|

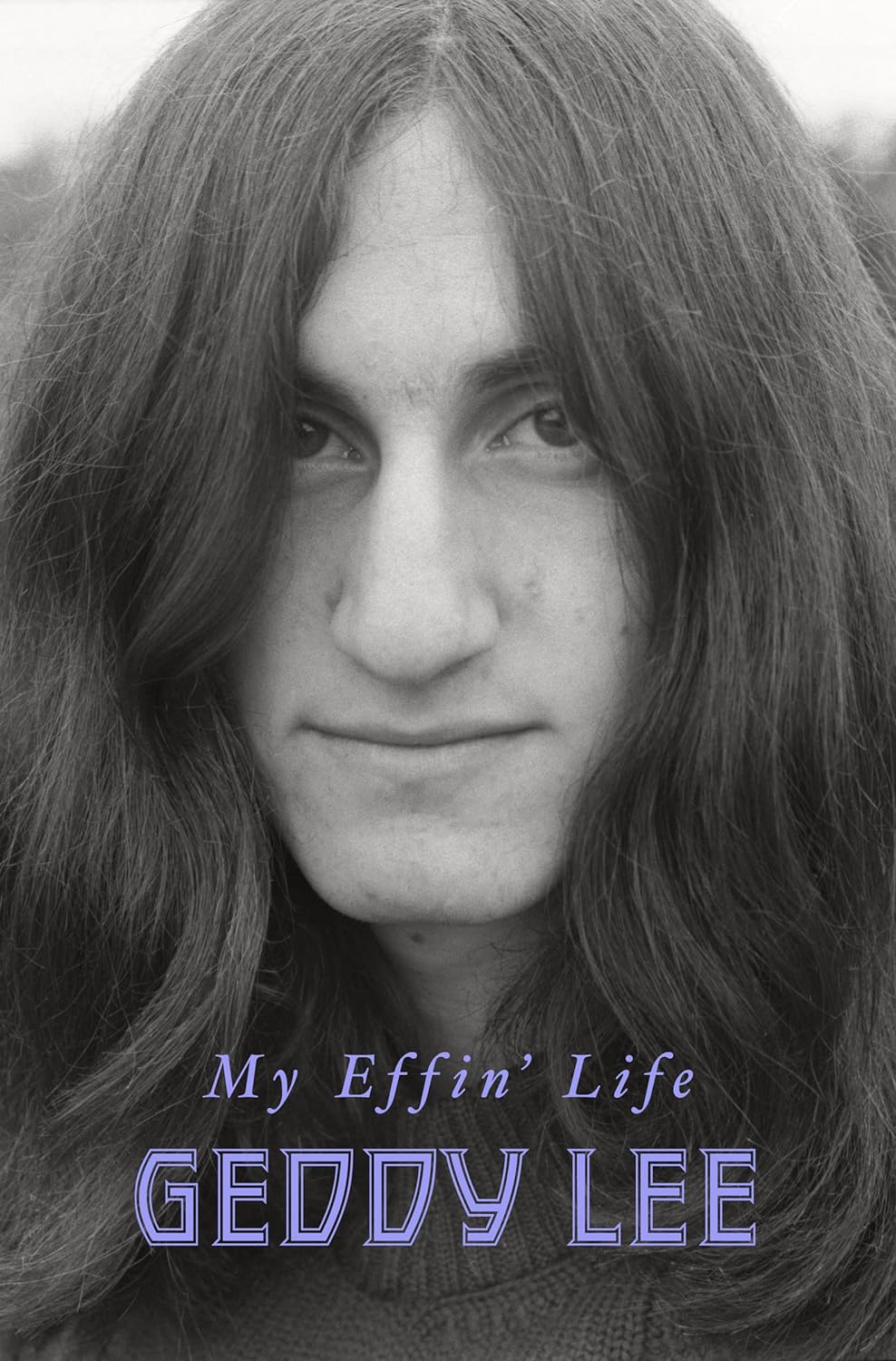

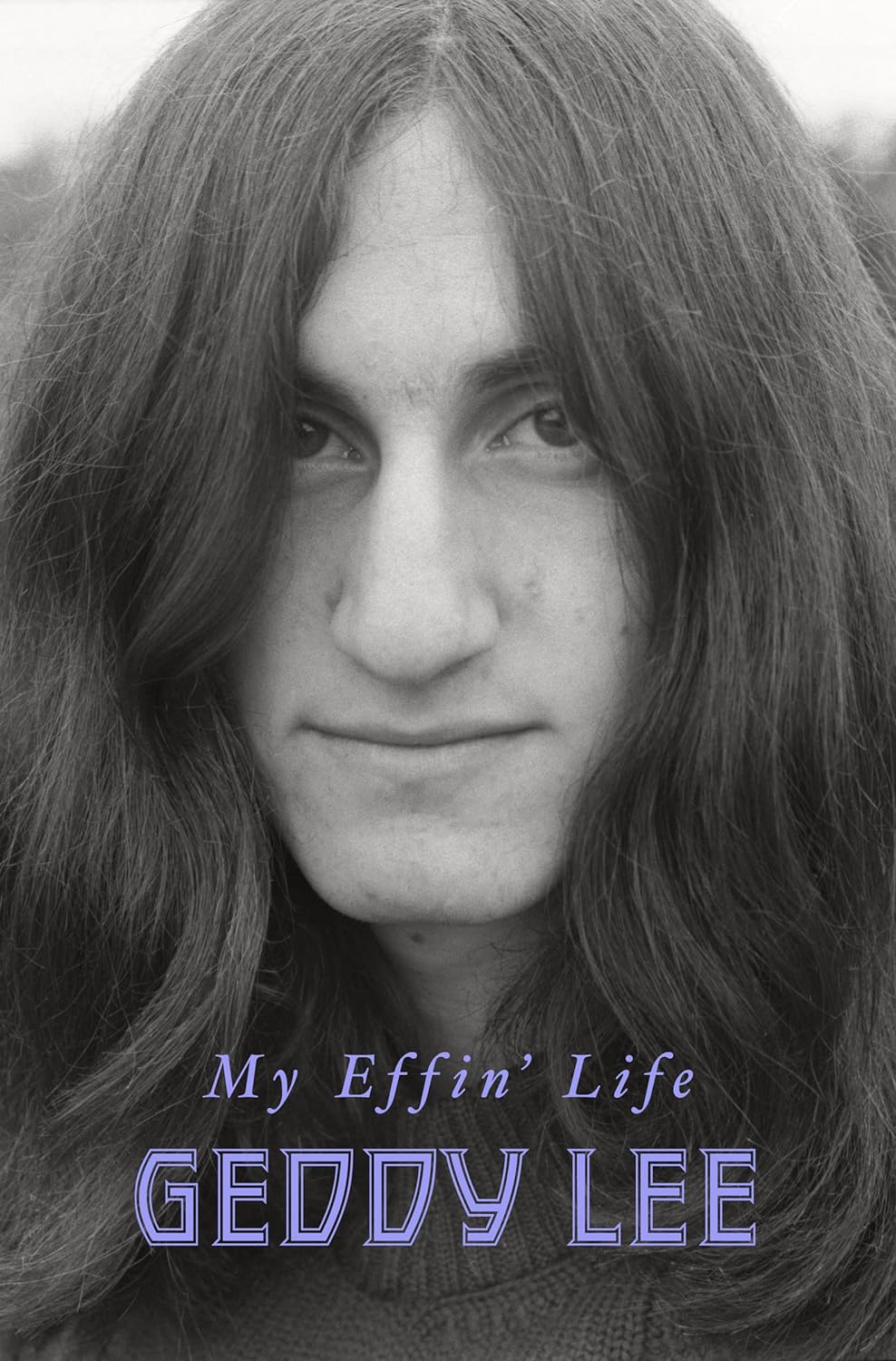

GEDDY LEE November 14th, 2023 with Daniel Richler |

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapters 7-28

Acknowledgments

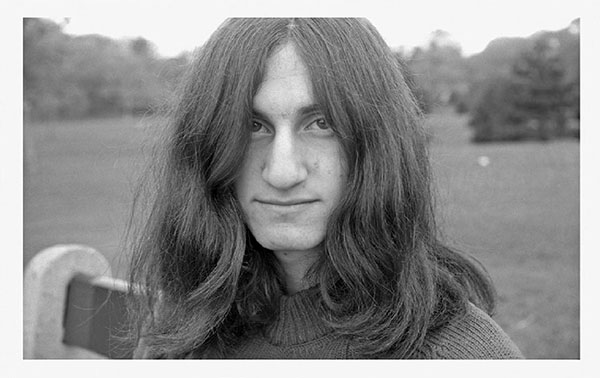

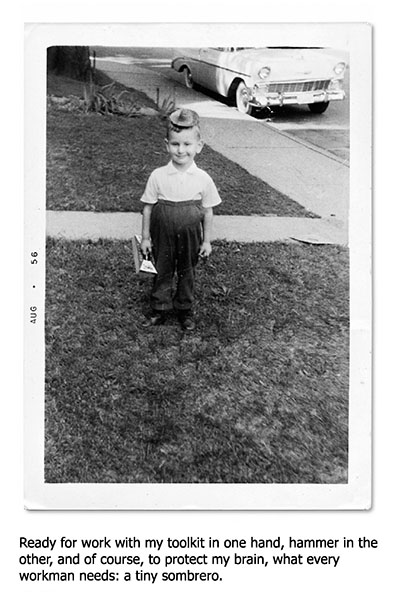

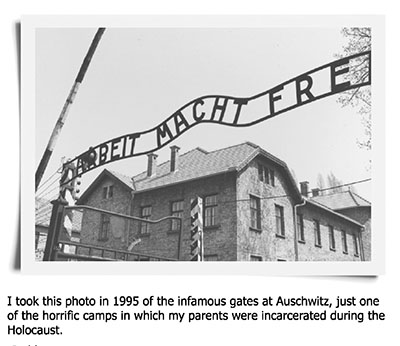

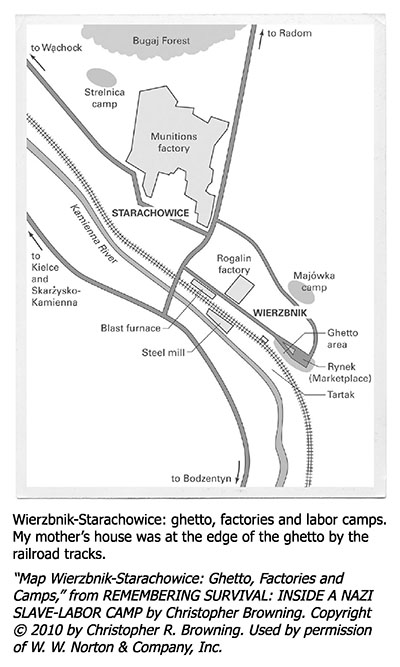

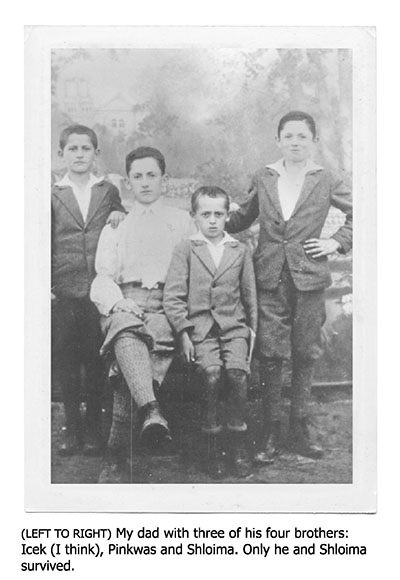

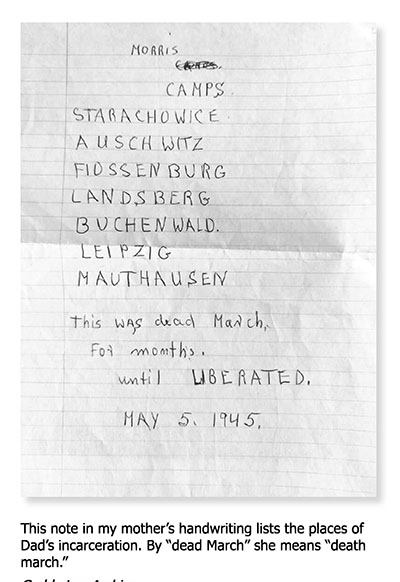

Photo Section

About the Authorv Also by Geddy Lee

-Neil Peart

As a comic in all seriousness

-Eugene Levy, as Bobby Bittman

You probably know me as Geddy Lee, but my birthname was

Gershon Eliezer Weinrib, after my maternal grandfather who was

murdered in the Holocaust. As per tradition, my mom, her sister and

her brother all named their first-born male children in his honour;

my two cousins and I, all of us born within a couple of years of one

another, were given that same first name, Gershon.

In the old country my family spoke both Yiddish and Polish, the

former being the language they used at home and whenever they

didn’t want the Poles to understand what they were saying. So my

family all had both Yiddish and Polish names, too. Mom, for

example, was known as both Manya and Malka. On most of the

official documents I’ve found, their Yiddish names were used but

sometimes spelled unrecognizably, as they would have been

pronounced by some bureaucrat in the Polish or German

government - or, after the Second World War, the International

Refugee Organization.

As was the case with my grandfather, whom I've seen referred to

as Gershon, Gierszon, Garshon and Garszon, identification for the

emigres was never a simple matter. My father’s name, for example,

had its own set of complications. His full Yiddish name was Moshe

Meir ben Aharon Ha Levi, yet in an old passport that I recently

discovered, it’s spelled out as Moszek Wajnryb and its anglicized

translation, Morris Weinrib. I’d never even heard the name Moszek

before; my mom and our family usually called him Monyek, Moishe

or simply Morris.

After eleven days at sea, on December 20, 1948, the ship carrying my parents from Germany docked in Halifax, Canada. They

barely spoke any English as they walked down that ramp, so when

they registered with customs and immigration, the official came up

with anglicized approximations of their names, beginning with the

same first letter. Thus Manya became “Mary” and Moishe became

“Morris,” and in turn when their children were born, they gave us

each a Jewish name and its English equivalent: in my case, Gershon

and “Gary.”

After eleven days at sea, on December 20, 1948, the ship carrying my parents from Germany docked in Halifax, Canada. They

barely spoke any English as they walked down that ramp, so when

they registered with customs and immigration, the official came up

with anglicized approximations of their names, beginning with the

same first letter. Thus Manya became “Mary” and Moishe became

“Morris,” and in turn when their children were born, they gave us

each a Jewish name and its English equivalent: in my case, Gershon

and “Gary.”

My middle name is Eliezer, but from kindergarten through the end

of public school, I answered at roll call to “Gary Lorne Weinrib.”

Confused? I was too! When I turned sixteen and was preparing to

apply for a driver's licence and a Canadian Federation of Musicians

card, I asked my mother for a copy of my birth certificate, which she

duly requested from the government. When it arrived, I opened the

envelope and found myself listed as Gary Lee Weinrib. WTF?

“Mom,” I said, “what’s going on here? It says my middle name is

Lee, not Lorne!”

She looked away, thought about it for a moment and said with a

sheepish laugh, “Oy, takeh. Yah. I tink maybe you vere Lee... Your

cousin, Me was Lorne. I forgot....”

Huh? You forgot? I’m not sure which freaked me out more: my

sudden loss of identity or the fact that my own mother couldn't

remember my effin’ name.

I recently discovered that my cousin Gary Rubinstein was in fact

the actual recipient of the middle name Lorne. The best explanation

I have for the mix-up is that, since Mom would have been speaking

English for only a few years by the time I was born, the anglicized

take on Eliezer was for her just an afterthought. And after she and

her siblings made a group decision to name all their first-born male

children after my grandfather, she misremembered which middle

name they'd agreed on for me.

But wait... There’s more.

My mom usually called me Garshon at home, saving Gary for

