|

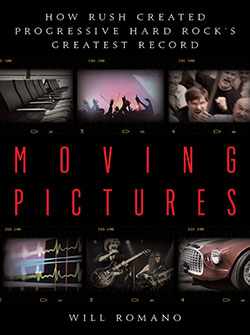

How Rush Created Progressive Hard Rock's Greatest Record Will Romano January 2023 |

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1: 1981: The Last Picture Show

Chapter 2: Big Screen Beginnings

Chapter 3: Enough Rope?

Chapter 4: This Machine Kills Fascists

Chapter 5: Pictures at 11

Chapter 6: ^^^^ Wavelength ^^^^

Chapter 7: Coming Attractions

Chapter 8: Audiovisual: The Perfect Side

Chapter 9: Cinema Paradiso: Side II

Chapter 10: Joan of Arc and Flaming Pie Plates

Chapter 11: The Cold War

Epilogue: Our Vienna (or Paradiddles in Paradise)

Moving Pictures Tour Dates

Bibliography

Discography

Index

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, Neil Peart, Terry Brown, Paul Northfield, Deborah Samuel, Mike Girard, Jason Bittner, Eric Barnett, Kevin Aiello, Uriah Duffy, Andre Perry and Yael Brandeis, Ken Hensley, Pete Agnew, Paul DeLong, Robert Di Gioia, Jonathan Mover, Brian Tichy, Jason Sutter, John DeServio, David Greene, Freddy Gabrsek, Marty Morin, Yosh Inouye, David Marsden, Adam Moseley, Bruce Gowers, Dave Krusen, Brian Miessner, Wanda and Ronnie Hawkins, Frank Davies, Mike Tilka, Len Epand, Rick Ringer, Graham Lear, Rick Colaluca, Gerald O'Brien, Dwight Douglas, Rodney Bowes, John Coull, Moira Coull, Alfie Zappacosta, Monte Nordstrom, Mark Richards, Terry Draper, Steve LeClaire, Craig Martin (Classic Albums Live), John Sinclair, Sandy Roberton of Worlds End, Patrick Ledbetter (CIMCO), Blair Francy, Jane Harbury, Dan Del Fiorentino (NAMM), Steve Tassler, Arielle Aslanyan, Lynne Deutscher Kobayashi, David Jandrisch (Musicians' Rights Organization of Canada), Toronto Audio Engineering Society, Morgan Myler (IATSE Local 58), Tim Kuhl, Graham Betts (Pickwick Group Limited), and Natalie Pavlenko (OCAD).

A special thank-you to my wife Sharon, my in-laws and family members, my brother Michael, my uncle Tony, Aunt Gigi, Mom and Dad, Anthony Bernard, Dave Penna, Bernard Scott, Vincent Tallarida, Michael Richford, Ed Perry, Gary Jansen, Mike Harrison, as well as those who've helped to make this project possible: Chris Chappell, Barbara Claire, Laurel Myers, Bruce Owens, John Cerullo (for taking on this monstrosity to begin with), and everyone at Backbeat Books/Rowman Littlefield. Thank you for the opportunity and your patience.

I dedicate this to Molly, Maggie, and Gilligan. You're forever with me, but I still miss you. Every day. Grateful for the newest member of the family, Scarlet. Grateful for the river.

Thank you, JC.

CHAPTER 1:

1981: THE LAST PICTURE SHOW

The obvious question when reading or even writing a book such as this is, why? Why Moving Pictures? Why expend the time, energy, and other resources on a single album by a Canadian power trio recognized, by and large, as a progressive hard rock band?

I could simply state the company line, that Rush has racked up dozens of gold records, and more than a dozen platinum in the United States alone. And, according to sales figures tallied by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), Rush is third, behind only the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, for the most consecutive gold or platinum albums by a rock band.

Moving Pictures did well in its day and had attained quadruple-platinum status from the RIAA. That was, until April 2021, when the record went five-time platinum, surpassing 5 million units sold in the United States.

All of this stuff looks great as a few lines of a resume, in a record company press release, or in the biographical information offered on a management or a booking agency website. No one disputes these totals, but numbers often leave us cold and don't always tell the whole story or help drill down to the why — and how.

Why was Moving Pictures effective? How did it become so popular?

Follow me as I turn back the dock a few decades.

Close your eyes: Imagine it's 1981.

You have the radio dial set to your favorite rock station in your home, room, basement, car, office, apartment — or wherever. The DJ announces that this is "the new one" from a band called Rush. There's silence for a split second, and then a snarling synthesizer portal opens, and before you have time to react, you're hit with the sonic equivalent of shrapnel — fragments of artillery fire that hit you where you live, changing you forever.

Compression-enhanced sound clamps down on bandwidth of audio, adding a concentrated punch to a funky, murky, groovy, ballsy hard rock anthem. Somewhere, about midway through the track, the sound implodes, or collapses, with short bursts of percussion solos — cymbals crashing, drums thundering — in patterns you've rarely if ever heard in rock music before.

It's unforgettable. A little unnerving. What is this thing?

When the four-minute-and-thirty-three-second track comes to a close, our friendly guide, the DJ, returns to tells you that the song is called "Tom Sawyer," and it's featured on Rush's new record, Moving Pictures.

You need a minute to process what you've heard: first you were frightened, then. exhilarated . . . and now intrigued. Titling the track "Tom Sawyer" seems so anachronistic, so incongruous with the modern sounds that have caught your ears, you can't help but wonder how they were made, the personality profile of the people who made them, and why you feel the way you did.

The near-perfect marriage of music and lyrics seemed so contemporary, even cutting edge. It's thought-provoking music and kind of kick-ass, too: headbanging sounds for music nerds, poetry wrapped up in intellectual rock — and catnip for esoteric adrenaline junkies.

This was Rush, circa 1981.

Many may have had a similar experience the first time they'd encountered "Tom Sawyer" being spun for listeners over the airwaves. The auditory power of "Tom Sawyer" and its rippling synthesizer vortex chewed a gaping hole in the space-time continuum, creating a new dimension that grabs us by the collar and compels us to listen even today.

And "Tom Sawyer" is but the opening salvo for an album that won Rush so many praises and fans In reality, the record helped stabilize and bolster their career.

So, when we ask, why Moving Pictures?, the answer lies in tapping into the same exploratory energy that fueled the instinct to chase that first scare, that initial thrill. Like watching the best suspense movie you've ever seen, you pursue that "high" in the hopes of recalling the same emotions and reliving the moment of discovery. By examining several factors, or tributaries — or, in movie terms, plodines — that contributed to the success, making, and appearance of the album, we might discover why Moving Pictures remains so vital in the twenty-first century.

Nothing is created in a vacuum, and the three members of the Canadian progressive hard rock band — bassist/vocalist/keyboardist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and drummer/percussionist and lyricist Neil Peart — were influenced by a great number of musical genres over the years. These cultural tributaries powered the creative process and funneled into the anatomy of the musical work at question, Moving Pictures.

A main thematic tributary coursing through Moving Pictures, as its title suggests, is the filmic properties the seven-track album possesses. The overriding principal of music, as Jimmy Page once said of Led Zeppelin's catalog, is "synesthesia," "creating pictures with sound."

Indeed. Moving Pictures was conceived as a collection of independent stories, cinematic vignettes, captured by three very different but relatively experienced young men using advanced audio equipment and their inherent creative instincts, which resulted in a complete, coherent work.

