . . . “Oh, we thought Randy was over there” . . . “no, he wasn’t here, we thought they were

there” . . . “No, we went to Nashville” . . . Screwed. Totally.

But there was a difference. When you start listing and assessing the (known) crimes, you’ll see why

I wasn’t in nearly as much trouble as Brice. He disobeyed a direct order and created an elaborate

ruse to do it. I just did a Tom Sawyer meets Tom Cruise kind of thing. I was grounded for a week or

two, and still got my first car a month later as a Christmas present. And you know what cars lead to.

But in order to prevent themselves from killing him, Brice’s folks blamed the awfulness of it all on

my bad influence, and that was it for me and Brice. Never allowed to visit or communicate again. The

next time I saw him we were juniors in college, and well, we really had nothing in common by that

time. Except we still loved Zeppelin and Yes, and Rush, and our memories.