|

Every Album, Every Song by Richard James Released: December 20, 2024 (Preview) |

Rush. In their own words, ‘The World's Biggest Cult Band', started from humble beginnings: three suburban teenagers. Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee, and John Rutsey formed a Led Zeppelin-influenced trio, eventually scratching a living playing the bars and clubs of their native Toronto. A hard work ethic, no small amount of talent, and a slice of good fortune enabled their first, self-financed and distributed album to gain a foothold in the American market.

And then, on the eve of their first American tour, drummer Rutsey quit. Fortune smiled on them again when auditions for a replacement shed builder produced Neil Peart, who could not only drum like a demon but was adept at lyric writing. Sharing a love of the then emerging progressive rock scene, the trio embarked on crafting a series of albums from the ‘second' debut, Fly By Night, to the career-defining and best-selling masterpiece Moving Pictures; records which would secure them a permanent place in the rock hierarchy.

This book reviews all these albums up to Signals, their 1982 release, which saw the band embracing keyboard technology and severing their connections with long-time producer Terry Brown, the unofficial fourth member of the trio.

My thanks are due to the following people:

Mike Rawsthorne, for reading everything I write and agreeing with me most of the time; Alison James, for explaining the long words and reminding me why grammar is important; Dotty Trippier, for being my best guitar student and introducing me to the music of McFly.

CONTENTS

Enter Stage Left

Rush

Fly By Night

Caress Of Steel

2112

All The World’s A Stage

A Farewell To Kings

Different Stages — Disc 3 — 20 February 1978

Hemispheres

Permanent Waves

Moving Pictures

Exit — Stage Left

Signals

...To Be Continued

The Best Of Brown

ENTER STAGE LEFT...

Some school friendships last a lifetime. Bands formed in teenage years,

however, rarely last into adulthood. If they do, any form of success is unusual.

This puts Gershon Eliezer Weinrib and Aleksandar Zivojinovié in a unique

position. Add in, slightly later, Neil Ellwood Peart, and you have a highly

potent, exceptionally talented, progressive heavy rock trio, which would be

eventually awarded the Order of Canada and be included in the Rock ’n’ Roll

Hall of Fame. In short, Rush.

The trio would become musical heroes to a massive fan base with statistics

that may amaze those unfamiliar with their work. Over 43 million album

sales, promoted by over 2000 concerts; a five-decade career; 20 studio and 11

live albums, and some of the best rock music ever recorded, is an unmatched

record for a band which, with one early exception, maintained the same line

up throughout their career. In terms of album sales alone, Rush are only

bested by The Beatles (four members) and The Rolling Stones (five members).

So, from a mathematical standpoint alone, they offer the highest ratio of

talent per player to quantifiable success. Numbers and statistics really matter

to some people. For the trio from Ontario, not so much. They just wanted to

play the music they wanted to play, their way or not at all. It was only and

always the music that mattered. Everything that followed (fame, fortune and

occasional despair) was merely a consequence of doing what they were best

at, a fact that many legions of fans across the globe can attest to.

The trio would become musical heroes to a massive fan base with statistics

that may amaze those unfamiliar with their work. Over 43 million album

sales, promoted by over 2000 concerts; a five-decade career; 20 studio and 11

live albums, and some of the best rock music ever recorded, is an unmatched

record for a band which, with one early exception, maintained the same line

up throughout their career. In terms of album sales alone, Rush are only

bested by The Beatles (four members) and The Rolling Stones (five members).

So, from a mathematical standpoint alone, they offer the highest ratio of

talent per player to quantifiable success. Numbers and statistics really matter

to some people. For the trio from Ontario, not so much. They just wanted to

play the music they wanted to play, their way or not at all. It was only and

always the music that mattered. Everything that followed (fame, fortune and

occasional despair) was merely a consequence of doing what they were best

at, a fact that many legions of fans across the globe can attest to.

This book reviews the band’s output from their debut album in 1974 to

1982’s Signals — a pivotal album that saw the trio immerse themselves more

und more in the prevailing musical trends of the period (New Wave, ska, and

reggae). Signals was also the final album that long-term producer and

unofficial fourth man Terry Brown would work on with the band. I refer to

the incarnation of the band with John Rutsey as Rush 1.0 and his seminal

replacement with Neil Peart as Rush 2.0.

Becoming one of the most successful power trios in the history of rock was

not bad work for three adolescents who saw themselves as outsiders in their

teenage Toronto suburbs, finding solace, focus, and a future in music. And

even with all their accumulated fame and fortune, Lee, Lifeson, and Peart

never felt part of the mainstream, revelling in being regarded as the ‘world’s

largest cult band’. As musicians, Rush have enjoyed enormous respect and

have consistently appeared at the top of critics’ lists for their instrumental

mastery. They have been nominated for 35 Juno Awards; they were Canada’s

‘Group of the Decade’ in the 1980s and were named ‘Musicians of the

Millennium’ by the Harvard Lampoon, the satirical magazine; a joke that the

band were happy to receive as a foil to their perceived seriousness.

Weinrib (Lee) and Zivojinovic (Lifeson) met at Fisherville Junior High, in the

Willowdale district of Toronto. They bonded over jokes, sports and especially

music. In a 2016 interview with Classic Rock magazitie; Alex remembered that

they became best friends, while Geddy recalled:

We were sons of Eastern European immigrants who had left Europe after the Second World War to start a new life in Canada. So we were both a little bit different. My parents were Polish Jews, survivors of the Holocaust. They met when they were thirteen at a work camp, and they were both in Auschwitz for a time. My mom had such a strong Jewish accent, which is how I ended up being known as Geddy instead of Gary, my real name and basically, it stuck.

Alex continued:

I'm a first-generation Canadian. Both my parents were Serbian. They actually met in Canada after the war. They had come over as refugees. My father had been married before, to a Serbian woman. They had married in Italy, and my sister was born there. They tried to get into the States, but they were denied and then sent to Canada. In cities like Toronto, they didn’t really want these people, but Eastern Europeans could find work in the mines in British Columbia, and my mother’s family worked on a farm. My father’s first wife died, and some years later, he met my mother. We eventually moved to Toronto in the early 50s because there were greater opportunities there.

Across the road from the Lifeson family lived the Rutseys, and Alex befriended

their son, John. Geddy and Alex soon acquired guitars and jammed together at

school. Afterwards, they would frequently go their separate ways with Alex

playing music with John, who had a set of drums. Alex and Geddy would

perform together occasionally, especially after Geddy acquired an amplifier.

Rutsey and Lifeson formed a band called The Projection, with Jeff Jones on

bass and vocals. It was Bill Rutsey, John’s brother, who suggested a name

change to Rush. By the spring of 1968, Geddy, too, had joined his first band, a

loan from his mother securing him his first bass.

In September 1968, Rush were offered a regular, paid gig on Friday nights

at The Coff-In, a coffee bar in a church basement. While Rutsey and Lifeson

were excited by the development, Jones didn’t share their enthusiasm and

didn’t show up for the show. Alex called Geddy to fill in, and after a short

rehearsal, he joined the band. It was also at The Coff-In that the band was

noticed by a young promoter-to-be, Ray Danniels. In the Classic Rock

interview, Geddy remembered:

I was a pretty shy kid. I didn’t really want to be a frontman. I was just the one with the best voice — or the most appropriate voice! So, stepping out in front was not a natural thing for me. I had to learn how to deal with it. John used to announce the songs, and he was totally good at it, really funny, a real acerbic wit. And in those early days, John was the leader of the band, to all intents and purposes. He was a very opinionated guy — about music, about what he thought the band should be, how we should look.

