This book is dedicated with love to the amazing N.Y., without whose steadfast encouragement

and extreme level of nerd tolerance it would not have been possible for me to go

down, down, down the rabbit hole once again . . .

Click Any Image to Enlarge

CONTENTS

Backword by Alex Lifeson

Introduction:

Falling Down the Rabbit Hole

Chapter One:

Fender

Fender Precision Bass

Interview with Jeff Tweedy

Fender Jazz Bass

Interview with Alan Rogan

Fender Bass: Outliers and Oddities

Interview with John Paul Jones

Chapter Two:

Gibson and Epiphone

A Brief History of Gibson

Gibson Short Scale Solid Body

Epiphone Short Scale Solid Body

Gibson-Epiphone Short Scale Hollow Body

Interview with Adam Clayton

Gibson Thunderbird

Gibson Thunderbird Reverse

Gibson Thunderbird Non-Reverse

Interview with Ken Collins

Chapter Three:

Rickenbacker

Rickenbacker Solid Body

Rickenbacker Hollow Body

Interview with Robert Trujillo

Chapter Four:

Höfner

Höfner “Violin” Bass

Höfner Archtop Bass

Höfner Solid Body

Chapter Five:

Ampeg

Interview with Bill Wyman

Chapter Six:

Around the World in 80 Basses

(More or Less)

Interview with Les Claypool

Interview with Bob Daisley

Chapter Seven:

My Favorite Headaches:

Stage and Recording Gear, 1968–2018

A Kaleidoscope of Bassy Moments (and Other Historical Stuff)

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

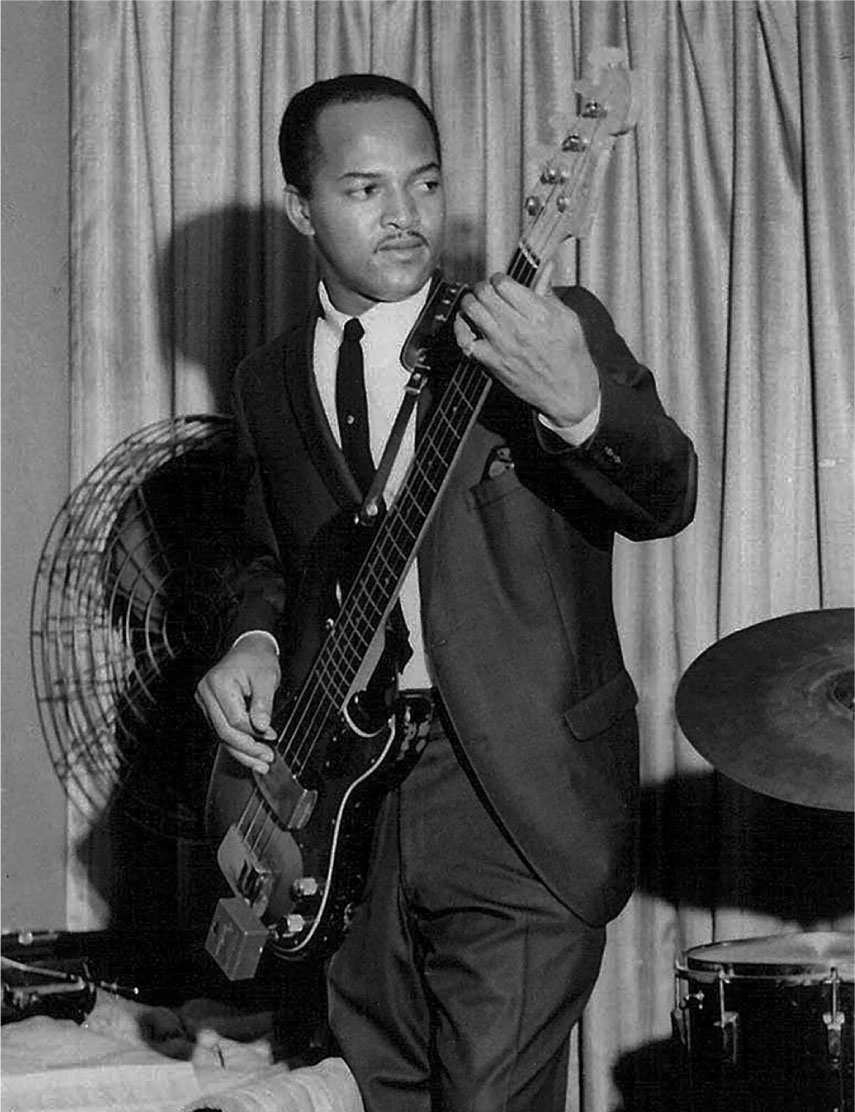

Terry Foster

Leo Fender once said, “I don’t believe that any electric guitar improves with

age. I think that is a myth.” Was he right?

Great collections transcend the objects contained within them: they tell

stories, relay information, create meaning, and convey purpose. The

extraordinary and beautiful industrial designs thoughtfully showcased in this

book range from pristine, virtually untouched examples to those played

passionately night after night.

