|

What Was I Thinking?” Record Collector Magazine February 2024 by Joel McIver |

have offered fans new insights into this Canadian rock institution and their bassist. Now he answers our questions.

Frontman of the much-missed Rush, child of Holocaust survivors, veteran of

40-plus years in progressive rock, self-confessed germophobe and details

obsessive – and arguably the Greatest Living Canadian – there’s a lot

for Geddy Lee, 70, to talk about. Fortunately, he’s been able to squeeze it all

into his new autobiography, My Effin’ Life, in which he explores the perils

of fame, the pleasures of retirement, and an unexpected dalliance with Peruvian

marching powder. Asked to name Rush’s best album by Joel McIver,

he warns, “Millions of fans are going to disagree with me on this...”

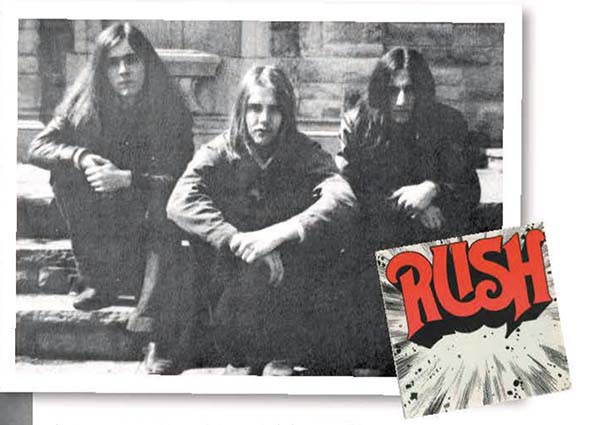

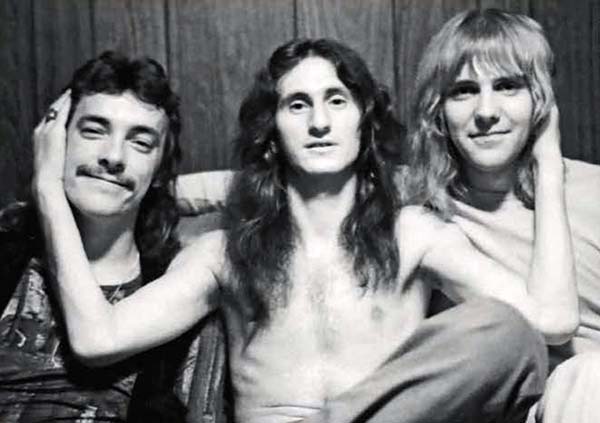

There has never been another band

quite like Rush, who formed in

1968 and blew people’s minds

worldwide for the next 47 years. An

intellectual trio of master musicians

who delivered high-fantasy flights

of fancy in the 70s, ascended synth-and riffheavy

commercial heights in the 80s and

settled neatly into classic rock iconhood in

the 90s, they represented the ultimate

triumph of mind over marketing. With a

very Canadian reputation for polite

eccentricity, the trio – Geddy Lee (vocals,

bass and keyboards), Alex Lifeson (guitar)

and Neil Peart (drums) – should, by rights,

have never made it big, but in fact they

were huge, especially at the triumphant

back end of their careers, when they played

arena tours worldwide.

There has never been another band

quite like Rush, who formed in

1968 and blew people’s minds

worldwide for the next 47 years. An

intellectual trio of master musicians

who delivered high-fantasy flights

of fancy in the 70s, ascended synth-and riffheavy

commercial heights in the 80s and

settled neatly into classic rock iconhood in

the 90s, they represented the ultimate

triumph of mind over marketing. With a

very Canadian reputation for polite

eccentricity, the trio – Geddy Lee (vocals,

bass and keyboards), Alex Lifeson (guitar)

and Neil Peart (drums) – should, by rights,

have never made it big, but in fact they

were huge, especially at the triumphant

back end of their careers, when they played

arena tours worldwide.