In Martin Popoff’s book Contents Under Pressure, Alex gave an insight into the band’s earliest gigs:

We knew maybe seven or eight songs — mostly Cream and Hendrix — and we would just play them over and over, repeatedly throughout the night. And through the rest of the week, we would get together and rehearse and learn more songs. We started writing right from the beginning. And we continued doing that gig pretty much on a weekly basis until the spring of 1969. The first gig we played there, there were probably 30 people. By that spring, there were about 200, 250 people. The place was packed. And we had two solid sets of material, and that was a real treat; it was so exciting. We got ten bucks for that first gig. And by the spring, we were getting 35 bucks a week, so it was quite a big increase. Then we started playing high school dances, other drop-in centres, things like that. We continued doing that for the most part until “71, I guess when they lowered the drinking age to 18. And then, all of a sudden, there were all these bars you could play in.

The band started to write as much original material as they could, slotting new creations into their sets, which were otherwise dominated by the music of Led Zeppelin, Cream, Jimi Hendrix and The Who. In the Classic Rock interview, Alex noted:

It was a really great training period for us. At first, the gigs were indifferent, not much interest, maybe a dozen people. But the better that we got at it, we started to develop a following. Word spread, and we became a good draw.

After a year of playing clubs, the shows were packed.

Danniels volunteered to be the band’s manager. Bookings flowed in, and

rehearsals, repertoire, and equipment increased. The musical emphasis shifted

from the blues-rock stylings of Cream to the heavier side of the Led Zeppelin

sound, with Lee adapting his singing style accordingly. Lyric writing for the

band’s growing repertoire of original material fell to Rutsey as neither Lee nor

Lifeson were confident in their ability as wordsmiths. Belief in their

songwriting grew with more of their own songs featuring in gigs, although

Rutsey was less enthusiastic about the developing musical direction preferred

by Lifeson and Lee.

Rush decided to turn professional. Soon, they were gigging most nights of

the week, although venues reacted less favourably when they played at

excessive volume or performed their own unknown compositions. By the end

of 1971, they had a regular gig at the Abbey Road pub, which paid $1,000 a

time. This meant an investment in better equipment and transportation.

By the end of 1972, the band’s reputation was building. Hard work on the

live circuit ensured an expanding fan base, the balance between cover songs

and original material was shifting still further, and they had enough material to record an album. A lengthy demo tape was sent to Canadian record

companies, who summarily rejected the trio. Unrepentant, they continued

with regular gigging.

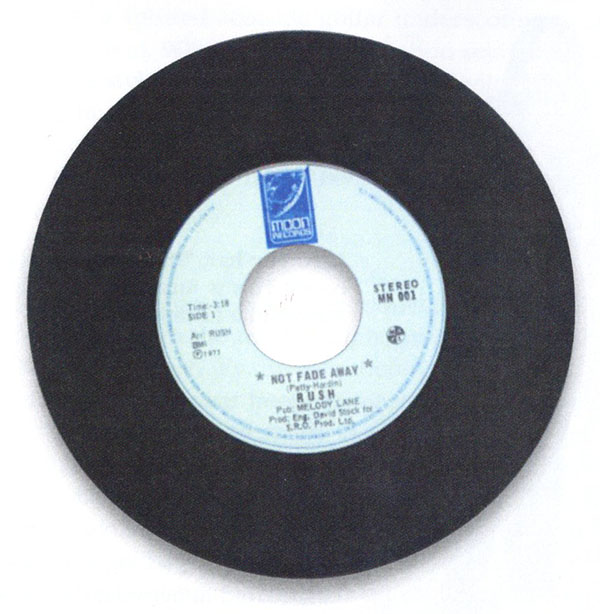

In early 1973, Danniels joined forces with another promoter, Vic Wilson, to

form SRO (Standing Room Only) Productions. Danniels and Wilson

encouraged the band to release a single and created their own record label,

Moon Records. Fearing that Rush’s own compositions might not be the

winning hand to play, the band were persuaded to cover the Buddy Holly

song ‘Not Fade Away’, with an original tune, ‘You Can’t Fight It’ as the B-side.

These were recorded at Eastern Sound Studios in Toronto under the clueless

direction of David Stock.

A few hundred copies were pressed, with Danniels going into promotional

overdrive with record companies and radio stations, all to no avail. The single

vanished into rightful obscurity, with the remaining copies being sold at a

loss at gigs. The first time I heard these songs was thanks to a recording

placed on YouTube. The single has never been formally re-released or added

as a bonus track to a CD, which, in all honesty, we should all be thankful for.

Not Fade Away Single

‘Not Fade Away’ (Norman Petty/Charles Hardin) (3.15)

Buddy Holly’s famous song from 1957 gets an early mauling, the band taking

inspiration for their performance from The Rolling Stones’ own cover version

of the track released in 1964.

The vocals? Well, the word ‘helium’ springs to mind. Lee’s double-tracked

voice sounds just plain weird in the context of this famous song. It’s easy to

understand why this version of the band struggled to secure a record deal.

As a piece of Rush history ‘Not Fade Away’ is an interesting curio, but it

does nothing at all to suggest future glories. The recorded sound is weak

and underpowered; Rutsey sounds like he is playing on shoe boxes, and

while the guitar has some excellent power-chord moments, the bass merely

burbles away in the background. This cover of a cover of a classic pop hit

goes on for too long, illustrated by a curious ‘vocals only’ section at 2.10.

This is where it should have stopped, but then we are at least treated to an

early example of Lifeson’s talent with a bluesy, distorted guitar solo in the

overly long play-out.

‘You Can’t Fight It’ (Lee/Rutsey) (2.52)

This is, strangely, more like it, but only given that ‘Not Fade Away’ is such a

low bar to get over. “You Can’t Fight It’ is an energetic bluesy composition with

an interesting ‘heavy country’ opening riff and Lee sounding more like, well,

himself. Rutsey has some decent drum fills in the chorus, and Lifeson throws

in another impressive solo, full of attack and melody. The track comes across

as a heavy pop-rock shuffle with plenty of musical ideas allied to some truly

dreadful lyrics: ‘Rock and roll ‘til you lose control. Go down, fall down, not too far’. Despite this terrible handicap, “You Can’t Fight It’ is markedly better than the A-side, although the clichéd, big rock ending does it no favours.

In the Classic Rock interview, Alex recalled:

It was a song that people knew and could identify with, rather than an original Rush song. The feeling from management was: let’s do something that people will get as an introduction. I think that was bad advice. Playing that song live was great. We played it quite heavy. It sounded really good. But the recorded version was terrible.

In the absence of outside interest, Danniels decided that the band should

release an independent album as a calling card. This was recorded in five

days, on a very tight budget, at Eastern Sound, with the inexperienced Stock

once again behind the desk. By now, Rutsey was feeling pressure from two

directions. A diabetes sufferer, the band’s punishing schedule was damaging

his health, and he wasn’t happy with Lifeson’s and Lee’s emerging and

preferred progressive rock direction.

In the absence of outside interest, Danniels decided that the band should

release an independent album as a calling card. This was recorded in five

days, on a very tight budget, at Eastern Sound, with the inexperienced Stock

once again behind the desk. By now, Rutsey was feeling pressure from two

directions. A diabetes sufferer, the band’s punishing schedule was damaging

his health, and he wasn’t happy with Lifeson’s and Lee’s emerging and

preferred progressive rock direction.

