|

(Preview) by Neil Peart © 2004 |

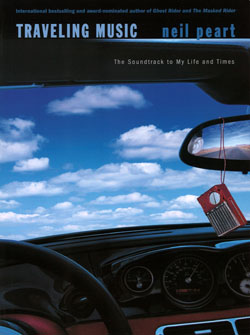

Click Any of the Following Images to Enlarge

In March 2003, Neil Peart, the international bestselling author of Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road, a haunting, critically acclaimed, and award-nominated memoir, was thinking about life's eternal "Now what?" questions.

The previous year, Peart, the lyricist and Hall of Fame drummer of the legendary rock band Rush, and his bandmates, Alex and Geddy, had released a bestselling album, Vapor Trails, and toured North, Central, and South America. Now he was enjoying some time at home in California with his wife, Carrie, but at the same time feeling an author's creative urge to write a new book, without knowing yet what it should be.

Needing time to think about book ideas and other "Now what?" questions, Peart decided to drive his new dream sports car, a BMW Z-8, on a six-day, 2,500-mile roundtrip journey to Big Bend National Park, in southwest Texas, and listen to "traveling music" all the way, by artists ranging from Frank Sinatra to Linkin Park, Miles Davis to Radiohead, Patsy Cline to Madonna.

As he drove and listened, he experienced the traveling essence of music itself, and the songs took him on voyages of memory, imagination, emotion, sensation - and when he reached Big Bend Park on the third day, creative inspiration: "A story could be written just around the music I've listened to on this trip."

Written with the most resonant distillation of words and rhythm, in the poetic sense of being suggestive of meaning, but allowing the reader's own music to create the soundtrack, Traveling Music is Peart's exhilarating, inspiring, appreciative celebration of excellence in the artists who inspired his own creative odyssey, from childhood to maturity - growing up in Ontario, Canada, living in London and the United States, and a near-lifetime of constant world travel as an adventurer, including a characteristic, month-long bicycle trip through West Africa and drumming with an African master. Through the power of his storytelling, all of the past and present comes alive, in music and memory, songs and stories.

NEIL PEART is an international bestselling author, and the lyricist and drummer for Rush, the most successful band in the history of Canadian rock music.

His previous book, Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road (2002), was chosen by The Writers' Trust of Canada as a Drainie-Taylor Biography Prize Finalist, because of its "exceptional merit" as one of the five best biographies of the year.

Peart's first book, The Masked Rider: Cycling in West Africa (1996), is a tale of high adventure and enormous stamina, one of the most memorable and demanding of his journeys to eleven African countries - his first bicycle tour through Cameroon.

For their achievements in music, Peart and his Rush bandmates have received the Order of Canada, the country's highest civilian award.

Forward:

For this music lover, the concept of "traveling music" evokes several responses. Listening to music while traveling, by one means or another, is the obvious association, and my life has provided plenty of that, in cars, airplanes, boats, bullet trains, subways, and tour buses.

Then there's the "inner radio," when every song I know seems to play in my head, as I perch on the saddle of a bicycle or motorcycle for long, long hours.

"Traveling music" can also be a job description. For thirty years I have made my living as a touring musician, playing drums with Rush in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia, and that has made for a lot of traveling, and a lot of music.

In my other job description with Rush, writing lyrics, I have used many references to modes of travel, from bicycle to boat, sports car to spaceship, airplane to astral projection. My lyrics for our song "The Spirit of Radio" celebrate the simple pleasure of listening to the radio while driving, and inspirations have also come from journeys, and places both exotic and everyday: East Africa in "Scars," West Africa in "Hand Over Fist," China in "Tai Shan," London and Manhattan in "The Camera Eye," small-town Canada and America in "Middletown Dreams."

Most of all, though, I think of "traveling music" as the essence of the music itself - where it takes me, in memory, imagination, and the realm of pure abstract sensation, washing over me in waves of emotion.

Since childhood, music has had the power to carry me away, and this is a song about some of the places it has carried me.

Traveling Music

Driving away to the east, and into the past

History recedes in my rear-view mirror

Carried on a wave of music down a desert road

Memory drumming at the heart of a factory town

Diving down into the wreck, searching for treasure

Skeletons and ghosts among the scattered diamonds

Buried with the songs and stories of a restless life

Memory drumming at the heart of a moving picture

All my life

I've been workin' them angels overtime

Riding and driving and working

So close to the edge

Workin' them angels -

Workin' them angels -

Workin' them angels -

Overtime

Memory drumming at the heart of an English winter

Memory drumming at the heart of an English winter

Filling my spirit with the wildest wish to fly

Taking the high road, into the Range of Light

Driving down the razor's edge between past and future

I turn up the music and smile, eyes on the road ahead

Carried on the songs and stories of vanished times

Memory drumming at the heart of an African village

All this time

I've been living like there's no tomorrow

Running and jumping and flying

With my imaginary net

Workin' them angels -

Workin' them angels -

Workin' them angels -

Overtime

Riding through the Range of Light to the wounded city

Taking the high road -

Into the Range of Light

Taking the high road -

Into the Range of Light

Repeat to fade ...

Table of Contents

Intro - "Play through the changes / pick up the tempo"

Verse One - "Driving away to the east, and into the past"

Chorus One - "Drumming at the heart of a factory town"

Verse Two - "Diving into the wreck, searching for treasure"

Chorus Two - "Drumming at the heart of a moving picture"

Verse Three - "Workin' them angels overtime"

Chorus Three - "Drumming at the heart of an English winter"

Middle Eight - "Filling my spirit with the wildest wish to fly"

Verse Four - "Driving down the razor's edge between past and future"

Chorus Four - "Drumming at the heart of an African village"

Verse Five - "Riding through the Range of Light to the wounded city"

Rideout - Repeat to fade ...

- Friedrich Nietzsche

The music I have written is

nothing compared to the music I have heard

- Ludwig van Beethoven

"Ooh, look at me, I'm Dave, I'm writing a book!

With all my thoughts in it! La la la!"

- Dave Eggers

Intro - Play through the changes / pick up the tempo

"Now what?"

All my life, those two little words have sparked me with curiosity, restlessness, and desire - an irresistible drive to do things, learn things, go places, seek more and always more, of everything there is to do and see and try. My need for action, exertion, challenge, for something to get excited about, in turn inspired my ambition to try to capture those experiences, in songs and stories, and share them.

When I was a teenager, sitting around the family dinner table with Mom, Dad, younger brother Danny and sisters Judy and Nancy, I would chafe inside my skin, wishing I just had something exciting to say - something I had done, or was going to do.

I guess I spent the rest of my life making sure I always had something to talk about at the family dinner table ... only I wouldn't be at the family dinner table. I'd be on tour with the band, or away making a record, or bicycling in China, or motorcycling in Tunisia. Then writing a book about it.

My daughter Selena seemed to have inherited some of that itch, for right up to her last summer, at age nineteen, she would climb out of the lake all sleek like a seal, flop on the dock beside me, splash some cold water over my sun-warmed back, look me in the eyes and say,

"Now what?"

I could only laugh, recognizing her own need for diversion, action, something to get excited about - something to talk about at the dinner table. However, in that summer of 1997, those little words came to bear an ominous weight, the menace of imminent tragedy. Selena would not live to find out "now what?"

For a while there, in 1997 and 1998, when everything was being taken away from me - my daughter, my wife, my dog, my best friend, everything I loved and believed in - my own "now what?" became less of an itch and more of a hemorrhage, more like Dorothy Parker's, "What fresh hell is this?"

But on I went, down that healing road, thinking, "something will come up," and as life would have it, something did. In fact, a lot of things came up: a journey to new love with Carrie, new home in California, and because of those unexpected miracles, a new lease on life and work. Back on the high road.

By 2001 I was writing lyrics and playing drums on a new record, Vapor Trails, with Rush, writing a book about that terrible part of my life, Ghost Rider, and spending most of 2002 traveling and performing in Rush's 66-show tour of North America, Mexico, and Brazil, culminating with a final concert in Rio de Janeiro, in front of 40,000 people, that was filmed for a DVD called Rush in Rio.