Years after the golden age of electric guitar manufacturing, Leo couldn’t

comprehend the desirability of the early output of his and his contemporaries’

factories. Throughout his life, he relentlessly pursued perfection through

incremental improvement. This book is a testament to the insatiable drive of

Mr. Fender and his peers.

In the early 1950s, the electrification and mass production of solid-body

guitars and basses sparked a revolution. With amplification, bands became

more efficient and mobile. Louder and smaller, guitars became an attentiongrabbing

lead instrument capable of playing to ever-larger venues. Music

changed forever. The most successful bands of every musical style toured

locally and nationally, building the DNA of modern music. From honkytonks

to hayrides, ballrooms to basements, garages to stadiums, high schools, and

clubs, these stringed instruments evoked joy, passion, hysteria, angst, discord,

and rebellion. The intimate relationship musicians forged with these tools

helped write the soundtrack of the twentieth century.

Mr. Fender was wrong: electric guitars do get better with age. The

presence of those who played them before us forever exists within these

instruments. They are an extension of our collective musical identity and

echoes of the past. Vintage guitar collections of this importance and

magnitude rarely rest in the hands of a musician as accomplished as Geddy

Lee. Geddy’s collection represents every important popular musical genre,

every tone in the bass palette, and is, quite simply, one of the finest of its kind

in the world.

Co-author of Fender: The Golden Age 1946–1970

Alex Lifeson

Geddy Lee is still my best friend. That says a lot about a relationship that has

lasted more than half a century. We’ve shared many remarkable experiences

in that time, both as bandmates and as buddies, but the thickest glue that

bonds us has been our common love of music and musicianship . . . that, and

all his great wine I helped him drink.

For forty-six years we wrote, recorded, and performed some of the most

challenging music we could think of, and I’d often shake my head and smile

at the crazy-cool bass parts Geddy would come up with. They were even

better than the bass parts I thought I could write—mostly! They always

seemed to be just the right combination of smarts and feel that allowed both

Neil and me to explore our own arrangements more freely, especially the

amazing drum parts that I also wrote but, of course, never got used.

Now he’s presented his collection of basses in such a thoughtful and

elegant manner that, I must say, looking at the photographs makes me want to

become a bass player. Whew, shake it off, Al, shake it off!

I’ve been on the other side of the stage while Geddy’s played many of

these bass guitars, and his passion and love for them were evident to me

whenever I saw his huge grin. I know how hard he worked on this gorgeous

book—I’ve hardly seen the guy for the past year, and I’m getting rather

thirsty, but I know what it means to him to be the custodian of all those

incredible instruments with their colorful histories. He didn’t do this for the

big bucks and chicks like I did; he did it because he loves those four-stringed

wonders that have given him so much joy throughout his life . . . and mine.

FALLING DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE

I suppose it was during the spring of 2012 that the notion of acquiring a

vintage bass guitar first lodged in my mind. We had just started gearing up

rehearsals for the Clockwork Angels Tour when I was approached by a music

store with an offer of an instrument swap. They were looking for one of my

stage-used basses to beef up their own “hall of fame” and tried to tempt me

with a mid-1950s Fender Precision in return. At first blush, I wasn’t

interested. I wasn’t a collector (of instruments, at least) and would certainly

never, ever part with any of my main instruments—certainly not the 1973

Rickenbacker 4001 or my current Number One, the 1972 Fender Jazz.

Still, it sparked a series of discussions about vintage instruments with my

trusted bass technician, John “Skully” McIntosh, during which I not only

discovered how passionate and knowledgeable he was on the subject, but also

how little I actually knew about the history of the instrument I’d been

associated with for more than forty years.

So I started reading up on Leo Fender and the early years of the Fender

electric bass. What a leap those instruments represented for the musical

technology of the day, and what it must have meant to players back then to

go from playing a stand-up all their lives to suddenly having a fretted

instrument in their hands. Then I investigated the history behind

Rickenbacker, Gibson, Höfner, and on and on, getting deeper and deeper into

the story of my main monkey business. The genealogy of these various

brands had become, quite suddenly, fascinating to me. And as anyone with

the collector’s gene will tell you, “fascinating” can be a dangerous word. . . .

Allow me to take a moment here to explain something key to my

personality. Once I turn my gaze to a thing with any degree of interest, I

become curious, and feel compelled to research it. Curiosity turns into

“fascination,” which begets even deeper “engagement,” and then, uh-oh, it’s

a full-blown obsession. And I’m, like, Really? Again?

This trait of mine started at an early age with a typically nerdy pursuit . . .

wait for it . . . stamp collecting! (Glad I got that off my chest.) But then, and

not a moment too soon, I discovered music and began to amass a mountain of

vinyl. I started with the West Coast sounds of the Beach Boys and Jefferson

Airplane, then turned to Brit rockers like the Yardbirds and the Who, and

then the more obscure prog bands from the 1970s. (Van der Graaf Generator,

anyone?) Lucky for me, I suppose, all that listening got me obsessed with

figuring out songs—first on guitar and then the bass, spending countless

hours in my room, jamming along with all those fabulous records until I

could mimic my fave bass players.