Vic Wilson suggested a fresh pair of hands and ears might perform the

required trick. Terry Brown had been an engineer back in the United

Kingdom, from where he hailed, before moving to Canada in 1969. With his

business partner Douglas Riley, Brown opened Toronto Sound in the same

year. SRO provided the funds for a remixing of the songs. Brown also offered

a critical ear and suggested that ‘Not Fade Away’ be dropped in favour of

another band original, ‘Finding My Way’. “You Can’t Fight It’ similarly bit the

proverbial studio dust. In Anthem — Rush In The Seventies, also by Martin

Popoff, Geddy reflected upon the significance of Brown’s input and effect on

the nascent Rush sound:

He just had this air of ‘I know what’s wrong with it, and I know which songs are lousy, which you should drop, and do you have any other songs?’ And we threw some songs together and played them, and he picked A, B, and C, and we thought, ‘This guy is really cool, this guy knows what he’s doing.’ And then we went into his studio and started re-recording some parts and recording the new songs, and they sounded how we wanted them to sound. And we were just so blown away by that; he became the father figure right away. He turned a terrible disaster into something we were proud of — he knew exactly what to do. He was kind of a wizard character to us. We thought he was amazing. He was so nice and so considerate and got the best out of us, and we immediately had this warm feeling about the guy. He became our mentor for a lot of reasons like that. He was always very clecisive with us. And he was always so “This is the right thing to do; this is not the right thing’ He had a very responsible attitude towards work, and he would work all hours.

RUSH

Personnel:

Geddy Lee: lead vocals, bass

Alex Lifeson: guitars, backing vocals

John Rutsey: drums, percussion, backing vocals

Recording locations:

‘Finding My Way’, ‘Need Some Love’ and ‘Here Again’: Toronto Sound Studios

‘Take A Friend’ and ‘In The Mood’: Eastern Sound Studios

‘What You’re Doing’, ‘Before And After’ and ‘Working Man’: Eastern Sound Studios, remixed by Terry Brown at Toronto Sound

Released: 1 March 1974 on Moon Records [sic]

All tracks by Lee and Lifeson, unless noted

Produced by Rush and Terry Brown

All songs composed by Lee & Lifeson, except ‘In The Mood’ by Lee

Chart positions: Canada: 86, US: 105, UK: did not chart

Terry Brown knew exactly what he was doing. He captured a far more

immediate, aggressive and realistic sound of Rush 1.0 in his studio, and an

excited band prepared to unleash their first offering on the world to initially

very little effect...

When is a Rush album not a Rush album? Rush is the sound of a band,

ahem, finding their way. For fans that joined post-Peart, this is the release that

doesn’t sound ‘right’. My own early Rush buying experience went backwards

in time, starting with All The World’s A Stage as a ‘taster’ and then, once

hooked, buying the other four albums in reverse order, as it were. By the time

I got to Rush, I did wonder whether the right vinyl had been placed in the

single sleeve — it was that strange. Only Lee’s vocals and the pounding

heaviness of Lifeson’s guitar convinced me that I hadn’t been sold a dud.

Whilst the music is decidedly different to that of the early post-Peart

performances, showing strong signs of the band’s early influences, the main

problem is the lyrics. During pre-recording rehearsals, Rutsey, the main

writer, destroyed his work at the last minute. Accounts vary as to why this

happened; Rutsey was plagued by bad moods, he had health issues and Lee

is on record as believing that Rutsey actually feared success. Whatever the

truth, at this crucial stage in the band’s career, they had the music but not the

words. The job was left to Lee. And it shows. Geddy takes much of the blame

and credit for completing this race under pressure.

The cover, a garish affair, was by Paul Weldon. Of course, this being an

album which did not have the backing of a major label, the cloth must be cut

accordingly. At least the design leaves the purchaser in no doubt as to what

they are going to hear; the artwork is as much ‘in your face’ as the sound is

‘in your ears’. Basic, but effective. The now iconic eponymous title logo is

bright pink (the original pressing was issued in red), exploding towards us

with cartoon-style debris in the background. Designed to portray the music’s power and energy, it just looks, unsurprisingly, cheap. On the reverse, the

band are shown as individual black and white head-shot rocks flying towards

us. Lifeson has a typical ‘serious rock’ look; Rutsey is, bizarrely, smiling, and

lee wears his best poker face expression. All three are backlit to suggest

more power coming from (beneath, between) and behind them.

‘Finding My Way’ (5.05)

Things get off to a reasonably satisfying, if unspectacular, start. Notable

mainly for the distinctive vocals and melodically aggressive guitar work,

‘Finding My Way’ is a solid lump of four-to-the-floor, early Zeppelin-esque,

heavy blues rock.

It fades in with a riff panning left to right in the stereo channels; Lee

makes a dramatic appearance with ‘Yeah, oh yeah’ and continues with the

sub-optimal lyrics (‘Who am I? I’m coming out to getcha!’), straight out of

the Robert Plant playbook. Bass and drums add musical stabs and a steady

rhythmic tempo sets in at 0.46. Far away from the lyrical themes which

Rush version two would explore, the chorus begins with ‘I’m finding,

finding my way back home.’ Where, exactly, have you been? This

conundrum is never resolved.

A second verse and chorus lead into a new ‘walking blues’ riff at 2.29, a

further chorus line, and a first solo for Lifeson, which is played out over the

verse chord progression. At 3.37, there is a more interesting instrumental

section with some harmonised guitar lines in between Lee’s ‘Shah!’ vocals.

Another chorus is followed by a brief repeat of the introduction. Verse one

was so good that apparently it is granted a reappearance as the last

instalment with a final chorus before the song comes to a tight close.’ ‘Finding

My Way’ is a decent opener, but that’s all it is.

‘Need Some Love’ (2.19)

‘Need Some Love’ (2.19)

Oh dear. ‘I’m running here, I’m running there, I’m looking for a girl’ The rest

of the first verse gets no better and ‘Need Some Love’ is a prime example of

why record companies heard nothing to electrify the ears when they listened

to the album.

This was the first original song to be recorded. According to an interview

Lifeson gave to MusicRadar in 2011, it was written by Rutsey and Lee,

although Lifeson is often credited as Lee’s writing partner for the track. Lyrics

notwithstanding, ‘Need Some Love’ is a brisk little blues rocker which slows

to a half-time feel for the choruses.

Interest is awakened after the second chorus with a heavy instrumental

section (1.22 - 1.50), which features some excellent slide guitar playing and

i suitably anguished-sounding, bluesy solo. After the third chorus, this

section is briefly repeated, leading to another crisp ending. Unspectacular

and mostly disappointing, at least ‘Need Some Love’ doesn’t trouble the ears

for too long.

‘Take A Friend’ (4.24)

If you ever need to organise a rock music trivia pub quiz, have this one on me:

What's the connection between the 21*-century English pop-rock band McFly and legendary Canadian progressive rockers Rush?

The answer is the opening 30 seconds of McFly’s 2023 song ‘Land Of The

Bees’ and the introduction to ‘Take A Friend’. They say ‘inspired by’; I say

‘carbon copy of, with a few extra notes added’. McFly have admitted to a

strong liking for Rush’s music. Lee and Lifeson have yet to return the

compliment. Despite this similarity, the listener’s attention is immediately

engaged. Oddly, this is the only time, to my limited knowledge, that McFly

have incorporated Rush’s influence into their music. True, their respective

styles are not exactly congruent. True, this is an apparent one-off. Yet, it’s an

intriguing link between two very different bands.

