|

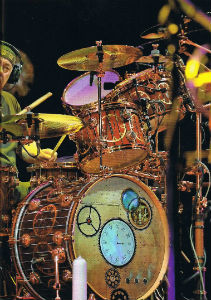

Part Two Rhythm Magazine April 2014 Words: Neil Peart Photos: Joby Sessions |

Click Any Image to Enlarge

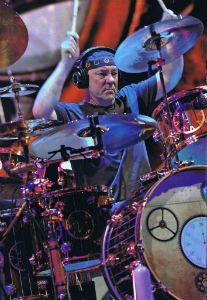

In part 2 of his insightful exploration of drum soloing, Neil Peart breaks down another of his Rush solos,

reveals his soloing influences and considers the future of the drum solo

This month, I will refer specifically to the arrangement that I happened to deliver on the night the DVD was filmed [Rush's new DVD, Clockwork Angels Tour]. In the tour's progress, these elements often appeared in different orders (listening back to this rendition now, I am gratified that the entire solo evolved a great deal during the remaining 40-or-so shows of the tour), but for our purposes, we'll consider this 'the one.'

By the time I had performed that solo a few dozen times, a natural series of 'movements' emerged from that free approach - a dynamic arrangement that seemed 'right.' I did not resist that evolution. It remained true to the spirit of improvisation, as each element within the movements was deliberately not allowed to become fixed. For example, when I went to the snares-off section over the waltz-time, I would be careful to begin the torn work in different areas of the kit every night. In every section of the solo, I would aim to keep transitions into and out of every pattern that might repeat as varied as I could.

An ending to a story, or a drum solo, is key, but at first I let that just 'happen' as well. Eventually it became clear that the flurry of hands and feet with cymbal accents was the ultimate climax - for me, and for the audience.

The axiom might be, 'If nothing works better, go with it.' (Even a drummer can sometimes see a no-brainer.)

However, it brings up a critical point. Like that climax, in other sections I would sometimes stumble across a rhythmic pattern that really excited the audience, and I would hear and feel their response. I liked that it happened naturally, but just on principle, to preserve that spirit, I refused to let it become a 'device'. It might seem irresistible to return to that pattern again, but not every night, and never the same way.

Some might feel there is nothing wrong with stringing together a series of such 'devices' (not to say 'tricks') that always work for the audience - you're supposed to be entertaining them, after all - and some performers would be happy with that result. Such methods are obviously how the formulaic arrangements of pop and country songs are assembled. But that seems to me a shallow pursuit. As my bandmate Geddy once said about the idea of songs having 'hooks', 'We are not trying to catch fish.'

And that, duh, is why drum solos almost never appear in pop and country concerts. Not 'part of the formula'. And notice that modern pop songs almost never have a single real drum in them, yet in concert, they always have a real drummer. For the dynamics, the excitement, the action of it all. They still need us.

Me, I want to tell a story, not just perform a schtick, so I have to be careful about those tricks. Some of them are just fun, like the stick tosses, and don't affect the music, or the 'purity of intent'. That's what has to be guarded.

Funny thing about the stick-throwing. I heard of such juggling feats as a kid, told about big-band drummers like Sonny Payne. A good story about Buddy Rich, who loved Sonny (he called him 'Funny' Payne), watching him play in the Count Basie band with my late teacher Freddie Gruber. As Sonny twirled and tossed sticks around and caught them, Buddy leaned over to Freddie and growled, 'He better be careful - he might hit something.' I also heard that the Rascals' drummer Dino DaneIli performed such tricks, but I never saw it done.

When Golden Earring opened for us in the early '80s, I saw Cesar Zuiderwijk doing it, and thought it was cool. So immediately (and shamelessly), I started copying him. It was simply fun to try to do, and always risky. At best, after 30 years, I manage to catch nine out of 10, but still, some of them just 'get away'. When the stick is in the air, the audience seems to share the tension with me: "Will he catch it?" If I do, they are as relieved as I am.

I always used to think there must be some trick to it, like jugglers and magicians have, and that probably guys like Sonny Payne could do it perfectly every time. Then Terry Bozzio directed me to a wonderful film of the Basie band playing in Sweden, and Sonny was dropping sticks all over the place. But oh, when he "hit something" - then it was sweet perfection.

'THE PERCUSSOR (I) - BINARY LOVE SONG (II) - STEAMBANGER'S BALL'

The main title 'The Percussor' derives from the novelisation of the Clockwork Angels story. Author Kevin J Anderson envisioned a clockwork drummer - 'The Percussor' - that began a hypnotic performance, then dropped a stick, and flew to pieces. (That was one of the few scenes in the novel I contributed to directly - I could relate!)