Unparalleled in the band's recorded output, Moving Pictures boasts multisensory qualities: the famous snarling synth portal we'd discussed ("Tom Sawyer"); the pulse-quickening cyclical patterns corkscrewing through the genre fluid "Vital Signs"; a spine-tingling sci-fi thrill ride thinly masking social commentary ("Red Barchetta"); technically precise musical jousting amid time signature changes ("YYZ"); chilling glimpses of a hellish, torch-lit mob haunting "Witch Hunt"; the wide-screen dual optics of "The Camera Eye"; and a ferocious guitar tone taking a bite out of fame ("Limelight").

Layering tracks, knowing when to use guitar effects (and when not to), various panning techniques used during the mix, and digital production methods, not to mention Rush's sharpened technique and songwriting craft, created a song cycle that's sonically transparent but offers the impression of depth. It's as three-dimensional as Rush's music had ever gotten to date and perhaps ever.

Like cinematographic blocking, the art and science of capturing movement on film, if the action is framed correctly for the lens, the viewer receives a sensation of three-dimensional space. In this case, the band and the production team of coproducer Terry Brown and lead recording engineer Paul Northfield were masters of sonic geometry.

There's a promise fulfilled with the appearance of Moving Pictures as both a manifestation of the impact of the counterculture and the impact of film and music on the counterculture. Historian, author, and educator Arthur Schlesinger Jr. once noted that the counterculture youth of the 1960s "find in music and visual images the vehicles that bring home reality."

Vaguely hinted at with Rush's previous studio album, 1980's Permanent Waves, Moving Pictures can be interpreted as a piece of neorealism, the very stuff of influential cinematic movements, compared to the sci-fi and fantasy epics of the band's past. Liminal on its front edge ("Tom Sawyer" and "Red Barchetta"), the album balloons to full-on realism, with tracks such as "YYZ," "Limelight," and "Vital Signs."

Yes, the fictional, fantastical, and phantasmagorical exist in Moving Pictures, but so does the personal, which intermingles with these elements, sometimes within the framework of a single song, making for one hell of a thrill ride.

The leadoff track, "Tom Sawyer," acts as a kind of overture, setting the lyrical, musical, and thematic tone for the record. Moving Pictures is passage to a new dimension, one in which "Tom Sawyer" cracks the portal open and mythology elevates to the real. This anthem to the modern-day outlier, the nonconformist, whose default position was one of self-reliance, independence, free thought, even defiance, contained as many earth-shattering philosophical implications as groundbreaking sonic properties: it redefines the outlaw motif and the contemporary definition of iconoclast within a difficult-to-pigeonhole musical framework.

Partly inspired by one of America's greatest satirists, "Tom Sawyer" is not only American — it's friggin' American. You almost can't get more American than Tom Sawyer and Mark Twain. By extension, the song is the quintessence of North American rock, nay, North American progressive rock.

In Twain's original novel, Tom Sawyer is an irrepressible youth who has others gift him for the privilege of painting his Aunt Polly's fence or, after running away and pretending to live life as a pirate, shows up at his own funeral. But Tom does grow up (somewhat) throughout the novel and eventually performs a civic duty, as most adults do. This nod toward personal responsibility was one that Twain generally skirts in the novel, but before our eyes, Tom Sawyer did the responsible thing.

Moving Pictures, then, in its own way, reflected a band matured. Indeed. Moving Pictures was Rush's last picture show, the record that marked a coming of age in the wake of numerous musical, cultural, and personal upheavals in the mid and late 1970s. Rush so elevated their game that their music had risen to the realm of the audiovisual.

"Red Barchetta" may be one of the best, if not the greatest, example of the band successfully blending varied emotional content and visual information inside a single song. The sound of the middle section is evenly paced and spaced, like the broken yellow dividing lines of the highway. We're aerodynamically screeching toward an unknown destination.

The third song, an instrumental titled "YYZ," a jazz-rock juggernaut with a hint of Eastern modalities, captures the excitement of the exotic travel but also represents the liberties of modern transportation. Shuttling us to distinctly different compositional sections but also looping us through cyclical parts, the song becomes the thing it represents: a journey full of expectation, wonderment, and, ultimately, release and euphoria.

The aura cast around the East and Eastern musical modes gripped the progressive rock and psychedelic rock imagination, inspiring such innovative popular artists as prototypical progressive popsters the Beatles and later Led Zeppelin, who were seduced (if only a smidgen) somewhere along the way by the progressive rock movement.

The Morse code pattern opening "YYZ" is unvocalized language providing a beacon for safe terrestrial travel, which echoes the distant signals of early progressive rock movement. This repetitive, rhythmic cipher rings in sympathy with the blinkin', seemingly extraterrestrial transmission heard at the opening of Pink Floyd's "Astronomy Domine," from 1967's The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and the aquatic radar-like pings of "Echoes" of 1971.

While it speaks to progressive rock nascent stirrings, at the same time, "YYZ" is also part of the rich tradition of the Western world's mid-twentieth century instrumental pop singalong — tracks such as "Tequila," "Walk Don't Run," "Apache," "Telstar," "Guitar Boogie," "Wipe Out," "Green Onions," and, honorable mention, "(Ghost) Riders in the Sky" (often performed as an instrumental).

Dig deeper into the unknown origins of instrumental music, reach back into a dark epoch in which rhythm and sound fused, and Rush's "YYZ" is absolutely monolithic, essential, even primordial. Except Rush wasn't rockin' a lyre in Syria and communicating via cuneiform on clay tablets in dedication to the goddess Nikkal. Rush was redefining instrumental music for generations to come.

What makes "YYZ" so unique is that it somehow remains grounded in Canadian soil — or, at the least, circling Canadian airspace. While on tour with Rush in the mid-1970s, Peart read Richard Rohmer's novel Exxoneration from 1974, a fantastical tale of the takeover of Canada by the United States.

"We're proud of Canada" Peart told RPM magazine in November 1976. "But nationalism has tenuous bounds. It has to be kept in balance."

Although Peart's stance on nationalism later became crystal clear with "Territories," from 1985's Power Windows, what "YYZ" accomplishes is the near impossible: It drapes the Canadian flag over sonic travelogue.

The last song on the original side 1 of the vinyl LP, "Limelight," preaches that self-exile and isolation are preferable to the phoniness of celebrity and fame. Those who continue to live their life and wish to find meaning or lasting relationships or true invention should do so, far away from stage lights.

Despite its title, "Limelight" isn't about the act of performing music per se but how fame intoxicates both the performer and the acolyte alike. Celebrity corrupts, derailing the process human beings possess for rational thought, such as it is.

This converges with and diverges from Rush's earlier song about fame, "Best I Can," from 1975's Fly by Night, penned by sometimes lyricist Geddy Lee. In the song, Lee welcomes rock and roll stardom while simultaneously attempting to denounce phonies.

Ironically, the themes Rush sings about in "Limelight" wind up coming true and further defining Peart's rather pronounced stance on fame and privacy.

In press photos of Rush from the late 1970s, drummer Neil Peart is shown wearing a suit jacket on which he'd pinned a button featuring the image of a bicycle — a symbol of freedom related to the English television series The Prisoner, starring Patrick McGoohan as a former British intelligence officer. Judging by many of Peart's statements to the press, the idea of being a "prisoner" of the music business, perhaps even a band, helped contribute to the need to write "Limelight."

"Don't get into a situation you can't control," offered Peart to a reporter for the Kansas City Times newspaper, who asked him to provide words of advice for up-and-coming rock musicians. "All you have to do is be aware and use your head."

