|

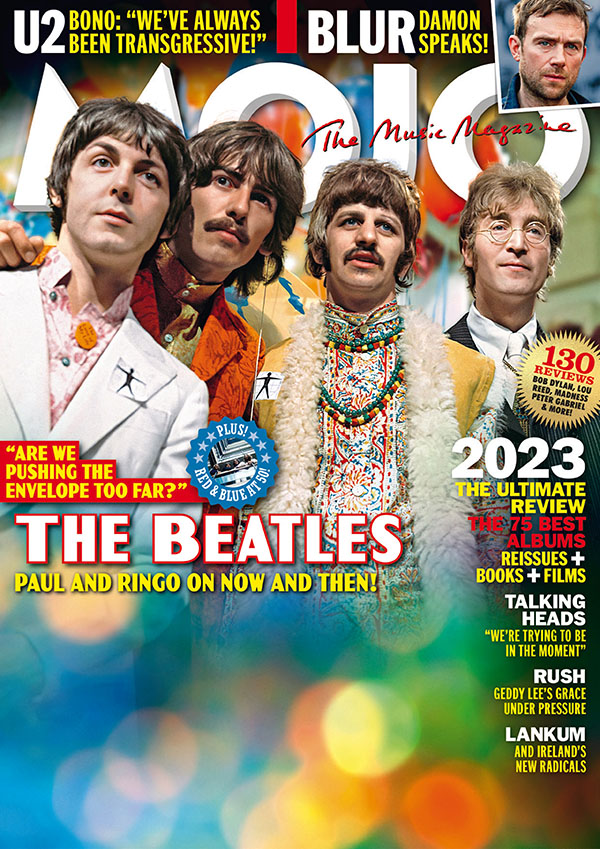

Grace Under Pressure The Mojo Magazine Interview MOJO Magazine January 2024 Interview by JAMES McNAIR • Portrait by RICHARD SIBBALD |

The high voice and low moments of Rush’s bass ace, dealing with the passing of Neil Peart and the end of his band:

“I was actually quite depressed.”