The subtitle, 'Binary Love Theme', comes from my motorcycle-riding partner, Michael, who is a computer geek who likes to try to insult me. (And those are his good qualities.)

During my pre-tour rehearsals, drum tech Lorne 'Gump' Wheaton put up a set of the new generation of V-Drums beside my main kit. Between bashes on the 'real' drums, I would experiment with their capabilities. A number of the programmed drumsets, from traditional to unearthly, were fun to play with, but I kept coming back to this one, 'Melodious'. I could play on it for hours.

As with previously-described electronic effects, every note in this solo is played. The difference is that on some of the pads (hi-hat, snare, ride, cymbal and bell), each strike would be a different note in an arpeggio. The crash cymbals were sustained minor chords, while other pads triggered percussion samples. The four toms were fixed piano notes, which I asked Jim Burgess to modify - adding a slight delay, so they were more like plucked harp notes. Playing on my 'back kit' for this, I could still reach some of the acoustic kit, like floor toms, piccolo snare, and cowbells, and they are incorporated into these pieces.

The 'Binary Love Theme' steps through a series of movements, everything improvised, or grown out of improvisation. The basic progression on this example is from waltz to 4/4, then to 7/8, but I even played with that juxtaposition from night to night.

Incidentally, quite a lot of paradiddle sticking is employed to achieve certain combinations of rhythm and melody. A reminder to practise those rudiments.

Second section with rhythmic ostinato and cowbells, 'block' sounds and other-worldly hits - steampunk effects - into xaxado (but electro) bass drum again... so melodic but still driving...

For this Jim Burgess and I selected an array of 'pre-electronic' industrial sounds. Metal sheets and iron boilers, steam release valves, anvils, sledgehammers, white noise, and sonar blips. Improvised patterns build to a repeating theme, which cues the video operator, Dave Davidian, to start the accompanying 'Percussor' film.

That is not 'done to click', but is a cooperation between Dave and me - his timing, and my tempo control, you might say.

As a general thing, I use very few 'click' cues in our live show - and then only for sequenced passages that are too legato or vague to keep in sync with, and sometimes for the sake of the string players. (Holding together 11 musicians is exponentially more complicated than when we are just three!)

At the end, where the Percussor goes to pieces, I try to portray that with a 'deconstruction' of the pattern, then end with a couple of steam-train whistles. Because... well, just because...

THE FUTURE OF THE SOLO

Finally, I have been asked about the 'future' of the drum solo. As mentioned, these days it is absent from the 'mainstream' of popular music, but I would venture that has been so since the dawn of recorded music. Jazz has always embraced self-expression, freedom, and virtuosity, and that has not changed. Some rock musicians have also aspired to those values, but in the final analysis, it is up to the audience.

The popularity of more adventurous music ebbs and flows, but does seem to endure. Perhaps in these times even the word 'progressive' has evolved from admired, to despised, to mildly respected.

Certainly it has always been true that drum solos are more exciting in concert than on record. Again, drummers have a visual thing going on - what is nowadays called 'optics'. If it is left up to the audience, I believe drum solos will endure.

Because for almost a hundred years now, through countless style changes in hair, clothes, and music, people have been excited by a drummer playing something that excites him or her.

It's in our very cells. Usually...

"But before Alice could answer him, the drums began. Where the noise came from, she couldn't make out: the air seemed full of it, and it rang through and through her head till she felt quite deafened. She started to her feet and sprang across the little brook in her terror, and had just time to see the Lion and the Unicorn rise to their feet, with angry looks at being interrupted in their feast, before she dropped to her knees, and put her hands over her ears, vainly trying to shut out the dreadful uproar.

"If THAT doesn't "drum them out of town", she thought to herself, 'nothing ever will!'" (From Through the Looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll.)

12 Essential Drum Albums by Jason Bittner

With 'Shadows Fall', Jason has built a reputation as one of metal's finest players.

Here he breaks down his most influential albums

#1 Rush Exit...Stage Left (1981)

"The reason I picked Exit...Stage Left is because it's impossible to pick just one Rush studio album. Rush are my favourite band, and Neil Peart is my favourite drummer. I can't possibly sum up the band in one record, but I can say that Exit... epitomises a period in time when Neil was most influential in my life.

"When I was a freshman and sophomore in high school, I would come home every day and play along to this record - at least to the best of my ability. I set drums up so they were just like Neil's, having everything as exact as I could - the same everything. It was that important to me. I could go on about how awesome the record is. The drum solo is still one of my favourites ever. It's definitely my favourite Peart solo. The drum sound on the record is amazing, too, which is saying something because sometimes the sound on live records can be lacking. Okay, if I had to pick a favourite Rush studio album it'd be Moving Pictures - a brilliant album all the way around."