|

THE NOVEL (Preview) by Kevin J. Anderson from a story and lyrics by Neil Peart © 2012 |

Click Any of the Following Images to Enlarge

A remarkable collaboration that is unprecedented in its scope and realization, this exquisitely wrought novel represents an artistic project between the bestselling science fiction author Kevin J. Anderson and the multiplatinum rock band Rush. The newest album by Rush, Clockwork Angels, sets forth a story in Neil Peart's lyrics that has been expanded by him and Anderson into this epic novel. In a young man's quest to follow his dreams, he is caught between the grandiose forces of order and chaos. He travels across a lavish and colorful world of steampunk and alchemy with lost cities, pirates, anarchists, exotic carnivals, and a rigid Watchmaker who imposes precision on every aspect of daily life. The mind-bending story is complemented with rich paintings by the five-time Juno Award winner for Best Album Design, Hugh Syme.

Dedication:

who are just beginning all the journeys of a great adventure

Acknowledgments:

Many people helped us create this story, the world, the characters, and the words that convey it all.

Special thanks go to Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, Hugh Syme, Pegi Cecconi, Bob Farmer; Rebecca Moesta, Louis Moesta, Deb Ray, Steven Savile; Jennifer Knoch, Jack David, David Caron, Erin Creasey, Sarah Dunn, and Crissy Boylan at ECW; and John Grace at Brilliance Audio.

Table of Contents

PROLOGUE

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

AFTERWORD

PROLOGUE: Time is still the infinite jest

It seems like a lifetime ago - which, of course, it was . . . all that and more. A good life, too, though it didn't always feel that way.

From the very start, I had stability, measurable happiness, a perfect life. Everything had its place, and every place had its thing. I knew my role in the world. What more could anyone want? For a certain sort of person, that question can never be answered; it was a question I had to answer for myself in my own way.

Now that I look back along the years, I can measure my life and compare the happiness that should have been, according to the Watchmaker, with the happiness that actually was.

Though I am now old and full of days, I wish that I could live it all again.

Yes, I've remembered it all and told it all so many times. The events are as vivid as they were the first time, maybe even more vivid ... maybe even a bit exaggerated.

The grandchildren listen dutifully as I drone on about my adventures. I can tell they find the old man's stories boring - some of them anyway. (Some of the grandchildren, I mean . . . and some of the stories, too, I suppose.)

When tending a vast and beautiful garden, you have to plant many seeds, never knowing ahead of time which ones will germinate, which will produce the most glorious flowers, which will bear the sweetest fruit. A good gardener plants them all, tends and nurtures them, and wishes them well.

Optimism is the best fertilizer.

Under the sunny blue sky on my family estate in the hills, I look up at the white clouds, fancying that I see shapes there as I always have. I used to point out the shapes to others, but in so many cases that effort was wasted; now the imaginings are only for special people. Everyone has to see his own shapes in the clouds, and some people don't see any at all. That's just how it is.

In the groves that crown the hills, olive trees grow wherever they will. From a distance, the rows of grapevines look like straight lines, but each row has its own character, some bit of disorder in the gnarled vines, the freedom to be unruly. I say it makes the wine taste better; visitors may dismiss the idea as just another of my stories. But they always stay for a second glass.

The bright practice pavilions swell in the gathering breeze, the dyed fabric puffing out. That same gentle wind carries the sounds of laughing children, the chug of equipment being tested, the moan and wail of a calliope being tuned.

While preparing for the next season, my family and friends love every moment - isn't that the best gauge of a profession? My own contentment lies here at home. I content myself with morning walks along the seashore to see what surprises the tide has left for me. After lunch and an obligatory nap, I dabble in my vegetable garden (which has grown much too large for me, and I don't mind a bit). Planting seeds, pulling weeds, hilling potatoes, digging potatoes, and harvesting whatever else has seen fit to ripen that week.

Right now, it is squash that demands my attention, and four of my young grandchildren help me out. Three of them work beside me because their parents assigned them the chores, and curly haired Alain is there because he wants to hear his grandfather tell stories.

The exuberant squash plant has grown into a jungled hillock of dark leaves with myriad hair-fine needles that cause the grandchildren no small amount of consternation. Nevertheless, they go to war with the thicket and return triumphant with armloads of long green zucchinis, which they dump into the waiting baskets. Bees buzz around, looking for blossoms, but they don't bother the children.

Alain braves the deepest wilderness of vines and emerges with three perfect squash. "We almost missed these! By the next picking, they would have been too big."

The boy doesn't even like squash, but he loves seeing my proud smile and, like me, takes satisfaction in doing something that would have gone undone by less dedicated people. He feels he has earned a reward. "Tonight could I look at your book, Grandpa Owen? I want to see the chronotypes of Crown City." After a pause, Alain adds, "And the Clockwork Angels."

This is not the same book that I kept when I was a young man in a small humdrum village, but Alain does have the same imagination and the same dreams as I had. I worry about the boy, and also envy him. "We can look at it together," I say. "Afterward, I'll tell

you the stories."

The other three grandchildren are not quite tactful enough to stifle their groans. My stories aren't for everyone - they were never meant to be - but Alain might be that one perfect seed. What more reason do I need to tend my garden?

"The rest of you don't have to listen this time," I relent, "provided you help scrub the pots after dinner."

They accept the alternative and stop complaining. How can this be the best of all possible worlds when doing the dishes seems preferable to hearing tales of grand adventures? Of bombs and pirates, lost cities and storms at sea? But Alain is so excited he can barely wait.

Adventuring is for the young.

Ah, how I wish I were young again. . . .

Chapter 1:

In a world where I feel so small I can't stop thinking big

The best place to start an adventure is with a quiet, perfect life . . . and someone who realizes that it can't possibly be enough.

On the green orchard hill above a sinuous curve of the Winding Pinion River, Owen Hardy leaned against the trunk of an apple tree and stared into the distance. From here, he could see - or at least imagine - all of Albion. Crown City, the Watchmaker's capital, was far away (impossibly distant, as far as he was concerned). He doubted anyone else in the village of Barrel Arbor bothered to think about the distance, since only a few had ever made the journey to the city, and Owen was certainly not one of them.

"We should get going," said Lavinia, his true love and perfect match. She stood up and brushed her skirts. "Don't you need to get these apples to the cider house?" He would turn seventeen in a few weeks, but he was already the assistant manager of the orchard; even so, Lavinia was usually the one to remind him of his responsibility.