Early in 2003, all that was behind me, and I was relieved to be taking a break at home, enjoying time with Carrie, relaxed and content in the rhythms of domestic life. I had no ambition to tackle anything more creative or demanding than cooking dinner.

That tranquility lasted for a serene couple of months, until early March, when Carrie started making plans to attend an all-female surf camp in Mexico (a Christmas present from her thoughtful husband). She was going to be away for five or six days, and wheels started turning in my brain about how I might use that solitary time. Before I knew it (literally, as so often happens, before I realized my creative unconscious had started spinning its daydreams), every aspect of my life was orbiting into a clockwork vortex around that eternal question:

"Now what?"

Verse One - Driving away to the east, and into the past

The Santa Ana winds came hissing back into the Los Angeles Basin that week, breathing their hot, dry rasp through what had once been the fishing village of Santa-Monica-by-the-Sea. The streets around us were littered with dry palm fronds and eucalyptus leaves, and the view from our upstairs terrace reached the distant blue Pacific through the line of California fan palms down along Ocean Boulevard. The incoming waves battled the contrary wind, as dotted whitecaps receded clear back to the long dark shadow of Santa Catalina Island, bisected horizontally by a brownish haze of smog.

More than three hundred years ago, the Yang-Na natives called the Los Angeles Basin "the valley of the smokes," referring to the fog trapped by those thermal inversions. And even then, wildfires sometimes raged across the savanna grasses in the dry season, creating prehistoric smog. Then and now, the air was usually clearer by the ocean, ruled and cooled by the prevailing sea breeze, but the Santa Ana's invaded from inland, carrying hot desert air over the San Gabriel Mountains, through the San Fernando Valley, all the while gathering airborne irritants from the whole metropolis and driving them right through Santa Monica, and on out to Catalina.

The Cahuilla Indians believed the Santa Ana's originated in a giant cave in the Mojave Desert that led directly to the lair of the Devil himself, and early Spanish arrivals picked up on that story and named those hot, dry winds the Vientos de Sanatanas, or Satan's winds. Later arrivals to Southern California were more concerned with Christian propriety and boosting real estate values in this earthly paradise, and the Chamber of Commerce issued a press release in the early 1900s: "In the interest of community, please refer to the winds as 'The Santa Ana Winds' in any and all subsequent publications."

Still, the devil winds were blamed by longtime Angelenos for effects both physical and psychological: Raymond Chandler wrote in Red Wind that when the Santa Ana's blow, "meek little wives feel the edge of their carving knife and study their husbands' necks." Modern-day urban myths associate the Santa Ana's with rising crime rates, freeway gun battles, wildfires, actors entering rehab, Hollywood couples divorcing, bands breaking up, irritated sinuses, and bad tempers all around.

As a recent immigrant from Canada, I had thought all that was local folklore (or just a regular day in L.A.), but I had only lived in Santa Monica for three years, and spent much of that time working with Rush in Toronto or touring in other cities. Now, though, in late March of 2003, I was feeling the effects of those abrasive winds on my sinuses, and my mood. Along with the brownish haze over the sea and my itchy nose, tension was in the air.

For one thing, there was a war on. The United States and Britain were just into the second week of the attack on Iraq, and no one knew what might happen. The smoke and mirrors of propaganda and the phantom menace of "weapons of mass destruction" had been paraded before us so much that a kind of contagious anxiety had been sown. Dire possibilities seemed to be on everyone's mind, and in every conversation. The chance of a chemical attack on Los Angeles seemed ... at least worth worrying about. When the war began, I had said to my wife, Carrie, "Let's go to Canada," where I still owned the house on the lake in Quebec, and still had friends and family in Toronto. However, now some mysterious disease called SARS was spreading from Asia to Canada, and people were dying, hospitals were closing, there was a travel advisory against Toronto; it was a bad scene there too.

Then there were the interior battles, and internal "travel advisories" - the "don't go there" areas. I had some serious personal and professional issues weighing on my mind - big questions and big choices to make.

Work, for one thing. After only a couple of months at home, and spending most of 2002 on the Vapor Trails tour, and all of 2001 writing and recording that album, I felt I was just catching my breath. But plans had to be made so far in advance. Recently the band's manager, Ray, had been entertaining (or torturing) me with various scenarios of recording and touring possibilities for the upcoming years, and I would have to give some answers soon. In 2004, the band would celebrate our thirtieth anniversary together, so we'd probably want to do something to commemorate that. A party, a cake, a fifty-city tour?

What about prose writing? With a stretch of free time ahead of me in 2003, I felt I wanted to get started on a writing project of some kind again, and friends were encouraging me to write more. But what did I want to write? (Now what?) Maybe try something different from the travel-writing style of my first two published books, The Masked Rider: Cycling in West Africa (1996) and Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road(2002). Some fiction? History?

I didn't know, but I was thinking about it.

There were a few half-finished traveling books in my files, narratives of journeys I'd taken through the early '90s and never had the time or drive to complete: the third of my African bicycle tours, of Mali, Senegal, and the Gambia; several motorcycle explorations around Newfoundland, Mexico, and North Africa; perhaps I should look at them again. Or, back in the fateful summer of '97, I had abandoned a narrative recounting the Rush Test for Echo tour, called American Echoes: Landscape with Drums, when my life was suddenly pulled out from under me by tragedy and loss. But I wasn't sure I wanted to take up that story again, or any of the old ones. Something new would be good, it seemed to me.

In another area of my mind (I picture little, self-contained clockwork mechanisms, slowly grinding through their particular subject of cogitation until they produce the answer, the "right thing to do"), I was thinking about the house on the lake, up in Quebec. Having lived in California for over three years now, I didn't get there much anymore, and yet when I did visit, it remained ineffably haunted to me, after the tragedies. (Selena and I would stand right there in the kitchen, arms over each other's shoulders. That terrible night Jackie and I got the news in this hallway, and Jackie fell to the floor right there. These were not happy memories to continually relive.) The Quebec property was large and the upkeep was high, and maybe I didn't need it anymore. Maybe it was time to say goodbye to that place, and to that time.

Another little clockwork mechanism in my head was working on the problem of our California home, which was feeling increasingly too small, especially in its lack of a writing space for me. A two-bedroom townhouse, with Carrie taking one of the bedrooms as an office to run her photography business as well as most of our lives, left only the loft above the kitchen, open to the rest of the house. I would find myself trying to write against the clatter and chatter of our Guatemalan housekeeper, Rosa, and one or another of her cousin-assistants, vacuum cleaner and dishwasher, ringing telephones, and our cheerfully-mad assistant, Jennifer, running upstairs, all apologetic, to use the fax and copy machine.

It seemed that my years of training at reading in a crowded dressing room had made me able to concentrate no matter what was going on, and it had already served me well in writing - much of Ghost Rider had been written and revised in a recording studio lounge, with Vapor Trails being mixed on the other side of the window, the other guys coming and going, talking, laughing, watching TV, and occasional breaks to approve final mixes. The work could certainly be done, it just took longer.

There were other things on my mind, too. So much percolating around my poor little brain; I needed some time to think.

It seemed like a good time to get out of town.

In early March, knowing Carrie was going to be away for those six days later in the month, I started browsing through the road atlas (the Book of Dreams), thinking of where I might go. My favorite destinations always tended to be the national parks of the American West, where I could combine the journey with some hiking, bird-watching, and general communing with nature. While living in California (and not away working), I often made overnight motorcycle trips to Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks in summer, or to Big Sur or Death Valley in winter, exploring the myriad of Southern California's backroads with my restless curiosity and love of motion (and giving Carrie some time to herself, too). With a little more time and the opportunity to cover more distance this time, my first inspiration had been to ride my motorcycle to Utah, and wander around the wonderful national parks in the southern-part of that state, Zion, Bryce Canyon, Arches, and Canyonlands.

However, a look at the online weather reports tarnished that idea. The overnight temperatures in Bryce Canyon and Moab were still in the twenties, Fahrenheit, and that meant icy roads. No good on a two-wheeler. Even Yosemite was still in the grip of winter, and the only national park in the American Southwest I could think of that might not be under snow was Big Bend. So, I thought, "go there."