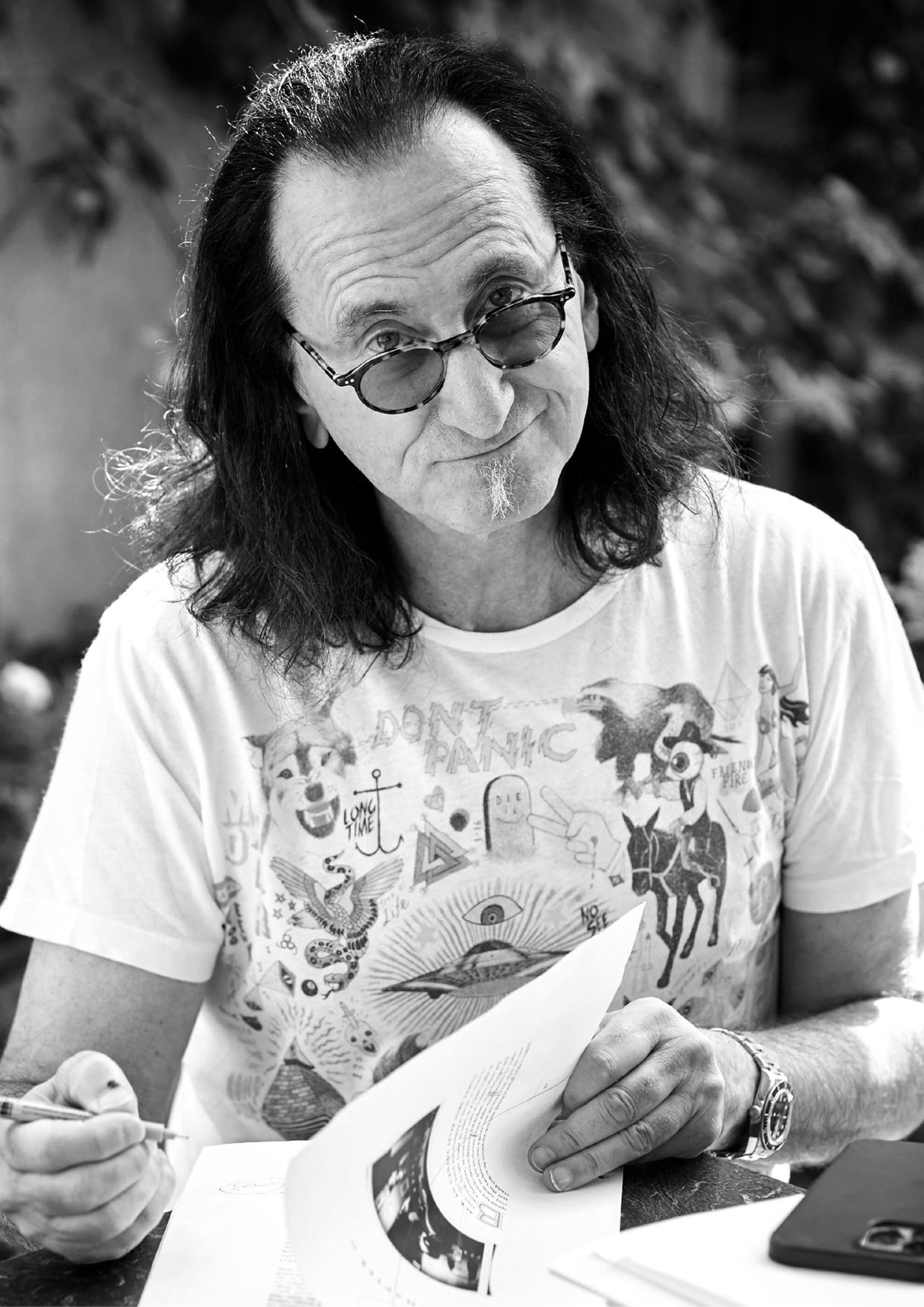

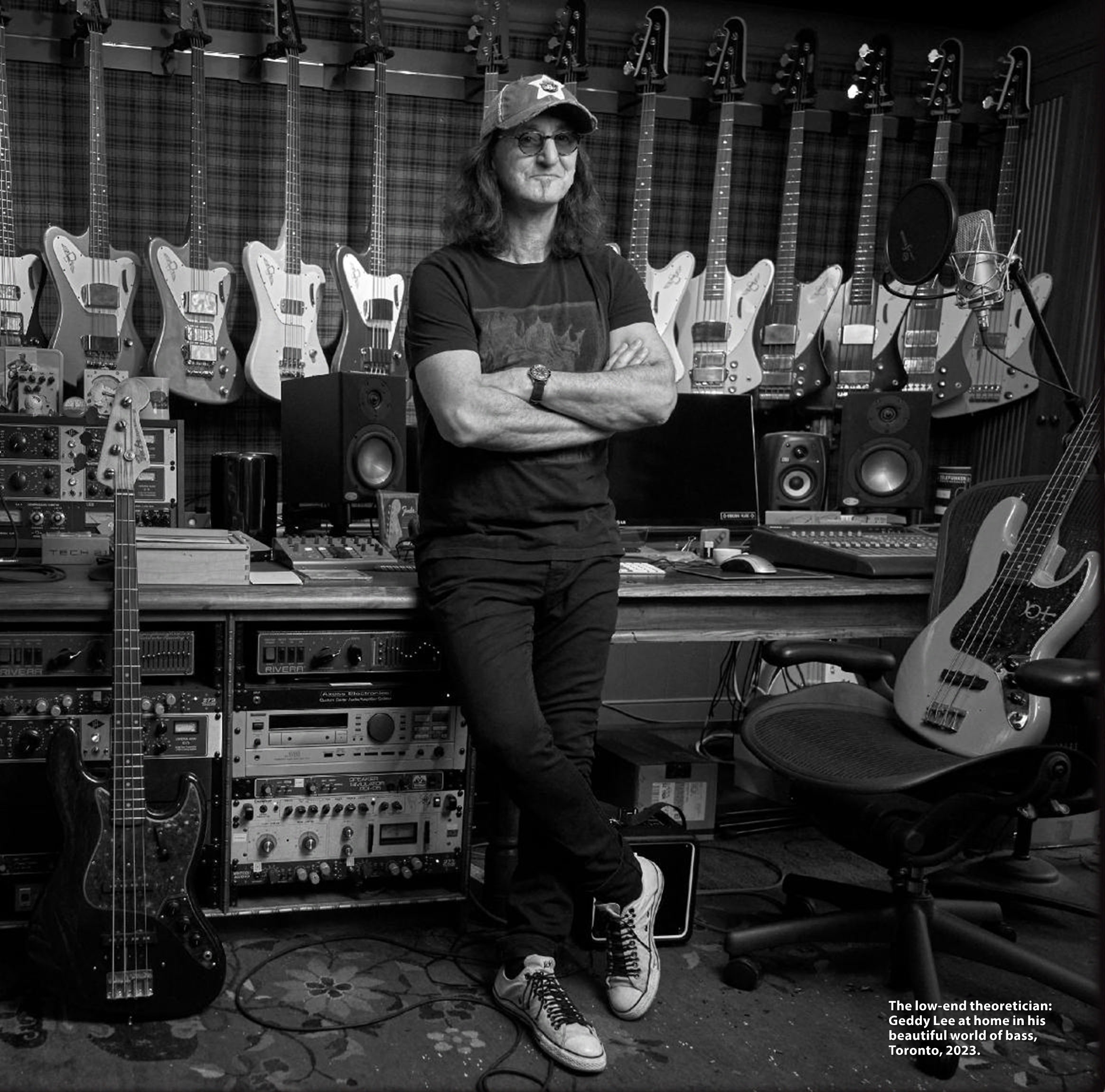

Sorry – One moment…” When the doorbell sounds at his Toronto home, Geddy Lee briefly disappears, leaving MOJO with his well-stocked library and a painting of his Norwich terriers. Our encounter has been sparked by Lee’s new memoir My Effin’ Life, a work whose zany title helps offset some sobering content. The book is funny, but also moving, occasionally harrowing. The dark sunglasses and low-visored baseball cap Lee wears today are not accoutrements of vanity, MOJO surmises; rather they offer protection during a free-ranging, sometimes emotionally raw conversation which sees Lee choke up more than once.