"We should get going," said Lavinia, his true love and perfect match. She stood up and brushed her skirts. "Don't you need to get these apples to the cider house?" He would turn seventeen in a few weeks, but he was already the assistant manager of the orchard; even so, Lavinia was usually the one to remind him of his responsibility.

Still leaning against the apple tree, he fumbled out his pocket-watch, flipped open the lid. "It won't be long now. Eleven more minutes." He looked at the silver rails that threaded the gentle river valley below.

Lavinia had such an endearing pout. "Do we have to watch the steamliners go by every day?"

"Every day, like clockwork." Owen thumbed shut the pocket-watch, knowing she didn't feel the same excitement as he did. "Don't you find it comforting that everything is as it should be?" That, at least, was a reason she would understand.

"Yes. Thanks to our loving Watchmaker." She paused a moment in reverent silence, and Owen thought of the wise, dapper old man who governed the whole country from his tower in Crown City.

Lavinia had a rounded nose, gray eyes, and a saucy splash of freckles across her face. Sometimes Owen imagined he could hear music in her soft voice, though he had never heard her sing. When he thought of her hair, he compared it to the color of warm hickory wood, or fresh-pressed coffee with just a dollop of cream. Once, he had asked Lavinia what color she called her hair. She answered, "Brown," and he had laughed. Lavinia's pithy simplicity was adorable.

"We have to get back early today," she pointed out. "The almanac lists a rainstorm at 3:11."

"We have time."

"We'll have to run . . ."

"It'll be exciting."

He pointed up at the fluffy clouds that would soon turn into thunderheads, for the Watchmaker's weather alchemists were never wrong. "That one looks like a sheep."

"Which one?" She squinted at the sky.

He stood close, extended his arm. "Follow where I'm pointing . . . that one there, next to the long, flat one."

"No, I mean which one of the sheep does it look like?"

He blinked. "Any sheep."

"I don't think sheep all look the same."

"And that one looks like a dragon, if you think of the left part as its wings and that skinny extension its neck."

"I've never seen a dragon. I don't think they exist." Lavinia frowned at his crestfallen expression. "Why do you always see shapes in the clouds?"

He wondered just as much why she didn't see them. "Because there's so much out there to imagine. The whole world! And if I can't see everything for myself, then I have to imagine it all."

"But why not just think about your day? There's enough to do here in Barrel Arbor."

"That's too small. I can't stop thinking big."

In the distance, he heard the rhythmic clang of the passage bell, and he emerged from under the apple tree, shading his eyes, looking down to where the bright and razor-straight path of the steamliner track beckoned. The alchemically energized road led straight to the central jewel of Crown City. He caught his breath and fought back the impulse to wave, since the steamliner was too far away for anyone aboard to see him.

The line of floating dirigible cars came down from the sky and aligned with the rails - large gray sacks tethered to the energy of the path below. There were heavy, low-riding cargo cars full of iron and copper from the mountain mines or stacked lumber from the northern forests, as well as ornate passenger gondolas. Linked together, the steamliner cars lumbered along like a fantastical, bloated caravan.

Cruising above the rugged terrain, the linked airships descended at the distant end of the valley, touched the rails with a light kiss, and, upon contact, the steel wheels completed the circuit. Coldfire energy charged their steam boilers, which kept the motive pistons pumping.

Owen stared as the line of cars rolled by, carrying treasures and mysteries from near and far. How could it not fire the imagination? He longed to go with the caravan. Just once.

Was it too ambitious to want to see the whole world? To try everything, experience the sights, sounds, smells . . . to meet the Watchmaker, maybe work in his clocktower, hear the Angels, wave at ships steaming off across the Western Sea toward mysterious Atlantis, maybe even go aboard one of those ships and see those lands with his own eyes . . . ?

"Owen, you're daydreaming again." Lavinia picked up her basket of apples. "We have to go now or we'll get soaked." Watching the steamliners roll off into the distance, he gathered his apples and hurried after her.

"Owen, you're daydreaming again." Lavinia picked up her basket of apples. "We have to go now or we'll get soaked." Watching the steamliners roll off into the distance, he gathered his apples and hurried after her.

They made it back to the village with fourteen minutes to spare. At the end, he and Lavinia were running, even laughing. The unexpected rush of adrenalin delighted him; Lavinia's laughter sounded nervous, not that a little rain would be a disaster, but she did not like to get wet. As they passed the stone angel statue at the edge of town, Owen checked his watch, seeing the minute hand creep toward the scheduled 3:11 downpour.

The clouds overhead turned gray and ominous on schedule as the two skidded to a halt at Barrel Arbor's newsgraph office, which Lavinia's parents operated. The station received daily reports from Crown City and words of wisdom from the Watchmaker; her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Paquette, disseminated all news to the villagers.

Owen relieved Lavinia of her basket of apples. "You'd better get inside before the rain comes."

She looked flushed from exertion as she reached the door to the office. Grateful to be back on schedule, she pulled open the door with another worried glance, directed toward the town's clocktower rather than the rainclouds themselves.

With his birthday and official adulthood approaching like a fast-moving steamliner, Owen felt as if he were standing on the precarious edge of utter stability. He had already received a personal card from the Watchmaker, printed by an official stationer in Crown City, that wished him well and congratulated him on a happy, contented life to come. A wife, home, family, everything a person could want.

From the point he became an adult, though, Owen knew exactly what his life would be - not that he was dissatisfied about being the assistant manager of the town's apple orchard, just wistful about the lost possibilities. Lavinia was only a few months younger than him; surely she felt the same constraints and would want to join him for the tiniest break from the routine.

Before she ducked into the newsgraph office, Owen had an idea and called for her to wait. "Tonight, let's do something special, something exciting." Her frown showed she was already skeptical, but he gave her his most charming smile. "Don't worry, it's nothing frightening - just a kiss." He looked at his watch: 3:05, still six more minutes.

"I've kissed you before," she said. Chastely, once a week, with promises of more after they were officially betrothed, because that was expected. Very soon, she would receive her own printed card from the Watchmaker, wishing her happiness, a husband, home, family.

"I know," he continued in a rush, "but this time, it'll be romantic, special. Meet me at midnight, under the stars, back up on orchard hill. I'll point out the constellations to you."

"I can look up constellations in a guidebook," she said.

He frowned. "And how is that the same?"

"They're the same constellations."

"I'll be out there at midnight." He quickly glanced at the clouds, then down at his pocketwatch. Five more minutes. "This will be our special secret, Lavinia. Please?"