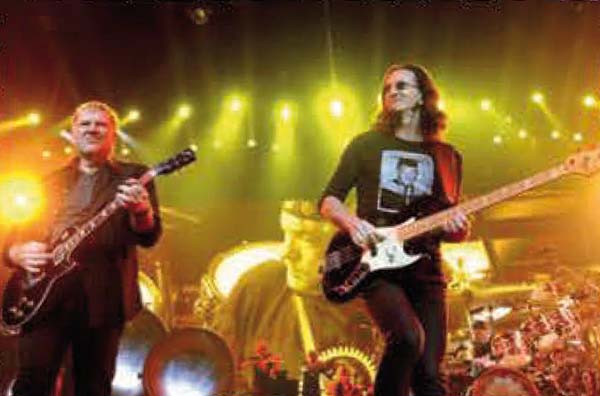

If you caught them on one of those

dates, you’ll recall the staggering scale of

both the production and the songs. Even as

a mere trio, Rush made planet-sized music,

with Lee steering the show through their big

hits Tom Sawyer, YYZ, Limelight and The

Spirit Of Radio with a benevolent smile,

uttering batlike vocals of extraordinarily

high frequency: famously, US alt-rockers

Pavement saw fit to discuss his unique pipes

in their 1997 song Stereo.

If you never saw Rush live, you’re out

of luck, because they ceased touring in

2015 and Peart died at the age of 67 five

years later, to the widespread shock and

grief of the group’s enormous fanbase. This

marked the end of Rush as we knew it:

more than just a rock drummer, Peart was a

deep thinker and lyricist who had suffered

the losses of his first wife and daughter,

causing him to step away from Rush from

1998 to 2002.

Lee and Lifeson have essentially been

retired for the best part of a decade now, but

hopes that they would play together again

never went away. This eventually came to

pass in September 2022, when the two

played at the Taylor Hawkins Tribute

Concerts in London and Los Angeles: check

YouTube for the massive reaction from the

crowd – and fellow musicians – at either

event. An earlier, equally enthusiastic

response had greeted Lee when he played

with his heroes Yes in 2017, on the occasion

of their induction into the Rock And Roll

Hall Of Fame.

Still, Lee evidently doesn’t want or need

to be a full-time musician anymore. He has

other matters on his mind, writing The Big

Beautiful Book Of Bass in 2018 and now

publishing a full-blown autobiography, My

Effin’ Life. He’s also a photographer and

wine expert, and clearly has plenty to occupy

himself. Yet still, in the wake of his recent

spoken-word tour, rumours havs spread far

and wide that he and Lifeson may reconnect

for (whisper it) something new from Rush.

Time, RC feels, to ask him some of

the big questions…

Are you pleased with the way My Effin’ Life turned out, Geddy?

Yeah, I think I am. When I start doing

something, I have a tendency to get a bit

carried away – that seems to be in my

genetic makeup – and I wrote an awful lot

of words: the first version was 1,200 pages.

After we cut it down to a somewhat

reasonable size, although it’s still 500 pages,

I was like, “Holy shit – what was I

thinking? What the fuck was I talking

about in those other 700 pages?”

Yeah, I think I am. When I start doing

something, I have a tendency to get a bit

carried away – that seems to be in my

genetic makeup – and I wrote an awful lot

of words: the first version was 1,200 pages.

After we cut it down to a somewhat

reasonable size, although it’s still 500 pages,

I was like, “Holy shit – what was I

thinking? What the fuck was I talking

about in those other 700 pages?”

And what’s the answer?

I guess you could call it every boring detail

[laughs]. I had stories about my travels, I

had stories about my hobbies and my

indulgences, and a lot more personal

adventures and family stuff. In the end it

was pared back, and rightly so – I have no

problem with that. They did a good job.

You were born Gershon Eliezer Weinrib in Toronto in 1953. Your parents, Moishe and Malka Weinrib, were Polish immigrants who had narrowly survived Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen as teenagers: you recount their experiences in painful detail in the book. How did you research this period of history?

I took a lot of time over it. I had a lot of tapes

that I had recorded of my mother, particularly

in 1995 when my sister, my brother and I

accompanied her back to Germany for the 50th anniversary of her liberation from Belsen.