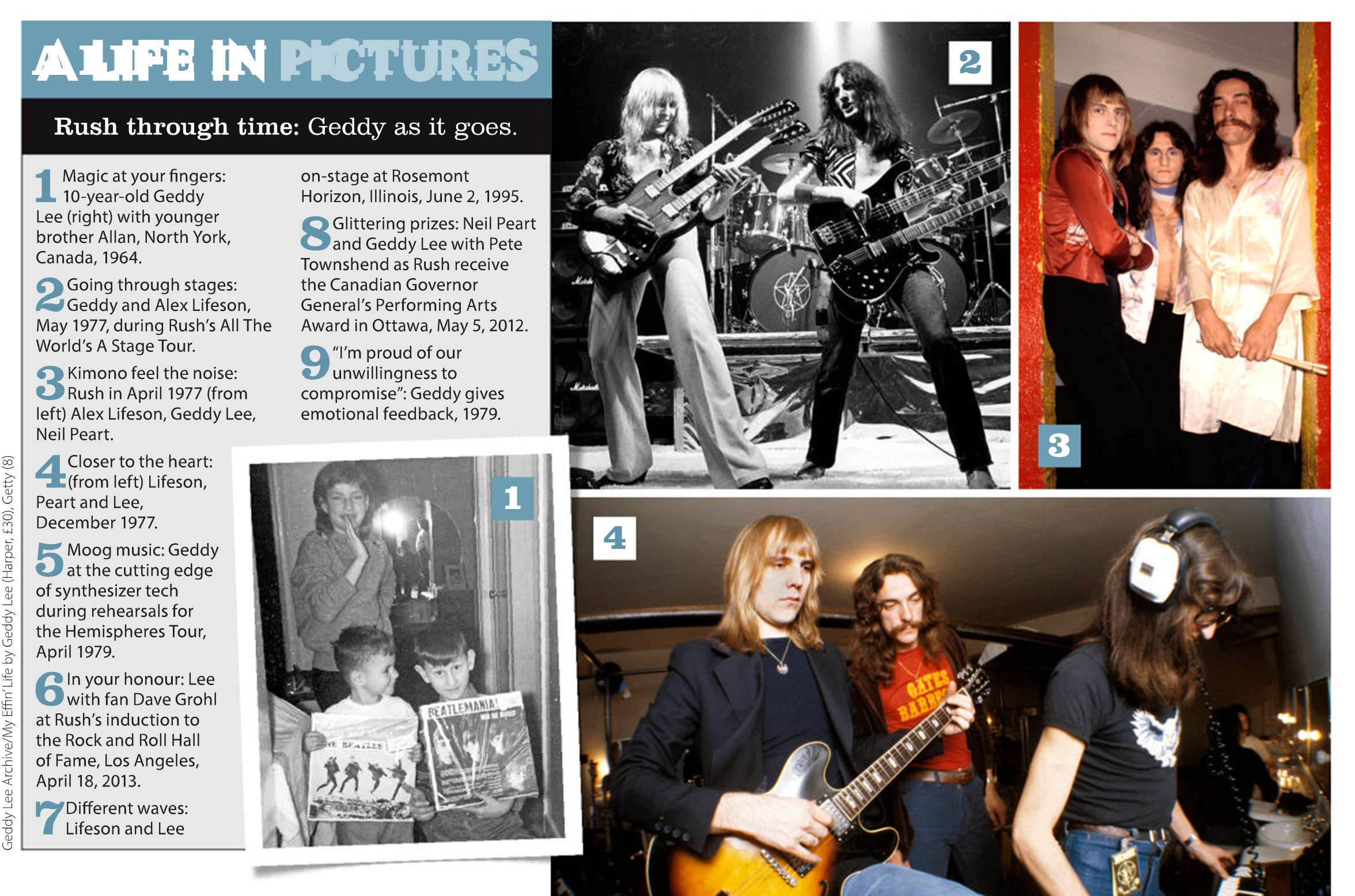

Born Gershon Eliezer Weinrib, Rush’s singer and bassist was named after his maternal grandfather, a Polish Jew murdered in the Holocaust. Having survived Auschwitz, Dachau and Bergen-Belsen, his parents Moshe and Malka emigrated to Canada, where Lee was born in 1953, soon befriending another scion of Eastern European immigrants, Aleksandar Živojinović, AKA future Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson. With bookish, lyric-writing drummer Neil Peart joining for Rush’s second LP, 1975’s Fly By Night, this close-knit, virtuosic power trio bonded around a love of goofball humour and Brit invaders Led Zeppelin, The Who and Cream.

Active from 1968 to 2018, Rush have sold close to 50 million albums. They morphed from Zeppelin wannabes to kimono-wearing prog rock gods, eventually channelling UK new wave acts The Police and Ultravox. Lee’s powerful, high-pitched voice alienated some listeners, and drew hurtful jibes. Much of the mainstream music press shunned Rush for decades, thinking them geeky (right), pompous (wrong), and dully abstemious (very wrong).

The trio’s ever-expanding fan-base remained fiercely loyal, and from the noughties onwards, Rush enjoyed a cultural and critical renaissance. Banger Films’ intimate 2010 profile Rush: Beyond The Lighted Stage captured the loveable, beating heart of Rush and their enduring three-way bromance, while cameos in South Park and US comedy film I Love You, Man broadened their appeal. Soon Rush did the big US talk shows and found themselves inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by superfans Dave Grohl and Taylor Hawkins. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada even named a star after Lee: Asteroid 12272 GeddyLee. The geeks had inherited the earth.

Tragedy derailed them; nothing broke their bond. Rush were inactive and their future uncertain for four years when Peart lost his 19-year-old daughter Selena in a car crash, then wife Jackie to cancer. Courageously, they returned with 2002’s Vapor Trails, then 2008’s final, core values-reasserting Clockwork Angels, bowing out with their R40 North American Tour in 2015. Prior to Peart’s death from brain cancer in January 2020, Lee and Lifeson had kept his illness a secret for three years, as per his wishes. Lee’s memoir relives that dark chapter, and much more besides. “There were growing pains involved,” he says ruefully.

Tragedy derailed them; nothing broke their bond. Rush were inactive and their future uncertain for four years when Peart lost his 19-year-old daughter Selena in a car crash, then wife Jackie to cancer. Courageously, they returned with 2002’s Vapor Trails, then 2008’s final, core values-reasserting Clockwork Angels, bowing out with their R40 North American Tour in 2015. Prior to Peart’s death from brain cancer in January 2020, Lee and Lifeson had kept his illness a secret for three years, as per his wishes. Lee’s memoir relives that dark chapter, and much more besides. “There were growing pains involved,” he says ruefully.