The “collector’s gene” didn’t surface again until much later in life, when I

was a touring musician with lots of idle time on my hands in the many

different cities of the world I was lucky enough to see. I first became a

devoted student of the game of baseball, watching the Cubs on WGN-TV

every afternoon, as I groggily awoke around midday, after driving all night

from the last gig. Then, having access to so many local museums and

galleries in those cities, I got into photography, which led me to modern art

and architecture, and eventually fine wine and food. I found myself spending

my free afternoons (a working musician should never get up before noon) in

each town’s art institutions, and my evenings in the coolest local restaurants

with the most interesting wine lists I could find. And if I had more than a few

days off, I would scurry off to the nearest wine region—soaking it all up, so

to speak. It was education by complete and total immersion in whatever had

caught my “curiosity.” As the great and wise pianist and raconteur Oscar

Levant once said, “So little time . . . so little to do.” Or something like that.

In the 1980s, my love of watching baseball turned into collecting baseball

ephemera. For me, that was a way of learning about not just the history of the

game but also the history of the US itself from a variety of social

perspectives. Similarly, by the 1990s, my love of wine was taking my family

and me all over Europe on our holidays, building a collection of juice while

learning about the histories and cultures of the places it came from. And so, if

these obsessions had become doorways for me to living histories and glorious

pasts, I suppose it’s not surprising that sooner or later I’d dive down the

proverbial rabbit hole into the world of vintage bass guitars.

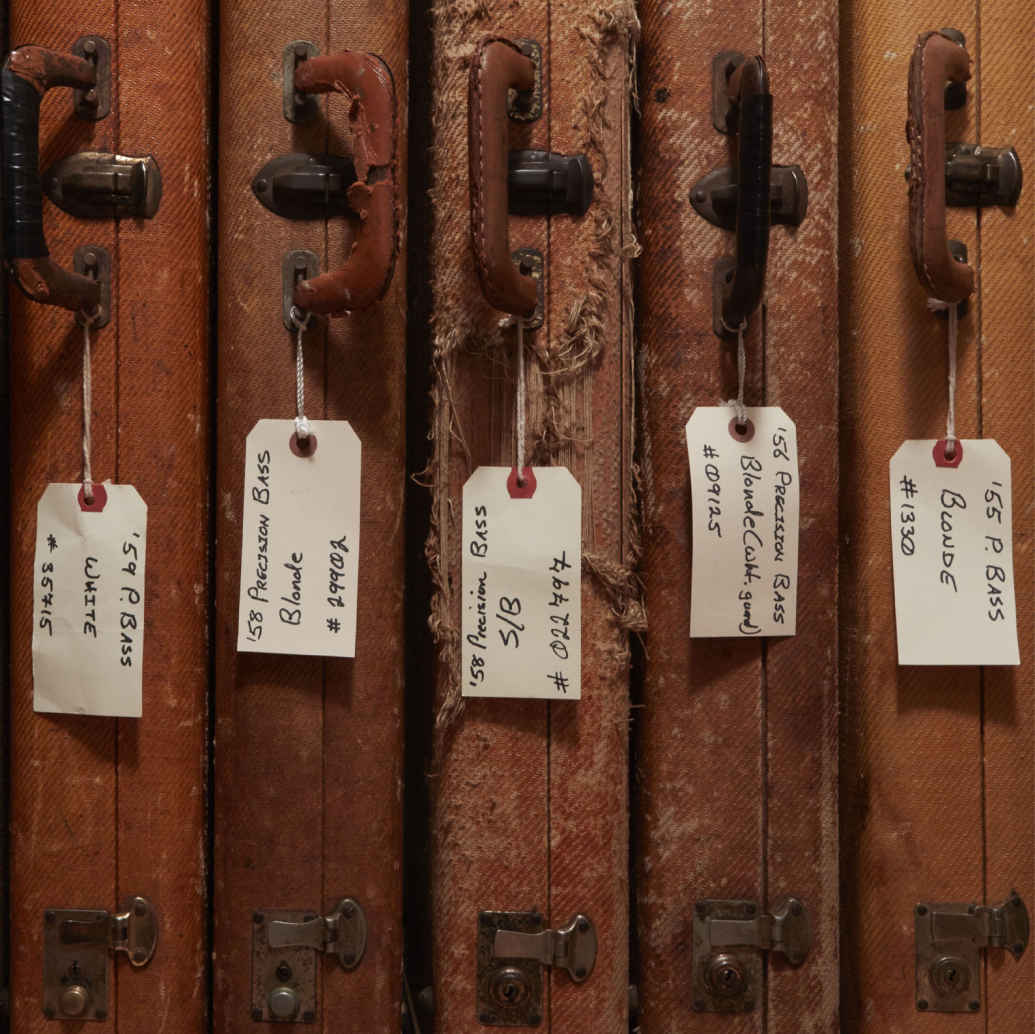

Skully and I first decided we would research a few of the classic basses

played by those musicians I’d admired most as a teen; we’d put together a

“modest” collection that represented my rumbly beginnings. But the more we

looked, the more I learned, and the more I learned, the more I acquired. I

started with Fenders, and in particular Jazz Basses, but eventually got hooked

on instruments I had never played before. They were to me irresistibly

intriguing.