We followed up that trip by going to Poland

and visiting her hometown. During that time,

my brother and I were recording her while she

spoke and getting her, while she was in the heat

of the moment, to clarify her stories, because

she did have a tendency to tell the same story

in a few different ways. There were also a

couple of books that I found incredibly

valuable, including Remembering Survival by

Professor Christopher Browning, who talks

about the same phenomenon.

What were the primary challenges there?

You’re talking about traumatic experiences

that happened to teenagers, and here they are

50 or 60 years later, trying to recall the stories,

and yet they’ve told each other those stories so

many times that the facts kind of

blend. I set about reading a lot of

stories by other survivors, and

there are some very heartfelt and

detailed accounts from the same

village that my mother came

from. There’s also the marvellous

collection of interviews by the

Shoah Foundation. I found

members of my family among

them, amazingly. I was able to

cross-reference a lot of what they

had gone through, so what I

ended up with is pretty close to

the truth, I think. Obviously, I

wasn’t there, so it’s based on the

information I was able to glean

from all these different accounts.

There were some people at the

Polish Museum in Warsaw who offered to

help: they sent some incredible documents,

including my grandfather’s arrest and

deportation warrants. That was just jawdropping.

I wanted to get it right, and I

wanted it to be my telling of their stories, so

I tried to do as much as I could.

You’re talking about traumatic experiences

that happened to teenagers, and here they are

50 or 60 years later, trying to recall the stories,

and yet they’ve told each other those stories so

many times that the facts kind of

blend. I set about reading a lot of

stories by other survivors, and

there are some very heartfelt and

detailed accounts from the same

village that my mother came

from. There’s also the marvellous

collection of interviews by the

Shoah Foundation. I found

members of my family among

them, amazingly. I was able to

cross-reference a lot of what they

had gone through, so what I

ended up with is pretty close to

the truth, I think. Obviously, I

wasn’t there, so it’s based on the

information I was able to glean

from all these different accounts.

There were some people at the

Polish Museum in Warsaw who offered to

help: they sent some incredible documents,

including my grandfather’s arrest and

deportation warrants. That was just jawdropping.

I wanted to get it right, and I

wanted it to be my telling of their stories, so

I tried to do as much as I could.

This sounds like a gruelling experience.

At times it was. I tried to put myself in the

guise of a historian, and to separate myself

from it, even though it was my own family

members. In Professor Browning’s book,

there is a story about the day that the train

left the Polish town of Starachowice for

Auschwitz, and he’s quoting my cousin. I

could not believe it. That was quite a heavy

moment for me – to see my own family there.

Those moments were very

impactful, and writing the

book was both therapeutic

and cathartic.