Okay, beer glasses down, back to the track. Initially, ‘Take A Friend’ shows

real promise. A revolving, rising arpeggio pattern in 6/8 time fades in, adding

some interesting parallel fifth and octave harmonies. This first showing of

semi-prog inventiveness comes to an end 27 seconds in, as a medium-tempo

riff of vaguely Lynyrd Skynyrd-esque proportions lumbers over the horizon

and squats over most of the rest of the track.

The chorus has some nicely harmonised vocals, culminating in ‘So good!’

which a healthy dose of delay has added to it. After a second verse and

chorus, Lifeson has a stirring solo despite the restrictions of the underlying

chord sequence. By 2.49, it’s time for a third verse which maintains the lyrical

quality established thus far: ‘Yes, you need some advice, so let me put it to

you nice.’ Another chorus, then a fourth and a fifth (it’s not that good) verse

follow, and then, suddenly, the music takes a savage and unexpected left-

hand turn back to the introduction. The arpeggios slow, a lot of reverb is

added to the mix, and the track slows to a puzzling, inconclusive close.

In a 2023 interview with Laura Cooney for Entertainment Forum, Danny

Jones said “Land Of The Bees’ (was) our first ever song that was inspired by

Rush. (It) has a 7/4 time signature in it, and if you don’t concentrate through

that one, you’re gonna get lost!”

Seriously, though, give the McFly song a listen. It’s really good ... and if you

must steal, steal from the best. Yes, Tom Fletcher, I’m looking at you!

‘Here Again’ (7.34)

Ballad Warning! Slower of speed and more spacious in texture, with some

unexpected acoustic guitar behind the verse vocals, ‘Here Again’ is a welcome

change of pace and mood. Again, the blues is strong in this one, with Lee

straining at the top of his range, full of emotion as he sings Lifeson’s lyrics.

There are some beautiful guitar arpeggios washing to and fro in the

background, growing ever more powerful. Finally, at the end of the second verse, the music moves from its minor key (Em) into the relative major (G) for

the soaring chorus. This is the best section of the track and the album thus

fur; it’s strong, highly melodic, and possesses an epic stature and power.

At 4.37, Lifeson steps forward for a lengthy, tasteful solo, which makes

much use of the space between his notes and phrases to create an impressive

utmosphere. Although being firmly rooted in the blues his playing shows

plenty of sparks of genuine originality and feel. The lines rise and fall against

the underlying chord progression, growing in intensity and complexity but

never losing sight of the importance of a melodic structure. At 6.33, the

chorus reappears to bring this impressive beast to a close with a final solo

over the chorus chord sequence and a slowing to the last chord.

‘What You’re Doing’ (4.22)

‘Ladies and Gentlemen, will you please welcome back ... Led Zeppelin!’ Well,

obviously not, but Jimmy Page could lay fair claim to writing the excellent

funk-based riff, which is the backbone of this track. Lee’s vocals and lyrics

also have echoes of Robert Plant. After markedly derivative first and second

verses, things become more interesting at 1.08 with a descending seven-note

semitone-based riff with the guitar and bass playing in octaves. Verse three

follows, with a guitar solo appearing at 2.03.

Again, individuality raises its worthy head at 2.31, where his repeated

descending phrase is matched by some thunderous drumming (this is the first

time where Rutsey has sounded like anything more than necessary aural

wallpaper), and this idea is repeated at 2.41, and again, very briefly, at 2.50. The

repeated, descending semitone riff makes a reappearance before the fourth verse

at 3.27, ending with a section of big power chords and some fretboard flurries.

‘What You’re Doing’ has some genuine moments of inspiration, but these

are swamped by the band wearing their influences so openly on their sleeves.

There’s nothing wrong with admiring Led Zeppelin, of course, but “What

You’re Doing’ has more going for it and would be stronger if Rush’s latent

creativity was front and centre of the composition.

‘In The Mood’ (Lee) (3.33)

‘And the award for ‘Dullest Song on the Debut’ goes to ...’ Well, it’s a close

run thing, but ‘In The Mood’ just clinches it. Whether it’s the sluggish opening

riff, the irritating cowbell, the general lack of genuine rock energy, or the

woeful words, there’s very little here to raise the pulse rate.

The chorus, while musically strong, is lyrically awful: ‘Hey baby, it’s a quarter

to eight, I feel I’m in the mood. Hey baby, the hour is late, I feel I’ve got to

move.’ Without wishing to pick unnecessary, if glaring, holes, ‘a quarter to eight’

is not, unless you are very elderly or seriously infirm, a late hour. ‘In The Mood’

is your standard blues-rock stop-gap, and even Lifeson’s solo at 1.40 sounds

like he is merely playing through the motions, not helped by the underpowered

tempo or the overall sense of underachievement in all departments.

Another chorus, a repeat of the main riff, and a final verse including the

painful words ‘T just want to rock and roll you woman, till the night is done’

sets up the ‘can’t come too soon’ ending of a brisk power chord finish. :

Bearing in mind this is the “Terry Brown enhanced’ mix, one can only

imagine how woeful ‘In The Mood’ would have sounded if the calloused and _

clumsy production fingers of David Stock had got to grips with this track.

That’s one mix I would pay good money not to have to listen to.

Strangely, ‘In The Mood’ would feature in the band’s live set for farlonger

than it should. It’s fair enough that during the very early years with Peart, the _

band would play material from their debut album on stage, but almost any

other track from Rush would have been a preferable choice. Yes, ‘In The

Mood’ would sound better and more energetic in a live setting (almost any

song does), but it’s still the low point here.

‘Before And After’ (5.34)

‘Before And After’ is two songs in one, each independent of the other. It is

also the first song which hints at where Lifeson and Lee had their sights set.

The opening part (which lasts until 2.17) is entirely instrumental. It is quite

beautiful, with an evocative blend of guitar arpeggios and ‘natural’ harmonics

(the bell-like tones produced by touching a string directly above a fret rather

than pressing the string into the guitar fretboard). The music builds until at

1.11 where a distorted guitar develops the chord progression, with Lee taking

a more prominent role in the mix. We can hear here Lee’s development of the

bass as the integral, melodic element of the band’s future sound. The music

quietens again at 1.48, with a nice interplay between bass and cymbals. The

chords grow in power and suddenly, we are into the second song at 2.17.

And it is at this point that all that is good is swiftly undone with the return

of the blues-rock sound. There’s nothing wrong with this chugging rocker, but

this section lacks the creativity and melodic strength of the ‘Before’ section.

The track becomes heavily drum-centric at 3.16 and is helped by a soaring

contribution from Lifeson at 3.48. The final verse features the lines ‘Now my

story’s over’ and it was at this point when writing my notes for this review I

realised I hadn’t been paying a blind bit of attention to what the lyrics were

about, which speaks volumes. The song reaches an excellent climax with Lee

putting his voice under maximum stress for the final rising ‘Yeah’!

‘Working Man’ (7.10)

And here it is! This is the perfect example of saving the very best until the

last. “Working Man’ gave the band a foothold on success. It opens with a

crushing guitar riff of industrial proportions and ferocity. This introduction

alone pushes the majority of the rest of Rush into the shade as the track

gathers power and proceeds to demolish listeners in its path. Brilliant in its

simplicity and epic in its scope, it’s easy to see why ‘Working Man’ became

adopted as an anthem, initially in Cleveland, but slowly spreading worldwide with its central, universal refrain: ‘It seems to me I could live my life, a lot

better than I think I am’ finding resonance with millions of wage slaves

everywhere.