I had passed through that area of Southwest Texas once before, by motorcycle, during the Rush Test for Echo tour, in late 1996, with my best friend and frequent riding partner, Brutus. That tour was the first time I attempted that novel method of traveling from show to show, with my own bus and a trailer full of motorcycles. During the previous two years, my friendship with Brutus had grown strong as we both became interested in long-distance motorcycling. Exploring the pleasures and excitements of motorcycle touring, and learning that we traveled well together, Brutus and I had ridden tens of thousands of miles around Eastern Canada, Western Canada, Mexico, and across Southern Europe, from Munich down through Austria, Italy, and by ferry to Sicily, and across the Mediterranean to Tunisia and the Sahara.

We developed a comfortable rhythm between us, of tight formation, lane position, relative speed, and overall pace. Apart from being an entertaining dinner companion, Brutus always wanted to get the most out of a day - he could carpe that diem like few people I ever met. On an early ride together, we were motorcycling from Quebec to Toronto, normally a six-hour journey on the four-lane highway. Brutus convinced me to try one of his "adventurous" routes across Central Ontario, along county roads and country lanes that constantly changed number or direction. When we finally arrived in Toronto, I mentioned to Brutus that it had taken us nine hours instead of six, and he said, "Yeah, but would you rather have fun for nine hours, or be bored for six?"

Elementary, my dear Brutus, and a lesson was learned that reinforced my own tendency to seek out the back roads. From then on, if there was a chance to make a journey I had to make into a journey I wanted to take, I would seek out the high road, the winding road, and make the most of that traveling time.

So, when I was making plans to take my motorcycle on the Test for Echo tour, I convinced Brutus to come along too, as my official "riding companion"(he didn't take much convincing). Credited in the tour book as "navigator," a big part of Brutus's job really did become the plotting of the routes every day, as we moved around the country. He made it his mission to seek out the most interesting roads and roadside attractions, and while I was onstage, thrashing and sweating under the lights, Brutus sat in the front lounge of the bus surrounded by maps, magnifying glass, tour books, and calculator. He worked out the most complicated, round about, scenic, untraveled routes possible - that would still get us to soundcheck on time.(From the beginning, I warned Brutus that I tended to get "anxious" on show days, especially about the time, and that if we did not arrive at the venue at least an hour early, we were late. To his credit, we never were.)

As the bus roared down the interstates of America, Brutus would tell Dave where to stop for the night, usually a rest area or truck stop near the back road he had chosen for the morning. Sometimes I would go to sleep as Dave sped through the night, then wake to my alarm clock and the steady drone of the generator, in a wonderfully stationary bus. There was never enough sleep, but we were determined to make the most of the day, and sometimes I crawled into my riding gear, unloaded the bikes and rode away - without even knowing where we were. If it happened to be my turn to lead (we alternated every fuel stop), Brutus would point me in the right direction, and give me a sheet of hand-written notes on road numbers, mileages, and town names. Riding off into the morning, I followed Brutus's clear directions on the map case in front of me, and gradually discovered my place in the world.

After a show in El Paso, Brutus and I slept on the bus while Dave drove us to a truck-stop near Marfa, Texas. We got up early the next morning, unloaded the bikes from the trailer, rode south to Presidio, and followed the Rio Grande to Lajitas for breakfast. (It's a measure of how Brutus and I lived on that tour, making the most of every minute and every mile, that so much could happen before breakfast. Especially on a day off, with no schedule, no soundcheck, and no anxious drummer to worry about.)

Just after Lajitas and Study Butte ("Stoody Beaut"), we entered Big Bend National Park, and crossed through a tiny fraction of it, on the fly. We cut north to Marathon, east to Langtry (made famous by Judge Roy Bean, "The Law West of the Pecos"), Comstock, and Del Rio, and north to Sonora. There we met up with Dave and the bus again, and wheeled the bikes back into the trailer in the gathering dark. (We always tried to avoid riding at night - it was more dangerous, and we couldn't see the point of riding through scenery we couldn't see.) I remember falling asleep almost immediately on the couch in the front lounge, as Dave drove us on to the hotel in Austin, for the next night's show. Music played quietly from the Soul Train Hall of Fame CD (introduced to me by Selena, as it happened, in her teenage taste for "old school" R&B, echoing one of my own "first loves" in music).

On that tour, Brutus and I were up early every morning and rode a lotof miles, often 500 or so on a day off, and maybe 300 on a show day. In40,000 miles of motorcycling on that tour alone, through forty-seven states and several Canadian provinces, Brutus and I had many adventures together, in every kind of weather, from blistering heat to bitter cold and torrential rain, even snow and ice. A certain amount of pain and suffering kept things interesting, and made for good stories, but one thing we were constantly short of was sleep. On show days I used to squeeze in naps whenever I could, sometimes even setting my alarm clock for twenty minutes between dinner and pre-show warm-up.

So often our brief, rapid travels between shows were a kind of "research," checking out places that might be worth a later, more leisurely visit. Even that small taste of the Big Bend area had been impressive, as part of a continent-wide tour in which we had seen so much of America's scenic beauty. I retained a vague memory of majestic rock formations and wide desert spaces, canyons, bluffs, and mountains enclosed in a wide arc of the Rio Grande.

However, Big Bend National Park was 1,200 miles away from Los Angeles, on a fairly tedious, familiar interstate all the way (no time to take the high and winding road all that way). There were some areas of dodgy weather out that way too. Even by freeway, I'd have to ride two and a half long days to get to Big Bend, spend a day there, then turn around and make the same long slog home again. It didn't sound like a very appealing motorcycle trip, but it might be fun by car.

And not just any car. Early in 2003, I had become the proud owner of my longtime "dream car," a BMW Z-8, black with red interior (always my favorite combination). Driving that sleek, powerful two-seater through the Santa Monica Mountains, up Old Topanga Canyon to Mulholland Drive, and a longer trip up to Big Sur and back, revived the thrill I used to feel driving an open sports car (usually with music playing). Taken seriously, on a challenging road, driving could really feel like a sport,comparable to riding a motorcycle with adrenaline-fueled urgency.

Motorcycles had dominated my garage and travels for the past seven years, and bicycles before that, but I had loved cars since childhood. Mom says my first word was "car," and there's a photograph of me as a baby sitting behind the wheel of our '48 Pontiac, my tiny hands reaching up to the steering wheel and a beaming smile on my chubby little face. In my teenage years, drums and music had attracted all my attention (and all my money), so it was not until my early twenties that I bothered to get my driver's license - and only then after I'd already bought my first car. It was a 1969 MGB, an English roadster of traditional character (meaning it leaked oil and had an unreliable electrical system).

I had it painted purple (always celebrating my individuality), and I loved that car, even as it drained its oil, its battery, its radiator, my patience, and my meager wallet. After that came a Lotus Europa (a tiny, very low fiberglass "roller skate," about which my dad once asked, "You really prefer that to a real car?"), another MGB, and - once I became a little more successful- a couple of Mercedes SLS, two different Ferraris, a 308 GTS and a 365 GTB/4 Daytona, an MGA, and a 1947 MG-TC. At one point in the early'80s I had four cars at once, and decided that having too many cars, especially old ones, was more trouble than pleasure. I trimmed down to running just two, more "practical" machines, including a series of Audi Quattro GTS (the first all-wheel-drive sports car, a real bonus in Canadian winters), and a trio of successive Porsche 911S through the '90s.

I had always loved driving, and listening to music while I drove, especially on a long journey. In the unique zen-state of driving for hour after hour, music didn't just pass the time, it filled the time, with pleasure, stimulation, discovery, and memories. So, all things considered, the decision was made - I would drive to Big Bend. And listen to music all the way.

After dropping Carrie at the airport in the Audi wagon, I drove home and threw a small bag and my album of CDS in the trunk of the Z-8,checked the oil level and the tire pressures, then drove through Santa Monica to the freeway. Merging with the four lanes of eastbound traffic on Interstate 10, dense as always, I headed toward the towers of downtown Los Angeles.