I’d always been very focused on crafting a sound of my own, and I shied

away from instruments I feared might lead me in the wrong direction. That

single-minded approach certainly helped me create my own bass identity, but

looking back now, I realize it may have also closed my ears and eyes a bit.

Forty-plus years later, I’m beginning to understand the craft and the people

behind the various sounds and tones of basses that were always out there and

available to me as both a player and now a collector, particularly those

instruments manufactured in the years between 1950 and 1975. I feel like I

owe it to my bass to do right by it. Silly, maybe, but collectors need all sorts

of reasons to permit themselves the indulgence of collecting.

Anyway, as I was saying, Skully and I began to scour the globe.

Gathering all the basses in one place has allowed me to examine the subtlest

changes in their evolution—aesthetic, electronic, and ergonomic—and I’ve

also been able to check out their fundamental sound. I’ve had a boatload of

fun plugging them in and playing them all (and even road-testing more than

two dozen of them), and doing so over and over, back to back, and side by

side, has allowed me a rare opportunity to get a grip on the very essence of

the bass guitar.

I began to ponder the origins of the thing. My generation’s experience of

the bass is as an instrument that enjoys equal rights. It could sit up-front,

moving the song along melodically, like James Jamerson’s part in “My Girl,”

or mesh with the drums to help create a rhythmic counterpoint, as Chris

Squire does so emphatically in “Roundabout.” But this is a somewhat

contemporary point of view. What about the role of the bass back in the day?

Well, historically, while there certainly have been concertos for the double

bass, and the instrument did enjoy a period of popularity as a solo instrument

in the 1700s (and the basses introduce the final theme in the fourth movement

in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony), it’s fair to say that bass has literally been

second fiddle to the main event.

As music evolved (or devolved, depending on your taste), so did the

shape and the role of the bass, and plucking began to take precedence over

bowing. According to Jim Roberts, the author of How the Fender Bass

Changed the World, the great-granddad of the modern electric bass was the

sixteenth-century bass lute. Big boys like the theorbo and the chitarrone

sometimes had strings five feet long to produce superdeep notes. Evolving in

parallel was the bass viol, of the violin family, which became the contrabass

—although it was designed to be bowed. Then, in the early twentieth century,

along came the mandolin orchestra boom (yes, that was a thing) and with it

the fretted mandobass, made specifically for pluck-minded players and tuned

to E-A-D-G like a double bass, setting the stage for the modern bass guitar.

The advent of electricity fired up both musicians and inventors. Oh, the

possibilities! Telephone transmitters were being placed inside violins and

banjos, carbon-button microphones were tinkered with, everyone wanted to

get louder. Finally, in 1932, the Ro-Pat-In Corporation in Los Angeles began

commercial production of the Rickenbacher Electro A-22, a.k.a. the Frying

Pan, the first stringed instrument with a pickup. But that was a six-string; if

you were a bass player in a dance band, you must have stood at the back of

the orchestra with your double bass, wondering, “When is it my turn?”

Over the next twenty years, there were stabs at louder bass design: Dobro,

for instance, offered a bass version of its metal resonator; and the Electro-

String Instrument Corporation (as Rickenbacker was then known) created the

metal-body Electro Bass-Viol, which required its endpin to be plugged

directly into the top of an amp. The earliest bona-fide solid-body electric bass

—as we’d recognize one today, played horizontally and reliant on a pickup—

was the Audiovox Model 736, designed by Seattle’s Paul Tutmarc in 1936.

He really should be popularly credited with conceiving the very first, but with

World War II and other events getting in the way, it didn’t happen for him.

So it was, in 1951, that Clarence Leonidas Fender—better known to us

guitar nerds as Leo—introduced the Precision Bass, “freeing the bass from

the doghouse,” to use his own words. And that is sort of where I come in; or

more precisely, where my collection does.

In the course of my various other pursuits, I’ve learned that the true

collector’s mind-set—and for the most part, one I share—is about condition,

condition, and, oh yes, condition, but with guitarchaeology, the condition of

an instrument tells me only half the story. Most collectors want only pristine,

untouched, and unplayed instruments that have been under beds and in

closets in suspended animation for decades; the cleaner they are, the more

valuable they are to them. I get that, but what about the instruments that have

lived a life?