Lee wrote all of the words to this now-classic song the evening before the

vocals were due to be recorded.

The song breaks loose from its verse/chorus/repeat structure at 2.06, going

into a lengthy, double-time instrumental section, which is the highlight of the

entire album. Here, Lifeson has plenty of space to develop his solo, which

builds to a fantastic riff played in octaves with Lee at 3.13. Further

individualistic soloing follows with the entire section feeling both

simultaneously improvised and tightly arranged. The ‘octaves riff’ reappears

again at 4,34, and at the five-minute mark, the instrumental concludes with

some heavy power-chording. This builds back into the main song riff and the

final verse, which is a straight repeat of the first time we heard it.

I may be overthinking this, but if the preceding instrumental (which has

been played out almost entirely based around E minor represented the

‘working day’), then the anticipated next verse could have described the

narrator’s situation, having completed his relentless slog. Or the instrumental

is the narrator letting his hair down at the end of the working day or at a

weekend before the seemingly endless repetition of the grind starts up again.

Just me? Fair enough.

A vast swathe of power chords brings this instant classic to an end; the

music slows as if tired after its exertions, with a country-esque series of

accelerating guitar string bends which leads to the ‘very-much-of-its-time’ big

rock ending.

‘Working Man’ stands head and shoulders above everything else on the

album, and whilst the inspirations are clear, it still has more than enough

class, individuality and sense of purpose to justify its now ‘classic’ status. It’s

probably fair to say that, without this song, the band’s future would have

been very, very different.

FLY BY NIGHT

Personnel:

Alex Lifeson: Electric guitars, six and 12-string acoustic guitars

Geddy Lee: bass guitar, classical guitar, vocals

Neil Peart: drums and percussion

Recorded at Toronto Sound Studios, Toronto

Produced by Rush and Terry Brown

Released: 15 February 1975 on Mercury Records

All music composed by Lee & Lifeson with lyrics by Peart, except where noted

Chart positions: Canada: 9, US: 113, UK: did not chart

After the release of Rush, SRO continued to attempt, unsuccessfully, to sign

the band to a record label. FM radio, however, proved more receptive. The

breakthrough came when Donna Halper, music director for WMMS-FM in

Cleveland, heard the album. She was immediately struck by ‘Working Man’,

and the station played it to an instant and positive reaction from listeners.

Before long, almost all of the first 3500 pressings had been shipped to

Record Revolution, an import specialist music store in Cleveland. Ira Blacker

of the booking and management agency American Talent International (ATD

was impressed enough to send copies to record labels, recommending that

they give it a constructive listen. Mercury Records finally signed the band in

June 1974. The contract granted Rush complete artistic freedom. Little did

Mercury know what they were letting themselves in for. At this ‘Pre-Peart-

Point’, neither did Lifeson or Lee. Mercury, SRO, and ATI began to work Rush

overtime. The album was quickly re-pressed and re-released.

Rutsey, however, wasn’t as ambitious as his bandmates. All three knew that

a crossroads was just over the horizon. Lee and Lifeson were musically joined

at the hip; Rutsey was isolated and had issues with his health due to diabetes.

Perhaps taking the view that quitting was better than being sacked, Rutsey

left, leaving a drummer-sized hole of a problem. In Contents Under Pressure,

Alex commented on the situation:

We were placed to do this tour and go to America and all of what that meant, but (John) backed out at the time. Plus he also wasn’t really interested in where we wanted to go musically. We wanted to move our music into a more progressive area, and he was more straight-ahead rock ‘n’ roll, which was more of a cross-section of what we were playing in bars at that time. So it was really time to go our separate directions. We liked to play hard rock as a three- piece, but we wanted it to be more challenging, mostly musically, to ourselves.

A replacement shed builder had to be found, and very, very quickly. Paul

Kersey, the drummer with the Sarnia-based rock band Max Webster (who

would feature regularly as a support act during Rush’s early touring years)

was asked to join but declined. Rutsey agreed to play out his notice, honouring some theatre-sized gigs, including support slots for Kiss and ZZ

‘lop. Lee and Lifeson auditioned for replacements, hiring a warehouse in

Pickering, eastern Toronto, for two days. The first day’s interviewees left them

feeling disillusioned. On the second day, Neil Peart walked in.

A perpetual introvert, Peart did not enjoy school life. He refused to

compromise his identity to try and fit in. Suffering was a predictable

consequence, but this only served to drive him to become even more of a

non-conformist. Drumming was his release. In Rush — Beyond The Lighted

Stage, the documentary DVD released in 2010, he recalled his schooldays:

Once I got interested in rock bands ... and started to grow my hair a little over my ears and wear bellbottoms, ... and the taunting in the hallways and even the physical abuse out in the smoking area, the constant misfit sense for any kid, especially a sensitive one — it wears you down. So, that’s why drumming became an instrument of self-esteem. This was the first time I was admired for anything. And that doubled my fervour for playing drums.

By the age of 15, Peart was playing in public, a hobby his parents fully upproved of. He joined his first band, Mumblin’ Somethin’, and persuaded his father to finance a loan for a proper Rogers drum kit. From that point on, the drums became his all-consuming passion. He would practice for long periods on a daily basis, learning songs and drum techniques by listening to the radio. In the DVD Classic Albums — 2112 And Moving Pictures, Neil said:

Every time I would hear a Bill Bruford or a Phil Collins, it was ‘okay, that’s how good you have to be now. The benchmark went up so high from the early ’60s (where) all you had to do was keep a surf beat and you could get in a band. By the late ‘60s, you had to be able to play in 7/8; you had to be able to transmit through tempo changes and maybe play some keyboard percussion. This was how good you had to be.

After Mumblin’ Somethin’ ceased, Neil, still a teenager, joined another

established local band, J R Flood. He persuaded his parents to let him quit

school and go into music on a full-time basis. J R Flood also allowed Peart to

try out his lyric writing skills. In a neat parallel with Lee and Lifeson, Neil was

more ambitious than his bandmates. He wanted to be in a band that hada

record deal.

By the close of 1971, J R Flood’s time in the local limelight was over, and

Peart decided to move to London to seek musical success. Armed with his

savings, drum kit, and record collection, he crossed the Atlantic, hoping to get

a foot in the door of English rock music. Initially playing some minor session

work, he eventually joined and toured with English Rose, a London-based

rock band, but the experience left him disappointed. He went back to Canada

for Christmas and a rethink. On his return to London, he worked in a Carnaby Street gift shop with jazz music and extensive reading filling his leisure time.

During 1972, he continued to seek out new musical opportunities, but with

little success. He returned home permanently at Christmas and began

working part-time for his father’s farm machinery dealership, as well as

joining a local blues and covers rock band, Hush. In Contents Under Pressure,

he remembered:

By the close of 1971, J R Flood’s time in the local limelight was over, and

Peart decided to move to London to seek musical success. Armed with his

savings, drum kit, and record collection, he crossed the Atlantic, hoping to get

a foot in the door of English rock music. Initially playing some minor session

work, he eventually joined and toured with English Rose, a London-based

rock band, but the experience left him disappointed. He went back to Canada

for Christmas and a rethink. On his return to London, he worked in a Carnaby Street gift shop with jazz music and extensive reading filling his leisure time.