when we were out in public. Then one day in my early teens, I was

hanging out in front of our house with my pal Burd when she called

me indoors for supper.

“Hey,” Burd said. “If your name is Gary, how come your mom

calls you Geddy?”

“She doesn't,” I said. “Her accent only makes it sound like that.”

He laughed and said, “Well, I’m gonna start callin’ you Geddy

too!” And that was that.

When I turned pro, the musicians’ union application form asked

for “professional, stage or band name” and I thought, How cool.

Perhaps I should be ashamed of this, but in my desperation to

assimilate into a less ethnic world, I didn’t think “Weinrib” sounded

very rock and roll. Lennon, Plant, Clapton, Moon and Hendrix-now,

those were effin’ rock star names. (In an attempt at self-justification,

I asked myself if Robert Allen Zimmerman had had similar fears

before he became Bob Dylan.) So I combined my nickname and

rediscovered middle name to create a professional moniker for

myself and legitimize my new aspiring identity.

A few years later I took that even further and changed my first

name legally to Geddy. By then, even my siblings were calling me

Geddy or Ged, so it was all good. To people who asked, I’d explain

that it was like in Leave It to Beaver, where the kid's real name was

Theodore but everyone, even his parents, called him “The Beaver.”

At any rate, as you can see, I had two identities right from birth:

“Gershon Eliezer” and “Gary Lorne.”

And now “Geddy Lee” made three...

You may naturally assume that I grew up in a house rich in music,

that my desire to play must have grown out of musical influences all

around me. But music was in little evidence in my childhood home.

The radio was always on in the car, but I don’t recall Dad ever speaking about music, or mentioning any artists he liked, or even

humming along as we drove. I just thought music didn’t register

with him.

It wasn’t until many years after his death, when I was playing a

show in Detroit and reconnected with the family of his only surviving

brother, Sam, living in the suburbs of the Motor City, that my aunt

Charlotte let slip some startling information.

“It's so nice zat you have become a musician,” she said casually.

“After all, so was your father” As my brain reeled, she continued,

“Oh, yes, back in za old country, he played za balalaika, I zink.

Parties, bar mitzvahs, weddings and so on.”

All I could muster was a “Really?” It seemed so out of character

with the man I thought I’d known that I wasn’t ready to believe

what she was saying. Was he really a “player”? If so, music must

have thrilled him in his early life and . . . oh man, what questions I

would have loved to ask him. But foremost in my mind was why my

mother had never mentioned it. Seeing as I was a professional

musician by that time, you’d think it would have been a pretty vital

tidbit to share with me, no? I was more perplexed than angry, and

immediately after getting home from that leg of the tour I asked her

to verify the story and give me an explanation.

Visibly embarrassed, she proceeded to relay this to me... Fora

while after their liberation my parents lived in Germany at the

Displaced Persons camp at Bergen-Belsen, formerly the officers’

quarters of the concentration camp where my mom, her mother and

her sister had been incarcerated for the final months of the Second

World War. (Obviously this is a much bigger story, and one that I will

be telling you.) They then moved into an apartment in a nearby

town, trying to put their lives back together as so many survivors

were, and finally committed to emigrating to Canada. As they were

readying for departure, my dad declared that he was packing his

balalaika, but my mom refused to allow him to “schlep dat feedef’

across the ocean with them. She regarded the instrument as

superfluous, his musical endeavours an indulgence they could ill

afford as they forged a new life in a new land. This, she now told

me, was a decision she’d long regretted. It was a heartfelt and meaningful confession, and for me a revelation as to my own

inherent musical aptitude. I guess I came by it honestly! It’s in my

effin’ genes! Yet, sadly, it also goes a long way to explain my father’s

silence on all things musical and so many other joys of life. Looking

back all those years later, I had to wonder if I’d missed any signs of

his musical soul. Perhaps the decision to buy a piano so my sister,

Susie, could take lessons was his way of planting a musical seed

and, as such, connecting with his buried past. But I will never know.

