|

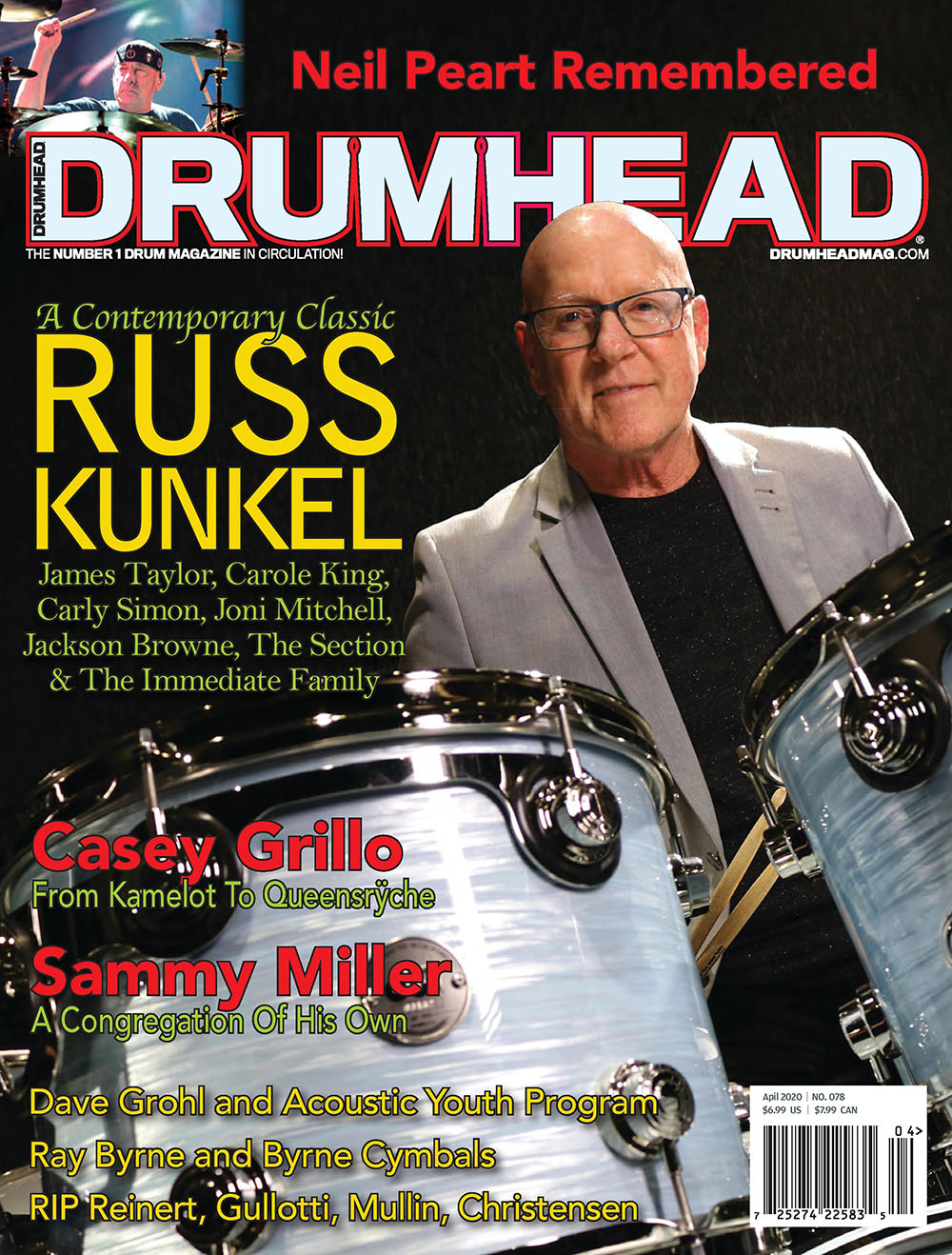

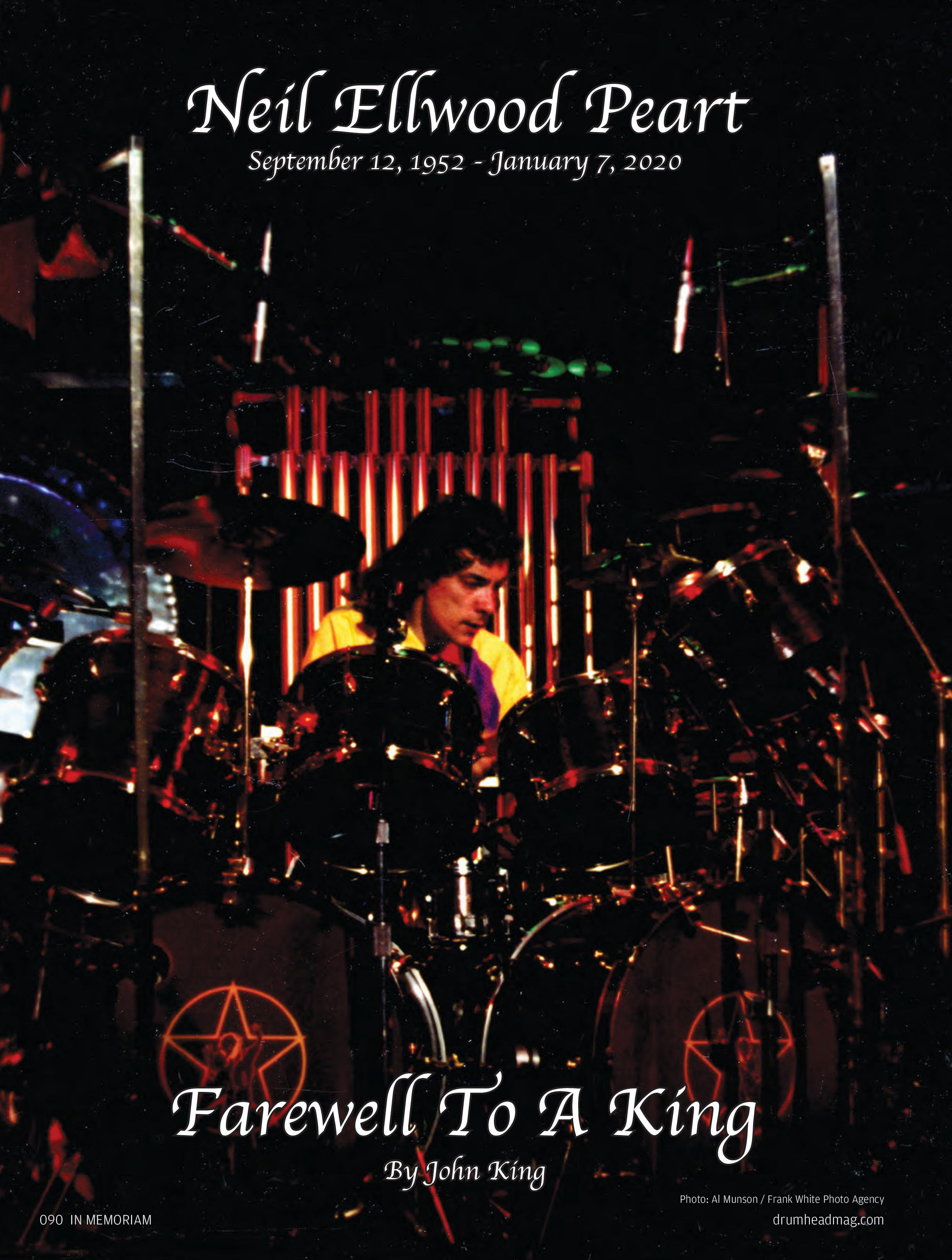

Drumhead Magazine April 2020 by John King |

There is an entire generation of people who know

exactly where they were when they learned John F.

Kennedy died on November 22, 1963. And now there

is an entire generation of drummers who know exactly

where they were when they learned that Neil Peart

passed away on January 7, 2020.