What about the well-worn, smoky, sweat-soaked instruments that have

played the bars, played the high schools, paid their dues at the weddings and

the blues festivals, truly earning and showing their age spots, having not only

made a living for their owners but also given their audiences pleasure? Those

instruments have real effin’ mojo to me. They don’t necessarily have to have

been owned by the famous, just by everyday working musicians—whether

professionally or as weekend warriors, it doesn’t matter; whoever it was who

played because he or she loved to play, who wore the frets down to the

fretboard and the paint down to the undercoat while doing so. Those are the

instruments with stories to tell, not in so many words but in the way they look

and the way they feel when I pick them up to play them myself. In this era of

“relic’d” instruments—new but made to look artificially road worn—I feel

it’s important to find the real deal to give context to what that idea of playing

music really means. You can reproduce a look but not the life lived.

That being said, as usual I wanted it all: both the wall-hangers and the

players, and a bunch that fall in between—but you can’t play 250 all at once

—at least, I can’t—so why not share them with other bass geeks and

collectors with the same affliction? To quote Steven Wright, “You can’t have

everything. . . . Where would you put it?” The answer is, in this book.

The title notwithstanding, I haven’t done it all alone. From the outset, I

knew I’d need a damn fine photographer with enough experience and

creativity to snap hundreds of basses and keep them interesting, a far more

difficult task than you might imagine. Instruments often have contours,

angles, and features that defy easy translation to the page; their beauty lies in

both the macro and the micro, and above all their colors are hellishly difficult

to capture accurately—especially when you have a world of guitar geeks

(starting with myself) to please, who are extremely particular about such

details. I’m sure you will agree that Richard Sibbald has made these bass

guitars look as lush and varied as the tones that they produce.

Along this journey of discovery, I also realized there were instances in

which my or Skully’s knowledge was wanting, so I also leaned on several

discerning and experienced collectors, players, and guitar builders to make

sure we didn’t miss the key historical facts, the juiciest details, and the most

esoteric minutiae. For the generous contributions of their time, scholarship,

and good humor, I will be forever grateful.

Thirdly, wrangling words is not quite as easy for me as wrestling with

notes. Fortunately, I just happen to be good friends with a guy who not only

plays guitar and knows a hell of a lot about music, but who also encouraged

me from the beginning to dive into the project. That person is my longtime

pal, the author and journalist Daniel Richler, who’s dedicated himself

throughout this project to keeping me clear and focused and very me on the

page (without using too many f-bombs).

I know that when one gets truly engaged in a subject, it’s hard to resist

the tendency to go on a bit. So I’ve tried as best as I can not to be obnoxious

with obscure bits of information. (Fail!) Reference books and the internet

abound with that kind of detail, both right and wrong, and I’ve tried to keep it

to a minimum—but sometimes it’s irresistible. Out of consideration for the

rest of the population, we’ve created sidebars and various notes (or, as I like

to call them, “nerd bubbles”) that contain all manner of technical and

historical data, so that those of you who somehow feel content to live your

lives without such extra information may feel free to ignore any or all of them

and get down to looking at the basses.

Finally, you’ll see that there are interviews, comments, and quotes from

my fellow bassfolk spread throughout this book. I have to say, I had such a

blast visiting, grooving, and corresponding with them; I truly did not

anticipate how rich and revealing their stories would be. Some share the same

madness for collecting, some have collections that contain one-of-a-kind

historic instruments, but all of them share the same love of playing the bass

that I possess. But more contextually, these conversations shed light on the

world of rock I’ve been fortunate enough to play a part in. Apologies if your

fave bassist is not featured here as I would have loved to talk to even more,

but I simply ran out of time and pages.

I hope you enjoy the trip.