Quick and noncommittal, she said, "All right," then retreated into the newsgraph office without a further goodbye.

Cheerful, he swung the apple baskets in his hands and headed toward the cider mill next to the small cottage where he and his father lived.

More thunderheads rolled in. The day was dark. With the impending rainstorm, the town streets were empty, the windows shuttered. Every person in Barrel Arbor studied the almanac every day and planned their lives accordingly.

As Owen hurried off, sure he would be drenched in the initial cloudburst, he encountered a strange figure on the main street, an old pedlar dressed in a dark cloak. He had a gray beard and long, twisted locks of graying hair that protruded from under his stovepipe hat.

Clanging a handbell, the pedlar walked alongside a cart loaded with packets, trinkets, pots and pans, wind-up devices, and glass bubbles that glowed with pale blue coldfire. His steam-driven cart chugged along as well-oiled pistons pushed the wheels; alchemical fire heated a five-gallon boiler that looked barely adequate for the tiny engine.

The pedlar could not have picked a worse time to arrive. He walked through Barrel Arbor with his exotic wares for sale, but his potential customers were hiding inside their homes from the impending rain. He clanged his bell. No one came out to look at his wares.

As Owen hurried toward the cider house, he called out, "Sir, there's a thunderstorm at 3:11!" He wondered if the old man's pocket watch failed to keep the proper time, or if he had lost his copy of the official weather almanac.

The stranger looked up, glad to see a potential customer. The pedlar's right eye was covered with a black patch, which Owen found disconcerting. In the Watchmaker's safe and benevolent Stability, people were rarely injured.

When the pedlar fixed him with his singular gaze, Owen felt as if the stranger had been looking for him all along. He stopped clanging the handbell. "Nothing to worry about, young man. All is for the best."

"All is for the best," Owen intoned. "But you're still going to get wet."

"I'm not concerned."The stranger halted his steam-engine cart and, without taking his gaze from Owen, fumbled with the packages and boxes, touching one then another, as if considering. "So, young man, what do you lack?"

The question startled Owen and made him forget about the impending downpour. He supposed pedlars commonly used such tempting phrases as they carried their wares from village to village. But still . . .

"What do I lack?" Owen had never considered this before. "That's an odd thing to ask."

"It is what I do." The pedlar's gaze was so intense it made up for his missing eye. "Think about it, young man. What do you lack? Or are you content?"

Owen sniffed. "I lack for nothing. The loving Watchmaker takes care of all our needs. We have food, we have homes, we have coldfire, and we have happiness. There's been no chaos in Albion in more than a century. What more could we want?"

The words tumbled out of his mouth before his dreams could get in the way. The answer felt automatic rather than heartfelt. His father had recited the same words again and again like an actor in a nightly play; Owen heard other people say the same words in the tavern, not having a conversation but simply reaffirming one another.

What do I lack?

Owen also knew that he was about to become a man, with commensurate responsibilities. He set down his apples, squared his shoulders, and said with all the conviction he could muster, "I lack for nothing, sir."

Owen got the strange impression that the pedlar was pleased rather than disappointed by his answer. "That is the best answer a person can make," said the old man. "Although such consistent prosperity certainly makes my profession a difficult one."

The old man rummaged in his packages, opened a flap, and paused. After turning to look at Owen, as if to be sure of his decision, he reached into a pouch and withdrew a book. "This is for you. You're an intelligent young man, someone who likes to think - I can tell."

Owen was surprised. "What do you mean?"

"It's in the eyes. Besides," he gestured to the empty village streets, "who else stayed out too long because he had more to do, other matters to think about?" He pushed the book into Owen's hands. "You're smart enough to understand the true gift of Stability and everything the Watchmaker has done for us. This book will help."

Owen looked at the volume, saw a honeybee imprinted on the spine, the Watchmaker's symbol. The book's title was printed in neat, even letters. Before the Stability. "Thank you, sir. I will read it."

The stranger turned a dial that increased the boiler's alchemical heat, and greater plumes of steam puffed out. The cart chugged forward, and the pedlar followed it out of town.

Owen was intrigued by the book, and he opened to the title page. He wanted to stand there in the middle of the street and read, but he glanced at his pocketwatch - 3:13. He held out his hand, baffled that raindrops hadn't started falling. The rain was never two minutes late.

Nevertheless, he didn't want to risk letting the book get wet; he tucked it under his arm and rushed with his apples to the cider house. A few minutes later, when he reached the door of the cool fieldstone building where his father was working, he turned around to see that the old man and his automated cart had disappeared.

"You're late," his father called in a gruff voice.

Owen stood in the door's shadows, staring back down the village streets. "So is the rain" - a fact that he found far more troubling. A crack of thunder exploded across the sky and then, as if someone had torn open a waterskin, rain poured out of the clouds. Owen frowned and looked at the ticking clock just inside the cider house. 3:18 p.m.

Only later did he learn that the town's newsgraph office had received a special updated almanac page just that morning, which moved the scheduled downpour to precisely 3:18 p.m.

Chapter 2:

We are only human. It's not ours to understand

Bushels of apples sat in the cool, shadowy interior of the cider house, patiently ripening to soft sweetness. Owen and his father were scheduled to press a fresh half-barrel that afternoon, which would require at least three bushels, depending on how juicy

the apples were.

A flurry of ideas distracted Owen as he helped his father with the work, manning the press machinery, adjusting the coldfire to keep the steam pressure at its appropriate level. As assistant manager of the orchard, Owen had already learned every aspect of the apple business. While going about his rote tasks, he pondered the mysterious pedlar, and he longed to page through the book the man had given him. As if that wasn't enough to preoccupy his thoughts, he was even more distracted by the promise of a romantic midnight kiss from Lavinia while the stars looked down - it was like something out of an imaginary story.

His father, Anton Hardy, formed his own, entirely incorrect, explanations for Owen's daydreaming. Indicating the cider press, he said, "Nothing to worry about, son. I've trained you well. Very soon now, you'll be able to manage the orchards as well as I do, in case anything happens to me."

His father, Anton Hardy, formed his own, entirely incorrect, explanations for Owen's daydreaming. Indicating the cider press, he said, "Nothing to worry about, son. I've trained you well. Very soon now, you'll be able to manage the orchards as well as I do, in case anything happens to me."