My Effin’ Life is a bit different from your previous book, Geddy Lee’s Big Beautiful Book Of Bass…

Just a tad. My publishers were leaning on me for a memoir, but the idea of wrapping up my life in print seemed odd and premature. Then the pandemic happened after some very difficult years of me dealing with Neil’s illness and ultimate passing, and I was sat in lockdown in Toronto with the realisation that a huge part of my life was over. On top of that, my mum, who I was very close with, was suffering from dementia, and would die aged 95. Her struggles affected me deeply, and made me question how long my own grey cells would be in working order, so I got it all down.

Was that cathartic? You’d been in Rush for over 50 years…

Well, I was actually quite depressed because of Neil’s struggles and what they had represented. Back in 2014, when Neil first told us he wanted to retire, it was very difficult for me. I didn’t react like the friend I thought I was. I was frustrated, a little resentful. I understood all the reasons why he felt he had to say goodbye and spend time with his new family [Peart married second wife Carrie Nuttall in 2001; their daughter Olivia was born in 2009], but I had to do some soul searching. Then when Neil got brain cancer of course I felt like a complete heel, and my resentment dissipated immediately. But I still needed help with various feelings.

Professional help?

Yes, I started talking to a therapist. I’ve gone down that road a couple of times and find it helpful. And the whole memoir endeavour seemed to be part and parcel of all that. There were some unresolved issues from my childhood – the passing of my father, for example. So it was cathartic for me to review those things. But before I knew it I had over 1,200 pages of manuscript, which should not be imposed upon any human being. My editors trimmed it to a more reasonable 500 pages or so.

What music first blew you away?

Oh, Pretty Woman by Roy Orbison was one of the first songs where I was kind of awestruck. That guitar riff was haunting to me, and it was the first single I ever bought. Then it was For Your Love by The Yardbirds. I was also a big fan of The Supremes.

Your bass playing influences include James

Jamerson as well as Paul McCartney and Yes’s Chris Squire. Has your funkiness been overlooked? (Laughs) White Canadians aren’t funky, dude! But I’d hear these fantastic bass lines on Motown records and years later I discovered many of them were by James Jamerson. Toronto wasn’t that far from Detroit – that Motown influence definitely seeped in. Of course, what I chose to play was blues-rock. But I didn’t really like ‘real’ blues – I liked the way you Brits did it and sent it back across the ocean.

Your closest childhood friends were a certain Aleksandar Živojinović, and Oscar Peterson’s son Oscar. Outsiders bonding?

Yes. The minute Alex and I sat together at school we started laughing, and we haven’t stopped almost 60 years later, which is a fucking rare thing in this world. Oscar was a big loveable guy, always up for a beer or 10. Like Alex and I, he had this demented sense of humour. Oscar and I never once talked about him being black and me being Jewish, but we were very aware of being outsiders.

It was only after your father’s death that you learned he had been a musician, and that your mum had insisted he leave his balalaika behind after their liberation from the camps…

It was only after your father’s death that you learned he had been a musician, and that your mum had insisted he leave his balalaika behind after their liberation from the camps…

When my aunt told me that, I thought, She’s just making this shit up. My dad died when I was 12, but he never talked about music to me. My parents had survived the Holocaust and were trying to build new lives in Canada, so I guess he had bigger fish to fry. When I eventually spoke to my mum about it she was very sheepish, though.

Alex has spoken of seeing your mum’s concentration camp number on her arm when he was a kid – the shock of that. Was the weight of what your family had experienced a constant presence?

Every child of Holocaust survivors will tell you a different story, but I was fortunate in that my mother wasn’t afraid to talk about it. It literally gave me nightmares when she did talk about it, but I felt I understood what they had gone through. It didn’t make me a kinder teenager, though. I was still desperate to get out of the house and join the circus. It was only years later that I was able to look at her life much more sympathetically and heal any rift between us in those difficult teenage years.

Rush’s self-titled 1974 debut was heavily influenced by Led Zeppelin. You saw them in Canada as a kid, right?