Eastward and upwind, the view tended to be clearer than usual during the Santa Ana's, and behind the city, the San Gabriel's and the snowy peak of Mount San Antonio (commonly called Old Baldy Peak) dominated the background against the scoured blue sky. The "steel forest" of antennas high on Mount Wilson, near the observatory, was finely etched and glittering.

Early one morning, a year or two before, I had ridden my motorcycle up the Angeles Crest Highway from Pasadena and stood looking down from Mount Wilson just after sunrise. The morning was clear all the way out to the Pacific, and the landscape of the Los Angeles Basin seemed dominated by green, even though I knew those valleys were actually floored in wall-to-wall carpets of suburbs and freeways, broken only by occasional clusters of tall buildings. From my high vantage point, I looked south and west and tried to identify the major crossroads of the city, from San Bernardino to the San Fernando Valley, from the Downtown to Century City. Overlooking it all from that high vantage, I had the sense that human history was thin and brief, and no matter what we tacked onto the land, it was nature that still ruled. This Basin could endure another ten thousand years, or it could shake to pieces in a few hours - that was an omnipresent dread that seemed to bother immigrants more than natives, for at least once a week I imagined the coming of the Big One, "What if it happened now? In this house? This office tower? This elevator?"

Most residents of Southern California seemed to be insulated by the "geological denial" described by geologist Eldridge Moore in John McPhee's Assembling California:

People look upon the natural world as if all motions of the past had set the stage for us and were now frozen. They look out on a scene like this and think, It was all made for us - even if the San Andreas Fault is at their feet. To imagine that turmoil is in the past and somehow we are now in a more stable time seems to be a psychological need.In Elna Bakker's natural history of the state, An Island Called California, she gave a wry twist to describing the action along the San Andreas Fault (one of dozens that riddle California),

The land west of the fault is moving north at a generalized rate of more than an inch a year, and at some time in the future Los Angeles will be where San Francisco is now, a thought not happily received by most residents of that city.Standing by the observatories at Mount Wilson that morning, I looked down at the constellations of life below me, and tried to imagine the great megalopolis of Los Angeles, what it had been, and how it had grown into today's sprawling mass of humanity, and the place I was now trying to call "home." In 1781, a Spanish supply station for Alta California was established down there, with almost more words in its name than people: El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles del Rio de Porciuncula - The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels by the River of a Little Portion. Whatever it was a little portion of, it was not lotus-land, but an arid chaparral surrounded by mountains, with no harbor, an unreliable river, and a climate that ranged from Mediterranean to monsoon. According to historian Marc Reisner in A Dangerous Place,during the brief rainy season, the nether reaches of the basin - now Long Beach, Culver City, Torrance, Carson, the South Bay cities - were vast marshlands covered with ducks and prowled by bears. (The last California brown bear, the state's symbol, was shot in 1922.)

By 1791 the pueblo boasted 139 settlers living in 29 adobes, surrounded by vast ranchos, like the Rancho Malibu and Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica (owned by Francisco Sepulveda), that gave their names to modern communities and boulevards (including my adopted home of Santa Monica). The Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas became Beverly Hills; the Mission San Fernando became the warren of communities in the San Fernando Valley; the Rancho Paso de Bartolo Viejo would become the Quaker settlement of Whittier, Carrie's home town. (Richard Nixon's too, and one of Carrie's first jobs as a student was at his one-time law office.)

By the 1840s, EI Pueblo de Nuestra Senora de Los Angeles del Rio de Porciuncula had swollen into a rough cow-town, violent and deadly (averaging a killing a day), a place Reisner described as "a filthy, drowsy, suppurating dunghole, a social meltdown of Mexicans, Indians, Americans, various Europeans, Hawaiians, and a respectable number of freed or escaped slaves. Among its vernacular street names were..." words this sensitive soul blushes to write: the N-word Alley, and the female-Cword Lane. In any case, when the gold rush struck Northern California in1849, the population of Los Angeles declined from 6,000 to 1,600 in just one year, as everyone who felt able went north in search of instant riches.

(Interesting to note that by the end of the Civil War, $785 million in gold had been mined in California, making the crucial difference by delivering five or six million dollars a month to the money men of New York and keeping the Union solvent.)

By 1884 the population of Los Angeles had rebounded to 12,000, and it was then that the great land rush began, with boosterism, speculation, development, and outright fraud swelling the population to 100,000 in less than three years, and multiplying land values beyond all reason. The banks eventually pulled the plug, and the boom collapsed; suddenly the trains were arriving empty, and leaving full.

The famed naturalist John Muir visited in 1887, and wrote in his journal, "An hour's ride over stretches of bare, brown plain, and through cornfields and orange groves, brought me to the handsome, conceited little town of Los Angeles, where one finds Spanish adobes and Yankee shingles overlapping in very curious antagonism." (Plus ça change...)

The population declined (for the last time) to 50,000 by 1890, butre-bounded to 100,000 by 1900, then took off again and never looked back. Tripled by 1910, doubled again by 1920, and by the time I drove through Greater Los Angeles in March, 2003, I passed through a population approaching ten million.

Like history, geology came alive when it was felt to be true, and as I continued driving east on 1-10, I took in the macro-view. In late March, the rainy season was just tapering off, and the hills and mountains were unusually lush and verdant. To the north and east, the Hollywood Hillsamong the Santa Monica Mountains, and the lower foothills of the San Gabriels by Pasadena and Glendale, were all folds and peaks of green, villa-studded clarity. The white letters of the Hollywood sign glowed against Mount Lee, and I thought of how a little knowledge deepened my appreciation of what I was seeing.

As a recent Junior Geologist, I had been doing some reading in a subject that had once been opaque to me, and starting to build a few elementary facts into some kind of mental picture of how the actual Earth grew and changed, globally, and in the Western United States particularly. The curiosity seemed to have been inspired by traveling so much in the American Southwest, with all that naked geology, and as I so often did, I found books that educated me, by writers who entertained me. John McPhee was especially adept at combining geological information that hurt my brain with images and ideas that delighted it. Titles like Basin and Range and Assembling California had originally been written as serial articles for The New Yorker, and thus were perfectly targeted at the intelligent lay reader - or one who was willing to read the books two or three times until he could begin to apprehend, or at least approach, the concept of geological time, and to interpret the world around him as a whole new, truly fundamental, paradigm.

How could anyone ever be bored in this world, when there was so much to be interested in, to learn, to contemplate? It seemed to me that knowledge was actually fun, in the sense of being entertaining, and I had loved learning that the hills and peaks I was driving by, the ones supporting that famous Hollywood sign, were all part of the Coastal Ranges, and I had begun to understand how they were created by plate tectonics. The Pacific Plate crunched slowly against the North American Plate to push up the Sierra Nevada where they met, and, like a snow shovel, piled up the Coastal Ranges behind. Somehow, understanding how the earth beneath my feet - or wheels - was created, helped to make me feel more at home there.

Although, those were still difficult words for me to put together, "home" and "Los Angeles." When strangers asked me where I was from, I was more likely to say, "Canada," which conveyed a completely different message, and - true or not - a "friendlier" stereotype.

It is no secret that many people claim to dislike Los Angeles, and no doubt some of them have actually been there. For myself, I imagine life always depends on how big your city is - how big your world is. My Los Angeles had come to include favorite restaurants and bookstores, the County Museum of Art, the hiking trails in Temescal Canyon and Topanga State Park, and the rock formations at EI Matador beach. My Los Angeles included the Mojave Desert, the Sierra Nevada, the Pacific Ocean, the Angeles Crest Highway, Highway 33 north out of Ojai, and Mulholland Highway out past Topanga Canyon.

Within a day's motorcycle ride, my Los Angeles stretched north on the coast highway to majestic Big Sur, the Sierra Nevada national parks of Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia, across the enchanting Mojave Desert to Death Valley, or south to the Anza-Borrego desert and all the way into Baja. Indeed, I happened to know that an early start and a fast ride could put you on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon for a late lunch. If Los Angeles was not exactly a "moveable feast," it was certainly a reachable feast. And now I was stretching my Los Angeles a little farther yet- all the way to Texas.

