|

(Preview) by Neil Peart © 1996 |

Click Any of the Following Images to Enlarge

Africa is the continent where both life and art began.

By November 1988, when Neil Peart arrived in Cameroon, he'd been expanding his own life and art through almost twenty years of travel and adventure. Concert tours of North America and Europe with his Rush bandmates, and the shared creative odyssey of lyric-writing and drumming, had only fed his insatiable curiosity and creative ambition. Through solo travels in Europe and North America, then to China and East Africa, he continued challenging himself to do more, learn more, achieve more.

Adventure travels moved from inspiration to perspiration and back again, as that irresistible quest for new horizons and new adventures inspired the wish to shape those horizons and share those adventures in words. Like a story, each journey took on a shape and structure from beginning to end, through daily challenges of problem-solving and adaptation, and resonated in his life forever after. Experiences, hardships, and exultant survival enriched his worldview twice over -- once in the living, and again in the challenge of capturing them in words.

Adventure travels moved from inspiration to perspiration and back again, as that irresistible quest for new horizons and new adventures inspired the wish to shape those horizons and share those adventures in words. Like a story, each journey took on a shape and structure from beginning to end, through daily challenges of problem-solving and adaptation, and resonated in his life forever after. Experiences, hardships, and exultant survival enriched his worldview twice over -- once in the living, and again in the challenge of capturing them in words.

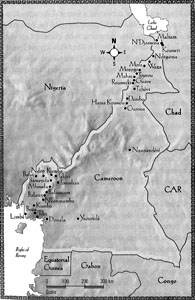

Now 36, Peart was ready to attempt two of the greatest challenges of his life. The month-long bicycle tour through Cameroon would be his first trip through West Africa. Covering more than a thousand miles of primitive roads, trails, and goat paths, it was considered "the most difficult bike tour on the market."

He had chosen to travel by bicycle. at "people speed," because his other great challenge was creative. With notebook. tape recorder, camera, and an author's transformative perspective and awareness, Peart's goal was to inspire, "inhale." his experiences of the sub-Saharan country, its cultures and art, religions, languages, multiple ethnic and colonial histories, and especially, its people - chiefs and villagers, soldiers and schoolchildren. missionaries and prostitutes - so comprehensively and imaginatively, that in "exhaling," he could write with sufficient insight, accuracy of understanding, and vividness of memory, that his story would reveal and illuminate for the Western world something of the "face" behind the mask of Africa.

Peart's creative achievement as author became his first published book, and in the eight years since its original publication in 1996, The Masked Rider has become appreciated by readers worldwide as a rare, special, and unforgettable travel memoir and portrait of West Africa, as seen through the mask of the visiting "white man," and through the equally complex masks of the Africans themselves.

To my mother and father

who brought me up to know better ...

Continuing thanks to Mark Riebling and Danny Peart

for criticism and advice

And to Jackie and Selena

for allowing the time

Introduction

Part One

White Man, Where You Going?

Chapter 1 - InfernoPart Two

Chapter 2 - Dance Party

Chapter 3 - Hell Hole

Chapter 4 - Hotel Happy

Chapter 5 - The Larger Bowl

Epiphanies and Apostasies

Chapter 6 - Epiphany at VespersPart Three

Chapter 7 - The Missionary Position

Chapter 8 - Encounters

Chapter 9 - The Good Heart

Chapter 10 - The Paved Road

Chapter 11 - People on the Bus

Chapter 12 - The Beaten Track

Chapter 13 - Quixote and Quasimodo

White Man, What You Doing?

Chapter 14 - Watermelon and Satellites

Chapter 15 - Toil and Trouble

Chapter 16 - The Lizards are Fat at Waza

Chapter 17 - African Nightmares

Chapter 18 - Parisian Dreams

Introduction

It is said that one travels to East Africa for the animals, and to West Africa for the people. My first dream of Africa was a siren-call from the East African savanna ... great herds of wildlife shimmering in the heat haze of the 5erengeti, the Rift Valley lakes swarming with birds, the icy summit of Kilimanjaro. So I went there, and I loved it. The following year I went looking for an interesting way to visit West Africa, to learn more about the African people - the animals drew me to Africa, but the people brought me back.

After much searching I found a name - Bicycle Africa - and signed up for a month-long tour of "Cameroon: Country of Contrasts." At the end of it I swore I'd never do anything like that again - but the following year I forgot my vow, and returned to bicycle through Togo, Ghana, and the Ivory Coast.

Cycling is a good way to travel anywhere, but especially in Africa; you are independent and mobile, and yet travel at "people speed" - fast enough to move on to another town in the cooler morning hours, but slow enough to meet the people: the old farmer at the roadside who raises his hand and says "You are welcome," the tireless woman who offers a shy smile to a passing cyclist, the children whose laughter transcends the humblest home. The unconditional welcome to tired travelers is part of the charm, but it is also what is simply African: the villages and markets, the way people live and work, their cheerful (or at least stoic) acceptance of adversity, and their rich culture: the music, the magic, the carvings - the masks of Africa.

Africa is such a network of illusions, a double-faced mask. It is as difficult to see into it as it is to see out of it. To those who've never been there it is an utter mystery, a continent veiled in myths and mistaken impressions, but it is equally obscure to those who have never been anywhere else. It used to be said that electronic media would bring the world closer together, but too often the focus on the sensational only distorts the reality - drives us farther apart. That is why in Ghana the children followed me down the street chanting "Rambo! Rambo!" and that is why Canadians look at me as if I were a lunatic when I tell them I've been cycling in Africa - they can only picture it from wildlife documentaries, TV images of starvation camps, and old Tarzan movies.

Africa fascinates me - in the true sense, I suppose, as a snake is said to transfix its prey. And the more times I return, the more countries I visit, the more the place perplexes me. Africa has so much magic, but so much madness. Yet I keep returning, and surely will again. This attraction is compelling and seems to grow stronger, but, like any lasting relationship, it is no longer blind.

And maybe that's always true. After the first infatuation we're always most critical of what we feel the strongest about. It's too often the case in relationships, and certainly regarding one's own family or country. You can criticize your own, but don't let anyone else try it. That's when love shows its teeth.

If my attraction to Africa is no longer blind, it is still blurry. From within and without, Africa is as much the "Dark Continent" as it was two hundred years ago - hard to see into, hard to see out of. The mask obscures a face which is so complex and contradictory; it takes a lot of traveling even to get a sense of it. And traveling in Africa is, by necessity, adventure travel.

Some people travel for pleasure, and sometimes find adventure; others travel for adventure, and sometimes find pleasure. The best part of adventure travel, it seems to me, is thinking about it. A journey to a remote place is exciting to look forward to, certainly rewarding to look back upon, but not always pleasurable to live minute by minute. Reality has a tendency to be so uncomfortably real.

But that's the price of admission - you have to do it. One reason for making such a journey is to experience the mystery of unknown places, but another, perhaps more important, reason is to take yourself out of your "context" - home, job, and friends. Travel is its own reward, but traveling among strangers can show you as much about yourself as it does about them. To your companions and the people you encounter you are the stranger; to them you are a brand-new person.

That's something to think about, and if you try you might glimpse yourself that way, without a past, without a context, without a mask. That can be a little scary, no question, but you may get a look behind someone else's mask as well, and that can be even scarier.

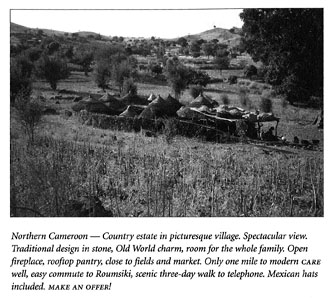

Click Any of the Following Images to Enlarge

Chapter 1 - Inferno

The first traveler's tale of Cameroon reaches us from the fifth century B.C., when the Phoenician explorer Hanno led an expedition around the west coast of Africa. His fleet of sixty ships reached present-day Senegal, and Hanno attempted to land there, but was soon driven back by the local warriors. He sailed on past forested mountains and wide rivers, afraid to go ashore because of the hippopotamuses and crocodiles (it would appear Hanno wasn't the most stalwart of explorers). He came upon an island which looked safe at first, but when he tried to land he was frightened off again, this time by "fires and strange music." And once more he ran away, stating,

Sailing quickly away thence, we passed by a country burning with fires and perfumes and streams of fire supplied then fell into the sea. The country was impassable on account of the great heat. We sailed quickly thence being much terrified and passing on for four days we discovered at night a country full of fire. In the middle was a lofty fire which seemed to touch the stars.