Owen took a moment to piece together where the comment had come from. "Oh, I'm not worried." He decided it was easier to accept his father's conclusion than to tell him the truth. "But nothing's going to happen to you. Nothing unpredictable ever happens."

He glanced at the book he had set on top of a fragrant old barrel. "Thanks to the Stability."

"I wish that were so, son." A surprising sparkle of tears came to the older man's heavy eyes, and he turned away, pretending to concentrate on the hydraulics connected to the apple press. The comment must have reminded Anton Hardy of his wife; she had

died of a fever when Owen was just a child.

He'd been so young that his memories were vague, but he remembered sitting on her lap, nestled in her skirts - in particular, he recalled a blue dress with a flower print. Together, she and Owen would look at picture books, and she'd tell him wondrous legends of faraway places. Though he was now grown, he still looked at those treasured books, and often, but Owen had to tell himself the stories now, for his father never did.

Anton Hardy preserved his memories of his beloved Hanneke like a flower pressed between the pages of a book: colorful and precious, yet too delicate ever to be taken out and handled. Even though Owen knew she was dead, in fanciful moments he preferred to imagine that she had merely faked her fever so she could leave the sleepy farming town and go off to explore the wide world. "On my way at last!" He imagined her adventuring even now, and one day she would come back from Crown City or distant Atlantis, filled with amazing stories and bringing exotic gifts. He could always hold out hope. . . .

His father sniffled, muttered, "All is for the best," then topped off the fresh-squeezed cider in the half-barrel. He hammered the lid into place with a mallet.

While Anton completed a few unnecessary tasks around the cider house, Owen seated himself near one of the small windows, which provided enough light to read. Before the Stability was a compact volume full of nightmares, and the young man grew more and more disturbed as he turned the pages.

The world had been a horrific place more than a century ago, before the Watchmaker came: villages were burned, brigands attacked unprotected families, children starved, women were raped. Thievery ran rampant, plagues wiped out whole populations, and isolated survivors degenerated into cannibals. He read the stark accounts with wide eyes, anxious to reach the end of the book, because he knew that Albion would be saved, since everyone was now happy and content.

He skipped ahead to the final page, relieved and reassured to read, "And Barrel Arbor is a perfect example of what the Stability has brought. The best village in the best of all possible worlds, where every person knows his place and is content." Owen smiled in wonderment, glad to know that, despite his daydreaming, his situation here could not be better.

His father didn't ask him about the book. They shared an early supper of crisp apples (naturally), cheese from the widow Loomis, bread and a slice of fresh apple pie from Mr. Oliveira, the baker. The Hardys provided him with all the apples he needed, and in return they received regular supplies of apple pie, apple tarts, apple muffins, apple strudel, and whatever else Mr. Oliveira could think of.

The two didn't have much to talk about - they rarely did. Attuned to each other and attuned to the day, Owen and his father looked at their pocketwatches at the same time. They had finished the scheduled work and were satisfied by their casual meal. Afterward, Anton Hardy had his evening routine, and Owen tagged along. They headed for the Tick Tock Tavern.

In a small village, the most efficient way to hear the news was to listen to gossip, and the best place to get gossip was in the tavern.

Anton Hardy sat back in his usual wooden chair, drinking a pint of hard cider, while Owen sat beside him with a mug of fresh cider. Others preferred intoxicating mead made from the Huangs' honey, harvested from the town apiary that followed the standard design distributed by the Watchmaker's own beekeepers.

When Owen turned seventeen, he would switch to drinking hard cider, because that was expected from an adult. (In truth, he had already sneaked a few tastes of hard cider, even though he wasn't supposed to. He suspected his father knew, but hadn't said anything.)

As the tavern customers settled in to their routine, Lavinia's father came in with his stack of typed reports and announcements, which were delivered by resonant alchemical signal to the news-graph office. Mr. Paquette - a man who took great pride in his lavish sideburns - held a yellowish sheet of pulp paper up to the lamp of coldfire light and squinted down at the uneven typewritten letters. Conversation quieted in the Tick Tock Tavern as Mr. Paquette drew out the suspense.

He adjusted his spectacles, cleared his throat, and spoke in a voice that carried great importance. "The weather alchemists announce that this afternoon's rainshower is to be delayed by seven minutes, in order for the moisture-distribution systems to run more efficiently." He shuffled his papers, seemed embarrassed. "Sorry, that came in this morning."

Picking up the next newsgraph printout, he read, "The Anarchist planted another bomb and ruined a portion of the northern line, disrupting steamliner traffic. Fortunately, the airship captain was able to lift his cars to safety just in time, and no one was hurt." The people grumbled and made scornful comments about the evil man who was singlehandedly trying to disrupt the Watchmaker's century-long Stability. Mr. Paquette continued, "The Regulators closed in on the perpetrator just after the explosion, but he escaped, no doubt to cause further destruction."

Picking up the next newsgraph printout, he read, "The Anarchist planted another bomb and ruined a portion of the northern line, disrupting steamliner traffic. Fortunately, the airship captain was able to lift his cars to safety just in time, and no one was hurt." The people grumbled and made scornful comments about the evil man who was singlehandedly trying to disrupt the Watchmaker's century-long Stability. Mr. Paquette continued, "The Regulators closed in on the perpetrator just after the explosion, but he escaped, no doubt to cause further destruction."

"The devil take him," Owen's father said.

"Hear, hear!" Others raised their pints in agreement.

Owen drank along with them, but asked, "Why would anyone want to ruin what the Watchmaker created? Doesn't he know how dangerous the world was before the Stability?" He had known that much even before reading the pedlar's book.

"He's a freedom extremist, boy. How does a disordered mind work?"

"It's not ours to understand," Mr. Oliveira said. "I doubt the monster understands it himself."

Mr. Paquette cleared his throat loudly to show that he had not yet finished reading the news. He picked up a third sheet of pulp paper and raised his eyebrows in impatience until the muttering had quieted. "The Watchmaker is also saddened by the loss of a cargo steamer fully loaded with precision jewels and valuable alchemical supplies from Poseidon City. The Wreckers are believed to be responsible."

More grumbling in the tavern. "That's the third one this year," said Mr. Huang.

Little was known about the Wreckers, the pirates and scavengers who preyed on cargo steamers that sailed across the Western Sea to the distant port city of Poseidon. These ships carried loads of rich alchemical elements and rare timekeeping gems mined from the mountains of Atlantis, all of which were vital for the services provided by the Watchmaker.

"I'll bet the Anarchist is in league with them," Owen said. "They all want to cause disruption."