It was life-changing. [Rush’s first drummer] John Rutsey had seen them on their very first trip to Toronto at this little club called the Rockpile. As soon as the first Zeppelin LP dropped we all bought it and thought, What is this? It had a kinda Humble Pie vibe, but it was broader and the brushstrokes were bolder. We were in ecstasy, jabbering about them non-stop. That fall they came back to Toronto and John, Alex and myself sat in the second row. I didn’t think they were beings who walked – they floated onto the stage like gods.

From the outset, you and John Rutsey wanted different things?

John was a real rocker. Into glam and the glam image, and a drummer in the spirit of [Free’s] Simon Kirke. Alex and I soon realised our musical differences with John could not be overcome, plus John had legitimate health fears related to his diabetes and it was clear that touring America wasn’t on the cards for him. We were hungry to expand our sound, and he was not. So when Neil walked in to audition that day and blew us away, we knew we had found our fellow traveller.

All three of you were virtuosos…

Alex was always incredibly talented and spontaneously creative. Those big fat Serbian fingers of his meant his guitar strings didn’t stand a chance! And they gave him a tone which was not like that of his heroes. Then Neil came in and had a catalytic effect on our creative corpuscles. Neil lifted me up as a bass player. I’d like to think I pushed him too.

Yet your third LP, Caress Of Steel, bombed. In your book you tell of playing it to Kiss’s Paul Stanley and “the guy who sang Strutter every night” looking perplexed.

Right (laughs). I can’t look at Caress Of Steel as successful, but we had to try a concept record sooner or later. When you’re contracted to release two albums a year, you record what you write. And as naive as parts of that record were, some of it is kinda cool and some of it is kinda funny.

Then came 1976’s 2112, the record where you defined your early sound.

Our confidence had been shaken by the response to Caress Of Steel, but we knew we wanted to make a great record or die trying. We didn’t recognise 2112 as a quantum leap forward when we were making it, though. We didn’t have the objectivity to see why it succeeded and Caress… failed. But clearly, 2112 was more passionate and cohesive, and had better songs. Career-wise, it saved our bacon.

In 1978, a snarky NME piece by Barry Miles accused Rush – and Neil in particular – of “proto fascism”, and pilloried Neil’s admiration for Russian-American writer, Ayn Rand.

It’s amazing how long that mud stuck. Part of the way we used Rand’s inspiration was defiantly anti-totalitarianism, as played out in the sci-fi plot of 2112. And, fairly obviously, we were never fascists. Thatcherism was rising in Britain. The left were understandably freaked out, and I didn’t blame [Miles] for having the belief system he had. But to suggest that 2112 was suckering kids into a right-wing mantra with fascistic overtones was wrong-headed and irresponsible.

Rand arguably aged badly after neo-liberal liberalism’s merging with neo-conservatism in the 2000s. Do you regret the connection with her?

Many of the American libertarian dudes that I have very little respect for are Rand devotees, it’s true. But I don’t regret the connection, no, because I was a 23-year-old kid, and Rand’s writing in The Fountainhead really stimulated my brainwaves. Also, no one is the finished product at 23, and we should all reserve the right to disagree with our younger selves.

How did your hard rock peers view Rush? As eccentrics?

They didn’t necessarily like our music, but we always got technical respect, even if they weren’t going to buy our records and study them. Musically, we were more of an influence on the generation that came after us. Bands like Primus, and the whole Seattle grunge scene. With very few exceptions, we got on well with bands we toured with, especially if they liked a drink. Nazareth drunk us under the table, though!

The received wisdom about Rush was that they weren’t druggy. But you dropped purple Owsley microdots in 1969 and got into cocaine in the ’80s and ’90s. How come we didn’t know?

The received wisdom about Rush was that they weren’t druggy. But you dropped purple Owsley microdots in 1969 and got into cocaine in the ’80s and ’90s. How come we didn’t know?

Well it wasn’t like Zeppelin. People weren’t writing about what happened on the tour bus, so that saved us from prying eyes. We could fuck ourselves up in private.

The book explains why you quit cocaine.

Well, firstly, our touring schedule in those years was insane. We once did 23 one-nighters in a row, all in different cities. Our youthful energy was finite and at some point the cocaine was actually useful. And fun. My buddies would meet me stage-left during the drum solo and we’d do some lines. Then there was a night in Texas where a buddy and I were trying to score coke, and, terribly, we used some fans to acquire some. I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror the next day. I could hear my mother’s voice: “Nice Jewish boys don’t drink beer.” Nice Jewish boys don’t exploit their fans to score coke, either.