FENDER

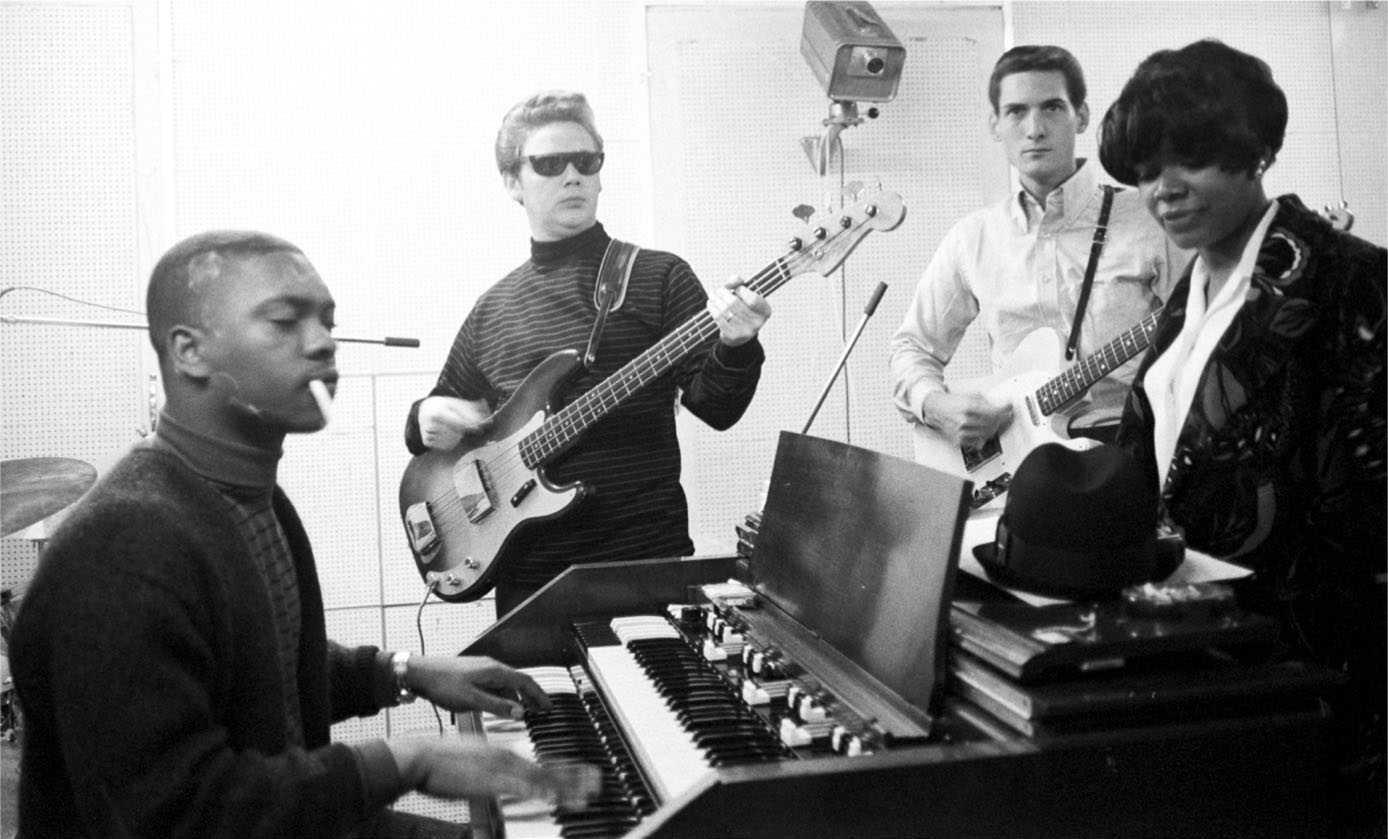

When I was boy, the radio was always on in my mother’s variety store. In

those days, it was pure top forty: all the hits, all the time! It’s there I had my

first exposure to the Beach Boys, Booker T. & the MGs, Stevie Wonder, the

Supremes, and Aretha Franklin, to name a few. I didn’t know it at the time,

but I was subconsciously absorbing the glories of Fender, in particular the

Precision Bass in the hands of Brian Wilson, Duck Dunn, and James

Jamerson. My interest in music was sparking, and soon enough I’d be poring

over album covers and rock magazines, identifying the guitars in the hands of

those stars.

Fast-forward a couple of years: now a bassist with ambitions, ready to

ditch my cheapie bass and standing in a shop, about to buy a 1968 Fender

Precision. The salesman assured me it was a real “workhorse”—and I knew

straightaway that was something I planned to exploit. I surely did play that

thing, day and night. It was never far from my sight. I even loved the smell of

it! And so began my long, if interrupted, history with the brand.

Fast-forward a couple of years: now a bassist with ambitions, ready to

ditch my cheapie bass and standing in a shop, about to buy a 1968 Fender

Precision. The salesman assured me it was a real “workhorse”—and I knew

straightaway that was something I planned to exploit. I surely did play that

thing, day and night. It was never far from my sight. I even loved the smell of

it! And so began my long, if interrupted, history with the brand.

Fender has always been there in my life, not always up-front but as a kind

of benchmark by which all other basses are judged. I had some steamy affairs

with other brands such as Rickenbacker, Steinberger, and Wal, but something

about Fender would eventually draw me back. I learned so many

fundamentals with that ’68 Precision, and while there’s no denying

Rickenbacker’s influence along the way, since the mid-1990s my more

modern sound has been based on my Fender Jazz of 1972.

Of course, playing an instrument is one thing; knowing its genealogy is

quite another. If ever I had a question that even Skully couldn’t answer, we

sought out Terry Foster, the co-author of Fender: The Golden Age 1946–

1970, who probably knows more about Fender than anyone else on the

planet, and whose collection of Fender memorabilia squirreled away in his

Toronto home is mind-blowing. His insights (as with those of other

specialists in other chapters) have been a great help to me in my mad quest

and are sprinkled throughout the upcoming pages.

PRECISION BASS

I can still remember the feel of the wide neck and the rumble of the furniture

(and everything else, for that matter) in my teenage bedroom. When I first

plugged in that brand-new ’68 P-Bass and turned it up loud, it was such an

awesome, visceral moment that I didn’t stop to think about its origins. I

didn’t care then, but I certainly do now.