I was six or so when my parents bought that piano-primarily for

Susie, who was two years older than me. Apparently, they thought

this was what well-raised Canadian schoolchildren did. A piano

teacher was hired, and as Susie did battle with the keyboard, I'd

quietly listen to the lesson from the next room or hiding under the

table. She came to play well enough to participate in a school recital

but didn’t stick with it. After I’d enjoyed some success in music, by

contrast, my mom liked to relate how, once the teacher had left, I

would hop on the piano stool and, by ear, pick out the melodies

Susie had been learning- "prefectly,” as she insisted. Like any big

fish tale, this story was most definitely enhanced over time. I do

recall tinkling the ivories after Susie’s lessons, but I can assure you I

was no Glenn Gould.

In the earliest memory I have of my father, the three-year-old me is

at the picture window of our Shaw Street home in downtown

Toronto, waiting for him to return from work. The winter light of day

is fading into dusk - always a melancholy time for me, even now -

and I can hear the tinny fanfare of The Mickey Mouse Club on

television in the background. I watch him coming down our street

from the streetcar stop at the corner, up the walkway and into the house with a tight smile and a weary Ich bin shoyn aheym‘I’m

home, already!” He brushes by me on his way to the kitchen, goes

straight to a high-up cupboard and takes out a bottle of Canadian

Club rye whiskey. He pours himself a snort, knocks it back, then

smacks his lips and makes a sound I always remember with a smile

of my own, “Ahh...” It was only after he’d had his schnapps that

he felt rid of the day’s grime and could pick me up and give me a

kiss, playfully scratching my face with his five o’clock stubble. (I can

smell the liquor on his breath as I type these words.) Then he puts

me down and goes on to do the same to Susie, and finally hugs and

kisses Our mom.

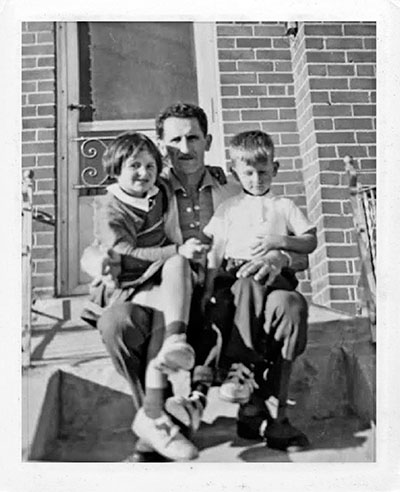

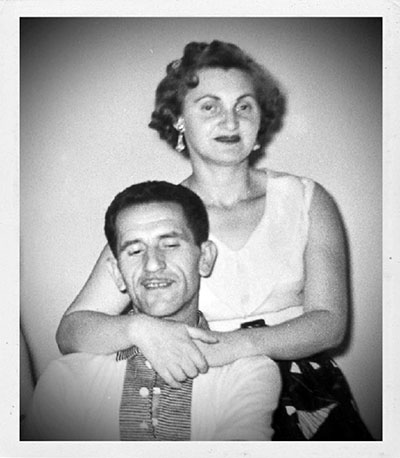

This handsome man with dark European looks came to Canada in

1948 with the proverbial ten dollars in his pocket and the love of his

life on his arm. Moishe and Manya stepped foot on their new

homeland as Morris and Mary - anglicized personae for an anglicized

world - seeking a fresh start in a dominion unscarred by war and

genocide. Morris already had family here: a sister, Rose (Ruchla),

who had left Poland for Toronto before the war. For someone who

had lost both of his parents, five siblings and countless other family

members, all murdered by the Nazis, reuniting with her was the

urgent and natural thing to do. Soon after their arrival, the

remainder of my mother’s family chose to join her and Morris in their

great Canadian adventure: her sister, Ida; brother, Harold; and their

spouses, but most important, her mother, another Rose and the

heroine of the Rubinstein tribe, as I will show you in time.

My dad was a loving father, but strict. He had an explosive

temper, but it took a lot to trigger it. I pause here, because it seems

unfair to mention any of the few bad moments in my short life with

him; unfair because the fact that he survived the war, the fact that

he made it to the blessed shores of Canada at all, is a miracle.

Suffice it to say that I was pretty accomplished at provoking him,

and as with most parents of his generation, if any of us kids did

something really wrong, well, we'd get an ass-whooping.

We knew that he and Mom cared deeply for each other. They

argued sometimes, but hey, that was life in a Jewish home. What

seems like shouting to gentiles (or “white people,” as we sometimes referred to them) was just a regular conversation around our dinner

table. When the whole family got together for the High Holidays...

my god, it was a shouting match! But the love my parents had for

each other won out over any argument, and they were

demonstrative about it. I remember when I was about eight years

old, Dad must have been feeling amorous. We were watching TV

when he surreptitiously raised his arms above his head to get my

mom’s attention and made a scratching motion with one hand in the

opposite palm. I didn’t know what that meant until the kids at school

told me it was a signal for sex. Wow, really? Ew!

Both our parents worked hard. Motivated to build a new life and

raise a family, they held down factory jobs on Spadina Avenue, the

hub of Toronto's shmatte industry, which, like many greenhorns

when they first landed, they referred to simply as “on Spadina.” Once my mom had Susie, and me two years later, she stopped work

and it was up to my dad to hustle a living and pay the bills. It helped

that they also received reparations from the German government,

but we were a decidedly working-class family without much spare

cash or time for the pursuit of frivolous hobbies like music. With no

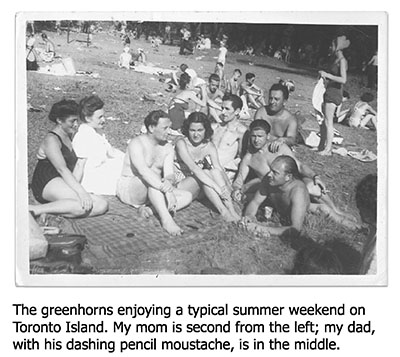

money for hotels or fancy holidays, we did like many immigrants still

do in Toronto: on Sundays we picnicked with my family and cousins

on Toronto Island or in High Park. The men would sit on a blanket

playing cards and laughing, and I always could hear my dad's voice

louder than the others’; They drank Red Cap Ale and Carling Black

Label; if you’re a Canadian, you'll remember those stubby little

bottles. (I remember sneaking away once to taste a Black Label, but

to me at that age it was just god-awful.)

Both our parents worked hard. Motivated to build a new life and

raise a family, they held down factory jobs on Spadina Avenue, the

hub of Toronto's shmatte industry, which, like many greenhorns

when they first landed, they referred to simply as “on Spadina.” Once my mom had Susie, and me two years later, she stopped work

and it was up to my dad to hustle a living and pay the bills. It helped

that they also received reparations from the German government,

but we were a decidedly working-class family without much spare

cash or time for the pursuit of frivolous hobbies like music. With no

money for hotels or fancy holidays, we did like many immigrants still

do in Toronto: on Sundays we picnicked with my family and cousins

on Toronto Island or in High Park. The men would sit on a blanket

playing cards and laughing, and I always could hear my dad's voice

louder than the others’; They drank Red Cap Ale and Carling Black

Label; if you’re a Canadian, you'll remember those stubby little

bottles. (I remember sneaking away once to taste a Black Label, but

to me at that age it was just god-awful.)

At one point Dad was hired by a distant cousin to work in his

“shoddy mill." He rose in the ranks to a position of some authority,

but one day came home ranting that he’d been unfairly treated by

his own cousin and in a rage had quit his job. It didn’t take him long

to bounce back, though. He found a partner and proudly started a

business of his own, Lakeview Felt. I remember going there with him

and wandering around the wide-boarded floors in awe of the

machines and the odors of wool and oil. But that, too, came crashing

down when, at the first sign of struggle, the partner panicked and

made a quick deal behind his back with his former boss. After that

betrayal Dad was unemployed for a lengthy period. I remember him

being around the house and down in the dumps while he looked for

Opportunities. Then he decided he no longer wanted to worry about

partners or factory life at all and started looking for a small retail

business instead. He eventually found a little variety store called

Times Square Discount in the burgeoning town of Newmarket,

Ontario. That was a pretty bold move on his part, since he’d never

worked in retail before, but he ran it well, the locals liked him a lot

and there was even an article in the local newspaper reporting on

him as a boon to the community.

After the war and throughout my childhood, Toronto’s immigrant

population was bent on moving north. My mother used to say the

Jews were the first, and when they went even farther out the Italians would move in and so on, like hand-me-down

neighbourhoods. It was an exodus from Toronto’s crowded, grimy

downtown, where they had little choice but to live and work when

they’d first arrived. The charm of a home with older bones was lost

on them. This was the New World, after all; they wanted a New

World house with a new kitchen, a two-car garage with a backyard

and space between the houses on either side, as different as they

could get from the crowded, battered buildings they'd left behind in

Europe. Our first house had been a rental on Crawford Street, in

what’s now known as Little Portugal, which is where my sister, Susie,

was born; when I came along we moved to another, one block over,

on Shaw Street. By the time I was five they had scraped enough

money together to actually buy a house, and that investment took

them north to 53 Vinci Crescent, a small bungalow in the North

Toronto suburb of Downsview.

Situated on the crescent, we were blessed with a large triangular

slice of property and a rare bower of plum and apple and cherry

trees in the backyard, a blissful Garden of Eden that transcended our

humdrum location. I’d play there with my friends and, towards the

end of summer, pick off the ripest fruit. The blackberries were pretty

sweet, though the plums were never as ready to pluck as my

parents insisted they were. Maybe it was wishful thinking on their part, but most likely they were relishing the fact that, after all they

had survived during the war, here they were now in their own home,

growing their own fruit, which, ripe or not, tasted of ... well,

freedom. And to this day I, too, have a taste for plums that are a

little hard and tart.