Next morning, just before Hanno "sailed quickly away" again, this time for home, he saw a mountain of fire which he named Theon Ochema: the Chariot of the Gods. Being "much terrified," Hanno was no doubt given to exaggeration, but Mount Cameroon, the only live volcano in West Africa, is said to be that great mountain of fire which kept the tourists out of Cameroon for another two thousand years.

Then, in the sixteenth century, the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama cruised by and dropped anchor in the Wouri River. He stood at the rail and admired the small crustaceans in the water, and decided to name the river after them: Rio-des-Cameroes, "River of Prawns." Thus the Portuguese called their "discovery" Cameroes, until 1887 when the Germans claimed the land and called it Kamerun. After World War I it was taken from Germany and divided between the French, who called it Cameroun, and the English, who called it The Cameroons. What the people who lived there called it is not recorded, but no doubt it had nothing to do with small crustaceans.

By the time I got to Cameroon, in November 1988, the country was once again in the hands of the people who lived there. I saw no mountain of fire, and I saw no prawns, but my first impression of Cameroon was not unlike Hanno's: heat and darkness and fires, a strange inferno which did seem to suggest "sailing quickly away thence." The air was heavy, even at sunset, and the exertion of assembling my bicycle outside the airport left me dripping. Among a confusion of upended frames, wheels, bike-bags, and tools, a crowd of boys gathered around to watch me and a few other North Americans struggle with our handlebar stems and seat posts. I kept an uneasy watch on my possessions, and thought about cycling around Cameroon for a month in that kind of heat. A month can be a long time.

We pedaled away from the airport into the sudden equatorial night, following the broken shoulder of the highway into the city. A few dim streetlamps lit the skeletons of abandoned cars and uneven rows of gray plank and cinder-block houses. Corrugated-metal roofs gleamed among the looming, ivy-hung trees. Scattered oil-drum fires flickered on dark faces, flashing eyes, and teeth bared in demonic laughter that was drowned by the music which raged out from everywhere. Indecipherable wailing chants and pulsing rhythms chugged out of straining loudspeakers as I tried to find a path through the crowds. People turned to stare, evidently surprised to see a white man in a funny hat riding a bicycle.

We pedaled away from the airport into the sudden equatorial night, following the broken shoulder of the highway into the city. A few dim streetlamps lit the skeletons of abandoned cars and uneven rows of gray plank and cinder-block houses. Corrugated-metal roofs gleamed among the looming, ivy-hung trees. Scattered oil-drum fires flickered on dark faces, flashing eyes, and teeth bared in demonic laughter that was drowned by the music which raged out from everywhere. Indecipherable wailing chants and pulsing rhythms chugged out of straining loudspeakers as I tried to find a path through the crowds. People turned to stare, evidently surprised to see a white man in a funny hat riding a bicycle.

One of the oil-drum fires lighted a member of our group at the roadside, where he had stopped to ask directions. The light flickered on his curly dark hair and beard, framing close-set eyes and vaguely Middle-Eastern features. That was David, our guide from Bicycle Africa - also, we learned, its founder, director, and secretary. "My office looks suspiciously like my bedroom," he confessed with a laugh.

Only later did David tell us that "Cameroon: Country of Contrasts" was "the most difficult bicycle tour on the market." He had been advertising it for two years and could only attract four customers. Us. He had led a tour of Cameroon just once before, two years earlier, with only three clients, one of whom, like Hanno, had turned around and gone home in less than a week. Had I known these things as I followed David's white helmet through the shadowy crowds, my excitement might have been tempered. But that's the good part about the future: it doesn't have to contain any flaws until it becomes the present.

I had enough to worry about in the dark here-and-now of crowded streets, sudden taxis, motorcycles, and crater-sized potholes. Everything seemed to blare like car horns: the music, the smells, the faces, the headlights, all in dizzy confusion. I tried to concentrate on my riding and keep an eye on David up ahead. I didn't want to miss a turn and get lost in the gauntlet of madness which seemed to comprise Douala, the largest city in Cameroon.

We made our way to the Hôtel Kontchupé, a chain of low buildings on a narrow street above the waterfront, where I could see the lights in the rigging of a small freighter. We parked our bicycles on a terrace fenced with black wrought iron. A mural decorated one mustard-colored wall, a montage of musical instruments, masks, and a pre-Cubist angular figure raising what looked like a martini glass.

Three of us moved along the terrace to the Café des Sports while David spoke with the manager in "survival French," the same kind I possessed. Still too early in the evening for nightlife, the bar was empty and smelled of stale beer and cigarette smoke. The young bartender was just putting on a record, and West African rhythms pumped out of the speakers. The walls were decorated with lurid black-light posters of skeletal bikers and voluptuous leather-clad females. After a long look around, the three of us took a seat at the bar.

Usually when I begin a trip like that, the hardest thing is learning everybody's name. You meet ten or twenty people at one time, and their names float right through your head, or, as often happens, your brain assigns them names which suit them, but aren't necessarily theirs. You put on an open-friendly face, try to make neutral conversation, and wait for someone else to address them by name. This time, though, it would be easy - only five people on the tour, and I knew two of their names already: David's and my Own.

I helped my two companions order drinks, as they were from California, where French is normally limited to Chardonnay and Perrier. I was getting their names now. Leonard was the tall black guy with the thick rimless glasses, and Elsa was the older woman, slender, with short pale hair and sharp features. No problem. Then a commotion outside intruded, even over the loud music, and the three of us moved to the door. A Japanese taxi was pulled up in front of the hotel, and David was helping the driver lift a boxed bicycle out of the trunk. Our fifth rider had arrived, and she stood looking on, her hands moving as if she wanted to help but didn't know what to do. I couldn't remember her name from the roster, but David came to my rescue. "This is Annie." While I shook her hand I tried to stamp it into my memory. Okay, Annie. Leonard is the tall black guy; Elsa is the older woman, and Annie is the long dark hair with the open-mouth smile.

Annie joined us in the bar, still smiling, her hands still tending to move as if she wanted to help but didn't know what to do. Someone asked about her job, described on the roster as systems analyst.

"The ultimate post-modern job description," I said with a laugh.

"Um, well ... heh-heh ... it's the best definition I could think of for a kind of ... um ... everything job," Annie said, and we nodded and smiled and made small talk with the conscious politeness of strangers who know they are going to be living together for a month. A month can be a long time.

David returned to lead us to our rooms, back into the hotel side of the building and through a maze of stairs and corridors, something M.C. Escher might have drawn. One room for the men, one for the women, and all of us sharing a dingy toilet which crouched in a closet along the zigzag hall. An arched doorway led into our room: green linoleum floor, dark ceiling of peeling wood, and walls of grimy white stucco decorated with an incongruous Afro-Arabian-gypsy-disco kind of hanging. Naked bulbs in the corners spread feeble light down over two drooping beds. The bar downstairs was warming up for the night, and the music vibrated up through the walls.

Having inspected the room, we decided to go out for something to eat. Just as we stepped off the terrace of the Hôtel Kontchupé, one of a group of men standing there called out to us. It appeared to be a warning, but the rudimentary French which David and I possessed could not decipher it. Then I realized he was pointing at my leather beltpack, and telling me to be careful against thieves.

Now I had just finished reading a section in Africa on a Shoestring on Douala:

It isn't a particularly pleasant place: mosquitoes and muggings are both problems at night, so watch out. Even during the day you may well find suspiciously-looking people following you around waiting for the right opportunity.

So although my bag was firmly attached around my waist, I closed one hand around it and put on what I hoped was a menacing face. As we turned the corner into the main street, David suggested that in a place like Douala he made it a point to walk down the middle of the street at night. It seemed like an excellent idea.

Unlike the part of town we had ridden through earlier, this was not an area of nightlife. No inferno here; in the humid half-light it wore the air of a decadent avenue after midnight. Lone cars whisked by at intervals. The sparse streetlights were further attenuated by thick trees, ferns growing between the limbs and vines along the branches. Most of the store windows were protected by iron grilles, guarding displays of cheap furniture, appliances, stereo equipment, and even a croissant shop.