Whatever pretense the band had toward reclaiming their anonymity in the face of the rock and roll lifestyle was, perhaps, gone forever once Moving Pictures was deemed a great success.

Rush easily slipped into their iconic status:

The bespectacled singing bassist, the one the St. Petersburg Times had claimed possessed as shrill a voice in pop music as Frankie Valli (the Montreal Star went as far as to detect "heinous sounds" emanating from Lee's vocal microphone), was no longer just another front man• he was multitasking, triple-threat Geddy Lee.

Alex Lifeson, the fleet-fingered dude who traded in his vintage-style Gibson guitars for custom Fenders, had transformed himself into a gear and effects guru, a sage of secret and sacred guitar tones.

Neil Peart, a blur of moving arms and swiveling head behind a fortress of red-coated drum shells, was "the Professor," whose acolytes and apostles deciphered his poetic words, committed every piece of his drum gear to memory, and tracked the evolution, in minute detail, of his drum solo throughout the decades.

In his book on Patti Smith's Horses, professor and author Philip Shaw forwards an interesting theory, positing that "death and transformation of the rock god is regarded as an essential, even desirable, condition of cultural change."

Consider this: Roger Waters and Pink Floyd were disintegrating right before our eyes by the early 1980s. Although Floyd had reached stratospheric commercial success by the mid-1970s with The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here, Waters had become withdrawn from the public, even from his own bandmates. The Wall, released in 1979, was inspired largely by this sense of alienation. Dysfunctional and broken, hardly working together as a unit, Floyd released only one more studio album with Waters.

The old guard was dismantling. While Rush was on tour in 1980, playing music that would appear on the upcoming Moving Pictures album, Zeppelin drummer John Bonham died unexpectedly on September 25, 1980. Zeppelin was effectively over, opening up opportunities to younger artists, such as Zebra, who had patterned their approach on the iconic British band's mixed-genre grandeur, and even those who had only briefly flirted with the Zep sound (Billy Squier).

Furthermore, Rush was beginning to taste stardom when former Beatle John Lennon died. On December 8, 1980, the night Lennon was fatally shot outside his New York City apartment building, the Dakota, Rush was in the studio working diligently to complete Moving Pictures.

Lennon, who had cowritten with chameleon rock star David Bowie the song "Fame," a number one U.S. hit five years earlier, often struggled to balance his personal and professional lives while preserving a sense of identity. The difficult and painful lesson of Lennon's untimely death at the hands of Mark David Chapman forces us to reexamine notions of celebrity and privacy. Pearl's words for "Limelight" were prescient to say the least.

Side 2 of the original vinyl release opened with the eleven-minute-long "The Camera Eye," inspired in part by John Dos Passos's novelistic trilogy U.S.A. Lyricist Peart makes a daring commentary about breaking loose of a kind of collective mind-set, one in which we're cognizant of the natural wonders around us.

The greed, corruption, criminality, and personal failures we find in many characters of Dos Passos's epic trifold narrative reflect the moral deterioration, a spiritual rot in the first half of twentieth-century America. Although sanitary by comparison, Peart's lyrics force a refocus of humanity and seems to indicate that the people he observes on the streets of two major world-class cities are missing something, too.

"The Camera Eye" is the final long-form composition to appear on a Rush studio record. Although with 2007's Snakes & Arrows and 2012's Clockwork Angels Rush had seemingly relearned the value of composing lengthier tracks, nothing on these records was in the same ballpark as "The Camera Eye." For this reason alone, it's a milestone and marks a beginning and an end — the alpha and the omega of Rush's progressive rock era.

The following song, "Witch Hunt," also represents an alpha and omega paradigm of sorts. Epitomizing the dangers of mob rule and groupthink, "Witch Hunt" was the last installment of a musical saga titled Fear (then envisioned as a trilogy until a part 4 emerged years later). Despite being part 3 of Fear, "Witch Hunt" was, paradoxically, the first to be recorded Although fellow Canadian prog/album-oriented rock group Saga had already begun recording portions of their often-impenetrable "Chapters" puzzle-like plotline and doing it out of sequence, very few narrative arcs were handled in a similar way in a rock setting.

Listeners would feel their spine tingle from the creepy crawlies of part 1 of Fear ("The Enemy Within," from 1984's Grace Under Pressure) and groove to the hypnotic bounce of "The Weapon," part 2 of Fear — an ode to mass manipulation featured on 1982's Signals studio album.

"Vital Signs," the final track to be written for the album, fittingly aligns with contemporary minimalism, New Wave — esque synth sequencing, reggae, and a dash of grog rock. It's unlike nearly anything the band had previously recorded. For that matter, the clarity of vision exhibited in "Vital Signs," particularly on the topic of individuality, has rarely been matched since Moving Pictures.

Whereas "Natural Science," from Permanent Waves, extols the virtues of honesty and integrity in the face of scientific progress, "Vital Signs" hits similar notes, urging us to preserve what makes us what we are in the cyber present and near future.

As diverse a collection of songs that Moving Pictures is, these entries have one thing in common: together, they compose an anthology of mini-movies that have been conceived, coproduced, directed, blocked and framed, written, and starred in by Rush. Finally, Rush blends all these tracks together, as any great film editing team would.

It's not surprising to find that Rush was using film as a kind of creative fuel. Spooling in the background during the making of Moving Pictures was David Lynch's Kafka-esque 1977 horror flick Eraserhead — hardly an anthem to self-reliance and responsibility.

Although it would be a stretch to claim many similarities between Lynch's psychological and symbolic work — and themes inherent to Moving Pictures — the noir aspects of parenthood have some relevance to the birthing process Rush underwent to record a rock album. Other connections may be difficult to report if not avoid: Geddy had recently become a father, and perhaps he saw his fears reflected in Lynch's surrealistic, if at times gruesome, cinematic vision.

"In the official videos for the album you can see a poster up on the wall of Eraserhead and that was there throughout the whole of the making of Moving Pictures," says recording engineer Paul Northfield. "It was a film that they had seen on their tour bus. They thought it was hilarious. The guy from Eraserhead [Jack Nance who portrays the character Henry Spencer] was the mascot for the album."

Sonically and thematically, the songs hang together well. Indeed. Rush seemed to settle into a root key shared by many of the tracks on the record. In 2012, Guitar Player magazine pointed out that with Moving Pictures, the keys of E and A duke it out.

Doesn't all this mean that Moving Pictures is a concept album?

We would have to reply in the negative if the classic rock opera is the model or template. The material on Moving Pictures is unlike the plot twists and emotional landmines hidden beneath the surface of the Who's Tommy, for instance. By the same reasoning, it's dissimilar to Genesis's The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, from 1974. The record's snaky, mystical narrative was difficult to decipher, but an overriding story arc exists nonetheless.

That isn't to say that Moving Pictures fails to deliver a coherent message. It's a time capsule, a snapshot if you will, of the very moment the band ascended to rock stardom. It also denotes the end of a cycle of progressive hard rock albums for Rush, a clarion call for the musical possibilities they'd explore in the 1980s.

Spurred on by the success of Permanent Waves, a clear break from the hard-core progressive releases A Farewell to Kings and Hemispheres, Rush fell in with the flow of change and the pulse of the times.

Moving Pictures was created in the first summer of a new decade. Applying terms from lexicon of the Seinfeld universe, the time frame from 1980 to 1981 was indeed the "Summer of Rush."