During 1972, he continued to seek out new musical opportunities, but with

little success. He returned home permanently at Christmas and began

working part-time for his father’s farm machinery dealership, as well as

joining a local blues and covers rock band, Hush. In Contents Under Pressure,

he remembered:

I was soon getting disillusioned over there by the music industry, realising it wasn't the way I thought it was. You didn’t just get good at the music you loved and became successful. I was shocked, appalled, disappointed, disillusioned, all that. I also made the decision that if I can’t make a living playing the music I like, then I'll make a living some other way and still play the music I like. That became the point of honour. So, at that time, when the Rush offer came along in the summer of ‘74, I was playing part-time in a band in bars and working all day in the family farm equipment business to make a living.

When Vic Wilson turned up at the dealership and asked Neil if he would be

interested in auditioning for a nearby band, Rush, Neil jumped at the chance.

Rush, after all, had a record deal. Perhaps there was a way that the young

man could make his living doing what he loved after all...

The initial impressions on both sides were not promising. Peart’s

introverted character didn’t shout ‘progressive heavy rock’, and his drum kit

was on the small side, not that size matters. For his part, Peart had heard that

Rush were little more than Zeppelin clones. Nevertheless, he played his heart

out, and a subsequent ‘jam’ session proved to Lifeson and Lee that he was

somebody special. In the Classic Rock interview, Alex said:

We were so blown away by Neil’s playing. It was very Keith Moon-like, very active, and he hit his drums so hard. And then, after we’d jammed, we chatted and he was so bright. We connected on many levels. I have to admit that on that first day, I said to Geddy, ‘You know, maybe we should still hold out and see who else is out there.’ But when we talked again, we were convinced he was the right guy.

Geddy recalled some additional details:

The first thing that we jammed with Neil in his audition was ‘Anthem’. That song was written, for the most part, while John was still in the band. It was very different to any of the songs on the first album — more complex. And Neil coming into the band was a kind of confirming final piece of the puzzle. That was very much where he was at. He liked to play things that were difficult to play, and that was the direction Alex and I were moving in. It had a very catalytic effect.

Peart realised that he had been bruised by his London experiences, and this

was a chance to play drums for a band with a record deal and an American

tour lined up. Even more importantly, Lifeson and Lee shared his ambition to

improve and succeed. Peart officially joined on 29 July 1974, Lee’s 21* birthday.

Two weeks later, after intensive rehearsals, the ‘new’ band went back on

tour. Baptisms of fire don’t come much hotter than 11,000 rock fans at the

Civic Arena in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Rush were the support act for Uriah

Hleep and Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. If Peart was nervous it didn’t show in

his performance. His arrival and integration into Rush was, of course, utterly

transformative; all three felt they could now go in a direction, any direction,

that they wanted to. So they did.

A week after the first ‘new’ Rush gig, the band played the Agora Ballroom,

Cleveland, which was broadcast live on WMMS-FM. As the band continued to

tour, the music they were creating expanded in style and complexity. Rush

ippeared on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert, broadcast on 10 October 1974,

which helped the debut album into the Billboard charts. Further exposure via

iin appearance on ABC Television’s In Concert series assisted sales, and the

tour concluded on Christmas Day 1974, back at the Agora.

The work was paying off. Rush had sold over 75,000 copies by the end of

the year. What was needed was a follow-up and fast. New material had been

written on the road, rehearsed, and polished so that the band felt ready to

return to the studio in January 1975. Toronto Sound and Terry Brown were

natural choices.

Both Lee and Lifeson were savvy enough to know that lyric writing wasn’t

their forte or their interest, and the ‘new boy’ (as Peart would sometimes be

referred to right up until the band retired), with his love of books and his

eclectic reading interests, seemed an ideal lyric-writing candidate. Peart was,

therefore, gently pushed into one of the roles he was born for. His intellect,

vocabulary and insights, even at this early stage of the band’s eventual

planetary domination, were significant and long-lasting.

Travel, excitement, and opportunity are underlying themes of the album. If

a record is judged by its cover alone, then Fly By Night was going to be a very

different beast indeed. The stunning image of a massive owl perched on a

snowy landscape at night was painted by Eraldo Carugati, based on an idea

by Peart, a keen ornithologist. The band also wanted the cover to feature an

aeroplane and the Northern Lights, as the album’s working title was Aurora

Borealis. On the back of the sleeve, the image continues, with the owl’s right

wing hanging over the three individual colour photos of Lifeson (moodily

looking on from an angle), Peart (straight ahead, serious face), and Lee (more

hair than facial features). The inside liner cover included black and white

photos of the band, producer Terry Brown, and Howard Ungerleider, the

band’s lighting designer, pictured amongst Peart’s handwritten lyric sheets

(not in running order), all laid out on the recording desk. In the Classic Rock

interview, Geddy said:

‘Anthem’ was a holdover. Pretty much everything else on that album was written fresh. With a lot of the songs on that record, the music came first. But sometimes, Neil would have a lyric and Alex and I would put the music to it. There was also a lot of diversity on Fly By Night, much more than on the first album. We wanted each song to show another side to the band.

Fly By Night is a giant leap into a bold new future. Sonic colours abound,

from the crushingly heavy power of ‘Anthem’, ‘Beneath, Between And

Behind’, and ‘By-Tor And The Snow Dog’, to the moments of sublime beauty

CRivendell’), strongly melodic rockers (the title track, and ‘In The End’,) and

the lighter acoustic drive of ‘Making Memories’. ‘Best I Can’ is old Rush with a

new drummer; Peart’s contribution lifts an otherwise mundane rocker into

something stronger.

There is much sonic light and shade; the prominent use of steel-strung

acoustic and nylon ‘classical’ guitars add much contrast to the differing song

styles. Lifeson’s electric sounds are magnificent, with ‘the song’ always at the

centre of his playing. Lee’s bass work and sound are instantly impressive, his

vocals spanning a far greater range of emotions and ability than was

previously suggested. And Peart, both as drummer and lyricist, delivers in

spades. His forays into the world of fantasy do not jar with the personal

reflections garnered from his travelling. The lyrics are intelligent, erudite, and

relatable. The overall impression is of an established, integrated unit knowing

what they want to achieve and presenting an original project.

Whilst Rutsey was integral to getting the Rush ball rolling, there is a clear

sense that, with Peart on board, the trio now had the potential to become

something very special indeed. Listening through to the album again years

later, it’s this sense of anticipation, excitement and the musical unknown

which is so enticing. They were young, they were ambitious, they had worked

hard to get where they were and there was absolutely no sense that anything

could stop them creatively.

Criticisms are few and far between. ‘Best I Can’ is a clear leftover from

Rush, ‘Beneath, Between, And Behind’ should have occupied more space on

the vinyl to further develop its musical and lyrical themes whilst, conversely,

‘Rivendell’ outstays its welcome. But these qualms pale in comparison to

what is achieved. Given the period between Peart’s joining and the record’s

release some seven months later, the album is little short of remarkable.

Even now, almost 50 years later, Brown’s production sparkles. There is

Space around the instruments, dynamics and different sound textures

flourish, many moods are created, none of the songs sound like any of the

others, and yet they all have a unifying style running through them. The

overall impression is one of enthusiasm, energy, focused talent and

ambition, all distilled into a brisk demonstration of where the band could

be going next.

‘Anthem’ (4.21)

To para-(diddle)-phrase, ‘what a difference a drumming lyricist makes’.

‘Anthem’ encompasses many of the hallmarks of Rush’s music of the 1970s:

unusual time signatures, guitar and bass playing complex melodies, and

elaborate drum fills. It also introduces the lyrical theme for which Rush

would become renowned: individualism.