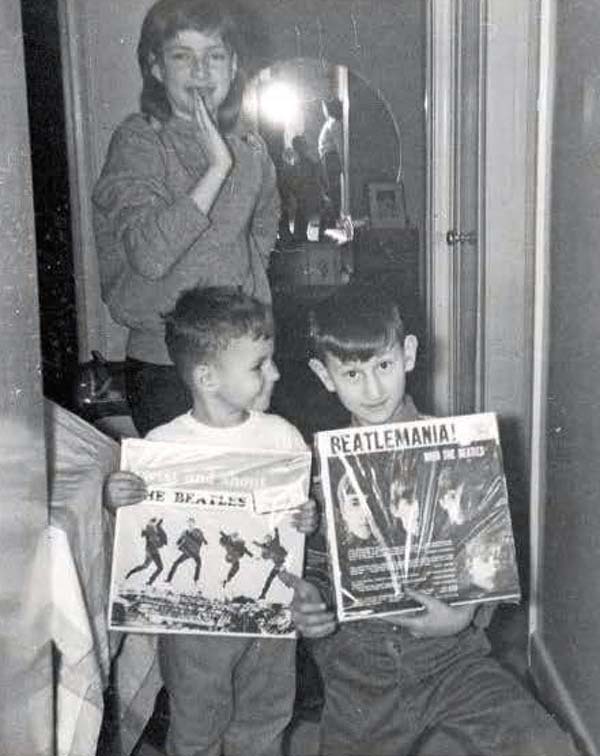

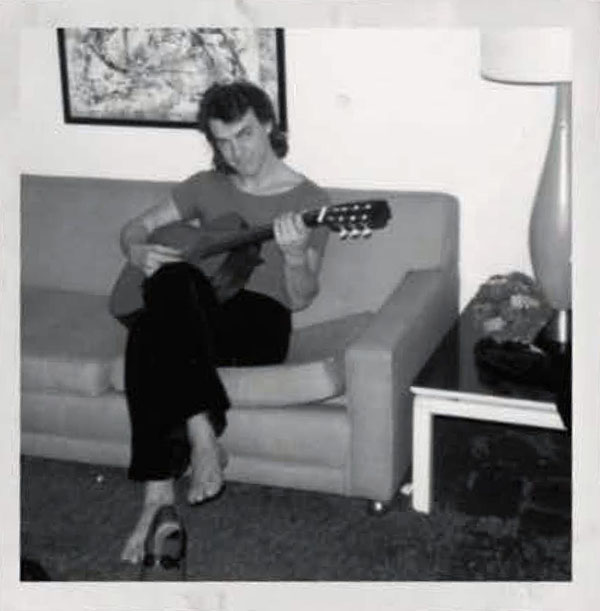

Your father died in 1965, when you were 12. Given that, it seems foolish to ask if you had a happy childhood.

I don’t think I was a

particularly happy child,

although in my very earliest

memories I was fairly happy.

I was a quiet kid, but I did

have a bit of a goofy side.

My brother once showed

me some old film footage

that my dad took, and in

the films, I’m always hogging the camera.

I never thought of myself as such a ham, but

I clearly had a hammy streak. That was

revelatory when I wrote the book, because I’d

always had a mistaken impression of myself as

a child. I thought I was this quiet, nerdy kid,

but time and time again, examining my

actions as a young child and then after my

dad passed away and I got into music, I was

obviously acting with great purpose. That

doesn’t come from a shy, nerdy kid: it comes

from somebody that wants something out of

life. That was a surprise, and I learned a lot

more about myself than I bargained for.

I don’t think I was a

particularly happy child,

although in my very earliest

memories I was fairly happy.

I was a quiet kid, but I did

have a bit of a goofy side.

My brother once showed

me some old film footage

that my dad took, and in

the films, I’m always hogging the camera.

I never thought of myself as such a ham, but

I clearly had a hammy streak. That was

revelatory when I wrote the book, because I’d

always had a mistaken impression of myself as

a child. I thought I was this quiet, nerdy kid,

but time and time again, examining my

actions as a young child and then after my

dad passed away and I got into music, I was

obviously acting with great purpose. That

doesn’t come from a shy, nerdy kid: it comes

from somebody that wants something out of

life. That was a surprise, and I learned a lot

more about myself than I bargained for.

You’ve experienced frequent epiphanies, or moments of acute perception, since childhood. What are they like?

It’s a sudden, acute sense of everything around

you. You’re struck by your own existence. It

feels a little bit surreal, so you ask yourself, “Is

this actually happening, or am I having an

acid flashback?” I’ve always had those in my

life. They’ve been described as moments of

existential angst, and maybe that’s what they

are, or maybe it’s just awareness. Sometimes

you go through your day and you’re thinking

shit and you’re doing stuff, and then you stop

and take everything in. As a kid, these

moments could be very overwhelming.