"It was early in their career and being early, it is the best time," says Andre Perry, in whose studio, Le Studio, in Morin-Heights, Quebec, the band recorded Moving Pictures. "I'm not saying the other albums are not as good, but Moving Pictures was the peak of their career."

Rush had, of course, been making professional recordings for years prior to Moving Pictures, but for many, it is this album that represents their introduction to the band — and maybe for good reason. As the guys had often said, their music provides (and provided) a kind of sound track both with regard to Geddy, Alex, and Neil but also for their fan base.

"Given my druthers, I would make out first album Moving Pictures," Peart told Martin Popoff for the book Contents Under Pressure. "I can't think of a single reason not to do that."

"Given my druthers, I would make out first album Moving Pictures," Peart told Martin Popoff for the book Contents Under Pressure. "I can't think of a single reason not to do that."

It would be difficult for anyone, much less the band, to argue to the contrary that Rush didn't strive for a level of success. However, fighting to become successful — battling a hostile press, an often-shortsighted label, fickle popular tastes, concert promoter and radio programmer bias, and so on — is only one aspect of the Rush story.

This account details the band's rise to stardom and the band's balancing act of the personal and professional; everyman personas and rock stardom; keyboard technology, technical excellence, and accessible hard rock; and commercialism and progressive rock.

For Rush, it was always a question of balance.

Our world likes black and white. Be one thing, not the other. If you are one thing, you can't be the other. In order to win friends and influence people, Rush performed a delicate and very public balancing act.

When writer Anne Leighton interviewed Geddy Lee for RIP magazine in 1989, it was apparent that he was aware that the band's music doesn't fit into a neat categorical box.

"Our sound has changed so much over the years," Lee told Leighton. "It's funny. When you talk to metal people about Rush, eight out of ten will tell you that we're not a metal band. But if you talk to anyone outside of metal, eight out of ten will tell you we are a metal band.... But if you have to label us, hard rock suits us better. It's not as limiting as metal, especially if you label it progressive hard rock."

Because of the time period in which Rush gained momentum in the mainstream and because they played amped-up electric guitar (or their concerts were too deafening for critics), they were mistakenly categorized as heavy metal.

Deena Weinstein, in her book Heavy Metal: The Music and Its Culture, points out that metal is a style of music in which "intense" vocals rest side by side with heavily distorted amplified guitars, specifically those played with fervor. "There is no doubt that as early as 1971 the term 'heavy metal' was being used to name the music characteristic of the genre's formative phase," Weinstein wrote.

Music scribes began labeling all manner of rock band — from Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath to Uriah Heep and Deep Purple — "heavy metal" whether they'd earned this tag or not. Others, such as MC5, Iggy and the Stooges, Pentagram, Alice Cooper, and even the Kinks, contributed to metal, but, like Rush, many of the above-named artists were pigeonholed by the industry.

"The best story I have is from the second album, Salisbury, for a song called `Lady in Black', which I wrote during a U.K. tour, and was two chords and a chorus with no words in it," Uriah Heep's Ken Hensley told me before his death in 2020. "It's the biggest single song we've ever had globally. It became a huge hit in so many huge markets, except for America. The most unlikely thing, because it is like a folk song, and the band added a rock touch to it. At first the band didn't want to record it, because they said, `Nah, that's a folk song. We don't so folk songs.' The producer [Gerry Broil.] said, 'Now you do write folk songs, and we'll record it ... ,' and thank God we did, because it was a launching pad for the band from the second album onwards."

Exactly where the phrase "heavy metal" first appeared in print and why has been the basis of parlor games for the past five decades. Some say it was William Burroughs, the English music periodicals, or the lyrics of Steppenwolf's top-two hit "Born to Be Wild" (not to mention the press it generated in Creem magazine), which attempted to capture the physical vibrations of a motorbike or automobile rumbling down the road. Creem later used the phrase "heavy metal" in its 1971 review of Kingdom Come, a record by New York's Sir Lord Baltimore, coproduced by Eddie Kramer, Jim Cretecos, and future Bruce Springsteen manager Mike Appel and issued via Rush's American distributor, Mercury Records.

So, if the origins of heavy metal are a bit murky, one has to wonder about the wisdom and value of categorizing any kind of music at all.

Weinstein suggests that through the 1970s, bands that were melodic but still rockin', such as Aerosmith and Kiss, were labeled "hard rock" to separate them from other "heavier" acts. Some of this, I would add, may have to do with North America's quickly conglomerating rock radio format. Rush certainly fit the more melodic end of the hard rock spectrum, even though they too used noise/distortion, guitar amplifier feedback, and driving or thunderous beats.

As we — and the music industry — ambled into the 1980s, metal became increasingly synonymous with power, volume, speed, and vocalists honing their voices into sharp growls. If these characteristics ever applied to Rush, then certainly, by Permanent Waves and, of course, Moving Pictures, the three guys from Canada were moving away from them.

Irony of ironies: Moving Pictures became popular just as the New Wave of British Heavy Metal began barking at the moon. Metal's dominance as a musical form throughout the 1980s awakened the collective consciousness. Rush wasn't British, of course, but there may have been some residual appreciation for the band's harder or heavier sides from those who remembered the rip-roaring moments in their repertoire, such as those in "2112," "Bastille Day," and "Anthem."

The fact is that Rush's style circa 1981 was owed less to their contemporary heavy metal cousins and more to the popular sounds of rock a decade and a half prior to the release of Moving Pictures.

Rush's raison d'être can be traced back even further, to the realm of the psychedelic power trios — Cream, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and Blue Cheer. (Some historians and rock fans have included bands such as the Who and Led Zeppelin in this class, as they were power trios fronted by a lead vocalist.)

"I was hugely influenced by Eric Clapton when I was young, at the time of Cream," Alex Lifeson once told me. "Being a three-piece band, that was definitely an influence on us."

But as psychedelia slowly dissipated, new subgenres emerged. Modern compilations, such as the Brown Acid series from RidingEasy Records (in cooperation with Lance Barresi, co-owner of Los Angeles — based Permanent Records) and Darkscorch Canticles, issued through Numero Group, explore shadowy corners of the post-hippie North American psyche, largely accomplishing what Nuggets had for proto-punk vinyl collectors and enthusiasts. Rummaging through rock's dusty attics and basements helps to present a historical bridge between psychedelia and hard rock or, if you like, "heavy metal."

The mere presence of these compilations illustrates a shift in consciousness in the waning days of the Vietnam War, the coming political storm of Watergate, and also in a decline in the use of LSD as a recreational substance. As hallucinogens fell out of favor, casual and habitual usage yielded to harder drugs. With it, a less psychedelic strain of rock emerged, quickly relegating hallucinogenic music to the obsolescence bin and giving rise to hard rock and the hybrid psychedelic hard rock.

Rush's sound aligned itself somewhere along the way with psychedelic hard rock and progressive rock, as evidenced by the extended songs "The Necromancer" and "By-Tor and the Snow Dog," both from 1975. Rush straddled the line between the progressive rock and the psychedelic hard rock sound.

When the great splintering of psychedelic rock occurred, one of the extant off-shoots, progressive rock, began building steam in Europe. From British bands, such as Pink Floyd, the Nice, Yes, the Moody Blues, King Crimson, Family, Van Der Graaf Generator, Clouds, and Jethro Tull, as well as some notable American ones (Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention and Touch), progressive rock emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s — a postmodernist mash-up of classical, rock, blues, folk, studio and electronic experimentation, and much more.