"The Watchmaker will take care of it," said Mr. Paquette with great conviction, setting aside the sheets of paper to emphasize that he was stating his own opinion rather than reading a pronouncement from the Watchmaker. "They will get what they deserve."

"But how do you know that?" Owen said in a small voice.

His father nudged his arm. "Because we believe, son - and you were brought up to believe. Everything has its place, and every place has its thing." He looked around at the others, as if afraid they would think he was a failure as a father for letting his son doubt. "And I'll believe it myself to my final breath."

Everyone agreed, louder than was necessary, and toasted the Watchmaker.

As the evening wound down, he and his father spent a few quiet hours in their cottage. Anton Hardy sat by the fire with a sharpened pencil and his ledger, going over how many barrels of fresh cider were to be delivered, how many would remain in storage to ferment into hard cider, how many were reserved for vinegar, and how much the Watchmaker allowed him to charge for each. Every villager had a role to play, and all accounts balanced.

Finished, Owen's father set the ledger aside and began reading the Barrel Arbor newspaper, which was little more than a weekly compilation of newsgraph reports from Crown City, thought-provoking statements from the Clockwork Angels, and a few local-interest stories that Lavinia's parents wrote and appended to each edition.

The current issue had an early announcement of Owen's impending birthday, to which Mrs. Paquette had added a small comment, "And we hope to have more substantial news to report on this matter soon." By tradition, of course, his betrothal to Lavinia was more than likely.

Owen had already read the newspaper and was more interested in looking at the well-thumbed volumes he had taken down from the high shelf. Reading Before the Stability that afternoon had disturbed him, but these other publications were dear to his heart, the picture books he had loved as a child: beautiful hardbound volumes with tipped-in chronotypes, color plates specially treated with a reactive alchemical gloss that gave the reader a giddy feeling of looking into the image.

First, he paged through the picture book of Crown City, dwelling on the poignant chronotype of the Angels, the most famous symbol of the Watchmaker's ordered world. Four graceful female figures installed in Chronos Square, looming high above the crowds - symbolic, yet utterly perfect, divine machines who spread their wings to dispense grace on humanity. Though he could barely remember his mother, Owen was sure that each of the four Clockwork Angels must have been molded with her face.

The second volume was even more inspiring, though none of it was real. Legends of sea monsters and mythical beasts, centaurs, griffins, dragons, basilisks . . . and imaginary places far from Albion, including the wondrous Seven Cities of Gold, collectively called Cíbola. These volumes were so old that they had been printed before the Stability; after reading about the chaotic times in the pedlar's book, he considered it a wonder that any publication had survived that turmoil.

Owen was so intent on the book that he didn't notice his father standing behind him. Anton Hardy had never forbidden his son from looking at the books, but neither had he approved of the young man's fascination.

Startled, Owen tried to close the cover, but his father reached out to stop him. In the vivid chronotype on the page, sunlight gleamed through an exotic rock formation in the Redrock Desert. Together, the two stared down at the fanciful pristine towers of intricate stone, the amazing architecture of the Seven Cities of Gold.

"These were your mother's books. And I miss her, too." Anton Hardy held his hand on the page for a long moment, staring down, but no longer seeming to see the illustration. "I miss her, too," he said again in a faint voice, barely a whisper. "Ah, Hanneke . . ." Owen had never heard such emotion in his father's voice before.

The emotion was gone as quickly as it came. "Soon enough, it'll be time to put away these books for good, lock away that part of the past. The Watchmaker says we can't make time stand still. Don't look back, but take the time to look around you now."

"But it's all we have left of Mother - these books and our memories."

"You have to look forward," Anton said. "Once you become an adult, the Watchmaker has expectations. You must put all this foolishness behind you."

Owen closed the book but kept it on his lap. In his quiet, ordered world, he'd never been allowed any "foolishness" in the first place.

His father turned the coldfire lanterns down to a comforting glow. "Time to wind the clocks." Before getting ready for bed, the two went through their ritual. Owen turned the key in the mantle clock and wound the spring; his father did the same with the kitchen clock. Owen hung the counterweight and set the pendulum swinging in the main grandfather clock. They went from clock to clock, shelf to shelf, room to room. As a final check, Owen poked his head outside and looked at Barrel Arbor's main clocktower to verify that the time was accurate and every tick was right in the Watchmaker's world.

Each night, this was time he and his father spent together, but because they took such care to maintain the clocks, they didn't actually spend the time at all: they saved it. Not one second was allowed to slip away.

When they were done and his father was satisfied, he bade Owen goodnight. "I'll stay up just a little longer," Owen said. He usually did.

Saddened by the reminder of his lost wife, his father didn't object to letting Owen look at the picture books some more.

Sitting alone, Owen's pulse raced as he thought of his planned foolishness for midnight. Only two more hours before he would slip out and meet sweet Lavinia for a stolen kiss. Although he knew it would be over in a moment, the memory would last for a long time.

After he turned seventeen and the rest of the Watchmaker's safety net wrapped around him, he would have no further opportunity to be so impetuous. He intended to make the best of it.

Chapter 3:

On my way at last

His father was quietly snoring by 10:06 p.m., but Owen wasn't sleepy at all. Even the synchronous ticking of the clocks in the house failed to lull him. Anticipation was a tightly wound spring inside.

The more he thought about it, the more surprised Owen was by his impulse. What had driven him to suggest it? In Barrel Arbor, decent people didn't sneak out at midnight. He and Lavinia were a comfortable pair who spent most days together doing their assigned tasks, compatible, clearly intended for each other in the scheme of things. None of the villagers gave a second thought to seeing him in the young woman's company, but the two were not yet betrothed, and Owen could imagine quite a scandal if anyone discovered that they were meeting in secret long after dark.

Which made the idea all the more exciting . . .

He hoped Lavinia was as captivated by the thought as he was. This daring little escapade would be something they'd both remember and pointedly not tell their children. As they grew older and settled in their lives, who would believe that reliable, predictable Owen and Lavinia Hardy had been reckless or impetuous in their youth? He laughed at the very idea that his own father might have done the same when he was young. But maybe his adventurous mother . . .

He daydreamed that Hanneke had gone off to see the world, that she had visited the Seven Cities of Gold, that she had ridden steamliners and found distant shores. Someday, maybe he and Lavinia would also run off, explore the enticing continent of Atlantis. The thought of his mother still miraculously alive, a queen of some lost country, brought a smile to his face; she would welcome her son and his beautiful wife as a prince and princess. They would feast on hundreds of types of fruit, instead of just apples!