Situated on the crescent, we were blessed with a large triangular

slice of property and a rare bower of plum and apple and cherry

trees in the backyard, a blissful Garden of Eden that transcended our

humdrum location. I’d play there with my friends and, towards the

end of summer, pick off the ripest fruit. The blackberries were pretty

sweet, though the plums were never as ready to pluck as my

parents insisted they were. Maybe it was wishful thinking on their part, but most likely they were relishing the fact that, after all they

had survived during the war, here they were now in their own home,

growing their own fruit, which, ripe or not, tasted of ... well,

freedom. And to this day I, too, have a taste for plums that are a

little hard and tart.

Fruit trees aside, what were these suburbs like? In a word, bland. In

two words: mind-numbingly bland. The architecture was

unimaginative and repetitive, practically but not aesthetically built,

with garages jutting out in front of the houses - the inescapable

message being that cars were more important than the people who

lived there. The neighbourhoods were virtually treeless, the

backyards big but mostly empty except for the occasional swing set,

with metal or wooden fences so low you could stick your nose into

your neighbours’ business. Ironically, many years later when my son,

Julian, was the same age and we’d take him to the suburbs to visit

my mom, he never wanted to leave. He’d ask, “How come we can't

live in the suburbs like Bubbe does? It’s so clean and beautiful.”

Yikes! One child's ceiling is another one’s floor, I guess.

To my parents, of course, the burbs must have seemed like

heaven, a safe place where their kids were free to play in the streets

or ride off on their bikes pretty much anywhere, but the reality was

that having survived the war, they had other things on their mind,

like building a new life. Today every minute of a child’s day is

monitored, but in those days there was neither the time nor the

inclination for helicoptering. As children themselves under

bombardment, they’d have routinely been sent on hazardous

missions such as dashing out for loaves of bread; now they’d look up

from their work benches only if they heard we’d gotten into serious

trouble - and they didn’t know the half of what we got up to. I

remember one time we rode our bikes over to my new school, when

we saw some older boys climbing up a drainpipe to retrieve a load of

tennis balls that other kids had lost up there. We climbed up after

them - or at least I did, for when I looked around, I realized my pals had decided against it and split. I scrambled about the rooftop and

collected as many balls as I could while they shimmied back down.

Only then did I fully realize how high up I was, how much scarier it

would be to descend than it had been to climb. I tried to slide down

a drainpipe but slipped and landed flat on my back with the wind

knocked right out of me, gasping up at the vast blue dome of

suburban sky. I eventually limped home with my bike and my swag,

snuck past my mom, who was preparing dinner, and got into the tub

to soak my aching body. I was sore for days. Did anyone notice?

Nope, but hey, that was a kid's life back then.

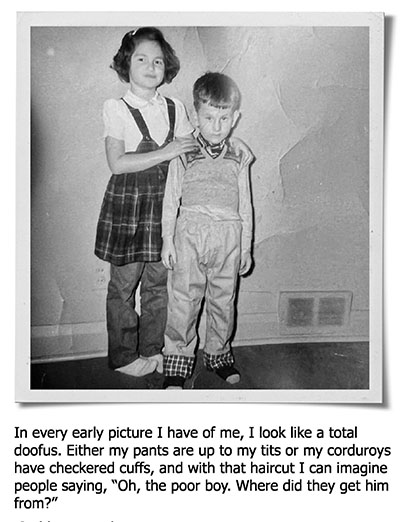

At Faywood Public School I was something of a loner, a quiet kid

who rarely got into trouble. I did my schoolwork in my _ usual

unnoticeable and less-than-stellar manner, with no particular passion

for any particular subject. My report cards consistently featured

comments to the effect of “If he would only apply himself, he could

do very well,” or “Gary has a tendency to daydream in class.” I

remember thinking, What does "apply himself” even mean? I was a

classic underachiever, neither bad enough to fail nor good enough to

excel. It's a common mistake to assume that when a kid (or an adult

for that matter) is quiet, he must be some sort of deep thinker. In

my case I’m afraid it was simply that I didn’t have much to say. Not

all still waters run deep.

In grade five, I sang in the school choir-that was one thing I can

say I really did enjoy. (It will come as no surprise to you that I was a

soprano.) I attended practices for the Leonard Bernstein musical On

the Town as an alternate, meaning I’d only get to perform if

someone fell ill. The night of the play, I was sort of dopily wandering

around the school looking for where the alternates got to hang out

and must have looked lost. A teacher I had previously seen in the

schoolyard and pegged for someone pretty mean came up to me

and asked what I was up to. I shrugged kinda pathetically. He said,

“Follow me!” and took me up to a little room where the spotlights

were operated. “How would you like to help out?” he said, and for

the two-night run I swung those big scorching Klieg lights to and fro

across the stage. It was total magic up there, way more fun than

singing in the choir. To see the production from that perspective was surreal, and I loved being part of the crew. My first taste of show

business, thanks to a kind man who made me feel useful and

valued. Thank you, Mr. Geggie.

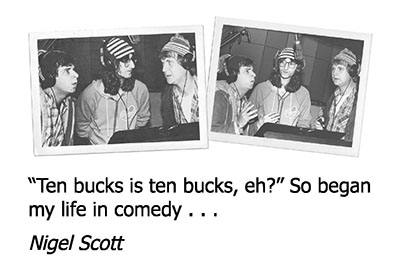

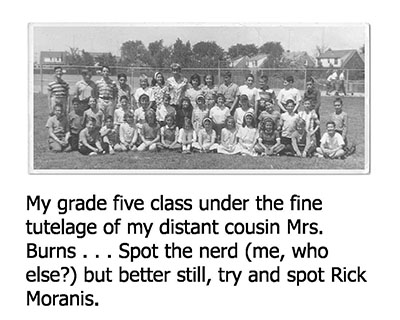

Oh, before I continue, here’s a piece of trivia from my public

school days: there was a boy in my class named Rick Moranis. Yes,

the Rick Moranis of Ghostbusters and Little Shop of Horrors fame.

We weren't close friends or anything but were in the same class

every year from kindergarten right through to grade six. In 1981, by

which time he’d become successful as one of the McKenzie Brothers

in the “Great White North” sketches on SCTV, he asked me to sing

the lead on a song called “Take Off!” for their comedy album, The

Great White North. That would be my first entry into the Top 20 and

the biggest hit single of my career!

Around grade four or five, nerd that I was, I started collecting

stamps. My starter collection was a beat-up old album my father

gave me. For years, I was under the impression that it had been his

own, but I don’t remember him ever showing any interest in

philately, and knowing what I know now about his life in the

aftermath of the war in Europe, I suspect that he either acquired it

on the black market there or, most likely, it had been given to him in

Canada and he passed it on to me. Anyway, there was a kid in my

class I’d go to hobby shops with, whenever I could afford it, to buy

stamps from far-off countries. While Canadian stamps looked dull to

me, featuring nothing but variations on Queen Elizabeth's profile, I

was transported by colourful designs from mysterious and exotic

sources like “Republique du Togo” and “Magyar Posta.” I embraced

stamps as a way of seeing the world from my bedroom (or my desk

during exceptionally boring math classes), and considering my

obsessive, almost addictive nature, I think of them now as a

gateway drug of sorts. Those stamps were, you could say, my first

art collection.

Just before I started grade six in the spring of 1964, Mom and Dad,

with three young kids under the roof now (my brother, Allan, was

born in 1960) and facing a daily hour-long commute, decided to look

for somewhere to live closer to the store. We searched even farther

north, to the very edge of the city, and found a brand-spanking-new

house on Torresdale Avenue in the brand-spanking-new suburb of

Willowdale, which was even more suburban than Downsview; newer

but starker and soulless. Viewed from above, you would have seen a

town planner’s map of some ideal future suburb, the trees mere

saplings, with houses like some Lego construction and little plastic people on the grid-like streets. It was the very edge of town, like in

Pete Seeger’s song “Little Boxes,” where “they all get put in boxes,

and they all come out the same.” All we’d do as teens was dream of

moving downtown where everything was happening, where the

hippies were, where the musicians hung out. The farther you got

from the epicenter of cool, the less cool you felt, and where we

were, you couldn’t be more disconnected from cool.

The mention of “Willow Dale” and “the River Dawn” in “The

Necromancer,” the song Rush would one day write for Caress of

Steel, was a jokey reference to that bland suburbia we were all

trying to get away from - Pleasantville, if you like. And eight years

later, with “Subdivisions,” we were trying to express more seriously

the same dead-end feelings of isolation and almost painful yearning.

Apparently that song rang true for a lot of people - including guys

like the documentary filmmaker Michael Moore, who’s said he

believes it has “actually saved lives.” I’m not sure I’d go that far, but

it has definitely resonated powerfully with a great many individuals

who, listening to it in their identical housing units on the great

suburban matrix, at least realized they were not so alone.

The mention of “Willow Dale” and “the River Dawn” in “The

Necromancer,” the song Rush would one day write for Caress of

Steel, was a jokey reference to that bland suburbia we were all

trying to get away from - Pleasantville, if you like. And eight years

later, with “Subdivisions,” we were trying to express more seriously

the same dead-end feelings of isolation and almost painful yearning.

Apparently that song rang true for a lot of people - including guys

like the documentary filmmaker Michael Moore, who’s said he

believes it has “actually saved lives.” I’m not sure I’d go that far, but

it has definitely resonated powerfully with a great many individuals

who, listening to it in their identical housing units on the great

suburban matrix, at least realized they were not so alone.