Eventually, Rush learned to mix many of these genres too, perhaps in ways that few of the above mentioned did. Arguably, albums such as 2112, A Farewell to Kings, and Hemispheres didn't fit into any category previously established. The music wasn't composed of endless jams or deliberately ambient or spacey passages. Nor was much of it baroque. But there were some massive compositions, sometimes clocking in around twenty minutes and rivaling classical's epic scope, plenty of technical prowess, layers on layers of guitar tracking, and a wilderness of odd time signatures.

Rush's efforts, from 1975's Caress of Steel to 1977's A Farewell to Kings, the following year's Hemispheres, and, to a degree, moments of 1980's Permanent Waves, such as "Natural Science" and "Jacob's Ladder," would not have existed without progressive rock and its impact.

Why? Let's take a brief look at prog rock when it had hit its commercial peak, just a few years prior to the appearance of Moving Pictures.

If one album is emblematic of everything British prog got right (and mostly wrong), a record that encapsulated the subgenre's transgressions, creative ambitions, liberal use of keyboard technology, meandering concepts, musical beauty, and fusion of technique and melody, it's Yes's sprawling double LP Tales from Topographic Oceans — released at the height of prog rock commercial success/excess, late 1973.

Its companion release, Emerson, Lake & Palmer's Brain Salad Surgery, unleashed just weeks earlier, wrapped itself in packaging boasting illustrations of sexualized bio-morphic torture devices, courtesy of H. IL Giger, and manifesting the counterculture's dark impulses and premonitions.

Brain Salad Surgery admonishes us on the dangers of an artificial society, a message that gives us a glimpse of mechanical Armageddon — a prophecy foretold by the counterculture. This apocalyptic view was, no doubt, a partial by-product of the counterculture's preoccupation with soulless machines, fueled by a paranoia of the evils of technology, atomic bomb panic, fear of nuclear fallout, and more than a century of post-Frankenstein cautionary tales warning us of the dangers inherent to poking and prodding nature through so-called advances in scientific research.

Conversely, Tales beckoned us to throw off the shackles. The record's often esoteric messaging hinted at the attainment of spiritual enlightenment — a drilling down through layer on layer of learned behavior to unearth ancient, lost knowledge of the divine (i.e., the "song"), something that's been embedded, perhaps even programmed, into our collective memory.

Both Tales and Brain Salad Surgery fomented in the crucible of 1960s flower power that defined, in their own way, what it meant to be human. Rush's post-counterculture entry Moving Pictures, from 1981, also explores what it means to be human by injecting a neorealism and a confessional voice into the band's music that had been only faintly heard in commercial progressive rock prior to the record's release.

Both Tales and Brain Salad Surgery fomented in the crucible of 1960s flower power that defined, in their own way, what it meant to be human. Rush's post-counterculture entry Moving Pictures, from 1981, also explores what it means to be human by injecting a neorealism and a confessional voice into the band's music that had been only faintly heard in commercial progressive rock prior to the record's release.

Moving Pictures procures some of the best elements of these (and other) progressive rock records from England in the early and mid-1970s, including Genesis's Selling England by the Pound, Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon, and even the faux narrative and synesthesian qualities of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

By 1981, Rush had begun streamlining their musical approach, abandoning, for the most part, the complicated twenty-minute epics, and, in fact, Moving Pictures appeared at a time when the popular appeal of progressive rock from Britain (and North America) had waned and a newer more brash form of heavy metal — speed and thrash — was formulating.

Moving Pictures stood at a precipice: not truly progressive rock, not totally hard rock, and not, as we'll see, New Wave, either. It seemed to erase so-called lines between these musical genres while also boasting some of the best aspects of them.

"Moving Pictures is a good example of a function of the times," says producer and recording engineer Paul Northfield, who would work with Rush on Permanent Waves, Moving Pictures, and the live album Exit . . . Stage Left, among others. "That album arrived at a time when progressive music, in the Yes era, had peaked and we had gone through the punk era. The thing about Moving Pictures is it brought a power to progressive rock, and it was also a period that Rush were simplifying a bit and getting in all the incredible playing but not writing twenty-five-minute songs. That was peaked with Hemispheres and 2112. Now they were focusing and sheer power, as a power trio, with very simple orchestration from very simple keyboard parts."

That's the rub. Despite punk/New Wave's impact in the United Kingdom and the United States and even a small scene in Canada (i.e., Vancouver-based D.O.A., Viletones, the Mods, the Ugly, and the Diodes, among others), progressive rock still held some fascination for the popular psyche.

"Punk got crammed down our throats," explains drummer Paul DeLong, a veteran skinsman who has worked with a variety of artists in the past several decades, including Canadian prog popsters FM. "I liked Joe Jackson and Elvis Costello, but some of the bands that played like amateur garage hacks really bothered me. I guess that was the point, but I didn't like it. I was still going to see Gentle Giant at Massey Hall and listening to fusion. People will always listen to what they want to listen to, regardless of popular trends. The fact that Rush became so huge without hit singles attests to this fact."

"I think that the evolution of Rush was timed perfectly," says Rick Colaluca, drummer for Texas-based thrash metal band, WatchTower. "Like you said, there was somewhat of a void to be filled in the progressive arena, and Rush was right there to meld a heavier sound with progressive elements and take the whole thing to a new level. They were heavy enough to appeal to the hard rock and metal crowd, progressive enough for the music nerds and approachable enough for a much wider audience. That was exploited to its fullest when Moving Pictures came out with a genuine radio hit in Tom Sawyer.'"

And with Led Zeppelin calling it quits after the untimely death of drummer John Bonham many of the bands that critics — and the public in general — compared them to were fading.

"In the beginning Rush had more of a Zep thing going on, and then they got deeper into prog and experimenting," says drummer Brian Tichy (Billy Idol, Foreigner, Whitesnake, Steven Tyler, Ozzy Osbourne, and Vinnie Moore). "After that, they tightened it up and got a little simpler and radio-friendly, I suppose. But Rush always had a way of gaining fans that were more 'metal' and 'hard rock' and `prog.' They wrote music that had those elements underneath their 'Rush Umbrella.'"

Was Rush fated to release Moving Pictures when they did?

"Nothing at that time had such a unique blend of songs that had great melodies composed by musicians with such mastery of their instruments," says drummer Dave Krusen (Candlebox, Pearl Jam, and Unified Theory). "I think that's why they resonated with metal heads too. It blew so many people away, how well they did it. There were other prog bands, but Rush had everything going at once."

Punk rock still had its die-hard fans and true believers, but the mainstream public's taste for fast and loud was apparently satiated by metal and its ever-developing variants. Those predisposed to a different and, let's say, European style of rock gravitated toward the minimalistic and industrial sounds of post-punk New Wave. Well, that is, if crossover from punk happened at all.

Rush was reshaping their sound accordingly based on their interpretation of these forms. There's no denying that tastes of rock fans were changing in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But how much of this change can be attributed to zeitgeist, slick marketing, consolidation of radio programming, listener fatigue, labels looking for a higher return on investment, or the industry searching for the "next big thing"?

Whatever the reason, Rush seemed to read the tea leaves correctly. For instance, Human League's megahit Dare! would soon dominate the early 1980s. Released in the United States in 1982, "Don't You Want Me" became an international hit — a song framed largely by a LinnDrum, an electronic device that could be programmed to produce unwavering beats.