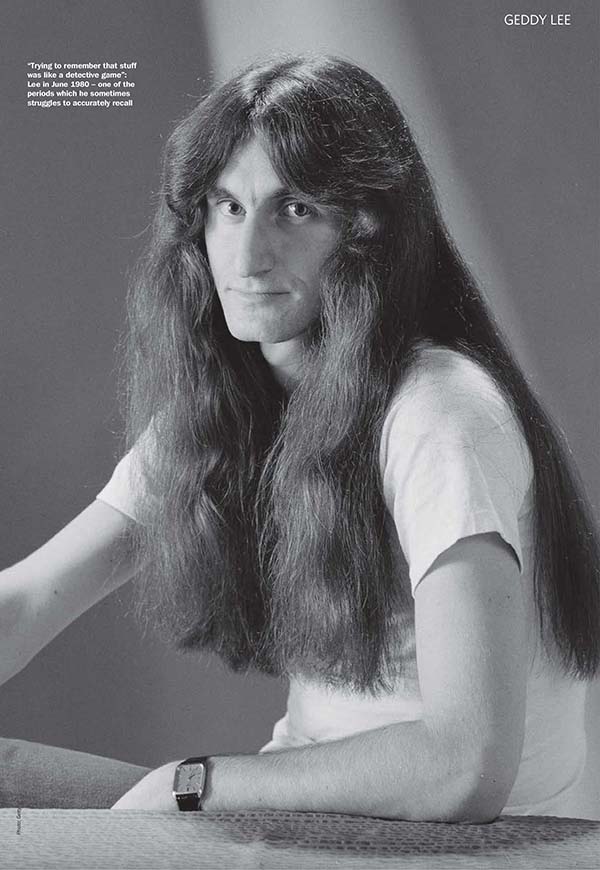

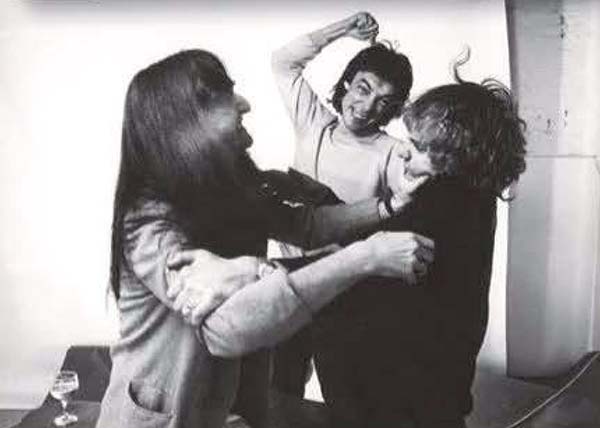

You joined Rush in 1968, and the fun began in earnest.

Yeah, for sure. The most fun I had writing this

book was dredging up the touring stories about

hanging out with my pals Alex and Neil and

remembering everything we went through. In

particular, talking about the 70s and 80s was a

blast for me. Trying to remember all that stuff

was like a detective game, figuring out where

you were and putting each year back together

in your memory. Some of it just falls out of

memory, so I’d call Alex every once in a while

and say, “Hey Al, do you remember that gig

we did?” or “Do you remember that incident?”

Some things he would remember exactly, and I

could have completely forgotten them.

And then other things, he was a total blank

on. It was a very interesting study on the frailty

of memory.

Is it correct to say that Rush didn’t make any money until 1978?

That’s not 100 per cent accurate. We

weren’t skint, and we had homes and nice

cars, but I always say that fame comes long

before profit. Truth be told, we weren’t very

bright when it came to money. We always

wanted to put it back into the show and

make the show better; for example if we

wanted a new crew guy, or if we wanted to

do a new kind of special effect, so we had a

hard time balancing the books in the early

days, for sure.

That’s not 100 per cent accurate. We

weren’t skint, and we had homes and nice

cars, but I always say that fame comes long

before profit. Truth be told, we weren’t very

bright when it came to money. We always

wanted to put it back into the show and

make the show better; for example if we

wanted a new crew guy, or if we wanted to

do a new kind of special effect, so we had a

hard time balancing the books in the early

days, for sure.

In the book, you reveal that you got into cocaine in the 80s. I didn’t expect that.

Yep. Someone else expressed that same

reaction recently, and asked, “Why didn’t

anyone know that?”, which got me thinking.

Because we were a progressive rock band

from Canada that didn’t have any big hit

singles, there was really no journalistic or

pop culture spotlight on us at all. We

plodded along in relative obscurity, in a way.

We had our fanbase, but there were no

journalists that wanted to come and hang

out with us for five days, like we were Led

Zeppelin. There was no sexy lifestyle that

they were attracted to, so we could get

fucked up in private without anybody really

knowing what we were up to. Me and my

buddies, we did like to smoke pot in the

early days, and we did try other things along

the way, including a lot of acid when we

were really young, but we were a part of the

60s drug culture, and we were a product of

that. Some of those drugs got the best of

me, but fortunately we survived them.