A row of trestle-tables along the sidewalk offered the only life and the only visible commerce, a kind of on-the-street convenience store selling food, drinks, and cigarettes. David spoke to a thread-bare man who tended a glowing brazier, and we sat down on a rough wooden bench while he cracked eggs into a pan.

The dark boulevard was called the Boulevard du Président Ahmadou Ahidjo, and I'd learned something about that name. Ahidjo had been the president of Cameroon from independence in 1961 until 1982, when he stepped down in favor of his chosen successor, the current president Paul Biya. For some reason Ahidjo changed his mind, and in 1984 attempted a coup from outside the country. Though unsuccessful, there was bloody fighting in the streets of Yaoundé, the capital city, and the aftermath was sweeping. Ahidjo had represented the Islamic northerners, many of whom were purged from the government. Strikes were banned, the national press became a propaganda puppet, foreign journalists came under continual harassment, and the government adopted unlimited powers to suppress dissidence. Amnesty International claims that Cameroon keeps hundreds of political prisoners imprisoned without trial. The most visible effect to us would be that, because the coup had been engineered from outside Cameroon, a deep suspicion of foreigners was forged. For the next month we would travel under the shadow of that xenophobia.

The omelette man delivered his wares one at a time, lifting the fried circles of smashed eggs onto plastic plates, then passing us a boxful of cutlery. The omelette was excellent, spiced with sausage and pimento. By the glow of a kerosene lamp, small talk flickered among our group, and I smiled to be alone among strangers once again, in a place I'd barely heard of just a few months before.

We strolled a little farther along the quiet street, everything indistinct and a little spooky in the shadow of the trees, and reached a corner where a closed gas station served as a gathering place for a crowd of lounging youths. When they turned toward us and began to mutter among themselves, David suggested it might be prudent to retrace our steps to the hotel.

The walls of our room still rocked with the exuberant music from the downstairs bar, which had modulated into a series of American '50S rock. But I had no trouble falling into a deep sleep, even to the throbbing lullaby of "Rock Around the Clock."

Though the Hôtel Kontchupé was in the heart of the city, I awoke to the sound of roosters, as I would nearly every morning in Cameroon. We packed our belongings into our panniers and hung them on the bikes, then pedaled a short way down Boulevard du Président Ahmadou Ahidjo to the croissant shop. The morning was already hot, though the sky was white with overcast, as we lined our bikes together against a tree and took a table by the street.

People hurried past along the sidewalk, the men wearing Western-style trousers and light-colored shirts, though a few wore the long Islamic robes of white cotton. Some women dressed in blouses and modest skirts, but most seemed to be clad in the colorful print wraps called pagnes, which covered them from the waist to the ankles, with a matching headscarf and a plain blouse. They were handsome people, strong well-formed bodies walking proudly, and their features were often arrayed in a nearly circular symmetry of mouth and eyebrows, sometimes suggesting a moon-face. We looked raw and pink and conspicuous, except for Leonard, and men and women alike turned to look at us. But these were sophisticated urbanites. They never broke stride.

After strong coffee and rolls, we climbed back on the bicycles and rode out into the traffic. Concrete buildings of two or three stories were painted in pale colors, but stained by mold and smoke, their walls hung with crumbling balconies and weathered shutters. Slender palms curved overhead, while giant ferns and exotic shrubs crowded over the walls like clusters of green swords. I moved in behind Leonard, and as we pedaled through town I watched his gray T-shirt darken with sweat.

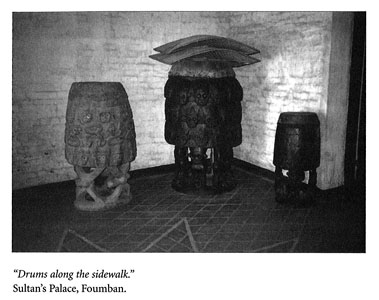

We covered the last-minute errands: changing money, buying the postcards and stamps which would not be available where we were going. During a quick tour of the artisan's market we were urged by the voices and gestures of the merchants to spend some time and money with them, but we only scanned the carvings, spears, masks, drums, and brass figurines. As David pointed out, "If you're thinking seriously about buying anything, you'd better think seriously about carrying it around for a thousand miles."

By mid-morning the heat had become an electric blanket, and even the trees appeared to droop over the roadway, wilting in the humid swelter. It was already apparent that Elsa was going to have trouble, as we waited for her at every intersection and stop. (Basic rule of bike touring: Always wait for the next rider at a turn, and the last rider should never be left alone.) But, at sixty years old, Elsa was entitled to allowances, and a slower rider is not necessarily a problem among a faster group. You see more by stopping occasionally to wait for them than you would by pedaling steadily along, and it can be more relaxing to hang back and take it easy. I made a mental resolution to try to be more relaxed in my own pace, not be so driven and urgent to reach the destination every day. I would take time to enjoy it; I would stay back with Elsa.

At last we were on our way out of town. A long, crumbling causeway traversed the Wouri River (the one Vasco da Gama had named the River of Prawns), wide and shallow near its delta, then led us into a low-lying coastal region. Heavy waving reeds and grasses on either side of the road gave way to tall palms and opaque deciduous trees. Occasional patches of pond and swamp opened among the greenery, and made a home for water birds like the hamerkop, a peculiar bird I'd come to know in East Africa.

The hamerkop is a small brown heron, named for its ice-axe-shaped head. It is known as "The Lightning Bird," or "The King of Birds" to Africans, and is enshrined in myth and legend. East Africans call it The King of Birds because of its palatial taste in residences, for each year a pair of hamerkops selects a tree overhanging the water, then spends three months (a long time in birdland) building a roughly spherical mass of sticks up to six feet in diameter, with a small side entrance. Once the family has been raised and the home abandoned, it will be replaced by a new palace every year, and the huge nest will provide tenement living for other creatures: snakes, rodents, insects, owls, and penthouse-dwelling hawks.

Just after I passed a third hamerkop stalking a choked waterway, I had to pull over and stop on the shoulder while a herd of longhorn cattle plodded across, tended by a stick-wielding farmer. Straddling the bike, I reached down for my plastic bottle and squeezed the warm water into my mouth. The farmer waved and smiled as he passed me, but his features were strangely twisted. His mouth smiled, but his brows were knit in dubious wonder.

High noon in Africa is an expressive enough description of the heat. An hour's cycling had taken me about twelve miles, an average cruising speed, but I felt as if I'd been racing. My whole body streamed with sweat, and I was already working on my second water bottle. Spying the burned-out hulk of a car at the roadside, I wheeled in beside it and rested one foot on its rust-blotched fender. I was surprised to see how much of a car can burn, and how much can melt; the rearview mirrors had drooped down the side like a Dali painting.

Leonard pulled up behind me, taking the red bandana from around his neck and wiping his face and trim beard, cleaning the rimless glasses, then swallowing a draft of water. Another bandana, a blue one, covered his head (he was the only one of us who didn't wear a helmet), and he was sweating furiously. I was astonished to see him pull off his T-shirt and actually wring it out between his hands, a stream of water dripping to the ground. "Elsa's just a bit behind me," he said. "She's having a rough time, I've had to wait for her a lot."

I agreed to stay back with her for awhile, and he was gone down the road. I noticed for the first time what a relaxed and confident riding style he had, strong runner's legs spinning slowly, and his long body centered easily in the saddle. The previous night Leonard had told me he did a lot of running, and I'd also learned that he was a Vietnam veteran - days he referred to as "when I worked for the government." Now he worked for IBM as an electrical engineer, and his favorite thing, he told me, was flying gliders, "when I can afford it."

I baked by the burned-out car for twenty minutes until Elsa coasted to a stop behind me, gasping and slumping over the handlebars. "Doesn't David ever stop?" she said, with petulance on her sharp features and a hint of despair in her voice. "This heat ... "

"We're going to stop soon. He knows a place at the crossroads up ahead where we can buy some drinks."

"How far up ahead? I feel all light-headed."

"Not far," I lied, thinking that if twelve miles of flat road was giving her such a rough time, she could be in for worse. At sixty years old, it was her first bicycle tour, though the previous night she'd made a point of telling us she'd been training for three months, swimming every day, and had once done a seventy-five-mile bike ride. (Uh ... once?) But she seemed to be fit enough; more worrisome was her "externalizing." Blaming David, the heat, the distance. Her face was a mask of bitterness, and I tried to cheer her up.