Moving slowly eastward in the usual thick traffic on Interstate 10,through the endless suburbs of East L.A., everything blended into a flow of malls, car dealers, warehouse stores, in sta-home subdivisions, and fast food outlets (after reading Fast Food Nation, only "In 'n' Out Burger" would ever get my business again). It was difficult to imagine this land had all once been cattle ranchos, then irrigated citrus groves built around separate villages like Pasadena, Whittier, and the Mormon outpost at San Bernardino. During that late 19th-century real estate boom, the developers had soon run out of names for their invented projects, and one of them, Azusa (said to be the smoggiest city in the country these days),whose name seemed to echo native names like Cucamonga, Cahuenga, or Topanga, was actually named for "A to Z in the USA."

All those real place names ended in the "nga" suffix, meaning water, which always seemed to be the most common derivation of place names. (Every ancient place name in Canada, for example, seemed to mean either "swift-moving water," or "gathering of huts near water.") Topanga Canyon, which led from the San Fernando Valley to the Pacific, meant "place that leads to water," while Cahuenga, near a natural spring, meant "place of water." The people who gave these names were called the Yang-na, which could well have meant "people of the water."

Some of the names on the exit signs resonated for me in different ways, and at different stages of my life. Trawling back for my earliest impressions of California while growing up in Ontario, Canada, the first must have been seeing Disneyland on television, and TV shows like "77 Sunset Strip," "Highway Patrol," and "The Beverly Hillbillies." Then there would have been the "beach movies," with Frankie and Annette, at the Saturday afternoon matinees - Beach Blanket Bingo, Bikini Beach, all those, introducing me to the exotic world of surfing, sidewalk-surfing (I built my own skateboard with a piece of plywood and old roller-skate wheels), and inevitably, surf music: the Beach Boys, Jan and Dean, and the hot-rod and motorbike songs too. In later years I learned that some of those, like "Go Little Honda" and "Little GTO," were actually created and paid for by ad agencies, the latter to promote a Pontiac model (named after a legendary Ferrari) marketed by John DeLorean, who wasn't a Californian, but perhaps should have been. (His dream of building his own sports car ended in 1979 when he was arrested at a Los Angeles airport hotel trying to sell a suitcase full of cocaine to save his failing company.)

As an adolescent car nut, those songs resonated with me more than love songs did, reflecting my love for building car models and papering the walls of my room with centers pre ads from Hot Rod and Car Craftmagazines. California place names like Pomona, Riverside, and even Bakersfield were legendary to me, the homes of the Southern California drag strips. There were also drag races in a place called Ontario, California, which I had always wondered about, since I lived in the Canadian province of Ontario. I had learned, through reading some California history, that the California Ontario was actually named after the Canadian one. A self-taught engineer named George Chaffey came down from Canada in 1880 to visit, and ended up staying to become a visionary developer. He installed innovative irrigation systems, telephone lines, and a hydroelectric generator, lighting his home with the first incandescent lights west of the Rockies, and organized the Los Angeles Electric Company to make L.A. the first electrically lit city in America. So impressive was Chaffey's design for the community of Ontario that in 1903, U.S. government engineers erected a scale panorama of it at the St. Louis World's Fair.

Just after San Bernardino, I passed the exit for the road up to Lake Arrowhead and Big Bear Lake, high in the San Bernardino Mountains. In September of 2000, just before Carrie and I were married, my younger brother Danny (my best man) and I hiked a section of the Pacific Crest Trail up there, camping overnight for my "bachelor party." Each of us carried at least fifty pounds of gear in our backpacks, and as we set out on the trail we met another hiker coming from the opposite direction. Seeing our heavy packs, she asked if we were hiking the entire trail from Mexico to Canada, and we had to laugh. We were only starting a one-night hike, but included in our provisions were the ingredients for a fine dinner, including a flask of The Macallan, a bottle of chardonnay, a coffee pot, and a decadent dessert.

That Rim of the World Highway was also one of my favorite summer motorcycle routes, climbing up and winding around the mountain lakes to the west, linking with the legendary Angeles Crest Highway through miles of looping road and high pine forests, coming out above Pasadena in La Cafiada, where my friend Mark Riebling had grown up. So many connections in the grid of greater Los Angeles.

That Angeles Crest Highway was another memory, for in November of 1996, on the Test for Echo tour, Brutus and I rode our motorcycles west on that road over the San Gabriels on our way to the Los Angeles Forum for a pair of concerts. I came around a corner behind Brutus to experience the novel sight of my friend sliding down the road on his back at 50 miles-per-hour. Beside him, his fallen motorcycle was spinning slowly on its side, trailing sparks, the bright headlight rotating toward me and then away. The bike came to rest on one side of the road, Brutus on the other. Fortunately he had been wearing an armored leather suit, as we always did, and his only injury resulted from the bike's luggage case landing on his foot on the way down.

Seeing that probably saved me from a similar tumble, as I backed off the throttle and, heart pounding, held the bike straight up and down over that icy patch. I coasted to a stop beside Brutus, relieved to see him struggling to his hands and knees, shaking his helmeted head. He seemed to be all right, though well shaken up, and we picked up' his bike, which also seemed to be all right, scraped but undamaged, and carried on. Later, backstage at the Forum, Brutus was limping around and telling people how he'd "sacrificed" himself to save me, all for the sake of the show addressing a crew member with a slowly wagging finger, "To save your job, my friend!"

Brutus' foot was sore for the next couple of days, but he was able to stay and rest at the Newport Beach hotel while the band played two nights at the Los Angeles Forum. After the second show, I saw that he was still limping and feeling tender, so I suggested an alternative to us riding to Phoenix the next day: we could spend that day off resting in Newport Beach, then ride the bus overnight to Phoenix, arriving in the early morning. As part of the research I wanted to do for that book I was planning,American Echoes: Landscape with Drums, I thought it would be good to watch the whole process of assembling the show, hang around all day and take notes, and Brutus decided to video the highlights.

The crew members and truck drivers were very surprised to see Brutus and me walking in at 7:00 in the morning, and spending the whole day watching them at work. I sat out in the arena's spectator seats with my journal, writing down the progress of erecting the show, while Brutus limped around with the video camera.

Back in 2003, driving east on Interstate 10, the skyline ahead gradually came to be dominated by the high snowy dome of San Gorgonio Mountain (11,490') to the north, and to the south, its twin, snow-covered sentinel, San Jacinto Peak (10,804'). Between them, in the San Gorgonio Pass, hundreds of giant propellers on the wind farms churned in the strong Santa Ana's, accelerated through the narrowing pass by the Bernoulli effect.

I sped past a solid wall of green tamarisk trees waving in the gusts, then the view opened wide to the Coachella Valley. To the south, Palm Springs lay tucked under the San Jacintos, and to the north, the furrowed, naked brown slopes of the Little San Bernardino Mountains. Cutting west to east, Interstate 10 made an unnatural, but fairly accurate division between the lower Colorado Desert to the south and the first few Joshua trees, emblematic of the higher Mojave Desert to the north: 29 Palms, Joshua Tree National Park, and away over the creosote sea and jagged brown islands to Baker, Barstow, Death Valley, and Las Vegas.

When people asked how I liked living in Los Angeles, I usually answered that while it had its negatives - traffic, smog, crime, racial tensions, earthquakes, wildfires, mudslides, the general disregard for pedestrians, cyclists, or turn indicators (a recent favorite bumper sticker: "World Peace Begins with Turn Signals"), the shallow fixation on appearance among many Angelenos, the botox-collagen-silicone-facelift, chrome-rimmed-suv-and spa culture - it certainly had its compensations. Chief among those was Carrie, of course, who wanted to live near her friends and family, and keep up her blossoming photographic career, especially when I was away so much, but there was also the great variety of nature that abounded in Southern California - the ocean, the mountains, the desert.

I came to appreciate, and glory in, the fabulous variety of trees and plants, native and introduced, and the birds and animals: Joshua tree and creosote, redwood and sequoia, eucalyptus and live-oak, manzanita and bristlecone pine, bright orange poppies and yellow desert senna, blackbear, white-tailed deer, golden eagle, Steller's jay, and the emblem of the Southwest, coyote, the Trickster. In the holy trinity for travelers, as I had defined it in Ghost Rider, Southern California was prodigal with landscapes, highways, and wildlife.