Do you still indulge?

No, I don’t do drugs. Wine is my drug now.

Moving Pictures (1981) album was a commercial high-point for Rush, but you didn’t enjoy fame, and you hated it when fans became too obsessed. Did it ever occur to you that you’re too sensible to be a rock star?

Not in the way that you put it, but there

are things about the lifestyle – now that I’ve

been sitting here for eight years, since our

last tour – that I don’t miss. I don’t miss

the crowd roar... okay, maybe I miss that a

little bit. What I do miss is the job, and

that beautiful moment when you’re playing

well, and you look across the stage and your

partners are playing well, and you’re lost in

that moment. That is the best thing ever.

That’s what I miss.

Not in the way that you put it, but there

are things about the lifestyle – now that I’ve

been sitting here for eight years, since our

last tour – that I don’t miss. I don’t miss

the crowd roar... okay, maybe I miss that a

little bit. What I do miss is the job, and

that beautiful moment when you’re playing

well, and you look across the stage and your

partners are playing well, and you’re lost in

that moment. That is the best thing ever.

That’s what I miss.

There’s a clip on YouTube of Rush playing the 1981 song YYZ in Brazil, and the caption is, “Only this band could make 60,000 fans sing along to an instrumental”.

[laughs] They were amazing! The Brazilians

wrote their own parts. It was incredible. I do

miss that part. The first time that ever

happened was at the Apollo in Glasgow, and

I had chills from that and so did my

partners, I can tell you. So, I’m not going to

say that it’s not a great feeling to be onstage

and have people throwing a lot of love at

you. I would be lying if I said that. But it’s

not something I miss.

You often refer in the book to the band impacting on your marriage. I imagine it’s impossible to be both a touring musician and a present partner or father.

It’s near-impossible, for sure, and there’s

damage, which is usually suffered by someone

other than yourself. I know so many musicians

whose marriages have failed, or come close to

failing, or whose children have been neglected,

and I have guilt about that with my own kids.

Work, and my obsessive nature, means that I

get sucked into it, and I didn’t pay enough

attention to them. That’s something that I’ve

tried to correct over the last 20 years of my life,

and I know that the other guys were also very

aware of that.

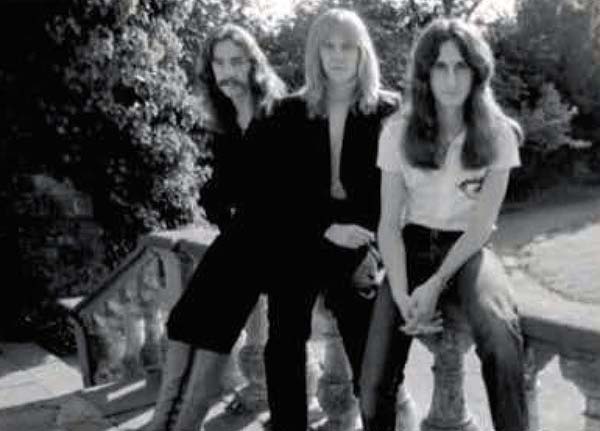

There seemed to be a transition point in the early 2000s when Rush relaxed and started having fun, playing giant arenas and having crazy props onstage and so on.

There definitely was. It began with Neil

coming back to the band and touring the

Vapor Trails album in 2002. It felt like a

second lease of life. I never thought Neil would

get through [the losses of his wife and

daughter] and want to play again, but here we

were onstage, after that incredibly difficult

record to make, and the atmosphere felt so

easy. There was an easiness between us and a

clear love between us, and a willingness to not

worry about anything else but playing our

asses off and trying to make each other laugh.

From that point until the end of our career,

that’s all we tried to do. Write well, play well

and make each other laugh.

There definitely was. It began with Neil

coming back to the band and touring the

Vapor Trails album in 2002. It felt like a

second lease of life. I never thought Neil would

get through [the losses of his wife and

daughter] and want to play again, but here we

were onstage, after that incredibly difficult

record to make, and the atmosphere felt so

easy. There was an easiness between us and a

clear love between us, and a willingness to not

worry about anything else but playing our

asses off and trying to make each other laugh.