"Yeah, the first day, with the jet lag and everything, sometimes it hits you that way. It happened to me on the first day of a bike tour once, in Spain, when I suddenly conked out in the afternoon. Same thing, I went all light-headed. It was a horrible feeling."

Finally she pushed off down the road, and I fell in behind her, pedaling slowly to match her unsteady pace and pulling up at her frequent stops. Elsa hadn't learned how to drink from her water bottle while riding, and so had to stop each time she wanted a drink. Maybe she just wanted to stop. I could imagine the dark cloud in her brain and didn't say anything more.

When the crossroads finally came into view, I saw three bicycles leaning against the porch of a small brown building, and three riders sitting on benches in the shade with bottles of soda. Signs on the wall behind them advertised Guinness beer - "It's Good for You" - Canada Dry - "C'est Cool" - and other drinks and cigarettes in a mixture of French and English.

Elsa and I leaned our bikes beside the others, and she stumbled across the porch and lay back on one of the benches, both arms raised over her face. I bought another bottle of spring water for myself, and then brought out a Fanta orange for Elsa. She half-rose enough to drink it down, then collapsed back again. But when I stepped away to take a photo of her "in repose" she suddenly leaped up, dashed to her bicycle, pulled out her camera, and handed it to me, then hopped back to the bench and resumed her state of supine exhaustion. I took her picture.

We turned west at the crossroads, onto a quiet road bordered by shoulder-high grass and dense rainforest. The roar of passing diesels was replaced by the ceaseless whirr of insects - big-sounding insects. David and I rode together at the back of the pack, pedaling easily along the paved road. The keychain thermometer on my handlebar bag showed ninety degrees. A flattened reptile lay pressed into the pavement, a dry and stiff length of skin.

I began to notice brown lumps on the road, scattered like crushed seedpods. Looking closer as my wheels passed over one, I saw that it resembled a giant worm, with a segmented carapace and macerated insides. But I mean a giant worm, about six inches long and two inches thick, and I remarked to David that these were even more revolting than the slugs of his native Pacific Northwest.

"Nah," he grinned. "Just everyday old millipedes."

I asked David when he'd started bicycle touring, and he told me he'd first crossed the United States nearly twenty years before. I was impressed by his story of back-to-back touring days of two hundred miles, a punishing distance even to do once, on an unladen bicycle, let alone for days on end with a loaded touring bike. After college David had signed up as a Peace Corps volunteer in Liberia, and had brought his bike with him to that small West African country. When his two-year teaching stint was up, he'd set out to explore more of the continent, eventually traveling through more than half of the countries in Africa.

From those experiences had come the International Bicycling Fund, which he established to lobby for cyclists, and especially to promote cycling as transportation for the Third World. Then came Bicycle Africa, to introduce Westerners to East and West Africa by this friendly and efficient mode of transport, and also to introduce Africans to the sight of white people in funny hats riding bicycles. He was a good guide too, even knew the names of birds.

A black-and-white crow flapped across the road ahead of us, and David raised a hand from the bars to indicate it. "Pied crow, probably the most common bird in West Africa." I saw that its name derived from the white "T-shirt" over its chest and wings. Higher up a dark bird of prey circled above the forest, wings held out motionless and its wedge-shaped tail acting as rudder, angling sharply to one side and the other.

"Some kind of kite," offered David, not very scientifically.

Although most of Cameroon is poor agricultural land, much of it dry grasslands, and eighty percent of the people survive on subsistence farming, in this coastal area near Mount Cameroon the soil was rich, and the rainfall plentiful. Rainforests and plantations of rubber trees, banana, and oil palms crowded up to the road, and above all rose the silk-cotton trees, towering two hundred feet and more. They stood in solitary grandeur, smooth elephant-gray trunks rising way up to graceful fans of leaves.

Elsa had fallen behind again, and David stopped to wait for her while I pedaled on ahead to catch Leonard and Annie. Together we stopped in the shade of a mango tree. A small house stood nearby, its walls of gray planks decorated with a few beer and soft-drink signs. A design of bottle caps had been pressed into the clean-swept earth in front. There was no sign of anyone. Goats, chickens, and pigs wandered freely around the house, scratching and rooting for food as we rested in the shade and drank from our water bottles. I started a chorus of "Underneath the Mango Tree," and Leonard laughed me into silence just as David and Elsa came riding up. Elsa was grateful for another break.

"I like it here," I said to no one in particular.

"Yeah, it's a nice spot," said David. "When we get to the north, where it's really hot" (Elsa's eyes flashed at this), "it's nice to find a place like this in the late morning, and take a siesta for a couple of hours. Otherwise the midday heat just sucks the strength right out of you."

Another cyclist rolled by, an African man in his forties wearing a straw hat and riding a battered old Chinese bike with two large baskets sagging to either side. I remarked that this was the root of the name "panniers" - French for baskets - which we gave to our saddlebags, and this cyclist's true panniers were weighed down with a five-gallon plastic container on each side, both of which seemed to be full. That would be twice the weight that any of us was carrying, with the exception of David, whose mountain bike was loaded with panniers over the front and rear wheels, carrying a selection of arcane tools, bike parts, books, maps, water filters, waterbags, and items he had brought as presents, like calendars, T-shirts, and International Bicycle Fund newsletters, in addition to his clothes and bedroll.

When I finally rose from the comfortable mango tree and pushed my bike back to the road, I noticed a home-made sign, posted where a trail led away between the ragged palms:

______________________________

DANGER

KOKE BRIDGE IS VERY-UN SAFE

YOU ARE CROSSING IT

AT A VERY BIG RISK

______________________________

But we weren't going that way.

Another two hours of paved road brought us to the Airport Hotel near Tiko. No airport appeared on the map, and none was visible from the road, but as we stood before the wrought-iron gates of the hotel a sudden roar burst into the air, and a big airplane banked steeply just above the trees. Leonard identified it as an American C4-B, a four-engine military cargo plane ("working for the government" had educated him well in the machines of war). No one could imagine what it might be doing in the tiny village of Tiko, as we shaded our eyes and watched it drone into the distance, disappearing into the clouds toward the long shadow of Mount Cameroon.

That mountain was a looming presence in our future, as we knew that in two days we would be cycling up to the highest town on its shoulder. Mount Cameroon is a broad-shouldered old volcano (Theon Ochema, the Chariot of the Gods), and it is the tallest mountain in West Africa. Its seaward slopes attract the abundant rain; the coastal town of Debundscha is said to be the second-wettest place in the world, drenched by over a thousand centimeters of rain annually. In contrast, the dry north of Cameroon, where we would end our travels, receives only fifty-four centimeters a year.

The Airport Hotel was surrounded by high walls of concrete and spiked wrought iron, its name printed on a billboard showing Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and a large bottle of orange pop, with the slogan "My Friend Fanta." Behind the sliding iron gate was a wide terrace roofed in sheets of corrugated metal, and behind it the two-story concrete building. For all its fortifications, the place seemed deserted, but David eventually found a sleepy young guy who sold us cold drinks from the bar, and told us it would take a while for the rooms to be ready.

David and Elsa took the benches and quickly fell asleep, while I sat with Leonard and Annie, talking quietly. A curious poster was pasted to the wall, just under a "Guinness Is Good for You" sign:

______________________________________

DON'T HELP IN THE TRANSMISSION OF AIDS

with a cartoon of a young couple cuddling on a bench.

"You and me," says the boy, in blue trousers and shirt, and penny loafers.

"Until death," replies the corn-rolled and modestly dressed girl.

STICK TO ONE PARTNER OR SAME

PARTNERS IN CASE OF POLYGAMY

______________________________________

It was nearly dark before we finally hauled our bikes up the stairs, once again divided by gender into two rooms. Ours was large, though furnished with a single small bed, and the plastered walls were grubby and scarred by smashed insects and the afterthought of electrical wiring. An antiquated air conditioner chugged ineffectually beneath the glass-louvered window, and the linoleum was crusted with grime like the floor of a gas station.

We did have the unexpected luxury of an "en suite" bathroom, a cube of raw concrete with stained fixtures and a shower-head which spilled unheated water onto the floor. But even a cold shower was welcome, and with clean clothes on I felt revived and ready for the walk into Tiko in search of food.