Carrie's father, Don, a recently-retired history professor, had introduced me to many books of Californian history, from the 1840 account by William Henry Dana Jr., Two Years Before the Mast, to Carey McWilliams's pioneering examination, a century later, California: The Great Exception,from 1949. Most comprehensive of all was Kevin Starr's six-volume (so far) series documenting the "California dream" through the 20th Century. (One telling quote described Southern California by the 1950s as a place "where men who had arrived did not feel it, and those who had failed felt it too much.")

Starr's fifth volume, The Dream Endures, was the book I was carrying with me on this Big Bend journey, to be my restaurant companion. California history had come alive for me as an endlessly amazing variety of stories, of human drama, achievement, artistry, corruption, cruelty, and nobility. What Balzac called La Comédie Humaine had played out in Southern California in hyperbolic fashion, then and now, and proved the truth of Wallace Stegner's remark, "California is like the rest of America - only more so."

As the freeway descended into the valley and the traffic began to thin out at last, I relaxed a little and turned on the CD player. The first disc was the soundtrack from the movie Frida, with its evocative use of traditional Mexican instruments and melodies. The lush textures and exotic mood were working for me, casting the right atmosphere for the desert crossing, and for the journey. Not that I was headed for Mexico, but literally the next thing to it, the Big Bend of the Rio Grande River also describing the Mexican-American border.

As I started across the Mojave Desert on the long climb to Chiriaco Summit (home of the General George Patton Museum, near where he had trained his troops in the desert to prepare them for the North African campaign against Rommel in World War II), traffic began to bog down again. Generally, I hate passing on the right, but driving habits in North America are such that it is often the only way. Carefully watching my mirrors, and using my turn signals - no matter how unfamiliar that custom had become - I threaded between the gas-gulping SUVs and asthmatic Japanese compacts clumping in the left lane, and the roaring, straining semis in the right.

Next up on the CD player was Sinatra at the Sands, with Count Basie's band. As always, not only did the music I listened to accompany my journey, but it also took me on side trips, through memory and fractals of associations, threads reaching back through my whole life in ways I had forgotten, or had never suspected.

The American writer Ralph Ellison began as a musician, and wrote passionately on the subject throughout his life. In a collection of essays called Living with Music, he wrote about the power of music as a part of one's life, and even of one's culture.

Perhaps in the swift change of American society in which the meanings of one's origins are so quickly lost, one of the chief values of living with music lies in its power to give us an orientation in time. In doing so, it gives significance to all those indefinable aspects of experience which nevertheless help to make us what we are. In the swift whirl of time, music is a constant, reminding us of what we were and of that toward which we aspire. Art thou troubled? Music will not only calm, it will ennoble thee.Sinatra at the Sands was released in 1966, when I was fourteen, and it was one of the records I remembered my father playing on his console stereo. It seemed there was always music playing in our house, and it had to have an influence on me. Dad was the kind of music lover who turned on the radio when he woke up in the morning, and listened to music every waking moment, while he shaved, ate breakfast, in the car, at work, and at home, inside or out. Always there was music.

I had been playing drums for a year or so back then, and as a fan of The Who, Jimi Hendrix and the like, I didn't have much use for "old people's music," but at the same time I was so obsessed with drums and drummers that I would even watch "The Lawrence Welk Show" with my grandmother, hoping for an occasional glimpse of the drummer's champagnes par Ide drums in the background.

Obviously I didn't have much choice about hearing my dad's music, and even back then I couldn't help appreciating Sinatra at the Sands, especially the fiery arrangements (by a young Quincy Jones), and the energetic, exciting drummer, Sonny Payne. (Sonny was known for his showmanship, twirling sticks, tossing them in the air and catching them between beats. There's a story about Buddy Rich, certainly the greatest jazz drummer ever, but an intense man who preferred to dazzle with his playing rather than his juggling. Buddy appreciated Sonny's drumming, but when sticks were twirling and flying in the air, Buddy commented dryly to a friend, "He'd better watch out - he might hit something.")

A few years later, in the early '70s, when I lived in a London bed-sitter with my childhood friend Brad, I rediscovered my father's music, the big band stuff like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Frank, and I bought my own LP versions of them. I remember listening to Sinatra at the Sands on headphones many times (because our speakers were so poor - because we were so poor), and after that kind of intimate listening, even more than thirty years later I still knew every word and every note of that album. As I drove eastward across the high desert and into late afternoon, I was humming and nodding and drumming on the steering wheel as Frank and the band worked through all those great standards: "Come Fly with Me," "I've Got You Under My Skin," "Fly Me to the Moon," "Angel Eyes."

A couple of times Frank paused to deliver a "monologue," and in one of them he mentioned having recently turned 50. I had passed that milestone myself the previous September (behind my drums, fittingly, playing a show in Calgary on the Vapor Trails tour), and my reactions had ranged from a sense of the "impossible" (the notion that I had survived half a century, and also thinking back to being 20, say, and what I thought then it would be like to be 50 - ancient and decrepit), to a sense of the number being "meaningless." In an interview with Modern Drummer magazine before the tour, I was asked about that upcoming birthday, and said, "I've read that everyone has an inner age that they think they are, regardless of their actual age. I really think of myself as being about thirty. In modern life it's a matter of keeping your prime going as long as you can."

Recently a photographer friend introduced me to his young assistant, saying to him, "Tell him when you were born, Ben!" Ben told me he was born in 1976, and my immediate reaction in thinking about that date, and starting life then, was not envy, but a kind of sympathy. I shook my head and said, "You've missed so much."

For me, to have grown up through the last half of the 20th century, to have been a boy in the '50s and '60s, a young musician in the '60s and '70s, and into the '80s, '90s, and now the 21st century, seemed more valuable than being merely young. Perhaps this reaction only marked a kind of turning point of true aging, when the past seemed more important than the future - because at a certain age you suddenly have more past than future - or maybe it was the vantage point of a half-century that allowed me to feel what Wallace Stegner called "the very richness of that past."

And listening to Sinatra at the Sands, it occurred to me how Frank's singing had spanned my whole life, from childhood on, in a way that no other artist had, and how his music continued to reach me on such a deep level.

Many theories had been spun to explain the appeal of Frank's singing through decades and generations (in my own family, from my father to me, then late one night a teenaged Selena and I were driving back to Toronto from visiting friends in western New York, and I was playing Sinatra and Company, and suddenly, half asleep, Selena got it - and soon actually bought that CD for herself).

In Why Sinatra Matters, Pete Hamill wrote, "As an artist, Sinatra had only one basic subject: loneliness. His ballads are all strategies for dealing with loneliness; his up-tempo performances are expressions of release from that loneliness."

Everybody can relate to loneliness. In a Canadian context, when the members of Rush were being presented with our Order of Canada medals (a kind of "good citizenship" award), the governor-general of Canada, Romeo LeBlanc, made an eloquent bilingual speech about the shared experience of being Canadian, "We all know what it's like to be alone in the snow." (When I complimented him on that line later, he shrugged and said, "I have a good speechwriter!")

I once read a comment that Frank's singing was felt so powerfully because he seemed to be singing "to you alone," while others opine that, like Billie Holliday, he was able to convey all the passion and heartbreak of his own life when he sang. It seemed to me that the key to Sinatra's magic was that when Frank sang, he meant it. As he said himself, "Whatever else has been said about me is unimportant. When I sing, I believe I'm honest."

Perhaps the key to any great performance is just that quality: sincerity.

Of course, many singers become phenomenally successful without that magic ingredient. A golden voice and good looks will often appeal, even when it's obvious to a caring listener that when that singer delivers a song, he or she (read "diva") doesn't mean a word of it. You'd think that difference would be apparent to the listener, but I guess that is the clearest difference between art and entertainment. If people only want to be diverted and distracted, rather than moved or inspired, then fakery will do just as well as the real thing. To the indiscriminate, or uncaring, listener, it just doesn't matter. Sometimes I have to face the reality that music can be part of people's lives, like wallpaper, without being the white-hot center of their lives, as it always seemed to be for me.