After Joy Division front man Ian Curtis committed suicide in 1980, the band regrouped as New Order and released their debut, Movement, in 1981 on the Factory label. As author Chris Ott points out in his book on Joy Division's debut album, Unknown Pleasures, producer Martin Hannett had the technical ability and willingness to experiment with and finesse audio equipment to, in essence, create new sounds from existing tracks, something he did for the guitars and drums for Unknown Pleasures.

Through ambience, sound effects, and digital delay, Hannett and the band practically invented a new subgenre, allowing a punk esthetic, luminescent electronic sounds, hard rock, and techno pop to intermingle, which greatly differed from the more in-your-face sound of the band's concert performances.

Rush absorbed what was happening around them, listening to these sounds as well as recorded output of others, such as Ultravox, Japan, and post-Genesis solo artist Peter Gabriel, and even found themselves branching out as listeners and gravitating toward so-called world musk — the Caribbean flavoring of reggae and artists such as Peter Tosh and Bob Marley and the Wailers.

The name of the game was short, good, catchy, and, to a degree, electronic. And who could argue? Even something as earthy as dub reggae, a recognized musical form since at least the late 1960s, was shaped by the use of cosmic reverb or space echo

Rush was one of the few mainstream hard rock bands in North America (if not the only one) left on the board to credibly embrace New Wave and music from around the globe. Moving Pictures not only solidified the band's desire to throw themselves headlong into a slimmed-down musical direction but also provided a vehicle to further navigate musical avenues they had only begun to explore a year earlier, such as we hear in the final song on the album, "Vital Signs."

"The world changed from the Punk Era that was pushing, pushing, pushing, and then it was gone," says drummer Jason Sutter (P!nk, Marilyn Manson, and Chris Cornell). "The Clash got popular and so did the Ramones, but that punky sound went into New Wave. The heavy hard rock of Led Zeppelin was over. The Genesis freak-out/Peter Gabriel era eventually led to the Phil Collins era and Abacab [1981]. The band switched gears. I think that definitely had something to do with the success of Rush."

Running the risk of scoring superficial points, we should note the band's public persona during the Moving Pictures time frame. Peart cut his hair, reverting to his appearance when he first joined Rush. Lifeson's long reddish/blond hair was chopped, perhaps in sympathy with the glam-inspired fashions of New Romantic and New Wave aesthetics. In concert, Lifeson even dons a crimson suit jacket and proverbial early 1980s skinny tie.

If appearances mean anything, then at least two-thirds of the band were desperately searching for an escape hatch from a false paradigm. Indeed. If we dress for the job we want, not the one we have, then Rush did not aspire to metal.

Not saddled with the same baggage as its British progressive rock counterparts, Moving Pictures is the sound of liberation. Largely setting aside what Rush biographer Steve Gett called the "Cecil B. DeMille proportioned epics" for a more condensed songwriting approach, Rush found themselves in a different headspace to create. The songs, on the whole, were shrinking in size, but the process of streamlining was quite liberating.

Through songwriting craft, production quality, and a bit of determination and perseverance, Moving Pictures became, quite simply, Rush's golden mean: the middle ground between excess and minimalism, progressive rock, hard rock, and synth/ techno rock. Yet it simultaneously skirts all of these confining categorizations. It's the alpha and omega of Rush and, by extension, of progressive hard rock.

If we deem all of these things to be true, how did Rush arrive at this point?

CHAPTER 2:

BIG SCREEN BEGINNINGS - THE CAMERA EYE, PART 1

(Scenes from the Rush Sound Track Reel)

Geddy Lee is silent as he stands at the center of the room. His eyes peer over the rounded rims of his specks, what some would call "John Lennon" glasses, and patiently waits for me to enter and for our interview to begin.

No matter how many interviews you do, you're always a little nervous when meeting people for the first time. You begin to question: How will the interview go? What is the person like? Have I got the correct line of questioning? How attentive am I, today, to ask follow-up? How aggressively do I press certain issues if I don't get the responses I was looking for?

Aside from all of that it's an odd feeling to meet someone like Geddy Lee, someone you'd seen perform numerous times onstage and in motion pictures or concert films, and then occupy the same space as he does. There's always this nagging feeling in the back of your mind about rock stars and pedestals and all of that crap. That is to say that it's all a bit surreal, as if you should not be sharing the frame with him.

Aside from all of that it's an odd feeling to meet someone like Geddy Lee, someone you'd seen perform numerous times onstage and in motion pictures or concert films, and then occupy the same space as he does. There's always this nagging feeling in the back of your mind about rock stars and pedestals and all of that crap. That is to say that it's all a bit surreal, as if you should not be sharing the frame with him.

But here we are: This is big screen. Or big-time reality. After a casual greeting, we're sitting at a hotel suite in New York City, where the loquacious Lee was promoting a record and speaking a bit about his career, Rush's next plans, and the band's possible future. He seems at ease, willing to talk, even eager. It's as if that significant gap between the guy in the stand and the rock star standing onstage shrunk.

When the interview was winding down, Lee easily transitioned from shop talk to a few personal topics: some of the music he'd enjoyed and even some of his pastimes.

I remember wearing my Yankees cap, a hat that for some reason I had always misplaced or lost for a time. Somehow, though, I managed to recover it, once even in a bad windstorm. I was glad I had it on that day.

Lee knew I was writing for a New York City daily newspaper and, I believe, had noted my hat before any talk of Major League Baseball arose. It seemed like a natural segue, so we talked Bronx Bombers, their chances for the pennant, and baseball in general, and I found that Lee was knowledgeable of New York sports, which was interesting for someone who made his home in Toronto.

"Mariano Rivera is untouchable in the postseason," Lee said.

We exchanged quips on the relief pitcher's stats, something about earned run averages, I believe, and spoke for a few more minutes. Funnily enough, it was one future Hall of Famer assessing another: Rivera earned a one-way ticket to Cooperstown, and Lee's band, Rush, made it to Cleveland, by hook or by crook.

The meeting was breaking up, and there was little milling around. Then it was over.

This initial meeting with Geddy Lee, all those years ago, are recalled in flashes. They've been strung together, and I've set the button to playback, as if a mini movie reel were spooling in my head: Geddy was and is obviously a rock star. But I was and continue to be struck by how down to earth he was.

Some of the thematic notes of the Rush song "Limelight" certainly resonate. We both had our jobs to do, I suppose, our roles to play: Geddy was promoting a record, and I was, myself, writing about it. But maybe for a brief moment, the veil had lifted, and I saw beyond the rock star. There was something real behind what Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock dubbed "Lee's clawing banshee how"

I'm sure Geddy can be charming when he wants to be, trying to win over the press with a relaxed smile, but he genuinely had an interest in talking baseball and one or two other topics. Most of all, I think, perhaps sensing I was a bit nervous to break that fourth wall and stand inside that "performance space," his attitude and approach set me at ease.

And I'll never forget him for that.

Part of what makes Moving Pictures a classic is the manner in which Rush and, specifically, lyricist/drummer Neil Peart treat the concept of fame and how it changes people. How did the band make sense of the world around them as they were becoming more popular than they had ever been? What did they think of their fans and the public at large?

These are deep, layered questions that cannot be easily answered. One of the ways to drill down to the core of the issue is to begin a kind of examination, a look at the artist's life in question.

The temptation is to search in their distant pasts for evidence, reasons for how and why they eventually created a record such as Rush's Moving Pictures. Some biographers might attempt to chronicle the early years of each band member to forge some symmetry between what these artists were as individuals, growing up in Canada, and what they'd become, in Rush's case, circa 1981, as blossoming rock stars.