I had noticed all day that no one wore shorts, except very small children, no matter how warm it was. David told us it was a matter of modesty, but it was acceptable for us to wear shorts while on the bikes, being "sportifs." He had already advised the women to wear long pants or a skirt whenever they were off their bikes, and suggested that Leonard and I would feel more comfortable if we dressed according to local customs. I don't know if "comfortable" is the word, as it was often damned unpleasant pulling on long trousers in ninety-degree heat, but we agreed that we didn't want to offend anyone.

You had to blame the missionaries. The West Africans had once gone about comfortably and suitably naked, or nearly so, and it had been the prudish missionaries, so often the emissaries of Western civilization, who had convinced the Africans that God wanted them to wear trousers, shirts, and dresses. Though Africa has finally thrown off the white man's rule, some things, though alien to the African world-view, had been planted too deep - commerce, politics, real estate, colonial borders, and prudery. When Cameroon gained its independence in 1961, the new government even issued a directive that women were to dress "decently and modestly," meaning no more naked breasts.

The road into town was unlighted, and Leonard and I tried to pick out a path with our flashlights. An occasional passing car blinded us, and with the night sky shrouded in black clouds it was as if we moved through a tunnel. Small groups of people, all but invisible, appeared suddenly before us, then passed on, talk and laughter carrying on the air.

The road ended suddenly, and we stumbled through the ruts of the village streets. David led us to the market, where a few oil-drum fires flickered on people carrying boxes and baskets from the kiosks to a cluster of cars, gleams of glass and metal in the darkness. The market appeared to be closing, though music still blared from every direction, each speaker trying to outdo the other in volume, if not in fidelity. Again the Inferno image came to mind as I walked apprehensively through this purgatory of people, fires, mysterious darkness, and loud, sensual music. Just like Hanno, scared by "fires and strange music."

David asked a passing man where we might find some food. He stared at us for a moment, then waved toward a passageway which led inside the market. The four of us followed David in dumb procession. I kept a hand on my beltpack. We stopped at a few kiosks while David asked if there was any food available. They all shook their heads, so we turned back and wandered down a narrow rutted street, a single weak streetlamp making it seem all the darker.

At the Park Hotel, another seedy-looking building of cinder block and wrought iron, we were sent up an outside stairway to a small empty dining room. We sat around an oilcloth-covered table and admired the peacock-blue walls decorated with posters of bodybuilders, "WORLD SUPERSTARS '89." (In 1988!) Naturally, banal comments were made about grotesquely overdeveloped bodies.

Another poster drew my attention: a cartoon figure of a woman in

profile, with her lips padlocked shut. But it wasn't a joke!

______________________________

Keep Our Secrets Tight

There would be the greatest peace on earth

When on every bad mouth a padlock is hung

Do you want a long, good life, then watch

your tongue and keep your lips from gossips and lies.

______________________________

On another wall, a chalkboard listed the menu, but chicken and rice were the only recognizable offerings among the unknown names. I wondered about fufu, ugali, and ndole, and Leonard wondered about a beer. Elsa brought out some photographs of her grandchildren and passed them around, while Annie made a sketch of the girl with the padlocked lips. Our voices reverberated in the bright room. No one appeared to take our order.

Finally a round-faced young fellow in a white shirt pushed through the beaded curtain and came up to the table, and David asked him in French if there was any food.

Non.

David nodded, unsurprised, and asked if we might get some omelettes. The sober-faced young man turned and left.

"Are we going to get fed?" asked Elsa.

"I think so," David said, "maybe he's gone to buy some eggs." The adjacent kitchen suddenly came alive, and in a few minutes the round-faced waiter brought us spicy omelettes, bread, and hot water for tea, chocolate, or Nescafé. A plain but satisfying meal, and now it was time to head back to the Airport Hotel for the next big event: sleep.

Our "air conditioner" chugged all night like a diesel, but had no effect on the temperature, though it almost overwhelmed the bass drum throbbing through the walls from the bar downstairs. The room contained only one droopy little bed, and David and I ceded it to Leonard, spreading our sleeping bags on the grimy floor. David said, "I often find the floors in Africa are more comfortable than the beds anyway."

I lay in the humid dark holding that thought, a symbol for the conflicting responses I had felt that day. On one level I was painfully aware of lying on a dirty floor; but on another level I realized that I was lying on a dirty floor in Africa. On that level I was excited, looking forward to a whole month of adventures to come. But deep down I realized that a month can be a long time.

Chapter 2 - Dance Party

By 6:30 a.m. we were back on the bicycles, climbing with the sun up a long hill. Sometimes it is just as well to go directly from sleep to a struggle like that, as a sleep-dulled brain seems less impressed by effort. The world was green and the sky translucent in the haze. Moon-faced people turned to stare as I pedaled by them; children walked in groups on their way to school, carrying satchels and books, and serious-faced women walked with erect carriage and easy grace, a posture endowed by the large baskets and bundles many of them bore on their heads. Men sauntered along the roadside, strolled across between the speeding minibuses and taxis to greet each other, or simply stood around, proving what is said about Women doing eighty percent of the work in Africa.

The minibuses and taxis were crammed so full that the passengers' shoulders flattened against the windows as they sped by, and all the buses carried signboards on their roofs, slogans painted in circus red and yellow: "Take Care Men," "Say What You Like, God Loves Me," "James Bond 007," "A Disappointment Is a Blessing."

After two steep miles the village of Mutengene sprawled over the crown of the hill in rows of wood and corrugated-metal houses. Leaning our bikes against a yellow building decorated with signs advertising Delta cigarettes, we took stools at the lunch counter outside. In the swept yard beside us a woman sat on a stool by a fire, dropping balls of dough into hot oil to make beignets, dumplings of deep-fried bread. Two small children played in the dirt beside her, the older girl sometimes glancing over at us, then turning away. Once I caught her eye and smiled, and she laughed and hid her face.

"I was arrested here once," David said. "You remember back there we saw a building called the 'ETS MEN'S WORK'? Then just after it the 'WOMEN'S OWN CLUB'? Well, I stopped to take a photograph of that, and a policeman came and arrested me and took me to the station. He said there was a bare-breasted woman in the background of the picture, but I sure never saw her!"

Leonard laughed: "Not likely to miss a thing like that, hmm?"

Elsa and Annie gave him an eloquent look, while I turned to David: "Touchy about that sort of thing, are they?"

"I guess. They kept me there for about two hours, and finally took the film out before I got my camera back."

Leonard's eyes crinkled behind his glasses as he turned to David. "Yeah, remember last year in Kenya when that girl Denise took a photo of the Kenyan flag and got arrested?" He turned to the rest of us. "They kept her for hours too, and took the film away. She tried to tell them she would get it developed and send them the negative, but they kept saying 'No, no, we will develop,' and then they phoned Nairobi to find out what 'develop' was." Leonard shook his head slowly and laughed.

Leonard's eyes crinkled behind his glasses as he turned to David. "Yeah, remember last year in Kenya when that girl Denise took a photo of the Kenyan flag and got arrested?" He turned to the rest of us. "They kept her for hours too, and took the film away. She tried to tell them she would get it developed and send them the negative, but they kept saying 'No, no, we will develop,' and then they phoned Nairobi to find out what 'develop' was." Leonard shook his head slowly and laughed.

"You've got to be really careful with your camera," David went on. "Many people here don't like to have their pictures taken by foreigners, and they often think you only take pictures that will embarrass them, show them at their worst and sensationalize their poverty. I remember in Liberia once, I wanted to take a photo of a family, but they waved me to 'wait, wait,' then ran off and dressed up the children, and returned to pose for me, each of them with a hand on their radio!"

"So it's not so much a religious thing here," I said, "not like those people who think you're stealing their souls?"

"No, more of a cultural thing. They just don't trust cameras."

"Hear! Hear!" I agreed.

After omelettes and Nescafé we moved down to the bikes, which were stacked against each other so that none could be reached until Annie's was out of the way. Yet she stood to the side, pushing her thick hair under her helmet and looking expectant, then moving her hands as if she wanted to help but didn't know what to do: "So...um... should we get going?"

David spoke up: "Well, no one's going anywhere until you move your bike!"

"Oh yeah ... um ... right ... heh-heh," and she took hold of the handlebars and pushed it away.

David turned to me, smiling and shaking his head. "It amazes me how many times I go through this on tours. Sometimes it takes people weeks to figure that out."