Neil’s views on fame and fans were spelt out on Limelight on Moving Pictures [1981]: “I can’t pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend.” Was there an agreement: you write the lyrics, we’ll do the meet and greets?

Yeah. Neil hated all that. In the early days when our meet and greets were after the show, Neil was already gone, cycling to the next gig.

Remarkably, his lyrics for Red Sector A [from 1984’s Grace Under Pressure] were partly a portrayal of your family’s experiences in the concentration camps.

Yes. He and I had had a conversation about the day my mum was liberated from Bergen-Belsen. I told Neil how shocked my mum had been when she realised that their world had not been destroyed. She had assumed everyone was dead, that there was no hope. That affected Neil deeply, and I was very appreciative of those lyrics. I could sing them with real heart.

You haven’t had many outsider collaborators, but Aimee Mann sang on Time Stand Still, from 1987’s Hold Your Fire.

She was amazing. We were all totally mesmerised, complete goofballs around her. She sang beautifully and trusted us with her voice.

Those late-’80s records were more technology-orientated. What did peers make of Rush hiring Andy Richards [Propaganda, Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Grace Jones] on additional synths?

We weren’t ones for discussing our intentions with management, the record company or anyone else. If we were going to make a foolish mistake, that was on us. Peter Collins [producer of 1985’s Power Windows] said, “We’ll work in England – I know some musicians there who’ll bring us right up to date.” We agreed without realising quite what would happen. Andy Richards brought tons of kit with him: the Andy Richards show. Alex was freaked out, but I was intrigued.

You acknowledged the influence of various British new wave bands. What did you want a piece of?

With Ultravox, say, there was a rich musicality there. We were a riffy hard rock band who wanted to learn more about song structure and write better melodies. We wanted to be more compelling and didn’t want to stand still.

But the reduced role for guitar alienated Alex: “I’ll just play what you want me to play,” he said, echoing what George Harrison said to Paul McCartney. Was that the closest Rush came to splitting?

Probably. But I was blind to it. Alex didn’t express his frustrations to me overtly, and I was too up my own ass to hear him anyway. I was in love with what we were doing and feverishly learning from this process. And Neil was always for change, always for experimenting. Alex, too – he’s one of the great guitar experimenters of all time. But he felt his territory being encroached upon and understandably felt unhappy.

The book is good on how the band took over your lives. You talk about a “dereliction of duty to my wife and son”. How did you mend that?

Nancy and I worked hard to rebuild our relationship. Through all our difficulties, we loved our son Jules, who was being victimised by our estrangement. We did therapy and started telling each other how we felt about pretty much every fucking thing (laughs). You realise that a successful relationship without an open dialogue is a pipe dream – it’s not going to happen.

The pages where you write about Neil losing his daughter are very moving, Neil falling into your arms and saying “You understand!”

It was a deeply terrible loss to witness, and very hard for Alex and I to know what our roles were. We’d visit Neil in London, where he and Jackie were holed up, running from the awful event, and I’d bring in the clown, Alex, who was somehow able to make them laugh. They needed to hear about lives that had not been destroyed.

Then 10 months later Neil lost Jackie to cancer. He said her broken heart was one of the causes.

It was just unbelievable what was being thrown at this guy.

While Rush was on hold, you went to Morocco with Nancy, where you had a chance encounter with Robert Plant…

Yes. He was amazing. Nancy and I arrived at the hotel sweating. We’d been biking with a group of strangers in the Atlas Mountains, hoping none of these lawyers who had a bit of dough were Rush fans. I’m putting the key in our door and there’s this guy in the corridor who looks a lot like Robert Plant. Anyway, about half an hour later he introduced himself at dinner and his advice was so heartfelt. Sometimes your heroes are worth meeting. Later, when Page & Plant were playing Toronto, he invited Alex and I along. I told Robert I wasn’t ready to be out in public, and he said, “You know, sooner or later you guys will have to get back to your lives.” So we went to the show and had a ball.