Headlines everywhere referred to him as Rush’s

“drummer and lyricist.” But describing Neil Peart as

simply a “drummer and lyricist” is like saying Joe Di

Maggio was merely a “ballplayer and coffee machine

salesman.” There was much more to the man, and the

story. Neil may have left us at only 67, but he epitomized

the maxim, “It’s not the amount of years in your life, it’s

the amount of life in your years.”

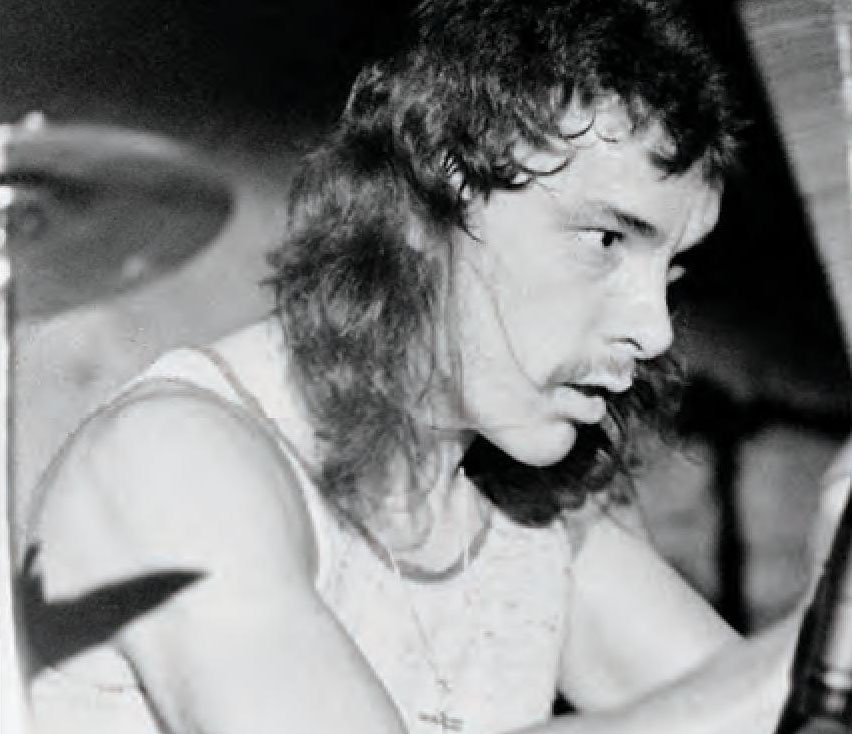

Neil Peart was the most influential drummer of his

generation, and arguably one of the greatest of all time.

Debates about technical minutiae will always persist, but

quite simply, no other drummer had as much influence,

and for as long. Neil was an integral part of the band

Rush from his debut with them in 1974, until his passing

in 2020. They sold over 40 million albums, packed arenas

for decades, released numerous music videos, earned

prestigious awards, and enabled Neil to create his own

infotainment documentaries about the art of drumming.

On top of all that, Neil was also an author, birdwatcher,

bicyclist and motorcyclist, an eternal student, a true

individual, and a husband and father.

The talented, adventurous, driven autodidact who is

probably the most “air-drummed-to-drummer” of all

time ignited a spark in countless kids to play real drums,

and defined what a progressive rock drummer could be.

The high personal standards he set for himself raised the

bar for everyone else. His playing became the proving

grounds for rhythm seekers. If you could play his parts

correctly, you were deemed serious.

The talented, adventurous, driven autodidact who is

probably the most “air-drummed-to-drummer” of all

time ignited a spark in countless kids to play real drums,

and defined what a progressive rock drummer could be.

The high personal standards he set for himself raised the

bar for everyone else. His playing became the proving

grounds for rhythm seekers. If you could play his parts

correctly, you were deemed serious.