It was to be our shortest day of cycling for a month, a mere twelve miles to the coastal town of Limbe, so we set a relaxed pace through the lush plantations and Hawaiian-postcard hills. Pied crows flapped lazily over the road, while the kites soared in high circles. Mount Cameroon was a constant shadow on the right, its great bulk veiled by haze and clouds. A few villages sprouted among the trees, but they seemed to grow into the forest rather than out of it. Wooden structures were under constant attrition from dampness, insects, and mossy growths; the planked walls were weathered gray, the corners disintegrating, and even the metal roofs were dull brown under a patina of lichen and rust.

We continued along the coastal plateau, Annie out front and one of us always staying back to ride "sweep" with Elsa. We had such a short distance to travel that I felt no pressure to arrive, which on longer journeys always weighs heavily on me, and I pedaled along with a light heart. Sometimes I even sang a little, when no one was close enough to hear. My singing is best kept to myself.

We coasted in a line down a two-mile hill, feet motionless on the pedals and bodies bent into the wind, drifting around sweeping bends between the trees and unable now to wave at the faces calling out from the roadside. Snatches of distorted music from radios and tape players blared suddenly, then fell behind. We passed under a yellow railway bridge with "WELCOME TO LIMBE" painted across it, as the road leveled out and we began pedaling again, past rows of houses. Straight ahead was the Atlantic Ocean, a swath of ultramarine glittering in the morning sun. Though it was still only 9:00, the heat was already a dense curtain; no fresh breeze blew from the sea.

We circled a roundabout and turned into a side street, then wove through the narrow, neat streets of Limbe. David stopped in front of an official-looking two-story white building, and we parked our bikes against the wall. A sign read "Mairie" - town hall.

"Just wait here a minute," David said. "I'm going to see if we can meet the mayor."

He pulled a pair of plastic warm-up pants over his shorts, then spoke to one of the policemen standing by the doorway, asking for the mayor's office. One of them pointed inside.

I noticed that the policemen spoke English, and realized that we were now in the English-speaking part of the country. At independence some of Britain's slice of Cameroon went to Nigeria, but a narrow corridor remained, a remnant of British colonial rule with a few token Briticisms like language, school system, and sliced white bread. True, no baguettes here, and as we traveled around Cameroon the bread would always be the clearest sign of what language the local people might speak.

The mayor agreed to see us, so the girls wrapped their skirts over their shorts, while Leonard and I dug out our long pants. We mounted the stairs to a small meeting room, chairs placed in rows around the walls.

The mayor emerged from another door, a short, round man dressed in a close-fitting outfit of shirt-jacket and pants in a matching light brown polyester, the classic leisure-suit uniform of the West African functionary. He stepped forward to greet us with a friendly smile and a firm handshake, then motioned us to take a chair. He remained standing, his bulk rocking a little from side to side as David described where we'd been and where we were going, and he nodded and smiled with interest. When he learned that most of the group was American, the mayor mentioned that he had gone to school in the U.S. at, of all places, the University of Wisconsin. David asked about an ambulance which was being presented to Limbe by its sister city, David's hometown of Seattle. The mayor told him that he expected it to arrive in a month or so, and that he would be meeting the American delegation at that time. David wanted to know where he would have them stay.

"At the Atlantic Beach Hotel I think. It is the best in Limbe. You will stay there?"

David looked uneasy: "Well, maybe."

And there the conversation faltered, as everyone nodded and smiled in the sudden silence, the mayor still swaying from side to side uncomfortably. "I am just taken aback at your visit. I am taken aback."

The four of us smiled and nodded some more, the smiles becoming frozen and the nods becoming vacuous; then David finally rose to say goodbye. The rest of us were on our feet in a second, as the mayor smiled with renewed vigor and shook our hands again. "Perhaps I may see you at the Atlantic Beach Hotel later for a drink?"

"Yes, certainly," said David, "that would be nice," and we smiled some more and thanked the mayor for his time as we headed down the stairs. As we put away long pants and skirts and remounted the bikes, David gave a short laugh, "Well, I guess I'm trapped into the Atlantic Beach Hotel now. I wish he hadn't said that."

"Why, what's the problem?" I asked. "Isn't it any good?"

"Oh no, it's a nice hotel all right," he trailed off, and I understood. It might be a bit rich for our budget. The Bicycle Africa tours were designed to operate with a minimum of about eight people, so our little group was a strain on David's finances - as he put it, "not to lose too much."

We pedaled slowly along the sun-baked streets toward the water, then turned along the seawall and stopped at a life-size statue of a man. ALFRED SAKER, said the inscription, and I had read that he was the English missionary who founded Limbe. In the 1850S he arrived on the island of Fernando Po, a Spanish territory just off Cameroon's coast, where he worked with a group of Jamaican priests among freed slaves who had taken refuge there. The local Jesuits, appalled at the presence of Protestants on "their" island, forced the governor to expel these hardworking heretics, and Saker moved his people to the mainland. There he proved himself to be one good missionary. He bought a stretch of waterfront property from the chief of the local Douala tribe - didn't take it, bought it - cleared the land, built a school, and taught the local boys carpentry, printing, brick-making, and medicine. He learned the Douala language and translated grammar books and the Bible, built a sugar mill, and introduced breadfruit, pomegranates, avocados, and mangos. The next day, one presumes, he rested. Saker's mission grew into the town of Victoria, named by this loyal Brit for his sovereign, but was renamed Limbe in the 1970S under the continent-wide movement for Africanization. Limbe has become a busy seaside market town and a popular weekend escape from Douala, but unfortunately its future as a resort is threatened by the presence of one of the largest oil refineries in West Africa, which pours its waste directly into the sea to come washing up on the beaches.

At the edge of town we crossed a bridge over a small river, just where it emptied into the ocean, and I smiled at the shouts and laughter of a crowd of children playing in the water, escaping the heat in time-honored, international style. On the other side of the bridge, upriver, a herd of long-horned cattle browsed on the tender grasses in the shallows. We parked our bikes at the Atlantic Beach Hotel, a low white building with blue-trimmed windows and terraces amid coconut palms and bushes of frangipani and hibiscus. A swimming pool and a pair of blue gazebos faced the sea, where a row of tiny islands poked up from the blue Atlantic like rocky fingertips.

Everyone was soon occupied with washing, resting, or doing laundry, so I cycled alone back along the shore, where a beach curved around the wide bay, and stopped to admire the view. A few tall wooden fishing boats, with outboard motors set into square holes in the stern, nodded lazily on the waves. A man worked on his motor, bent over it above the water, his dark sinewy arms shining in the sun. A long skeleton of twisted iron grid work ran out from shore, the remnants of a pier from colonial days now useless and rusting. Dugout rowboats were pulled high on the beach, up to the pavement where I had stopped, and men carried baskets of fish from the boats to a line of brightly clothed women who sat along the curb, bending forward as their hands stirred through the baskets, sorting brown crabs and trout-sized silver fish. Sharks and barracudas were carried one at a time over to a small white ice-house.

I was determined to take a photograph of this colorful scene, but I knew I had to be careful. I didn't want to cause a colorful scene. I stood casually by the ruins of the pier, looking everywhere but at the "fishwives." My camera dangled carelessly at my side as I pretended to watch children playing in a schoolyard across the road. I whistled a tuneless tune. When the moment came, and the women all seemed to be looking the other way, I brought the camera up, quickly pushed the shutter, then turned away to my bike.

But I was caught. An irate voice called out: "Why you snap people dem?"

And I looked back to see an angry woman facing me, and a murmur of unrest sweeping through the others. Then again, "Why you snap people dem?"

Like Hanno, I ran away, climbed on my bike, and pedaled swiftly down the road, feeling embarrassed and ashamed. The picture didn't come out either. I'd brought the camera up so quickly that the wrist strap flew in front of the lens. Justice was served.

I took shelter in the crowds at the open-air market, pushing my bike along the rows of metal-roofed tables and kiosks selling fruits, vegetables, meats, rice, and fish, and then an outside perimeter of stalls which sold tools, dishes, buckets, and shoes. Hundreds of rolls of cloth stood on end, the bright-colored prints which were the raw material for the long skirts, pagnes, and headscarves which the women wore. I stood by and watched the bargaining, counting the money changing hands to see how much the locals were paying, then stepped in and made a deal for a nice crimson and dark green pattern. It would serve me well as a bed sheet, dressing gown, a mat for siestas, and a useful souvenir.