From that point until the end of our career,

that’s all we tried to do. Write well, play well

and make each other laugh.

As you see it, when was Rush on peak creative form?

I think with the Clockwork Angels album

(2012). Now, millions of fans would

disagree with that [laughs], but I think

there’s a maturity in the writing of that

album that was not possible at any other

time in our history. Some would point

immediately to Moving Pictures and say,

“That was your peak” and there’s an

argument to be made for that, but if you’re

asking me, it’s Clockwork Angels.

Performing with Yes at their Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame induction in 2017 must have felt good.

That was huge thrill for me to do that, I have

to say. It was an odd experience, showing up

to rehearsal and meeting the guys, because

we’d never met before. There were two Yeses

at the time, so it was a bit of an odd scene,

but nonetheless I was welcomed very warmly

and that made me feel great because their

music meant so much to me. Playing [the

1971 Yes hit] Roundabout was just about the

ultimate thrill. I woodshedded for that

moment, I can tell you – I didn’t want to

fuck it up.

Do promoters and other industry people ever suggest that Rush should recruit a new drummer and tour?

Constantly, and I appreciate it. I don’t belittle

it; I don’t dismiss it. When Alex and I played

the Taylor Hawkins Tribute concerts last

year, it was very good for us to do that. It was

nice to play those songs with other people,

and it was no disrespect to Neil at all. Those

songs are us, you know? They were him, but

they were also us, so to retake ownership of

those songs and to not be afraid of that

moment was huge, and very tempting to do

again. Previous to that, I’m not sure I could

make that claim. It was really thanks to the

incredible will and generosity of Dave Grohl,

the most superhuman being on the planet.

He gave us that opportunity: he wanted us

there, and he was so encouraging. He did

everything he could to make it as easy for us

to come back in that context, and he was very

cognisant. I remember having conversations

with him where he’d say, “Well, you can’t

play with just one drummer, because then

they’ll all say that it’s Rush 2.0.” I was like,

“Oh yeah – you’re right, Dave. How about

you be one of the drummers?”

He’d lost both Kurt Cobain and Taylor Hawkins, of course, so perhaps he understands the sensitivities better than most people.

He understands a lot. He’s a caring, sensitive,

incredibly giving person. His encouragement

brought us back to the stage, and it was in

honour of Taylor, of course, and in honour of

our own bandmate and pal Neil, but it was

more than that, and I think he knew that.

The Californian band Primus toured America last year, playing your 1977 album A Farewell To Kings in its entirety. Did you see the show?

Alex and I went when they came to Toronto

and sat at the side of the stage. It was weird for

us to watch, but suddenly I felt Alex’s hand on

my shoulder: he was proud to see that someone

cared so much about what we’d done that they

were willing to go out and pay tribute to it. It

was very sweet, and we love those guys so much.

They’re such great people and great players –

and it was great hearing Les [Claypool,

bandleader] try to sing my parts. He just did it

as himself, which was absolutely right. He made

it his own.

Alex and I went when they came to Toronto

and sat at the side of the stage. It was weird for

us to watch, but suddenly I felt Alex’s hand on

my shoulder: he was proud to see that someone

cared so much about what we’d done that they

were willing to go out and pay tribute to it. It

was very sweet, and we love those guys so much.

They’re such great people and great players –

and it was great hearing Les [Claypool,

bandleader] try to sing my parts. He just did it

as himself, which was absolutely right. He made

it his own.

You name a lot of people in your book who have either been good to you or have wronged you. Your exact words are, “I am a motherfucker who bears a grudge”. That’s an unusual degree of honesty.

[laughs] Well, that’s good, I guess. When I set

out to write this book, my co-writer Daniel

Richler said to me, “Are there any rules?” I said,

“Only one rule, which is that the only person I

should embarrass is myself.” I didn’t quite stick

to that, because there were a few times that I

could not resist embarrassing someone else, but

for the most part I tried to keep it to people that

impressed me or moved me, or to people I miss,

and the people I’ve lost. I’ve lost a lot of people,

and sometimes I wonder, “Is that normal?”

Sometimes it feels as though I’ve lost an

inordinate amount of people on a regular basis.