Willowdale was more a tile in a mosaic than the idealized

Canadian melting pot of cultural influences. I hesitate to use the

word “ghetto,” considering the real ghetto conditions my parents

barely survived in Poland, but our neighbourhood was made up

mainly of Jewish families, across the tracks from the older farm

community beyond the city limits - the main east-west thoroughfare

of Steeles Avenue. Not all of those folks were pleased to see a

burgeoning Jewish community on their patch; antisemitism was still

rife in those days, handed down to a fresh new generation of hate-

mongering teenagers. The farm boys and other locals were on the

lookout for young ethnics like me to terrorize.

I was a particularly easy target: shy to begin with and self-

conscious about my outstanding nose. I’d already been razzed about

it from time to time, but the abuse was worse now, and growing my

hair long, as I started to at around twelve in my earliest emulation of

my rock and roll heroes, further stoked the ire of those goons. The

neighbourhood was too new to have a junior high, so we were bussed to the nearest one, R. J. Lang Elementary and Middle School,

about fifteen minutes’ drive away. On arrival every day, we “Jews

from Bathurst Village” had to briskly walk the gauntlet across the

yard to the main entrance; if you broke into an actual run, you were

asking to be chased. Sometimes the waiting kids would stand there

unnervingly silent, watching our every move; other times they

taunted us, jeering, “Dirty Jews,” pushing and shoving until fights

broke out - even between the girls. Not exactly the way the world

looks at us nice polite Canadians, eh?

I wouldn't rush to call it antisemitism, necessarily; more than

anything it was a territorial war. These jerks trolling the streets and

hallways for Jews to torment beat on anyone who didn’t fit into their

worldview. They really weren't all that discerning. But come to think

of it, as the Chosen Fucking People we did get singled out for special

treatment. Okay, yeah, I’ve changed my mind. It was antisemitism.

One time in the hallway, as I was bending over to retrieve

something from my locker, I was shoved from behind and rammed

right into it with my head and ears stuck inside, and humiliatingly

had to be helped back to my feet. Another time after school, I was

standing with a friend at a bus stop smoking a cigarette (yeah, lots

of us smoked at twelve back then; if you could puff on an Export “A”

without coughing your head off - which I could not - you were a real

man) and when I threw the finished butt away, a couple of farm

boys strode up and pushed me hard, and one menacingly said, “Hey.

I didn't like the way you threw that away.”

“Uh, okay. Sorry. Sorry,” I said, holding my breath until they’d

walked away. I escaped a beating that time, but on it went. More

often than not we'd be greeted when we got home by knuckleheads

waiting on their bikes at the bus stop to harass us, whooping and

hollering, all the way to our doorsteps. We learned to run pretty

damn fast, I can tell you. We never told our parents, partly because

we didn’t want to admit our fear even to ourselves, but we also

knew that our experience couldn't compare to what they had been

through during the war. Even now they had enough to worry about,

and we didn’t want them to see us as the weak and frightened

students we really were. The consequence, however, was that nothing was ever done to protect us. In those days I was a big fan

of DC comics, especially Superman and Green Lantern, and I

remember wishing, If only I had the power to become invisible, then

I could walk amongst these assholes without being so afraid.

Working-class immigrants like our parents were hard-pressed to

simply put food on our plates. We kids knew no different and for the

most part didn’t care, but there were times when it stung. Not

knowing how to skate, for instance, was an instantly alienating

offence for a Canadian boy and certainly didn’t help a little pischer

like me to assimilate. I was bought a pair of skates but was

otherwise left to learn on my own and spent many a freezing cold

Sunday afternoon shaking off frozen fingers and toes as I dragged

myself around the ice on my ankles. Needless to say, I would never

be anyone's first pick for games of shinny - if I made the cut at all.

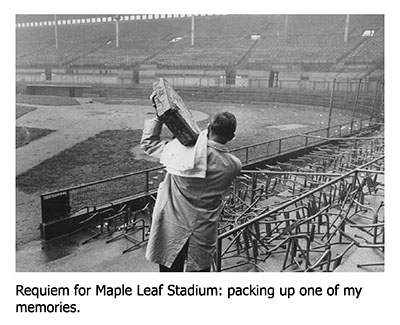

Baseball, meanwhile, was in my bones - long before music

started to seriously divert my attention. There was no major-league

Toronto team then, but on weekend afternoons I’d watch the New

York Yankees on TV, beamed in from stations in Buffalo, with stars

like Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Yogi Berra and Roger Maris, as well

as their rivals, the Detroit Tigers, of whom I was a big fan, and I

remember hopping on the bus and streetcar with my pals for the trip

downtown to watch the Maple Leafs, Toronto's Triple-A International

League team. I must have been just ten or eleven and can't recall

the presence of an adult with us at all, so those memories feel like

my earliest independent moments. Maple Leaf Stadium, at the south

end of Bathurst Street near the lake shore, was a typical minor-

league ballpark of the period, with high bleachers, metal box seats

and wooden benches wrapping around from foul pole to foul pole

and behind the infield. In truth, by the time I was old enough to go,

it had become dingy and rundown and the games were sparsely

attended; it was demolished not long afterwards, in 1968, after the

team had left town to play as an unaffiliated club, grooming players

for various major-league clubs. Nonetheless, photos of the old

ballyard, with banner ads along its walls at the back like READ THE

STAR FIRST FOR SPORTS, EXPORT and STONEY’S BREAD COMPANY, spark nostalgia in me. Those balmy days were among the happiest of my

childhood.

I spent countless hours on our driveway pretending to be a pitcher, throwing a rubber ball as hard as I could against the wall of

our house. I’d say to myself, “I can throw harder ... yeah,” with a

feeling that I always had a faster throw in me - even if I didn't.

When I was eleven, I summoned the nerve to try out for my

neighborhood baseball team, but I didn’t make it and was crushed.

Licking my wounds, I played out the rest of my sports career in the

school playground - much of that time bent over baseball cards, of

which we were fervent collectors. We considered them precious but

flung them around in a game called Close-ies, competing to get

closest to the schoolyard wall, and Lean-sies, where you'd lean one

card against the wall and take turns trying to knock it down with a

well-judged flip of another, creasing the corners in the process. Oh

my god, how it hurts to think that today those cards, in perfect condition, could be worth hundreds of thousands if not millions of

dollars...

I spent countless hours on our driveway pretending to be a pitcher, throwing a rubber ball as hard as I could against the wall of

our house. I’d say to myself, “I can throw harder ... yeah,” with a

feeling that I always had a faster throw in me - even if I didn't.

When I was eleven, I summoned the nerve to try out for my

neighborhood baseball team, but I didn’t make it and was crushed.

Licking my wounds, I played out the rest of my sports career in the

school playground - much of that time bent over baseball cards, of

which we were fervent collectors. We considered them precious but

flung them around in a game called Close-ies, competing to get

closest to the schoolyard wall, and Lean-sies, where you'd lean one

card against the wall and take turns trying to knock it down with a

well-judged flip of another, creasing the corners in the process. Oh

my god, how it hurts to think that today those cards, in perfect condition, could be worth hundreds of thousands if not millions of

dollars...

My dad was not much of a baseball fan, but I do remember

watching Hockey Night in Canada with him - not too often, for it

would be past my bedtime. I’d sneak out of my room and crawl

under the furniture to watch without him knowing, or at least that’s

what I thought, until he’d calmly say, “Gary, go to bed now.” Busted!

But my favourite memory of him and sports was watching him

watching the wrestling. OMG, he would get so effin’ excited. Seaman

Art Thomas, Sweet Daddy Siki, Haystacks Calhoun, Lord Athol

Layton ... man, he loved the shtick. I don’t think he cared whether

it was real or fake at all. He was so into it that he’d mimick the

wrestlers’ holds - so much so that one time he wrestled himself right

off the couch and bang onto the floor.

Summers were lazy and hazy, my siblings and me hanging out on

the streets with all the other unsupervised kids. On Saturdays from

breakfast to lunch, I’d be rooted to the carpet in front of our faux-

wood-panelled RCA Victor, mesmerized by The Bowery Boys, then

The Three Stooges, and rounding out the morning with an array of

horse operas featuring those singing cowboys Roy Rogers and Gene

Autry, or more “authentic” westerns starring John Wayne or

Randolph Scott. Dang, I loved them all. . . still do! Basically, I was

left alone to watch as much TV as I wanted.

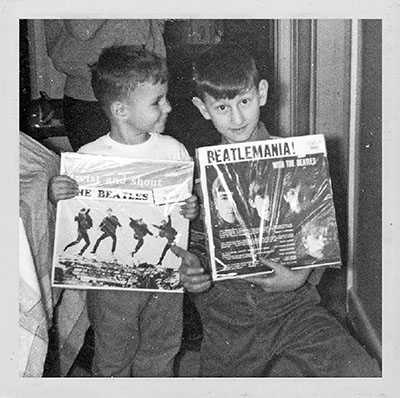

But TV wasn’t only for goofing off. It brought the world into our

living room on Vinci Crescent, from the Cuban Missile Crisis to the

assassination of presidents to - on February 9, 1964 - the Beatles on

their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, and suddenly there

was my sister kneeling on the floor in front of the television, crying

and reaching for the TV screen as if she might touch the Fab Four

and have one of them all to herself. I remember laughing to myself

and thinking, What is wrong with her? but seeing the impact that

rock and roll had on her made a definite impression on me. Needless

to say, Our parents were singularly unimpressed, but rock and roll

music had entered our home and, as my mom would say, “De rest is

history.”

Little by little this nerdy Jewish kid with immigrant parents was

assimilating, blending in and meeting new friends as best I could,

going to new schools and hearing about new bands on an almost

daily basis. North York may not have been the beating heart of the

Swinging Sixties, but we sure wanted to be a part of it. We were

buying records now. The British Invasion had begun - not just the

Beatles, but the Kinks, the Stones and Donovan, and our young

minds were opening up to fresh ideas about clothes and style. I

grew my hair longer, letting the bangs drop over my forehead to

cover my eyes.

Then, on the night of October 8, 1965, my father died in his sleep, and the music stopped cold.