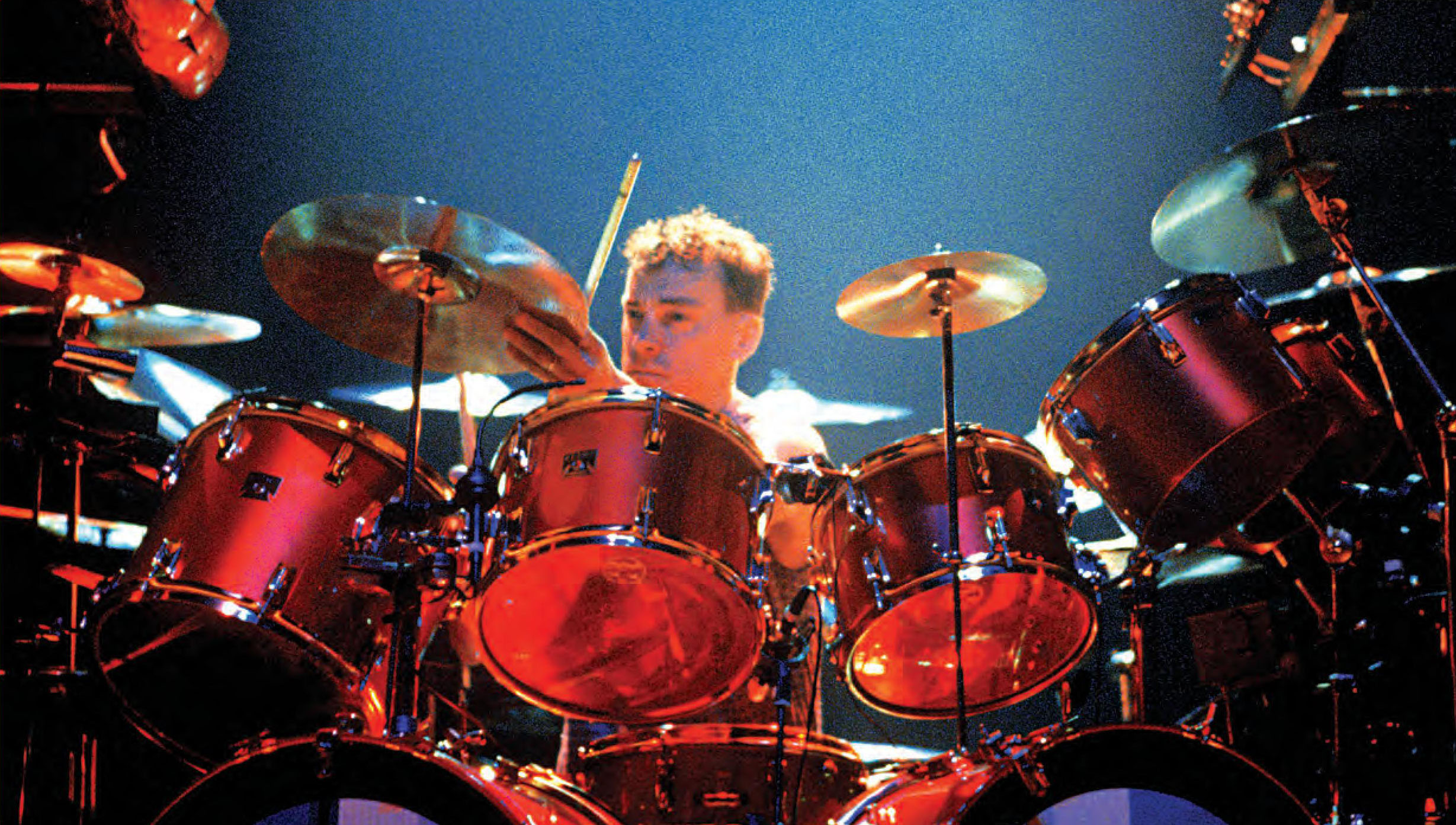

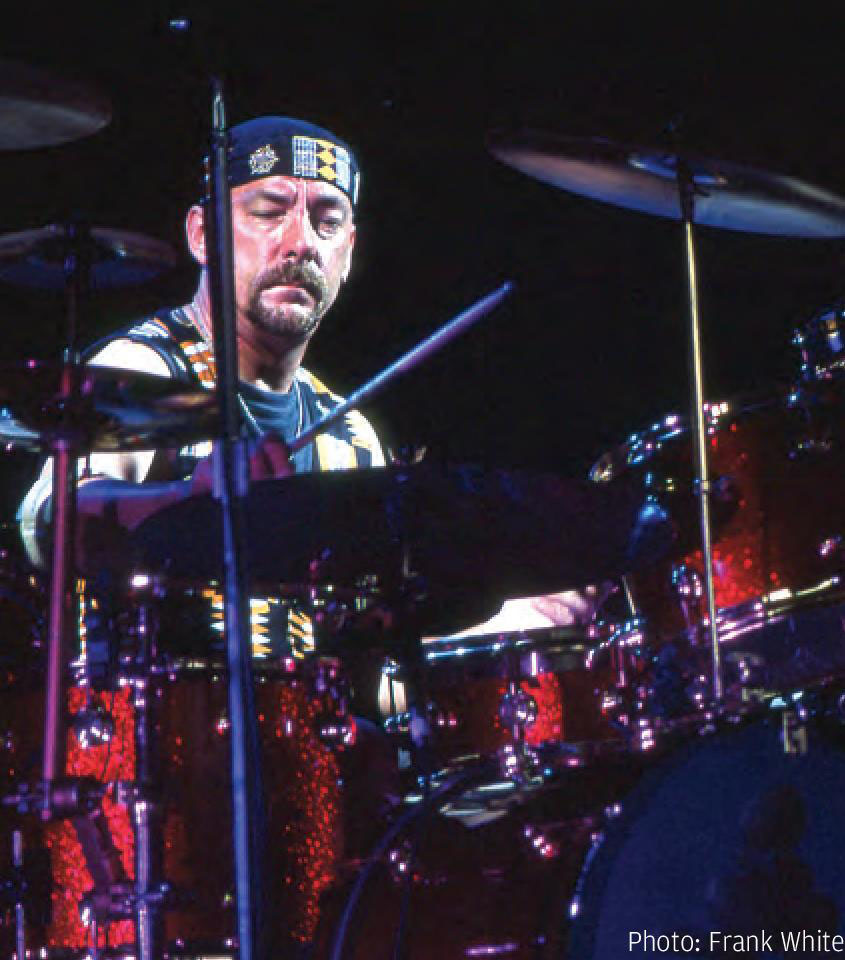

Neil Peart played with power, passion and precision.

He flowed seamlessly in and out of odd time signatures.

He understood composition, and enhanced Rush’s music

with his creativity and execution. He utilized the snare

drum for more than just two and four; he played lengthy

phrases on it that harkened back to the big band era

that he loved so much. His snare drum forays typically

led to tom toms, and Neil was a master of shifting gears

during fills. He created a rush of excitement like no other

drummer with his exhilarating rolls around the kit, which

always had an incendiary drum sound.