Part of the motivation to write is to try and

make sense of all of that to myself.

Have you achieved that goal?

Well, in bits. I think it was good for me.

Reviewing and paying homage to some of

these lost friends was good for me and good

for my heart.

You also mention being obsessed with details. Does that make you difficult to work with?

I don’t think I’m a difficult guy, but that’s me

talking. You’d have to ask the people who are

sitting beside me in the control room. There’s

probably more than one recording engineer

who would beg to differ, but I’ve managed to

remain friends with all the people I’ve worked

with, so I think that must say something about

my ability to be insistent, at times, but not

belittling or unfair. I’ve always put the

project first, not my own self or my own

wishes. Again, Alex might argue with that

from time to time [laughs]. But he still loves

me, so we’re all good.

Do you feel optimistic about the future?

I do, and I don’t think I could have said that

before this book, to be honest. That tells me

a lot about what the process has put me

through. I feel happier today than when I

started to write this book, and you have to

remember, I began it not very long after Neil

passed, so it was a very tough time. But here

we are, at the beginning of 2024, and I do

feel optimistic about the future, and excited

to see what’s around the corner.

Well, that’s the question that everyone will ask you – what’s next?

[laughs] Right! I don’t know. One thing I do

know is that I don’t want to plan my life too

far ahead. Another thing is that my life with

my wife comes first, so any other idea –

whether it’s musical or not – is subservient to

those decisions. Would I do a musical

project? Yes, I would. Will I? We’ll see. I’m

up for it, but there’s the task of promoting

this book, and once that’s out of the way, I

think there’ll be a clear view of some musical

endeavour that will draw me back in.

[laughs] Right! I don’t know. One thing I do

know is that I don’t want to plan my life too

far ahead. Another thing is that my life with

my wife comes first, so any other idea –

whether it’s musical or not – is subservient to

those decisions. Would I do a musical

project? Yes, I would. Will I? We’ll see. I’m

up for it, but there’s the task of promoting

this book, and once that’s out of the way, I

think there’ll be a clear view of some musical

endeavour that will draw me back in.

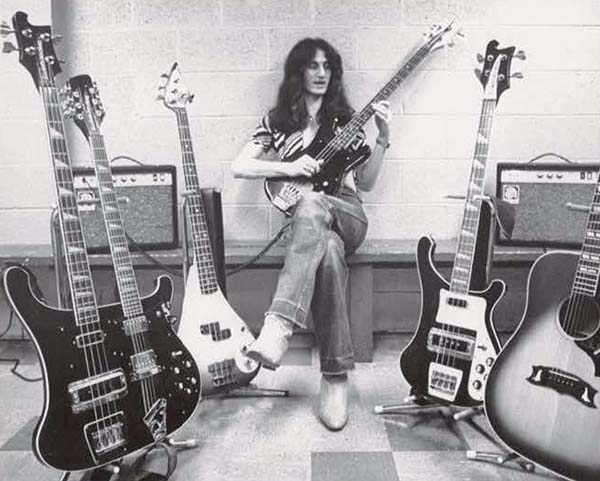

Are you good at doing nothing?

Pretty effin’ good at it [laughs]. I say that, but

my wife would vehemently argue that I’m

never doing nothing, because I’ve always got

a project on the go. I’ve just finished another

little book that I’ll save for another

conversation, and I have so many other ideas

for other types of book. I’m obsessive about

my bird photography: I have two years of

bird photographs that I haven’t sorted

through yet. And then there’s all those bass

guitars that are staring at me very guiltily,

saying, “What the fuck, man? What are we

doing here if you’re not gonna play us?” All

those things are begging for an answer, and I

have to attend to them.

It’s the burden of choice.

Yeah. But it’s kind of wonderful to have

things you want to do, and not all of them are

important in the big scheme of things. You

make them important by deciding that you’re

gonna spend time on them.

In the book, you seem to conclude that music and family are all we really have. Did I interpret that correctly?

You did. At the end of

the day, that’s what you

can hold close to you.

You know those are real.

Everything else seems so

ephemeral.

-| Click HERE for more Rush Biographies and Articles |-