Two conspicuously pale figures appeared in the crowd, Annie and Elsa, who were also shopping for pagnes, as a solution for the modesty problem. Since they were expected to cover their legs whenever they were off the bikes, a pagne could simply be wrapped around their shamefully exposed nether limbs, rather than pulling on skirts or long pants.

We regrouped for lunch on the hotel terrace, overlooking the palms and rocky shoreline. Crab claws, an excellent salad, fresh fish, pineapple, good strong coffee. We couldn't know that it was the last taste of luxury and ease we would enjoy for many days, but I had experienced enough cycle touring to know that when you're finished pedaling by 9:30 in the morning, with the rest of the day free and a nice hotel by the ocean, you should enjoy it. We brought our books to the row of chairs by the water, where low tide exposed the sharp volcanic rocks. A paved walkway led into the warmest sea I've ever felt, protected from waves and currents by a low seawall. Didn't know then about the oil refinery.

David had admired my close-shaven haircut, and asked if I'd cut my hair off for this trip, or "Is it just a crazy rock 'n' roll hairstyle?" I laughed and told him I always cut my hair short before a bike tour - one less thing to worry about. He decided that was a good idea, and convinced Leonard to give him a trim. While Leonard stood behind David's chair, clipping away at his curly mass of hair, Annie, Elsa, and I sat beneath a blue gazebo, our faces buried in our books. I had packed only two books for this trip, as I seldom do much reading on a cycling tour, but they proved to be good choices. One was Aristotle's Ethics, and the other Dear Theo, the letters of Vincent van Gogh to his brother.

Aristotle was perfect in the daytime, his clear and rational discussions of virtuous behavior and the "golden mean" a welcome diversion while I lay in the shade of a tree during a midday siesta. Vincent's more romantic flights of artistic struggle suited the warm nights, as I lay back in my sleeping bag with a flashlight on my shoulder. That afternoon by the sea, while Annie began a sketch of Mister Leonard's waterfront beauty salon, I decided I wasn't ready for Aristotle yet, and between dips in the water I waded into the unpromising first chapters of Dear Theo.

Poor Vincent. An impoverished and confused young man, he gives up a position with his uncle the art dealer, with no regrets on either side, and then wanders destitute around London for a time. I happen to know, autobiographically, that if there is a good place to be destitute, it is not London.

Then Vincent tumbles into a morass of religion, and his letters begin to peal with the tiresome piety of a new believer. Deciding that evangelism is his true calling, but unable to get himself ordained, he retreats to a sad little mining town in Belgium and stews there for a while, dejected, rejected, and supremely miserable.

I, on the other hand, was supremely happy. I put down the book and lay back on a chaise longue, looking up at the sky. So many levels of movement: swallows and crows arrowing over the water, low clouds bulging swiftly across the sky, and above them the high, thin clouds riding a slow jet stream. In between, the frigate birds stretched their boomerang-shaped wings and soared on the thermal updrafts; the gentle wind blended flowers and saltwater. A freighter moved slowly across the horizon, out beyond the chain of tiny islands, the rocky fingertips. Fishing boats bobbed on the waves closer in, or motored across the bay in distant silence. I lay back in the late afternoon sun, its healing warmth on my face.

After the swift performance of sunset over the Atlantic, which I appreciated in the proper fashion, from the bar's terrace, with a Scotch on the rocks, and the lazy rhythm of the surf, we went in search of a dinner that would be a little less expensive, and a little more "cultural," than the Atlantic Beach Hotel. We walked tentatively down unlighted streets, Leonard and I trying to cover everyone's path with our flashlights.

Fugitive washes of light from the low buildings caught moving silhouettes, or played on faces and ghostly clothes. The five of us were equally masked in darkness, and for once attracted little attention.

David led us to a "chophouse," as he called it, and we passed through a lacy curtain into a low, dimly lighted room and seated ourselves around a plank table. A massive woman emerged from a back room to ask us what we wanted. David asked her what she had, but the answer made no sense to the rest of us, so we agreed to let him order a "special meal" for us.

I had read about a West African dish called fufu and was eager to try it. I didn't know what it was, but I liked the name. It turned out to be lumps of pounded maize, a cold, doughy mass reminiscent of Play-doh. We broke off pieces with our fingers and dipped them into a spicy meat broth with chunks of beef (I think). This sauce could also be ladled over bowls of white rice, a combination we would encounter many times, and which I christened "rice with junk on it." In Third World countries, poverty is the mother of invention.

The next day's ride took us up to Buea, a small town perched high on the shoulder of Mount Cameroon. Because of its pleasant highland climate, Buea had been the capital of the German colony, and it remained a favored spot for missionaries to ply their trade. David told us there were more churches around Buea than he'd seen in any other place in West Africa. I wouldn't have thought missionaries chose their missions according to climatic comfort, but I did notice that low-lying swampy villages had been deemed less in need of "saving" than were the pleasant highland locations. To be fair, though, the early missionaries had often perished from yellow fever and malaria, diseases of the tropical lowlands.

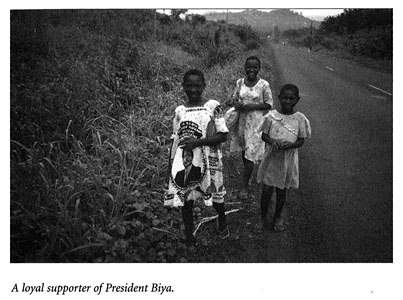

Our route from Limbe and the sea took us back up the long hill and through the Hawaiian-postcard landscape. Children waved and smiled at us on their way to school, and three young girls shyly allowed me to take their picture. All of them had their hair trimmed very short, and wore cotton dresses and rubber flip-flops. One girl's dress was printed with an almost life-size black-and-white portrait of President Paul Biya. I was to see quite a few of these patriotic dresses, and even some that portrayed Pope John Paul. I tried without success to visualize a Canadian woman wearing Brian Mulroney.

A sloppy-looking youth leaned out into the road and shouted at David, "Hey, give me something from your pack!"

David replied, reasonably enough, "Well, what do you need?"

"Whatever you have!"

We laughed and rode away.

As we pedaled by five little boys, one of them held up a big crawfish, greenish-brown, shiny, and very alive. The boys all started yelling at us in a confusion of shouts, each one of them now waving a slowly gyrating crustacean. "Voodoo," I thought to myself.

Another group of children stood at the side of the road clapping their hands in rhythm and chanting "Bicycle rider try your best! Bicycle rider try your best!" and jumping up and down in excitement as we wheeled by. David explained this as another legacy left by the French, the popularity of bicycle racing. The children were used to cheering for the racers.

As if in proof of this, a pair of local racers came charging up to Mutengene, where we sat resting at the side of the road. In answer to our wave of greeting, the two cyclists pulled up beside us, and David and I spoke with them as well as our limited French allowed. One of them was unmistakably the leader, not only because he did all the talking, but because he rode a sophisticated racing machine with all the latest gear - aerodynamic brake levers, cables routed through the frame, clip-in pedals - and he wore colorful Lycra cycling clothes. His partner's bike was less state-of-the-art, and his clothes were plain old cotton. He would be what is called a domestique, one of the members of a racing team who is responsible for helping the team's strongest rider to win by engaging in tactical duels with other racers, or letting the number one rider take it easy in his draft, to conserve his strength for a sprint at the finish. These two were training for a stage race up in Algeria, and their morning's training ride had taken them over the same route we had followed, though they covered

in a few hours what had taken us three days.

We turned straight up the side of the mountain; it would be a ten-mile climb to Buea. I was grateful for the overcast, but the heat was rising in my muscles and my face. I blew out hard to spray the tickles of sweat off my nose. Just behind me Elsa groaned out loud, muttering, "Doesn't he know anything but hills?"

Guessing she meant David and not God, I laughed over my shoulder, "Well, I don't think he made it this way!" but she was silent. On a climb like that there was no question of riding at "anyone Elsa's" pace. It's just as difficult to ride slower than your own rhythm as it is to ride faster, so everyone spread out. I was out of the saddle with my hands over the brake hoods, rocking the bike from side to side and using my weight on the pedal strokes. I noticed that David up ahead was more of a "spinner," sitting down and pedaling at a higher cadence in a lower gear. Better for him, I knew, and more aerobic, but I'd become comfortable doing it the "wrong" way.