At the time, Peart was influenced by the writing of the Russian-born

American author Ayn Rand (1905 - 1982). Rand defected to the United States

in 1926 and embraced elements of American society: liberty, individualism,

capitalism and the importance of constitutional rights. Peart took some of the

themes of her book ‘Anthem’ and incorporated them into his lyrics. As a

result, Lee is now singing slogans: ‘live for yourself’, ‘hold your head above

the crowd’, and advising people to ‘never let anyone tell you that you owe it

all to me.’ It’s a far cry from where they were less than a year earlier.

Filled with self-confidence and benefiting hugely from the rhythmic

powerhouse of the ‘new boy’, something special comes crashing through the

speakers immediately. The first part of the introduction is fast, complex,

syncopated, and not repeated anywhere else in the song. Some crunchy, rising

power chords are followed quickly by a speedy descending minor scale run in

7/8 time, which is played three times. This is repeated five times, with the rising

sequence being repeated a further three times.

A pick-scrape (a guitarist’s trick where the side of the plectrum is forcibly slid

over the string winding from the bridge towards the fretting hand) heralds in

the second part of the introduction and the main body of the song. And that’s

all just in the first 30 seconds.

An octave-based guitar riff swings into action with bass and drums

synchronising in a 12/8 rhythm. After all the heaviness and intensity of the

Opening section, the subsequent verse has a more relaxed feel. Things heavy

up for the chorus, climaxing at Lee’s astonishing rising vocal of the word

‘wrought’ where his voice goes into the stratosphere over the secondary riff

pattern. A section of stabbed power chords with delay added is played twice

as the music moves into its second verse and chorus.

After the second chorus, the song moves into an instrumental section (2.26

- 3.09) with Lifeson bearing down mightily on his wah-wah pedal to excellent

cffect. When the underlying music incorporates the chorus’s chord

progression, he doubles his melody in the left and right channels with

impressive results.

The ‘octave riff’ brings us back into a third verse and chorus and a coda

section where the stabbed power-chord section is played four times (the third

repeat features an impressive assault around the drum kit) through, leading to

a tight, triplet-based ending.

‘Anthem’ is musically complex yet still melodically accessible, lyrically

original, and very impressive. This is the sound of the three young men

unified in musical purpose. The song is both a superb opener and a statement of intent, a positive sign of things to come, a band on an upward

trajectory...

‘Best I Can’ (3.25) (Lee)

And down again. Delete Peart, reboot Rutsey, and ‘Best I Can’ is a throwback

to the first album. Underpowered both musically and lyrically, the words are

wince-inducing. Exhibit ‘A’ — the first and worst verse: ‘Don’t give me speeches

‘cos they’re all so droll, leave me alone and let me rock and roll’. The second

verse is no better: ‘I just like to please, don’t like to tease, I’m easy like that.

Don’t like long rests I must confess, I’m an impatient cat’. As any owner of a

feline knows, cats do like long rests.

While Lifeson unleashes another wah-wah enhanced solo (1.46 — 2.30), it’s

Pearts’ inventive, vigorous drumming that impresses the most. Throughout the

song, he throws in interesting fills and patterns that raise this otherwise hum-

drum composition to a more engaging level.

‘Beneath, Between And Behind’ (3.01) (Lifeson/Peart)

Now, this is much more like it. An urgent sounding, rising chord sequence,

aggressive drumming, thoughtful lyrics, and a magnificently anthemic chorus

combine to make ‘Beneath, Between And Behind’ an overlooked gem in

Rush’s early catalogue. The words were Peart’s first foray into lyric writing for

his new band.

The chorus is the high point of the song; highly melodic and possessing a

punkish level of energy, it’s the sound of a band enjoying themselves hugely

with an exciting and eloquent composition, covering the birth, history and

then-present day of the United States.

A surprisingly simple climbing riff-based instrumental section (1.37 — 2.00)

leads into a third verse. The lyrics here are a fine example of Peart’s writing

skills, turning his sharp eye towards his geographical neighbours: ‘The guns

replace the plough, facades are tarnished now, the principles have been

betrayed. The dream’s gone stale, but still, let hope prevail, hope that history’s

debt won’t be repaid.’

My only gripe is that this track is too short. There are some wonderful ideas

here which could have been developed further. What they do manage to pack

into just three minutes is superb; I’d just like to hear more of it.

‘By-Tor & The Snow Dog’ (8.37)

In the Classic Rock interview, Geddy said:

The lyrics that Neil wrote for ‘By-Tor & The Snow Dog’ were very tongue-in-cheek. It was a joke that got out of control. Our manager Ray had two dogs, and Howard Ungerleider, our lighting guy, called them Biter and Snow Dog. So Neil took these two names and created fictional characters, and we turned it into a song.

Alex concurred:

Neil made it into this really powerful story - a good-versus-evil fantasy piece. And what came out of that was something much bigger than just one song. In terms of song structure, ‘By-Tor & The Snow Dog’ was the first time that we tried to do a whole multi-part piece of music. It was a pivotal song for the band.

Critics could leap on this, the band’s first ‘epic’ track, with glee. Just the titles

of the song’s four sections would prompt shrieks of ‘pomposity’ and ‘self-

indulgence’ from those who didn’t ‘get it’. Those of us that did just didn’t care,

as ‘By-Tor & The Snow Dog’ is wonderful. To us, no other band was making

music that sounded as good as this, and if you didn’t approve, well, that really was your problem.

Briefly, the plot is this: a demon from hell, By-Tor, attempts to open a portal

to the Overworld, whose champion, Snow Dog, defeats him in combat, thus

saving the living world from the twilight realm of the dead. The composition

consists of four main parts: Verse one, ‘At The Tobes Of Hades’, features By-

Tor. Verse two, ‘Across The Styx’, introduces The Snowdog. ‘Of The Battle’ is a

lengthy instrumental section, and the song concludes with ‘Epilogue’, which is

the third and final verse.

‘Of The Battle’ is sub-divided into four sections, with the titles ‘Challenge

And Defiance’, ‘7/4 War Furore’, ‘Aftermath’ and ‘Hymn Of Triumph’. No doubt

it helped during the mixing stage to have these different parts individually

titled: ‘I need a bit more bottom end in the Aftermath, Terry.’

‘By-Tor’ opened up this listener’s imagination. No other band was balancing

progressive rock music with such incandescent guitars, driving bass, inventive

drumming, and fantastical lyrics, which revealed whole new imaginative

vistas. Powerful, clever, escapist, loud, aggressive and atmospheric, it was a

track like no other to young ears.

There’s no time for mucking about. A brisk drum introduction is

immediately followed by the beginning of the fantasy tale. Verses one and

(wo are swiftly dealt with, the scene being set in just over a minute. The stage

is now ready set for the centrepiece of the composition, the instrumental

battle, which is greeted by an all-mighty “Yeah!’.

For the first two minutes, the song’s tempo is maintained with an intriguing

duet between Lifeson’s wah-wah enhanced guitar and Lee’s heavily distorted

bass, representing the two protagonists. Lee’s tone was achieved by

significantly detuning his bass and adding a Fuzztone pedal to the sound,

which was then passed through an Echoplex pedal to add delay into the mix.

At 3.06, a new melodic theme is established and developed amidst all this

sonic conflict. At 3.30, rhythmic stabs from bass and drums enhance the

effect, and at 3.54, a more complex, octave-based riff section is heard; this is

the band really showing their prog chops. Each melodic cell is followed by a spectacular burst of drumming ability, with each repeat of the riff getting '

shorter and shorter until all that remains is a single, huge power chord :

ending at 4.32.