Some may try to use Freud, Jung, or Lacan to inspect, psychoanalyze, and dissect their subjects from afar. But looking for biographical and psychological patterns can be tricky, especially since certain events or so-called signifiers can be easily misunderstood and improperly or disproportionally weighed as to their meaning in the overall story.

What I've done is present some meaningful facts about our subject matters in an attempt to understand a little bit about the formative years of Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, and Neil Peart and attempt to examine the music they wrote leading up to the album Moving Pictures. It's all in service to figuring out how Moving Pictures has endured, what makes it work.

Where appropriate, I've also included some personal reflections of my experiences with Rush, which you can find in certain select chapters under the subheadings "The Camera Eye."

The one question that has fueled me through the entire process was, why? Why did Rush fed the need to record an album containing music that they deemed to be cinematic and gather all of these conceptual pieces in one recording document? Maybe the reader and I can try to answer this burning query as we set out on this journey together.

Before heading off into the body of Rush's recorded output, we should start with a little bit of background and give a brief summary of how the band formed.

Alex Lifeson was born on August 27, 1953, aka Aleksandar ZivojinoviC, son of Yugoslavian Serbian parents (Alex's father spent time in a prison camp), left their home country, and emigrated to British Columbia after World War II. The family then moved to Toronto.

Alek was already playing viola but found he wanted something with a bit more oomph. The future Alex Lifeson made a pact with his mother that if he had good grades, he could get a guitar. His first, a steel-stringed Kent, a Japanese import, cost $25, a purchase for which his mother and father needed to secure a loan. The story goes that Alex found a way to amplify the acoustic by repurposing the stylus of his record turntable.

Lifeson told Guitar One magazine in 1996 that he'd listen to (or at the least heard) Eastern European music at home when he was young. But once the British Invasion hit the shores of North America, Lifeson had be seduced by the more modern sounds of Cream and the Yardbirds as well as the distortion-filled soundscapes of the Jimi Hendrix Experience and the West Coast/Bay Area psychedelic scene, including Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead. Later, of course, Lifeson was enamored of the guitar playing of the likes of Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin, Steve Howe of Yes, and Steve Hackett of Genesis.

Gary Lee Weinrib was born in Willowdale, Ontario, Canada, on July 29, 1953, son of Holocaust survivors Manya and Morris. The initial intent of Lee's parents was to settle in New York, but they continued to travel north instead.

"I was born in the suburbs of Toronto," Geddy Lee once told me, "[an] immigrant family that came over [from Poland] after the war. Largely Holocaust survivors. I grew up in an environment that is not exactly modern."

Lee's parents opened a retail store as a means of supporting the family. Lee's Polish mother, with her heavy Yiddish accent, pronounced "Gary" as "Geddy," and anyone who knew him referred to Lee by his new nickname. On Rockline Radio in October 1987, Geddy explained that it was his mother.

By age twelve, Geddy's father had died, and soon, after seeing a neighbor with a guitar, Geddy thought he'd like one himself. Taking money he'd earned from working with his mother in her retail store, Gary/Geddy bought his own six-string — an acoustic with palm trees painted on the face of it. Before long, music had seized his life.

"When I was thirteen, I became obsessed with music," Lee told me, believing that music chose him, not the other way around.

Alex and Geddy met in Fisherville Junior High School, in the Willowdale section of Toronto, and quickly became friends. They seemed to complement each other: Geddy a bit reserved and Alex more extroverted Each had a sense of humor and a love of music. They hit it off.

Alex would borrow Geddy Lee's amplifier, and the two began playing together at local coffee shops when the pair were in the eighth grade. At first, Geddy and Alex had not been playing together in a band at all. It was Alex and his neighborhood drummer friend John Rutsey, both in their early teens, who had teamed up and formed a band called the Projection. It was short lived, though, having lasted only a matter of months.

Myriad personnel changes throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s make it nearly impossible to follow the comings and goings of the band that would be Rush — that is, without a score card. But one highlight was a gig at a youth drop-in center in Willowdale called the Coff-In at St. Theodore of Canterbury Anglican Church. It was the first time Geddy, Alex, and Rutsey had played together. Their combined earnings for the gig was $10.

Pancer's deli was the next stop — to celebrate. And it was around this time that, legend has it, the name Rush was first used as the band moniker — a suggestion made by Rutsey's brother, Bill.

Ged, Alex, and Rutsey soon graduated to the Yorkville coffee shop scene, including the Upper Crust. They played music of the British Invasion: the Rolling Stones and the Animals as well as Van Morrison/Them, the Yardbirds, and Cream covers and other British blues-rock songs.

"I would pretend I was Eric Clapton, Geddy would pretend he was Jack Bruce, and we'd play 'Spoonful' for twenty minutes," Lifeson told Guitar One magazine in 1996.

Eventually, Lifeson had saved up enough money, working with his dad as a plumber's assistant, to buy a Gibson ES-335 and a Marshall amplifier along with a few effects pedals.

Again, personnel shifts marked a very messy period. Surprisingly, Geddy left the band, and by the summer of 1968, Jeff Jones was singing and playing bass. But he too left, and Geddy returned. Rush then added keyboardist/vocalist Lindy Young.

A name change to Hadrian was followed by Geddy leaving again in the spring of 1969. Some sources say he was fired, to be replaced by Joe Perna. Undeterred, Geddy formed the blues band Ogilvie (which later changed their name to Judd). Lindy Young exited Hadrian (formerly Rush) and joined Geddy in Judd, which had been booking gigs with the assistance of young hype man Ray Danniels.

Then a strange twist of fate occurred. Joe Perna wasn't meeting expectations, and Rutsey and Lifeson decided to call it quits, for the time being, anyway. Perhaps because Rutsey and Lifeson realized the error of their ways or perhaps because Judd, keeping active throughout the summer of 1969, had broken up, Lifeson and Rutsey re-recruited Geddy, and he (and the name Rush) was reinstated.

Lee was back, Lindy was off to college, and one of the greatest power trios in rock history had just solidified its lineup. Immediately, the band got to work. Funnily enough, Lee would eventually marry Lindy's sister, Nancy.

John and Alex penned a song tided "Losing Again," which became one of the first (if not the first) tune the band wrote together. All three would contribute pieces or pieces of ideas, bring them to the band, and develop them. Around this time, Geddy had been working on "In the Mood," which was virtually completed when the bassist/vocalist brought it to the guys.

By the early 1970s, other originals, such as "Morning Star," "Love Light," "Garden Road," and "Child Reborn," among others, were composed, some heavier and more complex than others.

In the meantime, Rush continued to play a mixture of originals and covers, including Robert Johnson's "Crossroad Blues" (made famous by Cream via its super-charged revamp "Crossroads"), the Bonnie Dobson/Tim Rose folk classic "Morning Dew," and music by Jeff Beck, Buffalo Springfield, David Bowie, Jimi Hendrix, the Yardbirds, the Rolling Stones, Traffic, and Eric Clapton, among others.

"Years before I joined Wireless, I was playing in a band called Truck, from southern Ontario," says drummer/vocalist Marty Morin, whose former band, Wireless, would be produced by Geddy Lee in the late 1970s. "A number of times Rush would open for us. I remember when John Rutsey was in the band and we would do these summertime shows at, what we call up here in Canada, pavilions. Even back then Rush were a little bit different. They insisted on using their own lights. It may have been just some floodlights screwed to a two-by-four, but they insisted they had to have their lights. I remember Alex Lifeson painting glitter nail polish on his fret hand. They were doing something just a little extra."