A few buses sped by, with names like "Air Chariot" and "Justice," and as usual on a long climb, there was time to look around. Everything was greener and more lush in the shadow of the mountain. Royal palms speared up to the sky amid cedar-like evergreens with the pretty name of casuarina. Even the power lines were hung with garlands of mauve and white flowers. Framed among the leaves at the roadside, a man hacked at a tree with his machete. In another yard a man worked under the hood of an ancient Peugeot, which looked as if it had been parked in front of his house for a long time. As I slowly climbed past him, he sang out "I want to be a white man!" then chuckled without malice. What could I do but laugh?

A little higher up the mountain, I noticed a sign in front of a tumble-down house:

PROFESSOR JEROME NGWA

SPIRITUAL HEALING HOME

Specialist in -

MADNESS, GASTRIC PAIN, HEART PAIN, STOMACH ACHE,

PILE, STERILITY, WITCHCRAFT, POISON,

YELLOW FEVER, EPILEPSY, RHEUMATISM, ETC.

And these claims of Professor Ngwa's were modest. Some of the other "herbalists" promised to cure more than madness and witchcraft - even cancer and AIDS. On a later trip to Ghana, I saw this sign at the roadside:

OHEAKOH HERBAL TREATMENT

CLINIC AT NUNGUA

IMPOTENCE

Are you IMPOTENT?

You will recover from IMPOTENCE

Within 5 to 10 minutes

a) IF your PENIS is lacking sufficient STRENGTH in SEXUAL

b) IF your PENIS is WHOLLY lacking in SEXUAL POWER

VENEREAL DISEASES

If you feel WAIST PAINS and there is LIQUID

Coming from your PENIS or VAGINA

If you feel PAINS and there is BLOOD

Coming from your PENIS or VAGINA

INFERTILITY

WAIST PAINS LUMBAGO BLINDNESS

ASTHMA NERVOUSNESS PILES

HYPERTENSION STROKE FITS

RHEUMATIC PAINS GOUT

SICKLE CELLS ABDOMINAL PAINS

DIABETES MADNESS

CANCER SKIN DISEASES

URINAL TROUBLES

GOOD TREATMENT ASSURED -> AIDS DISEASES

And lots and lots of SICKNESS You can consult me for HELP

Though it is hard not to smile at these claims, some of the traditional African cures, like those in China, have proved effective, though perhaps not against cancer or AIDS. The power of faith in healing is undeniable as well, and it is partly for this reason that the missionary doctors dislike these "fetish doctors." The conflict of faiths. Science and superstition alike are aided by the patient's faith in them, and the opposing practitioners are jealous of that faith.

In Togo I once visited an American doctor, a Baptist missionary, who had constructed a remarkable hospital in the West African bush. With good old missionary zeal and hard work, backed by churches in Michigan and Indiana, he had assembled two operating rooms, twenty-five beds, an air-conditioned dispensary, and even an old M*A*S*H* X-ray machine, all powered by generator. The doctor told us that when the local people thought their relatives were about to die in the hospital, they hurried to get the patient home because the taxi fare for a corpse was ten times that for a live person, but when we discussed the fetish doctors, his face hardened. He told us he had just witnessed the funeral of an evil fetish priest, and the villagers had carried the body along in a stretcher, beating it with sticks, then dumped it into a grave of thorns, so the priest would have to sleep in pain forever. When asked if he allowed the village doctors to visit his patients in the hospital, the doctor's response was surprisingly vehement. "No, we don't. They do the work of Satan, and we're trying to do the work of God."

Africans tend to be pragmatic, and are still likely to consult both kinds of doctor, and magician, like a businessman I know who remains open to all religions, "just in case they're right." And, like elsewhere in the world, there seems to be a relationship between faith and the difficulty of life. For example, independence has been tougher on Ghana than Cameroon. The Ghanaian people have suffered radical governments, regular coups, and the corresponding economic chaos, while faith seems stronger and more serious there. Judging by the roadside signs, many more traditional doctors practice in Ghana; there are definitely more churches, and even the minibus signs reflect the harsher life. You see no frivolous ones in Ghana, no "Air Chariot" or "James Bond 007." All the Ghanaian buses have devotional names like "Blessed Assurance" or "Good Father." No sense of humor - just like faith. You could sometimes say reason is a luxury everywhere in the world. It works fine as long as life is reasonable, but when guns, poverty, and drought start pushing people around, they often retire into faith.

And if you're going to retire into faith, go to Buea. Missionaries may be crazy, but they're not stupid. When David and I panted up the mountainside to the cool and healthful air of Buea, the road was lined with one church after another: Baptist, Catholic, Lutheran, Methodist, I don't know what all. Sweating and breathless, we finally stopped at a crossroads, and I sat on a bench to wait for the others while David went off in search of a hotel.

Leonard and Annie hauled themselves slowly up to me, and wilted into the shade. Then came a vision: Elsa being pushed up the hill by a young guy who trotted behind her. We laughed and ran for 'our cameras as Elsa coasted up saying, "I didn't mind that a bit!"

Her "pusher" stopped to talk with us, and we soon discovered that he could be pushy in more ways than one. Chifor Ignatius was his name, a skinny young man in a baggy white shirt and dark trousers. His eyes were sharp and guarded, and did not inspire trust in me.

He started right in on Elsa. "Will you give me your address so I may write to you? I meet many people who say they will write, but nobody is ever writing back to me."

A common syndrome in Africa, especially in countries like Ghana, where every second person wants your address. Bad feelings are often caused by foreigners who promise to send photographs and letters to friends made in the glory days of a vacation, but then return home to the work-a-day world and forget all about it. I'm sure many would rationalize it: "Well I just wanted to be friendly. Maybe I'll get to it sometime." But of course to the people they disappoint, it's just another broken promise. Then again, offering your address can be an invitation to requests for money, a television set, an airline ticket, or one day you may find your forgotten African friend at your door.

Once in Ghana I had stopped at a roadside bar for a Coke, and a young man came up to me, pushing through the children who had gathered around to stare. He sat down in front of me and immediately demanded my address and wanted me to write to him. He explained that he was ambitious, and as proof he pointed around at my bicycle and my camera. "Someday I will have one of those. And one of those." He was very plain about what he wanted with me; he pushed his baseball cap back on his head and leaned forward to say, "All I need is a white man to help me."

I could only laugh, but I have found this approach and this attitude to be all too common among Africans, especially the youth. They see a white man as a ticket to something; they think every white man holds the power to make things happen. Sometimes you tell an African that you're bicycling around his country, and at first he's amazed; but then he thinks again, waves his hand, and says, "Well, it's easy for a white man."

Many young Africans have discussed their ambitions with me, and not one of them has ever talked about doing things, but only having things. They never spoke of wanting to be a doctor or an architect; they just wanted to go to America and get rich. The limited view, unfortunately, of too many Westerners as well - the idea that the goal of life is to get things, like on a game show. When life-support is on the line, money is everything, but beyond that threshold of survival life ought to get bigger. Or am I too idealistic? Perhaps. But thus have many young Africans inherited the Western curse of acquisitiveness, without the accompanying drive for accomplishment. They dream of having, not doing. And a white man can help them.

Elsa moved away from Chifor Ignatius, and the four of us had a quick, whispered huddle. We agreed that we didn't really want to take the responsibility of saying we would write to people like Chifor Ignatius who barely crossed our path, but we wanted to be diplomatic as well. Elsa finally gave him a few coins for pushing her, took down his address, and promised to send him a postcard.

Then he approached me. "You were snapping a photograph of me pushing the lady."

I knew he wanted either a copy of the picture, or to be paid for being in it, so I put him off firmly. "It wasn't a picture of you, it was a picture of her. You were behind her."

He looked doubtful. "I am not in the photograph?"

"It was of her." This careful response was true, if equivocal, and ended the discussion. When the photograph was developed, he did appear, sort of, as a white-shirted shadow in the background.

David returned and led us to a three-story tenement of whitewashed concrete, the Parliamentarian Flats Hotel. I had to learn the impressive name from a giant fob on the room key, as there was no sign at all in front of the building. The man at the desk told us he was waiting for a new sign, which had been promised to him by a brasserie - brewery.