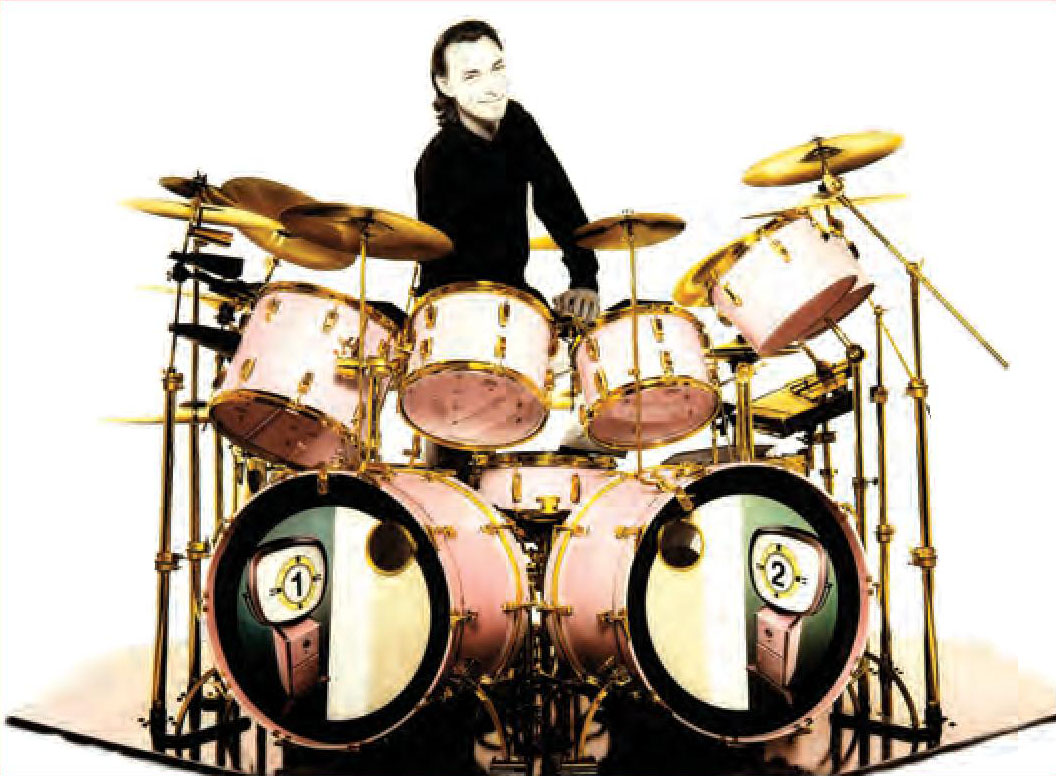

Some drummers think “less is more.” Neil believed

“more is more.” He expanded the boundaries of the drum

set. His large double bass configurations caused drum

fever among novices and professionals. But refreshingly,

his immense instrument was not for show; he used every

item on his drum riser, from the tiniest splash to the gong

bass drum. He also incorporated discoveries from his

far-ranging travels: exotic instruments, world rhythms,

the spirit of adventure, and the warmth of humanity he

encountered all over the world.

His “more is more” ethos also permeated his

drumming. Neil often played more notes in one song

than some drummers played on an entire album. And he

played more notes on an album than some drummers

played during their entire recorded careers. That does

not mean the man played recklessly though, like his first

drum idol, Keith Moon. Neil developed his own style,

and pulled off a magic trick in the process. No matter

how complex his playing became, it hit you right in the

chest, and it felt great.

Neil had a strong work ethic and gave his all onstage,

and in the studio. Lest anyone think those signature

parts simply flowed from him on “take one,” here are

his own words about the process. “My method is to try

everything I can think of, everything that might possibly

work, then gradually eliminate the ideas that are less

satisfying: wrong, bad or just plain dumb. Over a period

of several months, I work(ed) through each song, playing

them again and again, refining the structure, the rhythmic

and the textural elements, and smoothing the transitions

between them.”

That kind of dedication led to his studying with Freddie

Gruber nearly thirty years into his drumming journey,

when Neil was widely considered among the best of the

best. Many did not understand this move, but Neil was

basically self-taught, and had reached a point where he

felt stiff, and restless. He wanted to push himself, open

up a new frontier, and challenge his limitations and self-expectations.

He did all of that, and more.

Unlike other pros who revamped their styles privately

in mid-career, Neil documented his progress and created

instructional media so other drummers could learn from

his endeavors with Freddie. He took notes during his

epic bicycle journeys and turned them into “The Masked

Rider,” an enjoyable travelogue. Amazingly, his openness

flourished even after he experienced the incredible dual

tragedies of his daughter Selena passing away in 1997,

and his wife Jackie following shortly after, in 1998.

Neil needed to retire from Rush for a while after those

two life-changing events. Fortunately, his bandmates,

best friends, and soul brothers Alex Lifeson and Geddy

Lee, understood. They stepped back as Neil swung a

leg over his BMW motorcycle, and then rode across vast

parts of planet earth. Neil’s extensive note taking and

reflections on life led to another successful book, “Ghost

Rider.”

But he was still a drummer at heart. And when he

was ready, he came roaring back. Sonically, his return

was recorded via the Vapor Trails album. Visually, it

was documented via “Rhythm & Light,” a collection

of beautiful black and white photography that was a

collaboration between Neil, and his wife Carrie, who

he married in 2000. The images and words revealed a

side of Neil never seen before, and launched him into a

second chance at life with his new wife, and eventually,

their daughter Olivia.