In early 1971, someone named Mitch Bossi was added as a second guitarist, but he left after a few months. Despite these comings and goings, the band continued packing crowds in the bars of Toronto, including at a venue called the Gasworks on Yonge Street. And why not? The drinking age in Toronto had dropped from twenty-one to eighteen years of age, significantly impacting who could get buzzed and, more important, who could attend the band's shows.

Although they'd face challenges over the next two years, including witnessing a dip in support and being tossed from a venue for volume, by 1973, Rush had entered Eastern Sound Studio and recorded their first single, "Not Fade Away" (written by Norman Petty and Charles Hardin, aka Buddy Holly), and an original, "You Can't Fight It," composed by Geddy and John. David Stock, a Brit who had worked with Ray Danniels and Vic Wilson's SRO Management company, was the recording engineer.

"Not Fade Away" is a raunchy raver, simmering with crunchy guitars, echo-enhanced vocals, and a Bo Diddley — esque hambone/West African beat. At just under three minutes, "You Can't Fight It" further slips into heavy riff rock, impressing with the briefest of drum solos. Its hypnotic tempo falls somewhere between northeastern punk and British blues rock. It's not difficult to hear why so many observers chose to compare Rush to Led Zeppelin and Uriah Heep.

At the time, Rush had written and performed two other songs, "Fancy Dancer" and "Garden Road," largely blues-rock numbers that, to my knowledge, were not recorded at Eastern Sound.

Truth be told, even prior to the single they'd cut at Eastern Sound, Rush was attempting to shop a semiprofessional demo they'd made at the Sound Horn at Rochdale College. This was the first of the band's unfortunate run of luck with courting Canadian record labels.

Manager Ray Danniels, who had been promoting the band since the early days of 1969 and had already established his own agency, Music Shoppe, tried in vain to score a record deal for Rush in Canada. Due to the lack of response, Danniels and his business partner, Vic Wilson, formed Moon Records and released the band's single with an eye toward recorded a full-length LP one day. Hundreds of copies were pressed.

It was settled: Rush would record a full-length record and make a run at greatness. After one of their numerous gigs around town, the band assembled at Eastern Sound in Toronto and hammered out most of the record in nearly eight hours in the wee hours of the morning, largely to keep the budget costs down.

Unhappy with the sound quality of what they'd tracked at Eastern, they moved on over to Terry Brown's Toronto Sound Studio in the fall of 1973 to record new songs and rerecord others.

Brown had been an engineer in England, his native country, before arriving at the shores of Canada in 1969, just prior to the great recording and creative boom in Toronto and in Canada in general. With business partner Doug Riley, Brown opened Toronto Sound in 1969, and a Toronto recording scene was born.

After a couple of days' work, Rush recorded what would become the debut's stunning opener, "Finding My Way," and the rest of the tracks, including redoing guitar tracks. Mixing and remixing occurred during this time, too.

"They had been recording during the graveyard shift, mixing and recording some extra tracks," Terry Brown once told me in an interview I conducted. "Vic Wilson [partner in Rush management company] called me and said, 'Can you look after the boys?' Do something with them.'"

The record was completed in late 1973, and thousands of pressings were done in March 1974. The cover image by Paul Weldon popped, like an action scene from a comic book. Weldon, an Andy Warhol acolyte and an actual comic-book letterist, fathered what has gone on to become one of the most iconic debut covers in rock history.

In an early Rush press release promoting the band's debut, Lee indicated that there was some interest from Canadian labels but that they'd decided to release their eight-song debut on their own independent label, Moon Records, a division of SRO Productions. Danniels has gone on record as saying the production of the record cost himself and Vic Wilson a combined $9,000 — not insignificant for a small operation like SRO catering to a relatively unknown band in the mid-1970s.

Donna Halper, music director at Cleveland's kingmaker radio station WMMS, originally from Boston, was an admitted fan of Canadian rock bands. When friend Bob Roper at A&M Records in Canada gave Halper a copy of the Rush debut, Halper handed the record to DJ Denny Sanders to ask his advice about playing any of the songs on air. Sanders liked the record and agreed that this band Rush had something and began spinning "Working Man."

"Finding My Way," "Here Again," and "In the Mood" soon followed, receiving their own public airing on WMMS; the requests kept pouring in.

As the story goes, Halper solicited Ray Danniels and Vic Wilson to ship copies of the Rush debut to a Cleveland-area record store, Record Revolution, owned by Peter Schliewen, known for its imports. Within weeks, hundreds of people bought it. Soon, that number jumped to thousands in and around Cleveland, not including the 5,000 LPs that had already sold in Canada on Moon.

Although Halper's position in Rush lore is well established, we should note that inside the borders of Rush's native Canada, there were early champions of the band, such as DJ Don Shafer ("The Voice") and David Marsden formerly of CHUM-FM in Toronto.

"Don and I have been supporters of Rush since the mid-1970s," says Marsden, who you can find on Internet radio at www.nythespirit.com. "I was at CHUM-FM at the time, when the first album came out and I started playing it before anyone else in North America had been playing it — contrary to the popular story that's out there."

Halper was Rush's connection in the prized United States, however, and Halper knew Mercury Records promo/artists and repertoire (A&R) man Cliff Burnstein, who had heard the band's debut and was impressed with the sound and power of the music. Burnstein, who would later comanage heavyweights such as Metallica (who were themselves Rush fans), urged the label and its director, Irwin Steinberg, to court the band. Mercury had already signed Bachman-Turner Overdrive, another hard-driving Canadian band, so looking to the Great White North was not something Mercury was averse to.

However, there was some (if minimal) interest at other labels, including Casablanca and Columbia. Producer Tom Werman liked Rush, and there was some discussion about signing the band to the Epic record label, but he could not convince the brass to do so. It was Mercury that scored the deal and hammered out a two-record contract worth a reported U.S.$200,000.

Founded in Chicago in the late 1940s, Mercury nurtured a roster of rhythm and blues, blues, jazz, folk, and soul artists, ranging from Bill Eckstine and the Platters to Sarah Vaughan, Frankie Laine, Josh White, Josephine Baker, Buddy Rich, Patti Page, Dinah Washington, and Big Bill Broonzy. This is to say nothing of the symphonic and classical releases the parent label issued through its imprints in the 1950s and 1960s. And in the decade prior to the release of Moving Pictures, Mercury had quite a diversified portfolio: Rod Stewart, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, the New York Dolls, the Ohio Players, Uriah Heep, and others.

From the mid-1970s though the mid-1980s, Mercury U.S. and Canada did not shy away from signing and distributing progressive, arty pop, and avant-garde artists, such as Aussie prog band Sebastian Hardie (specifically their Four Movements LP from 1975), lOcc's classic 1970s catalog, Cleveland art punkers Pere Ubu, and one of the more eclectic bands to emerge from England's musical underground, Jade Warrior.

Interestingly, not long after (or virtually timed with) the arrival of Moving Pictures, Mercury pursued two strains of rock prevalent in Rush's sound circa 1981: New Wave and hard rock. Suddenly, Soft Cell, Tears for Fears, Big Country, Bon Jovi, and Kiss made the cut, and the success of Def Leppard seemed to mirror Rush's own rise to prominence from the late 1970s through the early 1980s.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves.

Moving Pictures: How Rush Created Progressive Hard Rock's Greatest Record