He’d come down with the flu. He was supposed to stay home with

me, as I had it too, but while Mom was readying for work he heard

his carpool buddies honk the horn outside, grabbed his jacket and

ran out to jump in with them. Mom was furious because she was

then forced to take the bus to the store in Newmarket, and when

she got there gave him an earful and sent him home. I remember

being in bed, semi-delirious with the fever and hearing him return. I

remember him asking me how I was. And I remember him heading

off to his bedroom. That was the last time I saw him alive.

I awoke to screams. Struggling to rub the sleep from my eyes, I

saw Mom in her nightclothes crying hysterically, then running out

into the street yelling for help. Pandemonium. Soon our neighbours

filled the house, the police were called, firemen were stomping

indoors and slipping heavily on the stairs. My sister and I sat side by

side in silence on the edge of our parents’ bed, staring, stunned

beyond comprehension, at Dad’s lifeless body, there where he

ordinarily slept - a chilling sight I shall never, ever forget. In time we

were hustled out of the room and I was put back to bed, still

feverish, while Susie was taken to a neighbour's house for the

duration of the madness. I don’t even know where my little brother was or who was taking care of him, but I imagine it was my

grandmother or Mom’s sister, Aunt Ida.

I fell into a fever dream. Some hours later I was roused from

Sleep by my uncles and told to get dressed. Everything was still

manic. People were arguing.

“He should put on a suit!”

“No, look at him, der kint chot a feveh'”

“But he needs to look nice, it’s his father’s funeral!”

This went on all the way down the steps to the black sedan

waiting at the front door. In the back seat on the way to the

cemetery I was lost in a world of my own. When we arrived at the

grave site I was told to wait in the car. It was dusk and raining. I

looked through the window at the huddle of mourners around my

father’s open grave, women sobbing and comforting one another, a

cohort of men in dark coats, led by the rabbi, all shokelling, swaying

on the spot as they prayed. Then two men, maybe my uncles,

Started arguing again as they opened the car door.

“He should come out and say the Kaddish!”

“No, the child is sick, and it’s raining! It will be forgiven if he

doesn’t say it!”

Someone slammed the door back shut and told the driver to take

me home. I looked back through the black rain as that terrible,

somber crowd faded from view.

Morris Weinrib passed away at the age of forty-five. I was twelve.

Outwardly, he’d survived the horrors of the Holocaust seemingly

unscathed, but his heart was damaged by six years of slave labour in

the camps. I believe he'd suffered not just physically but spiritually

too - by which I really mean that he lost his religiosity - if he had any

in the first place. After the experience of the camps, he only put that

on for my mother’s sake. But you know, here I’m just guessing,

because he never shared such thoughts with me. He never told me

what was in his heart. He never told me about his anger towards the

German people or the Nazis or any of that. He never talked about

the war at all, not that I remember. He was always more reticent

about the war than my mom was, and about pretty much everything

else too.

I do, however, have one concrete reason to believe that he’d only

been pretend-religious ... When I was about ten, I accompanied

him and Mom to Eaton’s and Simpson’s, two big department stores

across from each other at Yonge and Queen in downtown Toronto.

As Mom pulled us towards the women’s wear department, Dad said

he’d go for a coffee and a smoke instead (he smoked Export “A”; I

remember distinctly because I thought their green package with the

Scots lass in her tasselled tam was cool). Bored stiff hanging around

with Mom, I slipped away after him, but when I got to the lower-

level cafeteria, I had to stop short on the stairs. There he was at a

table, on his own, with his coffee and cigarette ... eating bacon and

eggs. My eyes nearly popped out of my head. My own dad eating

traif. Then, as I watched him from afar, a sly grin spread across my

face. Not only did I love the fact that I had busted him, but a

heretical idea was planted in my brain that all these religious rules

were bullshit. It was like getting a hall pass, a Get Out of Jail Free

card, and I knew that one day I was gonna use it!

In the end, how I imagine him is assembled from just a

smattering of observations, my own and those of others: quiet until

spoken to, more physical than verbal, except at parties when he was

the life of the party, always the jokester. Everyone in our resettled

family adored him. I have photos of him at parties in which you can

see he's wasted; his eyes are a little less bright than everyone else's,

so I suspect he enjoyed a drink or two. He’d kid with the other

children as much as with me. He’d think nothing of slinging my

cousin Gary up onto his shoulders and horsing around with him. If

somebody farted or if he farted, he would turn to us and go, “Did

you see it?”

He could be hard-headed - you wouldn't want to get on the

wrong side of him - but he was funny, upbeat, hard-working, proud,

fully filling the shoes of the New World Man. He had joie de vivre. He

was able to push aside whatever demons walked around with him.

Maybe he wanted to live a good and happy life but was simply

mugged by a bad heart - a condition that would be fixed today just

like that.

These are the memories I have of him, the slide show in my

head. Among the last snapshots, clear as day, is one from when I

was eleven or twelve: him standing on the porch of our house on

Torresdale, giving me a serious look. I had my bike with me and was

chit-chatting with a couple of girls. He called me over and said

bluntly, “Don’t talk to girls. You’re too young.” Now, although I did

have a bit of a crush on one who lived down the street, I was just a

little schmeckell I had no idea what I was doing. So I guess he saw

a twinkle in my young eyes and felt compelled to give me some

fatherly advice and a wag of the finger. But soon he was gone, and

that was the full extent of the birds and the bees that I ever got

from him. (My mother never, ever went there, so like most kids of

my generation, that was something I'd have to figure out for myself.)

In the end, while I can still picture his expressions both funny

and stern, I’m sorry to say that I can barely remember a single

conversation we shared. There wasn't a lot of time to have one.

Everything in my life came to a stand-still. My mother’s grief knew

no bounds. She was devastated, and although life did carry on, she

never fully recovered in her heart. (Over the years, every visit she

ever made to his grave site left her as inconsolable as the day he

died.) Our household became a_ discombobulated mass of

neighbours, relatives and religious elders coming and going without cease. In the old country before the war, my mother’s side of the

family had been Orthodox Jews, which required them - and

especially me as the eldest male child - to observe strict rules for

grieving. These stages of mourning affected me profoundly and, I

believe, set the stage for my life to come. For, let me tell you, we

Jews know how to effin’ grieve. We are awesome at it, as if misery

were second nature to us.

Immediately after burial, we sit shiva for about seven days,

usually at the home of the bereaved. We cover up all mirrors as a

reminder that this is not about us but the one who has passed away.

We sit on low chairs or remove the pillows and cushions from the

sofas. (I’ve never been able to determine the exact reason for that; I

assume it’s to ensure we are uncomfortable and reminded that loss

is painful.) For seven days, we’re supposed to not leave the house

except on Shabbat to synagogue. We don’t work, shave or cut our

hair. We don’t bathe other than for essential hygiene, don’t wear

cosmetics, leather shoes or new clothing. No _ festivities are

permitted, nor sexual relations (as if!), nor even any study that gives

you pleasure.

After the shiva there’s a thirty-day period of mourning called

sheloshim, an easing back into semi-normal life, but as the eldest

son it was also my duty to say Kaddish, the prayer for the dead,

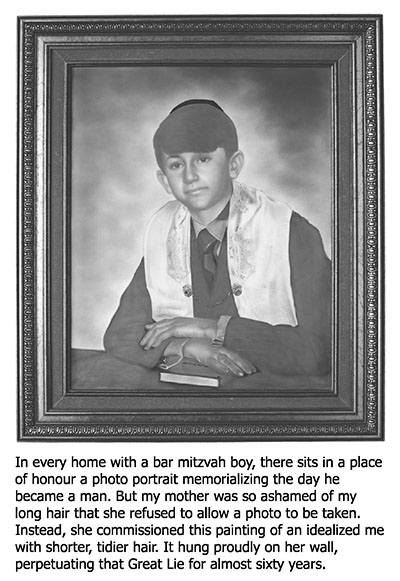

three times a day - for eleven months and a day. This I did without

fail. During such a period, you may partake in celebrations only so

long as there is no music, so when I had my bar mitzvah the

following summer, it was devoid of music and dancing. (Thankfully,

you are not forbidden to accept envelopes of money from

relatives!)

As part of a regular Jewish upbringing, most kids in my ‘hood

went to cheder (Hebrew school) either full time or, like me, after

school between four and six a couple of days a week and on Sunday,

but I hated it. I found it pointless in the world I wanted to live in.

Hebrew was a language that struck me as existing only in dusty

books and scrolls, and I found it hypocritical that the teachers didn’t

seem to care if we understood the actual words - that reciting them

phonetically at the bar mitzvah ceremony was good enough. They were brutal in meting out corporal punishment, throwing chalk at

you for the slightest infraction - not an environment, in my humble

opinion, in which to build a trusting and devoted rapport. The

moment my dad passed away and there was no longer any male

authority figure in the house to enforce my attendance, I resolved to

quit.

Needless to say, my mom was disappointed in me, even

crestfallen. My aunts and uncles berated me for my newfound acts

of independence or, as they saw it, defiance: not just quitting

cheder, but growing my hair longer and hanging around with

goyische friends. One day, even as my family and I were visiting my

father’s grave site, they started in on me. I remember one uncle

saying, “You're killing your mother! You rebel, you delinquent.” I was

to obey without argument, and when I wouldn't they ganged up on

me. Not a single adult relative asked me how I was dealing with my

loss. Other than the occasional aunt who might swipe the bangs out

of my face and say, “You poor boy. Be a good son and cut your hair,”

not one so much as asked me, “Are you okay?” I never fully forgave

them, and have never, ever forgotten the way that one prick of an

uncle crossed the line, while I was standing in front of my own

father’s grave. Fact is, to this day I have a long fucking memory for

people who treat me badly.