He kept trying to imagine Lavinia traveling with him, but his thoughts wandered off. . . .

He woke with a start and saw by the ticking bedside clock that it was 11:28. Only half an hour before midnight - still plenty of time, but he felt rushed. He pulled on his trousers and gray homespun shirt, took a small sack with two apples, thinking that he and Lavinia might sit together for a while under the starlight. It would be nice if he recited poetry to her, but Owen didn't know any poems.

He woke with a start and saw by the ticking bedside clock that it was 11:28. Only half an hour before midnight - still plenty of time, but he felt rushed. He pulled on his trousers and gray homespun shirt, took a small sack with two apples, thinking that he and Lavinia might sit together for a while under the starlight. It would be nice if he recited poetry to her, but Owen didn't know any poems.

The door creaked as he pushed it open. He slipped outside, closing it quietly behind him so his father would never know anything was amiss. He made his way up the streets, past the dark cottages and their slumbering inhabitants, beyond the cold and silent racks of the Huang beehives that produced more honey than the village could possibly use. The town's angel statue appeared pale and ethereal under the stars. The night was bright as he climbed the path that led through the close rows of apple trees and reached the top of the orchard hill.

Lavinia wasn't there, although he had hoped she might come early. He checked his pocketwatch - ten minutes until midnight. The Watchmaker claimed that punctuality was the surest demonstration of love.

While waiting, Owen looked up at the stars, tracing the constellations that he knew from books, but rarely saw for himself. Barrel Arbor villagers got up with the first light of dawn and spent little time outside late at night pondering star patterns. The study of such things, as well as the phases of the moon, the movements of planets, combinations of elements, and magic, was the province of expert alchemist-priests, not simple country folk. The Watchmaker understood the clockwork universe, and he told his people everything they needed to know.

To Owen, the assortment of bright lights in the sky looked distressingly random, so he decided to pick out his own patterns, drawing lines, connecting dots. Were his proposed constellations any less valid than the ones in official books? How did the stars know which patterns the Watchmaker imposed?

He became so engrossed in his own thoughts that he lost track of time. Still no sign of Lavinia. He glanced at his pocketwatch and saw it was five past midnight. With a sinking heart, he gazed through the shadowed orchard, trying to see the path leading down the hill. He heard no one approaching, no swish of skirts as she hurried toward him. Maybe she had overslept.

By 12:36, she still had not shown up. He feared that something bad had happened to her. Her house might have caught on fire! But he saw no flames down in the village. Maybe her parents had learned of her illicit plan and locked her inside. But how could they have known?

He waited another ten minutes, then ventured down the path calling her name in a heavy whisper, but there was no response. No one else was abroad at night. Could she have taken another path? He hurried back up to the top of the hill.

By 1:15 a.m., Owen knew that she wasn't going to come. She had let him down.

The real reason whispered around his ears, though he didn't want to hear it. Lavinia hadn't come simply because she hadn't. She had been afraid, or simply unwilling, to bend the rules and break her habits. Now that he thought about it, Owen realized she hadn't taken his bold suggestion seriously at all. Warm and content in her own bed, sleeping peacefully, she probably did not believe that he had been serious. A stolen kiss at midnight under the stars - what a silly idea.

You must put all this foolishness behind you.

In another few weeks, he was going to have to put his dreams away on a high shelf. It didn't seem fair. All his life he had followed the rules. He had done what was expected of him rather than what he wanted; every day mapped out, every event scheduled, every part of his existence moving along like a tiny gear in an infinite chain of other tiny gears, each one turning smoothly, but never going anywhere.

In the distance, he heard a clanging sound, that haunting far-off passage bell, and he turned to see the pillar of steam as a caravan of swollen steamliners chugged out of the mountains, drifting down out of the sky to the rails that followed the river in the valley below.

From the printed schedules, he knew that a steamliner rolled past Barrel Arbor at 1:27 a.m. each night, though he had never been awake to see or hear it. He caught his breath.

On impulse, just to prove that he could, Owen ran down from the top of orchard hill toward the valley, not looking for any path through the tall dewy grasses. Clutching his satchel of apples, he ran as fast as he could without tripping. He could go right to the rails and watch the magnificent caravan roll by, so close he could touch it.

Even though Lavinia hadn't joined him, he vowed to do something exciting this night. What if he never had the opportunity again? What if, when he became an adult, even the very ideas died within him? At least he would see a steamliner up close, and that would be something to remember.

The clanging bell and hiss of steam grew louder as he raced to the tracks. Upon landing on the glowing rails, the train transformed into a narrow stampede of mammoths, a long line of heavy cargo boxes and passenger gondolas lit with phosphorescent running lights, balanced by graceful balloon sacks. A geyser of exhaust bubbled out of the lead engine like the breath of a sleeping white dragon. Steel wheels rolled along the metal lines, and the engines huffed.

As Owen reached the tracks, the sound built like excitement and laughter, energy and applause rolled into one. He stared as the steamliner thundered past. It came from mysterious lands he had never seen, rolling across the landscape toward Crown City . . . which he had also never seen.

He stood transfixed, watching several cargo cars, then a dim passenger gondola filled with the silhouetted heads of sleeping passengers, then more cargo cars. He felt the breath of wind as it rolled past, smelled the steam and sparks and hot metal.

He wished Lavinia were there beside him but knew she would never be. She'd never even think of doing this. His father had shown no interest in watching the steamliners either; they were just a part of daily life, like the sunrise and sunset, coming and going on schedule. All is for the best.

Albion was vast, and Barrel Arbor was not. Would he ever see Crown City and the Clockwork Angels? Ever meet the Watchmaker in his tower?Ever sail the Western Sea? Soon he'd have to put away his mother's books, never again look at the pictures. It seemed impossibly sad to him.

As a battered old cargo car came toward him, he saw the shape of a man hanging out of the open door, the silhouette of a head peering out, a waving hand. Owen was startled as the man shouted over the noise of the steamliner, as if he knew Owen was there. "Hold out your hand, and I'll pull you up."

He froze. He could get aboard the steamliner! He could ride the rails into Crown City. He could see the Angels with his own eyes, before it was too late.

"I shouldn't," he yelled back.

"But do you want to?" the man called, hurtling closer.