This drifts into a highly atmospheric section as a violin guitar tone (where

the guitar output is set to zero, the ‘silent’ note is played, and the volume is |

gradually introduced in an effective impression of a sustained note of a :

violin) is treated with reverb and delay to create a beautiful, mysterious effect.

Subtle bass and sparse percussive touches add to the mood. Lifeson changes |

his contribution from single notes to more substantial chords, and the music |

grows with greater drum and percussion activity, moving from a fragile state |

to one of great strength.

A stunning drum roll (to which a phase effect has been added) ushers in the

next part of the instrumental, which is a more traditional guitar solo over a

guitar, bass and drum backing at a slow tempo in 4/4 time. A final short, rising

melody with staccato percussive slabs and the last verse arrives with the results

of the match: By-Tor is defeated, and the ‘lands of the Overworld are saved

again’. ‘Again’? So, this has happened before, then? The track ends with the )

sound of snow crystals, which were etched into the run-off groove on the vinyl |

release. They would ring out endlessly until the needle was removed from the

record. Perhaps the story isn’t over...? After all, the world loves a sequel. With |

one track on the band’s next album, this would come to pass. Sort of.

Yes, with the passing of time and the addition of some (optional) maturity,

Peart’s fantasy tale, and the pretentious titling of this, the album’s longest ,

track may come across as trite and ridiculous. But this is to miss the point. |

Nearly five decades later, ‘By-Tor’ still holds up. Rush were showing their true |

colours and the seemingly limitless possibilities of what they could produce. |

All three musicians contribute equally, with space around the music and an

excellent production showing just what could be achieved. |

The imagination and complexity of the track was a revelation to a teenage

rock fan and while ‘By-Tor’ was the only song on Fly By Night to, ahem, stretch |

its wings thus far, it hinted at where the band may be heading in the future. It

was intoxicating stuff because fans hadn’t heard anything like this before; it

was new and genuinely exciting. This fantastic fantasy is played with precision

and brio, and there’s nothing wrong with escapism when the mood calls.

‘Fly By Night’ (3.21) (Lee/Peart)

A ‘road’ song, if ever there was one, there is a lighter, more optimistic feel to the album’s title track, enhanced by its major key, optimistic lyrics, and a catchy refrain. Lifeson’s solo after the second chorus again shows his skill in playing what fits the song best rather than just careering up and down the fretboard for its own sake. After a third chorus, the track changes direction as a new, more pensive and thoughtful section begins: ‘Start a new chapter...’

Peart must, at this point, have been reflecting on his time in London. Subtle guitar arpeggios and light playing on the bass and percussion increase the introspective mood here. At 2.35, confidence returns for the fourth chorus with the repeated lines, ‘My ship isn’t coming and I just can’t pretend’. The last chorus has these lyrics repeated thrice before the song comes to a final, sustained chord.

‘Fly By Night’ is an excellent example of Rush’s ability to write a short, catchy, and memorable rock song with commercial undertones and, as such, it makes a fine title track.

‘Making Memories’ (2.57)

Another song from the road, but ‘Making Memories’ doesn’t fare as well,

mainly due to its less convincing lyrics: “There’s a time for livin’ as high as we

can, behind us you will only see our dust’ and ‘Well from sea to shining sea,

and a hundred points between, still we go on digging every show’ being the

chief offenders. The chorus, however, speaks to the overall optimistic mood

of the song and the album in general: ‘You know we’re having good days, and

we hope they’re going to last. Our future still looks brighter than our past. We

feel no need to worry, no reason to be sad. Our memories remind us maybe

road life’s not so bad.’

Continuing on the positive side, we have an enthusiastically strummed

acoustic guitar, some excellent hi-hat playing coming in with the second

verse, and Lifeson excelling himself with a wonderful slide solo after the third

verse. The play-out section overstays its welcome with Lee riffing his way

around the words as Lifeson adds numerous fills and the song fades away.

Sadly, ‘Making Memories’ is unexceptional and is second only to ‘Best I Can’

as the most underwhelming track on the album.

‘Rivendell’ (4.57) (Lee/Peart)

An overly long oddity ‘Rivendell’ is notable for its limited instrumentation (a

nylon-strung, classical guitar, Lifeson’s atmospheric ‘violined’ electric guitar

backing) and the first appearance of Lee’s ‘soft’ singing voice. The

combination is dreamlike and hypnotic, and it is in keeping with the intimate,

Tolkein-inspired words. The ambient mood is very effective, and ‘Rivendell’

does show an unexpected but welcome facet to Rush’s songwriting abilities

and ambitions.

Fundamentally, the song consists of an introduction, a verse, and a separate

section. The fact that this is stretched out over nearly five minutes means the

material, good though it is, is spread too thin to maintain interest. If two

minutes had been trimmed off it, ‘Rivendell’ would be a much more involving

composition. As it is, it’s a relief when the final track hoves into view, and the

album springs into life again.

‘In The End’ (6.46) (Lee/Lifeson)

Another ‘Pre-Peart’ piece, ‘In The End’ opens with a beautifully recorded

12-string acoustic guitar chord sequence and the continuation of Lee’s gentle voice, maintaining the tranquil mood established with ‘Rivendell’. Some cymbal ;

washes and gentle bass are added to the opening verse. The lyrics are 4

personal, unspecific, and universal. The words are aligned with the relatively 4

straightforward music to great effect.

The introduction is repeated and the music comes to a pause. The sustained.

pitch rises quietly with some clever studio trickery, and then a strident electri¢

guitar heralds the return of the power trio at 1.43. Lifeson adds some superb,

syncopated octave melody notes above this powerful rhythm, instantly

increasing the power and conviction. Pulsing bass and percussion drive the ]

main, much heavier body of the song, along with the second verse benefiting |

from Lee’s rock voice soaring over the majestic chord progressions. (

Lifeson throws in another mature and impressive solo at 4.00. Once again, |

he doesn’t over-reach or try to play an inappropriate phrase or fill. There is a

real skill in playing a solo that works for the song, and the guitarist is already j

demonstrating his mastery of this art.

The mood quietens at 5.41 with a return to the acoustic introduction and

the pleasing addition of some clean electric guitar tones. Lee retains his rock {

voice for the final lyrics, backed by some tasteful bass and percussive fills.

The song comes to a close with a final chord and a cymbal swell.

‘In The End’ is, after ‘Rivendell’, the most straightforward song on the |

album, but this does not diminish its power and effect. The dynamic contrasts

are effective, nobody is overplaying, and the song just rides out on its own

momentum, providing an effective closer to a second ‘debut’, which, in the |

main, promises much with the formation of the classic lineup.

With this track, Rush are presenting another stripped-down version of their _

compositional talents, and the song does not suffer one iota from such

simplicity. The song is another demonstration of the breadth of talent and |

ambition within the band. ‘In The End’ has an epic quality to it, but it is not |

trying to ape ‘By-Tor’s complexity; it is a simple statement delivered with

concise and consummate musicianship. This ‘new’ Rush could clearly write

and play in a wide variety of styles within the heavy rock genre, and it was

clear that this was only the beginning. They could go in whatever direction

they wanted. So they did.

In Contents Under Pressure, Neil had his own recollections of this period:

We just played what we liked. We were always that organic, and still are, through all those changes. There was no ‘Let’s synthesise these two styles; if we take that element and combine it with this element, we’ll have something new.’ It was nothing like that. We were never that self-aware, let alone that calculating. It was simply an organic response to playing what we liked. We liked to play loud and energetically, and this new, complicated, sophisticated approach appealed as well....end excerpt

Rush 1973 to 1982: Every Album, Every Song