All my earliest memories were like pearls grown around a grain of music or traveling. When I was three years old, we lived in a duplex on Violet Street in St. Catharines, and I remember being pulled around the block on a sled in winter. I also remember Dad proudly setting up his new General Electric hi-fi record player in the living room, so I must have picked up on his excitement about it.

A big old house, it had sunken basement windows framed in concrete below ground level, and while riding my tricycle along the driveway, I somehow fell into one of those window cavities and broke through the glass. I remember hanging upside down and looking at my mom, as she looked up in shock from the wringer-type washing machine. My first travel adventure.

Mom worked in a restaurant called the Flamingo while I was still a toddler, and I remember its shiny, lighted jukebox, and in a corner, a floodlit diorama of a pink flamingo, a plastic palm tree, and a reflective chrome sphere on a pedestal. (Perhaps my first travel fantasy.) I also remember the beginning of another lifelong addiction: my first chocolate bar. When the owners went away on vacation and we stayed there to look after the place, after dinner I was given my choice of chocolate bars from the candy counter. What joy to be able to choose, but what sweet torment having to choose. I wanted them all. (I still do.)

A friend of Mom and Dad's worked for a company which serviced the jukeboxes, and he gave them a rack of old 45s which hung around our house for years. Among them was "Wheels" by Billy Vaughn and his orchestra (another traveling song), on the flip side of "Sail Along Silvery Moon" (and heaven knows why I remember that).

One Christmas, when I was about four, we traveled by car to Virginia, where my grandparents were living, on the first "road trip" I remember. Most of our vacations were car journeys, usually camping in a canvas tent with its evocative smells of baking in the sun or mildewing in the rain. Once we stopped for the night at a motel, and I can still remember the excitement of sleeping in a rollaway cot in an unfamiliar, temporary home. My first motel stay - and far from the last. Fortunately, my reaction was excitement rather than dread, for I would be spending a good portion of my life in temporary homes, like hotels, motels, and furnished apartments. Whenever I checked into a hotel room, I felt a kind of eager anticipation. Good or bad, expensive or cheap, I locked myself into a private, anonymous space, and it felt something like home, and something like freedom.

I first achieved musical freedom when I was about ten, and my mother gave me a small plastic transistor radio. She showed me where the "Hit Parade" station was on the dial, and I remember sitting on the front step of our split-level holding that radio in my hands like a holy relic, transfixed by the notion of my own private music. (Funny that I didn't know records were played on the radio, just like on the jukebox at the Flamingo, and I thought each song was being broadcast live from the studio, with the performers moving from station to station.)

For me, that was really the beginning of loving music. I listened to that little radio constantly, searching out all the Top-Forty AM stations, WKBW in Buffalo, New York, CHUM in Toronto, and CHOW in Welland, Ontario. I would even fall asleep with that little transistor playing faintly in my ear.

Also, now that I had my own music, I had an alternative to my father's music, and the division began. It would be another ten years until I learned to appreciate Dad's music on my own, but of course once I did, it would stay with me for the rest of my life.

Sinatra at the Sands also featured a couple of slow-tempoed Basie instrumentals, "All of Me" and "Makin' Whoopee!", which showcased the tight discipline of that great band. No session musicians or generic horn section could have duplicated that dynamic swell and punch and kick, the synchronized breathing you hear when Basie's or Ellington's band played, the sound of musicians who played together night after night and really lived that music, didn't just read it.

From all those years ago, right back to childhood, the repeated snatches of Basie's theme song, "One O'Clock Jump," had so ingrained themselves in my memory that when I was choosing material to play in a Buddy Rich tribute concert and, later, recording, one of my choices had to be Buddy's band's arrangement of "One O'Clock Jump," just so I would have the chance to play that great "shout chorus," the one that appeared repeatedly on the Sinatra record.

A little more traveling music.

Before Buddy's passing in 1987, one of his final requests to his daughter, Cathy, had been for her to try to keep his band working somehow, to keep the music alive, and to "give something back" to American music. Cathy established a memorial scholarship in Buddy's name, and began presenting concerts with well-known drummers "sitting in" with Buddy's band, to raise money for the musical education of deserving young drum students. In late 1990 Cathy approached me about taking part in one of those shows, and my reply to her described my thoughts and feelings about that challenge.

I am honored that you have asked me to be a part of the Buddy Rich Memorial Scholarship Concert. In the past I have always shied away from participating in events of this nature, partly out of shyness, partly out of overwork, and partly out of a sense of inadequacy. As a rule, I do my work with Rush, and hide behind a low profile otherwise.Along with Basie's "One O'Clock Jump," I ended up choosing to perform Buddy's band's arrangement of Duke Ellington's "Cottontail," as a tribute to that giant of American music, and another tune with some nice drum breaks, called "Mexicali Nose." Through the early months of 1991, I practiced those three songs over and over (playing along with Buddy's recorded versions), and in April I drove from Toronto to New York City, and appeared with the Buddy Rich Big Band at a small theater (the Ritz, formerly Studio 54) as part of a concert featuring five other guest drummers.

But even my own rules are made to be broken, and this seems like a worthwhile occasion to come out of my self-imposed shell. Not only is it an opportunity to "give something back," but also an opportunity to fulfill a long-time ambition of my own - to play behind a big band.

Unfortunately, it turned out to be a difficult and disappointing experience for me. With minimal rehearsal time, there had been no opportunity to discover that the rest of the band was playing a different arrangement of "Mexicali Nose" than the one I had learned, and during the performance I was unable to hear the brass section at all. I struggled through it, and managed to hold it together, but after, I felt very let down by the experience I had so anticipated, and down on myself about it.

The following day I drove home to Toronto, about a 600-mile journey, and it turned out to be another occasion during which a long drive was a good opportunity to think. I left New York at dawn, feeling sad and disheartened, but as I drove, I found myself thinking about some lines from a song called "Bravado," which I had recently written for Rush's Roll the Bones album, recorded earlier in 1991. The song began, "If we burn our wings, flying too close to the sun," and resolved with the repeating line "We will pay the price, but we will not count the cost," which I borrowed from novelist John Barth, with his permission and approval. At least, I sent him a copy of the song, and he wrote back "it seems to work very well," which I chose to take as permission. And approval.

So, if I had "burned my wings" a little, taking on a challenge with all the circumstances against me, I was paying the price, but not even thinking about the cost. I just wanted to make myself feel better, and the only way to do that was to do it again, and get it right. (It also occurred to me that this was the first time I had ever been inspired by my own words!)

By the time I got back to Toronto, ten hours later, I had figured it all out. Someone was going to have to produce a Buddy Rich tribute album, so that I could play on it, and have a chance to play big-band music under more controlled conditions. Inevitably, of course, that "someone" was going to have to be me, though it took almost two more years to make that happen, between Rush recording projects and concert tours, and my own busy life of writing projects and bicycle tours to Africa.

In December, 1993, I finally wrote to Cathy and formally proposed the idea:

Recently I've been thinking about a little dream project, and I wanted to run it past you and see what you think. It seems to me it's high time for a Buddy Rich tribute album, with a number of top contemporary drummers playing the band charts - like the Scholarship videos, but with studio-quality recording. I would like to play on a track or two myself, of course, but more than that - I would like to produce the project.Cathy was equally excited about the idea, and together with her husband, Steve, and Rush's tour manager, Liam (sharing the executive producer credit with Cathy), we started working on organizing the project, co-ordinating a list of drummers and all the logistics of travel, equipment, accommodations, and studio time.

Would you be agreeable to an idea like that? Without your blessing (and help), I will certainly not go ahead with it, but if, like me, you think it would be a positive thing, I would like to proceed with some plans. We could work together in choosing which drummers to involve, which tunes to feature, the cover artwork and so on. With a little good old-fashioned hard work, I think we could turn out a very nice package.