The car was upon him, and Owen instinctively - impulsively - reached out to grab the man's hand. The stranger was strong and yanked him off the ground. Owen felt his feet lift away from the siding of the steamliner track, and before he knew it, as quickly as a sudden sneeze, he was pulled up and into the cargo car.

"You did it, young man," said the stranger. "I'm proud of you."

Owen looked back with a dazed feeling, watching as his village rolled away in the distance. The stranger gripped his shoulder to keep him steady.

He couldn't believe he had actually done it, even though he didn't yet grasp what he had done. Owen felt the brisk night breeze on his face, as he turned his gaze away from the receding view of Barrel Arbor to look forward, toward Crown City and the future.

"On my way at last," he said.

Afterword:

by Neil Peart

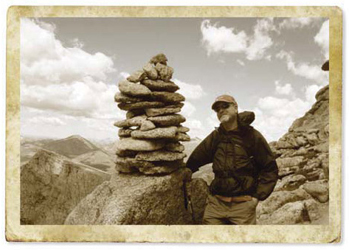

Here is a photograph I took of Kevin on the day he and I began seriously discussing the novelization of Clockwork Angels.

It was August 17, 2010, and the setting was Mount Evans, Colorado. At 14,265 feet, Mount Evans is one of Colorado's "fourteeners" - summits higher than 14,000 feet. Kevin lives in Colorado, and has climbed all fifty-four fourteeners, often with a recorder in his hand - while he hikes, he dictates chapters for upcoming novels. At that time I was on tour with Rush, with a day off between two shows at Red Rocks near Denver, so Kevin invited me to join him on one of the "tamer" fourteeners.

It was August 17, 2010, and the setting was Mount Evans, Colorado. At 14,265 feet, Mount Evans is one of Colorado's "fourteeners" - summits higher than 14,000 feet. Kevin lives in Colorado, and has climbed all fifty-four fourteeners, often with a recorder in his hand - while he hikes, he dictates chapters for upcoming novels. At that time I was on tour with Rush, with a day off between two shows at Red Rocks near Denver, so Kevin invited me to join him on one of the "tamer" fourteeners.

For something like twenty years, Kevin and I had discussed working on a project together that would marry music, lyrics, and prose fiction. The right idea and timing eluded us for a long time, but at last, both converged perfectly. It is as though that occasion had to wait until both of us were truly ready, as mature artists and - perhaps - as mature human beings, too.

I had started working on the lyrics in late 2009, and in early 2010 the band recorded the first two songs for the album, "Caravan" and "BU2B." Several of the others were written by then, and I had the lyrics fairly well mapped out. I described to Kevin the basic skeleton of the plot and characters, and he had many wonderful ideas for expanding both. Kevin has unparalleled world-building and story-building skills, and he brought both fully to bear on this project. We started "framing" this alternate world, building its foundation, its infrastructure. We had to reinforce and develop my sketchy ideas on how alchemy might fit into the steampunk scenario - "the future as seen from the past," from, say, the late nineteenth century, as imagined by Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. What came to be known as the steampunk genre was partly pioneered by Kevin in his early fantasy writings - when, as he says, "We didn't know there was a 'thing' to be part of."

Steampunk is also sometimes described as "the future as it ought to have been," for it often portrays a romantic and even utopian "alternative future." I wanted that quality in this world - for it not to be a dystopia - and I believe that despite the Watchmaker's oppressive rule, Albion is rather a nice place. And who wouldn't want to visit Crown City and see the Clockwork Angels? (And breathe that heady colored smoke?)

On the story-building side, right away Kevin recognized the basic symbolic themes of the Watchmaker and the Anarchist - extreme order versus extreme freedom - which I had not consciously noted. Together we developed their characters and interactions, bridging my necessarily "brisk" plot points in the songs with connective tissue and richer details. Over the next eighteen months, we continued to share ideas and suggestions - sometimes many times a day, and each of our "flights" would spark the other.

As my thirty-eight years with Rush will attest, I very much enjoy collaboration with like-minded artists. Working up this story with Kevin was one of the easiest, yet most satisfying projects I have ever shared - easiest, because we almost always simply agreed with each other's additions to the story, and most satisfying because I am so proud of the result.

The same applies to the contributions by Hugh Syme, whose art has glorified every piece of work bearing the band's name, or my name, since 1975. From the very conception of the Clockwork Angels story, Hugh shared the "vision," and between us we developed the wonderful illustrations he created, and which enrich this story so much. As always, if I could imagine it, he could picture it.

Voltaire's Candide (1759) was an early model for the story arc: a philosophical satire about a naïve, optimistic youth whose upbringing ("I was brought up to believe") does not prepare him for the harrowing adventures that bring him to grief, disillusionment, and despair. Finally, Candide finds peace and wisdom on a farm near Constantinople, working in his garden.

First reading Candide in my twenties, I was amazed to discover that Voltaire was a philosopher with a sense of humor - the only one I know of even now, apart from Nietzsche (occasionally). Right from the beginning of Candide, the tale is woven with a needle of irony dipped in acid - sometimes only just keeping its clever head above sarcasm - and within a couple of pages you encounter a laugh-out-loud farcical scene being observed, where the "sage Dr. Pangloss" is in the woods, "giving a lecture in experimental philosophy" to a chambermaid, "a little brown wench, very pretty and very tractable."

Voltaire's story about Candide was delivered with a lighthearted, impish wit that, three centuries later, would inform John Barth's picaresque play on the story, The Sot-Weed Factor - another little influence on the plot for Clockwork Angels.

The character of the Anarchist, perhaps a classic "screen villain," was partly inspired by Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent, and by a character in Michael Ondaatje's In the Skin of a Lion - wo very different takes on anarchists, who can be either idealists who believe that humans don't need leaders, or brutish, murderous sociopaths. (Obviously those polarities resonate in our own timeline.) The carnival setting is drawn from Robertson Davies's World of Wonders and the fine Beat-era novel by Herbert Gold, The Man Who Was Not With It.

The fascinating history of Spanish exploration in what is now the American Southwest was largely driven by an enduring legend of the Seven Cities of Gold. The setting was irresistible to me, and to Kevin, because we have both traveled widely, on wheels and on foot, in the Western deserts of Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and California. (Though I was not dictating books along the way.) Echoes are plain in the arches and other redrock formations of Southern Utah, the "Island in the Sky" in Canyonlands National Park, Acoma "Sky City" and the abandoned pueblos in New Mexico.