Meanwhile, Neil was on a 55,000-mile solo motorcycle journey from northern Canada to Belize and back, trying to re-build his “little baby soul”. You must have had your doubts about how he might fare?

You couldn’t stop him. If Neil wanted to do something, he could impose his will, but you accepted that Neil in order to get all the other great things he had to offer. We were deeply worried, but we had a little network of friends keeping watch, mapping his whereabouts: “He was here a couple of days ago, and he seemed OK.”

Then Neil met Carrie Nuttall who, in less than a year, would become his second wife. She was clearly a catalyst in Rush regrouping in 2001 after four years away…

We were so happy for him (chokes up). He was very damaged by his losses, but she opened the skies for him, and there was a new positivity that made us feel we didn’t have to worry. He quit smoking. OK, that didn’t last (laughs), but Neil was in the best shape of his life. We still didn’t know if Rush had a future, then he e-mailed saying it was time for him to seek “gainful employment”.

What did it take for Rush to get back on track for 2002’s Vapor Trails?

It was a year of our lives. At first, we sounded like a bad Rush covers band. We took over a small studio in Toronto and bedded down there. Neil again became the incredible drummer he always was and his lyrics became a different, even more eloquent story. There was a lot of back and forth required between us for me to sing them, but it worked out.

Did you have a new perspective?

We felt like we had nothing to lose any more. We’d been given a second chance and that relaxed us. Even through the darkest times, the bedrock of our friendship was always oddball humour and it started evidencing itself in the bizarre rear-screen projection films we were making for the live shows [which included Lee as kilted Scotsman ‘Harry Satchel’], and in the fake chicken rotisserie ovens I had on-stage instead of amp stacks.

The group’s renaissance and wider acceptance really grew from 2010 onwards, partly because of Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn’s 2010 documentary Rush: Beyond The Lighted Stage…

Yes, I think our female fanbase increased a lot. Women could see that we were all family guys, and they liked that.

But you had these health issues: Alex’s arthritis and Neil’s tendonitis. Given he now had a young daughter, Olivia, was Neil’s retirement inevitable?

Probably. Neil was an uncompromising artist in the truest sense. So, not only was he torn every time he left his new family to tour, he also had this lingering fear of letting the side down. Few things scared Neil more than no longer being able to play as well as he could.

When Neil told you about his brain cancer, how did you and Alex cope with the stress of keeping that secret?

We didn’t cope. It caused Alex and I serious stress. We got very good at lying. Friends would ask point blank: “I’ve heard weird things about Neil – is he OK?” You love these people who are asking out of genuine concern, but you’ve made this unequivocal decision. We had to remain loyal to Neil’s wishes.

What are your fondest memories of your final visits with Neil?

It was always better when Alex and I went to LA together. I’d embarrass Alex and Neil would laugh. We had a few good dinners, a couple of good lunches. We’d sit with him in his ‘Bubba Cave’, this office-slash-garage where he had his prized car collection: his Silver Shadows, his Lamborghinis and Aston Martins. It was his inner sanctum and the three of us would go at it with a few fingers of Macallan.

How was he in spirit?

Often as if there was nothing wrong. And other times not so much. But he did not want to talk about his fucking illness – he would brush it away: “Mustn’t grumble!” So three-and-a-half years like that. Sometimes we’d meet other musician friends of his there. Stuart Copeland, for example.

Looking back, what are you most proud of? Rush’s music? Or the integrity with which you conducted yourselves?

I have a hard time thinking of myself as someone with integrity. It’s not for me to say. I think I’m most proud of our unwillingness to compromise. It was not always in our best interests, but we couldn’t help it. I loved that about us.

Did you have to clear a lot of stuff in the book with Alex?

Well, for the first time, I asked him why I briefly got kicked out of the band in 1968, and about why he allowed that to happen. He was very sheepish and did a lot of looking down (laughs). Then when I finished the book, the first person I sent it to was Alex. And he wrote me (suddenly overcome with emotion)… the most beautiful letter.

2024 is the 50th anniversary of Rush’s debut album. Might you and Alex perform together?

I honestly don’t know. For a guy who’s supposed to be retired I’ve never been busier in my effin’ life. After my book tour, Alex and I are going away on holiday together. I’m sure we’ll talk more about it then.

-| Click HERE for more Rush Biographies and Articles |-