The once aloof and ultra-reclusive drum star who

still believed wholeheartedly in the lyrics he wrote

for “Limelight” revealed even more of himself to the

world through his playing, writing, interviews and more

instructional videos. He was self-aware, yet self-effacing

and extremely intelligent. When facing a challenging

situation, he’d ask himself, “What would a smart person

do?”

As a teen, Neil was a fan of Ayn Rand’s objectivist

ideology. It was his raison d’etre, and inspired him to

become his own (super)hero, riding the public buses of

Toronto wearing a purple outfit, complete with a cape

and permed hair. This deep level of conviction also

fueled his early sci-fi based lyric writing. However, with

maturity came wisdom, and empathy. He eventually

disavowed Rand, identifying himself as a “bleeding heart

libertarian” who practiced enlightened self-interest. This

evolution was also reflected in his lyrics.

Neil once commented that he wished Rush’s career

had begun with the Moving Pictures album, because all

of their previous musical and lyrical output was a matter

of experimentation, fantasy and fun. However, everything

came together on Moving Pictures. The band wrote

concise, catchy songs that retained their complexity,

and said more in five minutes than they previously did in

twenty-five.

Neil once commented that he wished Rush’s career

had begun with the Moving Pictures album, because all

of their previous musical and lyrical output was a matter

of experimentation, fantasy and fun. However, everything

came together on Moving Pictures. The band wrote

concise, catchy songs that retained their complexity,

and said more in five minutes than they previously did in

twenty-five.

That winning combination continued into the Signals

album, and produced the song “Subdivisions,” which

perfectly described growing up as an outcast in suburbia,

and resonated on a deep level with massive amounts of

listeners. Every legendary band has a career defining

moment, and for Rush, this was it.

According to Neil, “‘Subdivisions’ happened to be an

anthem for a lot of people who grew up under those

circumstances, and from then on, I realized what I most

wanted to put in a song was human experience.” He did

just that, and never looked back as he continued onward

and upward until he retired while still at the top of his

game in 2015, in order to spend more time with his family.

Now, it is our turn to look back on the life and times

of an individual who showed us what is possible on the

drum riser, and in life. He left a vast legacy of words and

music that will be cherished for generations. After he

passed away, following a valiant three-year battle with

glioblastoma, many “lost” interviews have surfaced,

providing new insight into his mastery.

Neil truly believed that the absolute highest goal of an

artist was to inspire others, and that the highest possible

compliment was if someone that you admire respects your

work. Based on the outpouring of affection, reverence

and tributes to him in the Drumhead community and

beyond, he certainly attained those lofty heights.