My mother’s pain and bereavement sucked the air out of every

room in the house. Please don’t get me wrong: I felt deeply for her

being left with the loss of the love of her life and three children to

protect, a mortgage and a business to run. But it took me years to

forgive my uncles and aunts for their indifference to me at that

fragile time; indeed, part of me never has. I know they were

grieving my dad's loss too, trying to be supportive of my mom while

labouring to rebuild their own families and keep alive traditions that

had been pummelled by the horrors of war. They would never

recover entirely from the Holocaust. But I was only twelve and my

life, too, had changed in the blink of an eye, and it felt to me all too

readily accepted that I - and my sister and little brother - were

simply collateral damage, that we would have to learn to look out for

ourselves.

Enter Max Guttman, a kind, generous and pious man in his early

fifties with a thick Hungarian accent, who as it happened was also

grieving his recently deceased parents. He volunteered to pick me

up every morning and afternoon and accompany me to the Beth

Emeth Bais Yehuda Synagogue, where he taught me how to behave

in shul and how to say all the prayers and sing their mournful

melodies. (A musical influence of a very different kind!) He showed

me consideration and treated me as a young adult learning to cope

with new responsibilities. He also helped me prepare for my own bar

mitzvah in that same year of grieving: “Today I am a man” and all

that.

After a time, I believe that Max started to see himself as a

surrogate father figure. I think he liked me but, like a lot of religious

people, was mainly trying to do what was right for the community

and, specifically, for my mother. But I wasn’t having it. I’d been

growing my hair almost with a vengeance, and one day he took it

upon himself to intercede. On the way home from morning services

he said, “Let me take you to my barber. You don't have to cut it

short. Let’s just clean it up a bit.” Perhaps my mother had asked him

to, I don't know. She'd certainly been bugging me about it as much

as every other adult I knew, including the school principal, Mr.

Church (perfect name, eh?) - a royal pain in the ass, a regular tyrant

who made us stand nose to the wall for an hour or more if he

caught us in the halls with our shirts not tucked into our trousers or

if we dared to grow our hair long enough to touch the back of our

collar. It seems almost quaint now, but Mr. Church, Max, my uncles,

all of them saw hair as the beginning of rebellion and wanted to

crush it, quite literally nip it in the bud before it became a real

problem. So, I sat in the barber’s chair but informed the man as

sternly as I could that I only wanted a trim. He said okay, but then I

caught Max's reflection in the mirror, his hand making a motion to

cut it all off. I freaked, jumped up and stormed away in outrage,

shouting at him that he was a liar and reminding him that he was

not my father. After that outburst, he backed off and our relationship

suffered, which was a shame, because I did feel some kindness and

gratitude towards him for what he was doing for Mom, the time he took to help instruct me and never laying guilt on me as viciously as

my uncles did.

I have to hand it to him, Max was creative. He asked a cantor he

knew to make a recording of the Torah portions I was supposed to

learn for my bar mitzvah. My first gig, I guess! A cantor, in case you

don’t know, is the vocalizing counterpart to a rabbi, the one who

sings the psalms and prayers during the service - a much cooler job

than rabbi if you ask me. So I memorized all the Hebrew words, the

traditional melodies and the vocal nuances off this recording, and on

the day I was called to the Torah I managed to recite the entire

program by heart, sort of pretending to read it. I saw Mom smiling

proudly through her tears in the front row, and my relatives were

now saying, “Oy, such a lovely voice. You should be a cantor.” I

nodded my head and gratefully took their envelopes of bar mitzvah

money while thinking to myself, Yeah, right. But sorry, folks. I'm

done with all of that.

My mother may have been crying tears of joy that day, but there

was no real exploring faith with her or anyone else in my family. It

was all dogmatic and unintellectual. There was nothing to discuss. They simply did as they'd been taught. How dare I even question it?

There was one direction only: doing what Jews were expected to do

and behaving how Jews were expected to behave. Children in the

Old World were to be seen and not heard. Anything more was

disrespectful and a reason to be punished with the stick of shame.

(My mother in particular knew how to wield that stick - with

precision!) Of course, in time I realized that faith for them was a way

of keeping the dead alive, a tribute to them, an assertion that they

had not perished in vain. And in more practical terms, these

Survivors were committed to rebuilding the Jewish population. For

the vast majority of observant Jews, the mantra was and remains

“Get married, have lots of kids and keep them faithful to the

religion.” Thus, it’s not just a matter of the past but the future too.

So, yes, in time, I did come to understand that that’s what drove

them, but I still could not bring myself to feel the same way. Please

understand, I love being a Jew and I’m super-proud of all that “my”

people have accomplished in so many aspects of life - especially in

the face of persistent prejudice, hatred and outright murder - but I

consider myself a devout cultural Jew: I love the history, the humour

and even some of the food! But a belief in God and organized

religion? Not for me. A line from Woody Allen’s Love and Death sums

up my feelings well: “If it turns out that there is a God. . . the worst

you can say about him is that basically he’s an underachiever.”

My mother may have been crying tears of joy that day, but there

was no real exploring faith with her or anyone else in my family. It

was all dogmatic and unintellectual. There was nothing to discuss. They simply did as they'd been taught. How dare I even question it?

There was one direction only: doing what Jews were expected to do

and behaving how Jews were expected to behave. Children in the

Old World were to be seen and not heard. Anything more was

disrespectful and a reason to be punished with the stick of shame.

(My mother in particular knew how to wield that stick - with

precision!) Of course, in time I realized that faith for them was a way

of keeping the dead alive, a tribute to them, an assertion that they

had not perished in vain. And in more practical terms, these

Survivors were committed to rebuilding the Jewish population. For

the vast majority of observant Jews, the mantra was and remains

“Get married, have lots of kids and keep them faithful to the

religion.” Thus, it’s not just a matter of the past but the future too.

So, yes, in time, I did come to understand that that’s what drove

them, but I still could not bring myself to feel the same way. Please

understand, I love being a Jew and I’m super-proud of all that “my”

people have accomplished in so many aspects of life - especially in

the face of persistent prejudice, hatred and outright murder - but I

consider myself a devout cultural Jew: I love the history, the humour

and even some of the food! But a belief in God and organized

religion? Not for me. A line from Woody Allen’s Love and Death sums

up my feelings well: “If it turns out that there is a God. . . the worst

you can say about him is that basically he’s an underachiever.”

The fact that all three of Mom’s children would eventually marry

out of the faith was, in her mind, a heartbreaking failure of her own

parenting skills. Even after I’d become an adult, she tried to guilt me

back into synagogue: she'd say that by not being observant I was

committing a sin against God and betraying my family and all those

who'd died in the war. Jews are really, really good at guilt, no?) But

it was to no avail. I had prayed for the last time. Surprisingly, once

the penny dropped that we were not going to change, she did too.

It’s a testament to her innate intelligence and maturity that she'd

learn to accept and even embrace people for who they are. She'd

grow fiercely devoted to her daughters-in-law and adored them

unquestioningly till the day she died. I find that hugely admirable for someone of her age and with her past, and wonder if I would have

had the strength to change as she did.

My sister also struggled mightily after Dad died. She was the

first-born, his little girl, and clearly had enjoyed a deeper relationship

with him than I; she was fourteen when he passed, already in the

throes of adolescence, and his death hit her that much more

viscerally. She tried to escape the household at every opportunity,

lashing out and staying out worryingly late. As the “man of the

house” (as everyone loved to remind me) I had to stand up for

Mom, which led to more fights. I, too, was itching to escape,

particularly after my synagogue duties were over. I was percolating

beneath the surface, starting to reject adults at every turn, and as

soon as my eleven months of mourning were over, I spent less time

at home and sought out a new breed of friends.

In 1966 I started at Fisherville Junior High in North York, just

walking distance from our house. It was also there that Susie started

hanging out with some tough guys - "Greasers,” we called them. At

R. J. Lang throughout my year of woe, I’d continued to be one of

the school’s most popular punching bags, but in the first semester at

this new place, as I was walking home and one of these kids

grabbed me by the lapels, winding up to make my life even more of

a misery, another kid said, “Hey, leave him alone. That’s Susie’s little

brother.” Whew. Big sister to the rescue!

And then, when I made friends with a guy I shared a couple of

classes with, a good-natured guy with a cheeky grin named Steve

Shutt, the harassment petered out altogether. How come? Well,

Shutty was a rising hockey star, even in grade seven. He was

revered, super-cool, and just by association with him my kosher

bacon was saved. If you’re a hockey fan, you know he went on to

become a perennial All Star for the Montreal Canadiens, part of the

devastating offensive line alongside Guy Lafleur and Jacques

Lemaire, scoring a career 424 goals, and in 1993 was elected to the

hockey Hall of Fame. He was a year older than me, so we had only a

few mutual friends, but we dug the same music and would soon

both develop an interest in the bass guitar. He was growing his hair

then too, and in the sixties, man, those with long hair bonded instantly. (He’d grow it out every summer, cutting it all off again

without hesitation as soon as the hockey season began; he knew his

priorities.) I’m not sure if Steve was actually aware of being my

saviour. We never spoke of it. But our friendship did allow me to

walk amongst the bullies with impunity.

By now, I wouldn't be surprised if you were hoping for the juicy

rock and roll bits, i.e., the story of Rush, to begin. I will tell you all

about it, but I’m afraid that first a few more heavies are in order. In

the next chapter I’m going to relate my parents’ experience of the

war, After all, if it wasn’t for what happened to them then, I wouldn't

be here to tell you my tale now and I wouldn't be the person who I

am. A lot of what loomed over me as a boy went into forging my

own personality, my value system - the good things and the bad. But

most important, I feel both duty - bound and honoured to tell you

their story. For their sake. If you find it half as harrowing to read as I

did writing it, you may be tempted to skip right along. If you do, I

won't blame you and I'll see you in chapter four, but I’ve included it

in this book because I feel we're living in an era that seems to have

forgotten what can and will happen when fascism rears its head. I

think we all need reminding of it in the face of those who either

deny the past or never knew about it in the first place.