During two weeks in May, 1994, we did the actual recording at a studio in New York City. Working with a fourteen-piece band almost entirely composed of Buddy alumni, we averaged two "guest" drummers a day, each of them recording two or three songs, mostly from Buddy's "songbook." It was a monumental undertaking, but eventually resulted in a two-volume CD called Burning for Buddy, which sold modestly (though I still enjoy listening to it - reward enough!), and even a set of videos documenting the "making of" process.

Every day I walked the ten blocks from the hotel to the studio, through midtown Manhattan and Broadway, taking different routes and enjoying the unmatched vitality of those streets. My feet raced over the pavement, so excited about what the day would bring, which drummers we would be recording with, and what new music we would be capturing. And apart from the day-to-day excitement of those sessions, and the pleasure of becoming friends with many of the drummers along the way, there was another unexpected benefit.

A few years before that project, I had worked with drummer Steve Smith on a recording with virtuoso bassist Jeff Berlin. Steve had always been a great drummer, but on the Buddy sessions I suddenly noticed a huge growth in his playing - in his technique, and, especially, his musicality. When I asked Steve what had happened to him, he smiled and gave me a one-word answer, "Freddie," referring to his teacher, Freddie Gruber.

Freddie was in his late 60s by then, and had been one of Buddy Rich's closest friends since the late '40s, when they'd met in the vibrant New York City jazz scene of those days. They stayed friends when the path of Freddie's life took him from the streets of New York out through Chicago and Las Vegas to Los Angeles, where he found his own natural calling as a teacher.

During the Burning for Buddy sessions, I met Freddie, a nonstop storyteller with a lively mind and ageless hipness, rarely without a cigarette in his hand, lit or not. I sat at dinner with him and some of the other drummers a couple of times, and in the following weeks, I became curious about what a teacher like Freddie might do for me. By that time I had been playing drums for thirty years, and was feeling as though I was playing "myself" about as well as I could - maybe it was time to, as Freddie would put it, "take this thing a little further."

The timing was certainly right, as Rush was on hiatus that year while Geddy and his wife Nancy awaited the birth of their daughter, Kyla, so in October of 1994, I arranged to spend a week working with Freddie in New York City. The first day, he watched me play for about one minute, then started talking - telling stories about Buddy and other drummers, anecdotes from his "misspent youth," encounters with Allen Ginsberg, Marlon Brando, Miles Davis, Malcolm X, Stanley Kubrick, abstract-expressionist painter Larry Rivers, and assorted hookers, junkies, and geniuses. Amid all that - look out, here comes the lesson! - he moved around the little rehearsal room, acting out the motions of soft-shoe dancers, pianists, violinists, and so on, showing me how those activities, like drumming, took place largely in the air, and ought to be more like a dance.

Also, he said, holding up a magisterial finger, "there are no straight lines in nature." Thus our movements should be circular, orbital, smooth and flowing. And, on the drums, we should pay more attention to what happens in the air, between the beats. Another of his finger-raised directives, delivered emphatically, with tall eyes, was, "Get out of the way. Let it happen! Or worse, don't prevent it from happening."

Freddie could best be compared to a tennis player's coach, always watching and correcting movement and physical technique. Freddie didn't try to teach you how to play the game - you were supposed to know that already - but he watched your "serve," or your cross-court backhand, and tried to get you moving better. So Freddie was not the kind of teacher you learned from and moved on; you could always use that kind of guidance, and Freddie had built a tight circle of faithful students for life, studio legends like Jim Keltner, recently drumming on the Simon and Garfunkel tour, and British journeyman Ian Wallace, and jazzy, rocky, so-called "fusion" (Freddie calls it "con-fusion") masters, like Steve Smith and Dave Weckl.

It was a dizzying week, full of more stories than lessons, it seemed to me, but at the end of it Freddie left me with a written list of exercises for my hands and feet, all designed to affect the motion of my entire body, eventually - though that "eventually" would require a lot of time and effort on my part. It was already clear to me that if I was going to surrender to Freddie's "vision," I would basically have to start all over again on the drums - changing the way I sat, held the drumsticks, set up the drums, and moved my hands and feet. Perhaps most daunting of all, I would have to find time to practice those exercises every day, in a busy life of work, home, and family. Practicing every day was easy and natural enough when I was thirteen and fourteen, but 30 years later, life had grown considerably more complicated.

However, I did find myself inspired and dedicated to the task, and every day I made time to go down to the basement of our Toronto house and practice on my little yellow set of Gretsch drums (seen in a drum shop window in the mid-'80s, I thought how I would have dreamed of those drums when I was sixteen - so I bought them, for the part of me that was still sixteen). As an old dog learning new tricks, I was even sitting in front of the television at night with sticks and practice pad, working on those exercises.

Over the passing weeks, I began to feel the benefits in the fluidity of my playing, and after six months, Freddie came to visit me in Toronto for another week, to "take this thing a little further," "start to put the pieces together."

"Get out of the way, let it happen."

He left me with more exercises to work on, and the practicing continued. Then again, six months later, in September of 1995, Freddie came to Quebec for another week (as a New Yorker living in Los Angeles, he loved it up there, smelling the air, floating around the lake together in my boat). More exercises, more practicing, until finally, I felt ready to actually apply those hard-won new techniques.

In early 1996, I started working with Geddy and Alex on what would be our Test for Echo album, and I could feel I had brought my playing to a whole new level, both technically and musically. Later that year, I expounded on these new directions, and on Freddie, in an instructional video, A Work in Progress.

Throughout this time, Freddie and I became close friends, and during the Test for Echo tour, he also met and became close to my best friend, Brutus. During my tragedies and subsequent "exile" in England, Brutus kept Freddie updated on my "condition," and· when I was wandering around on my motorcycle in the fall of 1998 and learned that Brutus had been arrested with a truckload of marijuana at the U.S. border in Buffalo, and was likely going "away" for awhile, Freddie understood better than anyone the weight of this latest loss. He said to me, "I thought you'd hit the very bottom of life already, but now you've hit lower than bottom - you've hit lead!"

Just after a five-day stay at Freddie's house in the San Fernando Valley in November of 1999, I started a letter to Brutus from my accommodations in Show Low, Arizona, to his at the Federal Detention Facility in Batavia, New York. Coincidentally, I was on my way to Big Bend that time too, though I never made it (for reasons that will be revealed), and that letter also happened to contain some "traveling music," and tell of a journey eastward on Interstate 10, near where I was driving in March of 2003.

As I closed in on Blythe, California, the Colorado River and the Arizona line, who should be up next on the CD changer but Buddy Rich, in a sweet coincidence, and a sublime recording with Buddy's band and Mel Tormé, called Together Again - For the First Time.

So many connections on this traveling roadshow.

From a letter to Brutus, dated November 15, 1999, telling about my stay with Freddie.

Anyway, every day there was sunny and warm, and every night was cool and clear. I would layout in his backyard at night in the one operable chaise longue, and look up at Orion, the Pleiades, the star I think is Arcturus, and all the rest.That letter continued from Tucson the following day, November 16, 1999, and it also happened that in March 2003, I would be passing through Tucson the following day, three and a half eventful years later.

Airplanes high and low, shooting stars, a fingernail moon. Eight cypress trees in the neighbor's yard, a shaggy, silhouetted palm. Radio station KGIL, "America's Best Music," plays from the Silvertone radio in the laundry closet, in the half-covered patio, and in the dark living room, coming on every afternoon at 4:00, on a timer. Their playlist could be sublime - an instrumental version of the Ellington-Strayhorn classic, "Don't Get Around Much Anymore," then "He'll Have to Go" ("Put your sweet lips, a little closer, to the phone"), "Cherish," "I Love How You Love Me," and "Maria," from West Side Story.

Or another set which included "Take Five," "Unchained Melody," "Only You," by the Platters, Dusty Springfield's "Wishing and Hoping," and Ed Ames doing a heartbreaker (for me) "Sunrise, Sunset" - "Is that the little girl I used to carry" .. . Ach. Other greats I hadn't known about: Errol Garner, Dick Haimes - or hadn't fully appreciated - Bobby Darin, Eydie Gorme (really!). Altogether, as before, Freddie's "pad" is a timeless oasis of sanctuary, a hideaway, but with the two of us in various "states," and me already a little "beat up" after ten days in L.A.