In contrast, the idea for the Wreckers came from another "Far West" - Cornwall, in England - drawn from some of Daphne du Maurier's stories of that region, both fictional and historical. Years ago I read Jamaica Inn and others set in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in that part of the world, and was appalled to think that people not only plundered wrecked ships without a care for rescuing survivors, but were so cold-blooded as to lure them to their dooms with false lights.

Two songs that were late additions to the album, "Halo Effect" and "Headlong Flight," had their own stories. During our hike up Mount Evans, Kevin and I also talked about our own youths, and the kind of naïve illusions that had colored our histories. That became "Halo Effect." In late 2011, my longtime friend and drum teacher, Freddie Gruber, passed away at age eighty-four. Near the end, he would rally briefly and entertain his friends and students gathered around with tales from his adventurous life - Manhattan in the forties, Vegas in the fifties, Los Angeles in the sixties and seventies and up to that day.Then he would shake his head and say, "I had quite a ride. I wish I could do it all again."

I felt inspired to echo that lament in the song "Headlong Flight" - although I had never felt that way myself. To the contrary, as much as I appreciate and enjoy my life now, I remain glad I don't have to do it all again.

That dichotomy is reflected in the ending of Candide. Dr. Pangloss continues to hold forth with his Spinoza-based "all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds," which Voltaire has been gleefully skewering throughout the novel. (I felt the same about Schopenhauer's evil pronouncement that informs what Owen Hardy was "brought up to believe": "Whatever happens to us must be what we deserve, for it could not happen if we did not deserve it." Outrageous! )

In the final scene of Candide, the title character displays his impatience with philosophy and reveals the pragmatic wisdom he has attained. "Pangloss sometimes would say to Candide, 'All events are linked together in the best of all possible worlds; for, after all, had you not been kicked out of a magnificent castle for love of Miss Cunégonde, had you not been put into the Inquisition, had you not traveled across America on foot, had you not stabbed the Baron with your sword, had you not lost all your sheep from the fine country of El Dorado, then you wouldn't be here eating preserved citrons and pistachio nuts.'

'Excellently observed,' answered Candide; 'but we must cultivate our garden.'"

Kevin and I had great fun coming up with names for the places and characters. Watchmaking components gave us Barrel Arbor, the Winding Pinion River, Crown City and its circular boulevards (Crown Wheel, Balance Wheel, and Center Wheel), and the Regulators. Albion is an ancient name for England, while Poseidon was the legendary capital of Atlantis. Cíbola was one of the Spanish names for the Seven Cities.

In 1527, a Spanish expedition of 600 men set out from present-day Florida to occupy the New World. In a land without maps, they were immediately lost, and the force was steadily depleted by starvation, thirst, disease, exposure, a hurricane, and being enslaved by the natives (ironic foreshadowing). The expedition's treasurer was Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (meaning "cow's head," it actually was a noble entitlement, not an insult), and he ended up as the leader of only four survivors who made it to Mexico City, after many harrowing adventures. Another unlikely survivor was an African slave, Esteban, and he and Cabeza de Vaca were the first to spread tales of the Seven Cities of Gold. Their stories would lure many another adventurer.

The Anarchist's stage name among the carnies, "D'Angelo Misterioso," was modeled after a bit of rock trivia: George Harrison's contractually necessary pseudonym on the Cream song "Badge," which he co-wrote and played guitar on, was "L'Angelo Misterioso."

At first Kevin and I were building the story around a character referred to only as "Our Hero," but we needed a real name - so I suggested we use those initials: Owen Hardy. (Owen from one of my daughter Olivia's picture books, and Hardy because the village of Barrel Arbor has a Thomas Hardy air of bucolic quaintness.)

Kevin wanted Owen's first love to have a kind of "vanilla" flavor, so I suggested the near anagram of Lavinia. With the omnipotence of the world-builder, I was determined to make this society entirely mixed in racial characteristics, from skin colors to names, so together Kevin and I made her family the Paquettes (a fallen woman in Candide is named Pacquette), and introduced Oliveira, Huang, Tomio, Francesca, Guerrero (Spanish for "warrior"), and so on. Owen's mother is named Hanneke Lakota, which, like his brown skin, suggests that he might have Native American blood.

Kevin also had fun weaving in many references to Rush lyrics, and though they will not disrupt the reading experience for those who don't get them, they may entertain those who do. (Perhaps one day we'll have a contest to see how many of them people can find.)

All of those details built up over several drafts, with special attention brought to specific scenes in between. And still notes were exchanged in rapid-fire volleys. Kevin writes extraordinarily fast, often working on a few projects at the same time, but he is able to bring complete focus to any story because while he writes it, he lives it. Sometimes, while he was hiding away in a cabin in the Colorado mountains and working on the story, he would end a note with something like, "Now I have to go do terrible things to Owen in Poseidon City."

In mid-May 2012, Kevin sent me what we considered to be the final draft of Clockwork Angels: The Novel. I had the typescript printed and bound, and took it with me to a cabin among the redwoods in Big Sur. Sunlight filtered down through the big trees, Steller's jays visited my porch railing, the Big Sur River murmured in its rocky bed, and woodsmoke from the neighboring campground perfumed the air.

What a delight it was to read our story that way, freshly immersed in it after several somewhat scattershot previous readings, and truly feeling it - Anton Hardy's sorrow over his lost wife, and Owen's attempts to find his way - find himself - through the tribulations that mold him into a strong and righteous man. In response to suggestions from his sharp-eyed editor (and wife) Rebecca Moesta, a few trusted "test readers," and myself, Kevin had added many little touches of detail and humor - like the antics of the three clowns imitating their fellow carnies. (No prizes for guessing who those three characters are modeled after!) He also further developed some of his marvelous "inventions," like the clockwork Orrery, the "Imaginarium," and the Destiny Calculator, that I already considered astonishing, while weaving additional splendid details into scenes like the performance of the Clockwork Angels.

After finishing that final read, and pouring myself a celebratory beverage to toast the big trees, the jays, the river, and the book, I wrote to Kevin:

"Bleary-eyed, but triumphant, I have just finished a pleasurable day of lying around my cabin in the redwoods and reading the book. Though I had been facing the task as something of a 'duty,' it turned out to be a very pleasurable experience."

After a bit of "technical talk" about various details and improvements, I concluded:

"The entire end section, from the Wreckers out, felt like an emotional climax, not just a dramatic one.

"I am so glad we made this happen."

Puchase

Clockwork Angels: The Novel at Amazon.Com