Leo Fender’s concept for the instrument was that anyone who could play

a guitar could now play the bass. He and his partner Don Randall named it

the “Precision” because with frets you got the notes you wanted, and in tune.

Everything that Leo did, in fact, was geared for utility, because first and

foremost the man was an inventor and a gadgeteer. Rather than hire luthiers

and seasoned craftsmen, such as those who worked over at Gibson, he mostly

employed factory workers. Fender in the early 1960s was a classic example

of the all-American assembly line.

After the Precision’s introduction in 1951, Leo kept tinkering with his

invention and making a ton of improvements over a ten-year period. I’ve

been fascinated to learn how that flat, stretched-out slab of wood morphed

into a more streamlined, curvaceous, and utterly reliable, not to mention

terrific-sounding, bass guitar that became the standard for so many musicians

of all stripes. Assembling this collection has reignited my love of the

instrument—playing them live on the R40 Tour, even more so. But enough

talk. Let’s take a look!

1952

Fender Precision Bass

BLONDE

Bassmen! The electric bass arrives! It may not have been the very first, but it certainly was the first mass-production model. The Fender Precision was born in late 1951; this particular, pristine example dates to July 1952. One look, and you can see why it’s called a “slab”: a noncontoured ash body with a Blonde nitro finish and a one-piece maple neck. The truss rod is loaded from the back, and the slot is filled with a walnut strip commonly referred to as the “skunk stripe.”

Mon dieu! Shock, horror! We dared to turn the screws on this all-original sixty-plus-year-old beauty, so you could see the details of the neck assembly. Here’s a good look at the black fiber pickguard with its finish of lacquer that adds depth and shine, as well as the neck and body dates written in pencil by “TG”—Tadeo Gomez, one of Leo Fender’s workers.

1953

Fender Precision Bass

BLONDE

This 1953 Fender Precision Bass Blonde marks the beginning of my madness: it was my first 1950s acquisition. Wine geeks like me look for vintages from their birth year, so naturally I wanted the same in a bass. Now you know how effin’ old I am.

Originally designed for the Broadcaster and made in small batches, the early profile of the tone and volume knobs subtly changed over the years: the ’52 and ’53 both had slightly rounder domes, were flatter on top by 1955, and continued morphing until 1957, when they achieved the flattop shape they still have today. Regardless, they’ve proved indestructible.

NO BASS!

In late 1949, Leo Fender’s partner Don Randall returned from the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM) trade show, where he’d exhibited Fender’s new Broadcaster (later called the Telecaster, due to copyright issues) guitar. Everyone had laughed at the “plank and canoe paddle,” but Don’s most urgent concern was getting a truss rod in the thing. Leo was famously frugal and didn’t think it was needed. He thought of his instruments as modular consumables: when your frets wear out, just bolt on a new neck. A truss rod would take time and finesse to install. But in the end, Leo found a clever way to do it without having to create a more expensive two-piece neck. The important point, Terry Foster argues, is that without that truss rod, Leo would never have been able to make a bass—not with that scale of neck, a neck that could withstand the tension of its strings. The next most urgent issue was, where do you even get strings for an electric bass? Leo’s solution? Use piano strings.

1955

From 1951 to 1960, the Precision Bass was in a state of almost continuous transition, as Leo sought to perfect his bass. The first significant change came in 1954, when the shape of the instrument began to move away from the slab to the more comfortable Strat-like contoured body, as the P-Bass began to resemble that of the bass we know today.

Left to right: The Precision Bass’s first transition period: early ’55 Blonde, ’55 Sunburst, later ’55 Blonde