When we were children my mom would tell us about her

experiences in the war, and when our uncles and aunts were over,

talk would sometimes turn to theirs as well. It made me angry to

hear what they’d seen and suffered at the hands of the Nazis, and

when I went up to bed my rage would boil over into waking dreams.

Lying in my darkened room, I'd wish that Hitler would magically

appear in front of me so I could vanquish him myself with brute force - with my bare hands, punching and strangling him (in a way

that Quentin Tarantino would approve of). For me those stories cast

deep doubt on the existence of a higher power - certainly one with

an ounce of compassion - and on the very point of religion. After my

dad died, I was like, Hey, God, what have you done for me lately? I

was amazed that my mother came out of such a horror show still

believing.

The story that follows is sewn together from bits and pieces my

mother and other family members have shared with my siblings and

me over the years, as well as some independently published

Survivors’ accounts and books I discovered while doing my research.

As is typical of many eyewitness accounts of events that took place

SO many years ago, particularly ones recalling events as traumatic as

these, some details were hard to pin down, and we must bear in

mind - as Christopher R. Browning writes in the introduction to his

superbly well-researched book: Remembering Survival: Inside a Nazi

Slave-Labor Camp - that “these were childhood memories refracted

through the horrible experiences that followed." Furthermore, all

the family members who survived the war - including my mother,

who kept on trucking until she was almost ninety-six - have now

passed on.

Thanks to the dedication of various diligent Jewish and other

Holocaust memorial organizations, many interrelated accounts have

been recorded in print and on video for posterity. Astonishingly, as I

have found, some of these accounts are from survivors who not only

came from my mother’s hometown but who suffered the same

grueling experiences as she and her family did in exactly the same

places. This has given me the opportunity to cross-reference the

occasional divergent memories. I strongly believe that the stories I

relate to you now are not only true but capture the essence and

spirit of what my mother and father lived through as teenagers - the

awful and the good.

There is, sadly, a paucity of information about my father’s side of

the family. As I said earlier, he never discussed the war with us,

maybe partly because he knew our mom would and did. As a result,

there is little here from his own lips or, for that matter, from his siblings’. He left this world in 1965, and I've gleaned little about him

from the remainder of his side of the family since. What I do have, I

hope I have right.

So yes, there is a bias towards my mom’s version of events for

the simple reason that she was more willing than he to share their

experiences with us. She would talk in detail about all that she and

her family had endured, how time and time again her mother had

saved her life. My mother spoke as if telling these stories to her kids

was the most natural thing in the world. I can tell you that it wasn’t.

Today such parental behavior might be considered irresponsible,

even unthinkable, yet it seemed somehow okay at the time, and I

don’t regret hearing any of it. In her mind, sharing with her children

this six-year nightmare was not just a way of passing her own

history along to us, but a way that we could help the world “never

forget.” What’s more, bizarre as it sounds, it was probably healthy

for her to talk about this stuff, even to her kids. Who else was she

going to tell, a therapist? That was not an option for people of her

generation. Had I suggested such a thing, her answer would surely

have been “Vot, I should pay money to tell this to a stranger?”

LOVE AND HELL SLAVE #A14254

My mother was born in Warsaw, Poland, in July 1925. Her Canadian

passport says Starachowice, but we believe that to be incorrect; she

and her siblings always insisted they were born and lived in Warsaw

until she was five years old. Moreover, her mother, Ruchla (aka Ruzia

or Rose), was born and raised in Warsaw, in the Wielka Wola district,

and was living with her family and working as a_ successful

dressmaker when she met and married my grandfather Gershon

(Gerzson) Eliezer Rubinstajn.

Born in Wierzbnik in October 1900, Gershon was a butcher by

trade. He and Rose had three children, the eldest being my mom,

Malka (Manya or Mary), followed by her younger sister a year later,

Ida (Yita), and lastly brother Herszek (Herschel). They lived in the

part of the city that in 1943 would be the site of the Warsaw Uprising, but they were long gone by the time that violent liquidation

occurred. Gershon had been having trouble finding work, so after a

consultation with their rabbi (to whom pious Jews usually went for

advice of a serious nature), and despite his wife doing very well as a

clothing designer, they decided in 1930 to move the family 160

kilometers south to Starachowice-Wierzbnik, where the Rubinsteins

lived and worked as a close-knit clan, and he joined his mother and

two of his brothers in their thriving butcher business. They found a

good and stable home there, living at number 6 Kolejowa, a small

house across from the train tracks, and quickly resumed life as a

middle-class, highly observant Eastern European Jewish family. (1

was surprised to hear from my mother that she had learned to speak

Yiddish only upon their arrival there; as residents of the bigger, more

sophisticated city of Warsaw they mostly spoke Polish, even to one

another.) My grandfather, a generous man, soon became a respected

community leader, head of a local shtiebel, who would often bring

needy strangers home for dinner on the Sabbath.

Starachowice was separated into two distinct sections by the

Kamienna, a tributary of the Vistula, Poland's largest and longest

river. It was a small but growing industrial city of mines and steel

works, whose factories produced guns for the Polish army before the

war, whereas Wierzbnik was more like a shtetl made up mostly of

wooden houses, and where 90 percent of the Jewish population

lived. That little river dividing the city has been described as a

symbol of regional antisemitism, separating the Jews from the rest

of the Poles; even before the Nazis arrived, the munitions factory of

Starachowice was already off-limits to Jewish employment. Another

Survivor from their town, my cousin Zecharia Grynbaum (Zachary

Greenbaum), wrote in his own autobiography, “The Jews and

gentiles lived together peaceably enough, but the hatred was always

there, burning underneath.” In fact, my uncle Harold recalled that as

the war got closer the Poles of Starachowice grew less afraid to

show their true colours, standing in front of Jewish shops

discouraging people from doing business with “dirty” Jews.

In 1938 rumblings of a German invasion were starting to spread,

yet my family, along with many others, did not give these whispers much credence. Like most of their fellow townspeople they were

caught woefully unprepared for the fall day on which the German

armed forces bombed and marched their way right into their life and

tore it to pieces.

On the afternoon of Friday, September 1, 1939, my mother and

her first cousin and close friend Miriam, both fourteen years old,

were sent as usual to the Starachowice side of the river to buy some

bread for the Sabbath. They were expected to return home before

dark but were still on the road when the bombs began to drop.

Polish soldiers were shouting and scrambling as they leaped into the

trenches built in anticipation of such an attack - though notoriously

there was little resistance - and my mom and her cousin were forced

to hide in one of those ditches. The fighting went on for more than a

day as they cowered there. At daybreak when the city finally fell

quiet, they crawled out from amongst the many dead or injured

Polish soldiers and started walking back to Wierzbnik.

Along the way they heard stories from people about two young

Jewish girls who’d been killed in the raid. They entered their part of

town to find the streets deserted. As my mother describes it, “We

were like the only two people walking in the whole wide world.”

They went from house to house, seeking their families, finally

Opening one door to find their fathers, Gershon and his brother

Josek (Yankel), saying Kaddish for their missing daughters. Being

Orthodox Jews, women were not allowed to pray in the same room

as men, so when the girls entered the house their fathers grabbed

them and pressed them close beneath their tallitim (prayer shawls)

until the prayer was over, then took them to show their wives and

sisters that the girls were still alive.

Within ten days the occupation began. As one resident, Yitzhak

Edison-Erlichsohn, described: “The entire market was filled with Nazi

soldiers. The following day the persecution and torture of Jews

began; kidnapping them for work, frightful beatings, robbery of

Jewish possessions, and the laughter and ridicule of our neighbours

of a thousand years - the Poles.”

The country was now under the strict control of the German

General Government, led by the SS chief, Heinrich Himmler, who in 1942 would be tasked with carrying out the Nazi “Final Solution.”

Under his command the important factories of Starachowice legally

became the Braunschweig Steel Works Corporation, owned and

operated by Reichswerke Hermann Goring.

New rules for the Jews were quickly established and violently

enforced. In an ominous message to the Jewish citizenry of

Wierzbnik, shortly after the Yom Kippur holiday was concluded the

central synagogue of their community was burned to the ground.

Schools were now off-limits to Jews; curfews were imposed, and a

ghetto was being delineated to further limit their movements. Public

degradation of Jews became the norm. The German word for Jew,

“Jude,” was painted on all Jewish shop windows, and it became

mandatory for Jews in public to wear a yellow badge in the shape of

the Star of David, either as armbands or sewn onto their clothing.

Standard operating procedure for the Nazis during an occupation

was to go house to house, removing at gunpoint all adult Jewish

males (or other undesirables) deemed a potential threat to their

command. They would either march them to a secluded location and

murder them en masse or transport them by train to prison, the gas

chambers at Treblinka or some other destination where they would

meet the same terrible end. This was my grandfather Gershon’s

brutal fate.

My mother used to tell us with guilt and regret that before the

Germans arrived her father had an idea to run away to the Soviet

Union, but she was so distraught at any talk of him leaving the

family that he abandoned the idea and stayed on, only to meet his

doom. It’s a pain she had to bear her entire life.

The SS came to their door in the winter of 1940, in the middle of

the night. They ordered Gershon out of bed with a “Get up, dirty

Jew, you're coming with us.” When my grandmother dared ask why,

she was smacked in the face. Gershon, only forty years old, was the

first male of the town to be arrested in this manner. He was marched

off amidst the chaos and the crying and protestations of his family.

My mom ran after them. She caught up and took hold of her father’s

arm, refusing to let go until the soldiers beat her into submission, leaving her unconscious in the snow. Her mother found her there a

few hours later.

Later that day a local policeman who’d been one of Gershon’s

friends informed Rose that those arrested were to be transported by

train to the town of Radom that same evening. My mom and one of

her male cousins slipped out of the house and went to the station,

where they found the men lined up and shackled and waiting for the

train. My mom left her cousin watching from a safe distance to try