1955

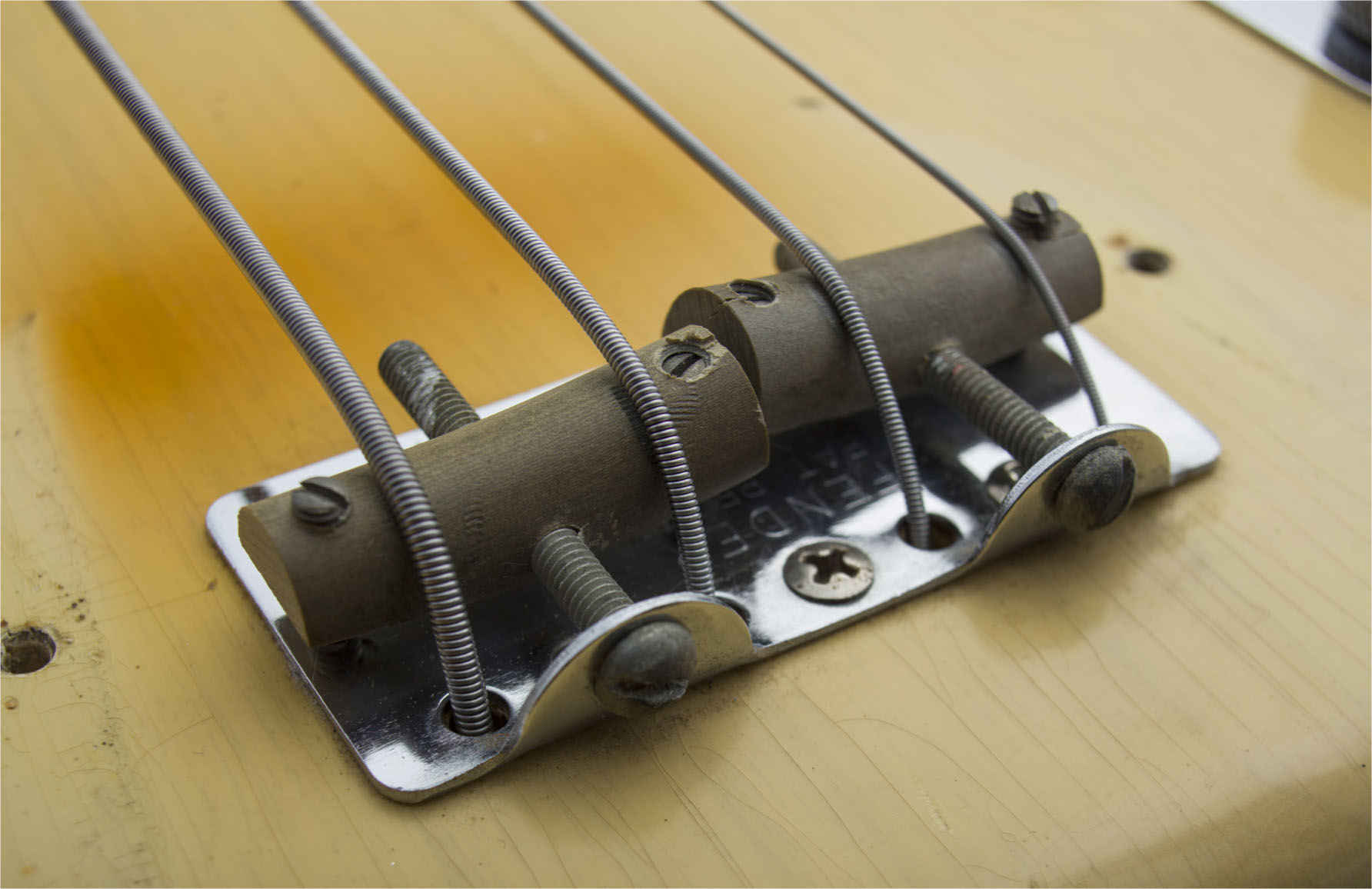

Fender Precision Basses

BLONDE

Changes afoot. As of 1954, steel saddles were replacing phenolic. The serial number is still visible on this bridge plate, yet that same year the placement of the serial number was transitioning to the neck plate. Some basses exist with the serial number in both locations.

An example of a later bass with the earlier phenolic saddles. Nothing goes to waste in a guitar factory.

Fender typically used “swamp ash” for these see-through Blondes, as opposed to alder for the Sunbursts. It took much more work to prep ash because of its porous nature—it had to be filled in with a shellac sanding sealer—but the beauty of the result is self-evident.

Out of curiosity, I played both of these Blonde ’55s back to back for quite a while to see if I could discern a noticeable difference attributable to the phenolic saddles as opposed to the steel. It must be said, the results are inconclusive, as no two pickups are identical. However, the bass with steel saddles was a little brighter and had more sustain.

1955

Fender Precision Bass

SUNBURST

In 1955, the transition continued with the introduction of the new two-tone Sunburst finish. This one is made of alder, and has a gleaming white plastic pickguard.

The serial number, no longer visible on the bridge, fully transitioned to the neck plate in 1955.

These black staggered pickup poles were introduced in 1954, in an attempt to balance the output of each string.

1956

Fender Precision Bass

BLONDE

From a year that mostly saw Sunbursts being produced came this well-loved bass with the rare combination of Blonde finish and an original white guard.

GEDDY LEE’S BIG BEAUTIFUL BOOK OF BASS. Copyright © 2018 by Dirk Music Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverseengineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Published in 2018 by

Harper Design

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

Tel: (212) 207-7000

Fax: (855) 746-6023

[email protected]

www.hc.com

Distributed throughout the world by HarperCollinsPublishers

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

Fender, Fender in script, Bassman, Jazz Bass, Precision Bass, and the distinctive headstock commonly found on Fender guitars and basses are registered trademarks of Fender Musical Instruments Corporation and used herein with express written permission. All rights reserved.

All photographs by Richard Sibbald unless otherwise noted. www.richardsibbald.com

Chapter title spread photo concepts: Daniel Richler

Every effort has been made to provide credit information for third-party images. Any error will be corrected in subsequent reprints.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

Digital Edition DECEMBER 2018 ISBN: 978-0-06-274784-6

Version 11272018

Print ISBN: 978-0-06-274783-9

Geddy Lee's Big Beautiful Book of Bass