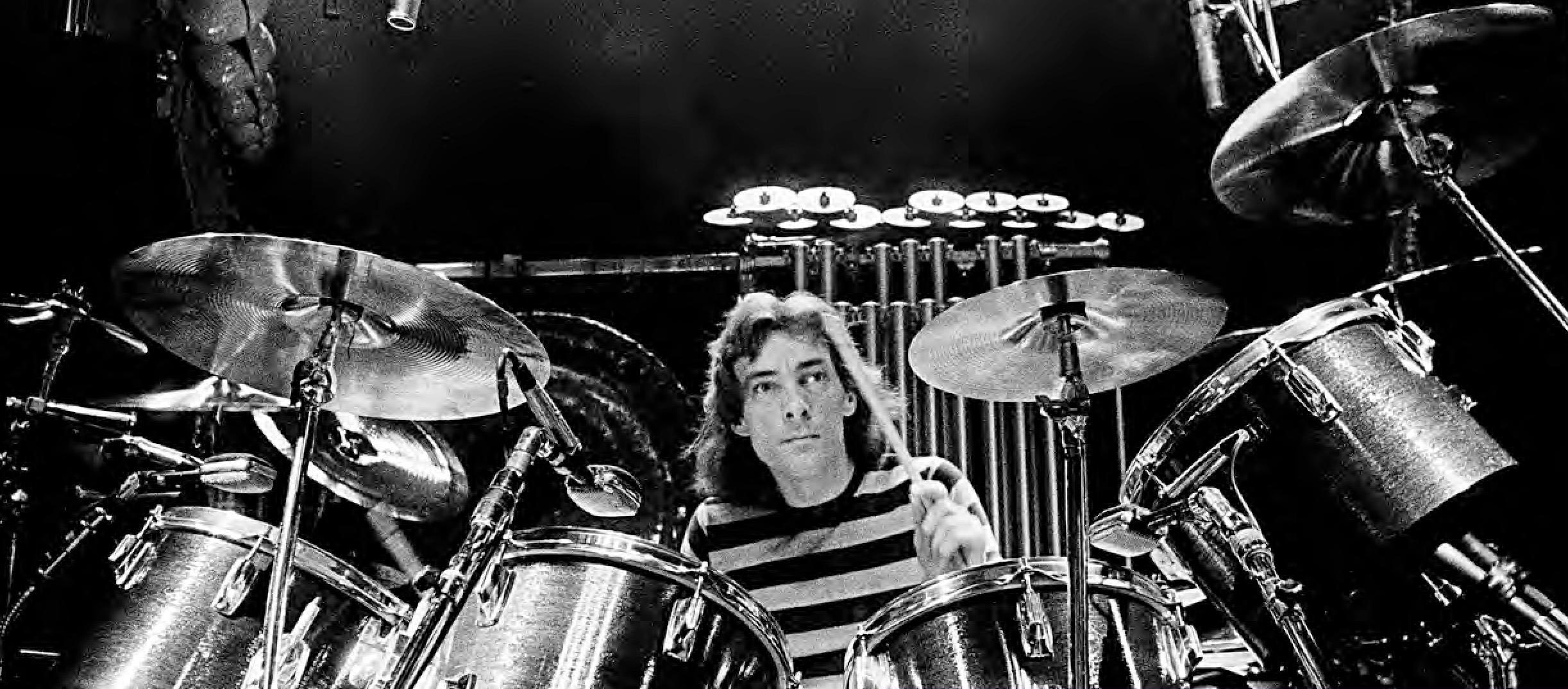

MARTIN DELLER

A Man with Many Voices

“Beautiful, shiny, circles and lines - magical!”

I’d only known Neil a couple of hours when he asked

to borrow my hi-hat pedal. It was 1979. My band, FM, was

opening for Rush at Varsity Stadium in Toronto. We were

new kids on the block Rush had taken a shine to. Neil’s

hi-hat collapsed during sound check. You always needed

- ‘two for the show’. Could they borrow my backup? A

Slingerland, as it happened.

“Yeah. Sure.”

I got it back three months later. Bronzed. He laughed

when I told him. And was, of course, in my debt forever.

The gold plate era came later. Beautiful kits. And then

drum and cymbal design with DW and Sabian. You could

recognize Neil in all those little details, he was always

looking for something – always moving…

It was the Moving Pictures tour that really cemented

our friendship. They were a great band to tour with. Rush

treated you like equals on the road at a time when most

didn’t. They wanted the whole show to be great. One

night, in the middle of our set, during a hard stop in one

of our tunes, we heard this clatter behind us. It took a

moment to realize that Neil was playing along behind us!

He would go under the shroud covering his show kit and

warm up! Too funny. But oh, so practical. Wasn’t long

before he had all the breaks down.

It was the Moving Pictures tour that really cemented

our friendship. They were a great band to tour with. Rush

treated you like equals on the road at a time when most

didn’t. They wanted the whole show to be great. One

night, in the middle of our set, during a hard stop in one

of our tunes, we heard this clatter behind us. It took a

moment to realize that Neil was playing along behind us!

He would go under the shroud covering his show kit and

warm up! Too funny. But oh, so practical. Wasn’t long

before he had all the breaks down.

We had some memorable sound checks on that tour;

the six of us wailing away. A lot of fun. There is a tape. I

bet they have a ton of them. Could make for some very

cool, ‘official’ bootlegs.

Rush toured constantly. Often with a ‘6 in 7’ schedule.

Exhausting after eight to 10 months. Many of the

musicians they hung out with were those on tour with

them. Neil was like a sponge, soaking up ideas from

everyone – forget playing along to records – here’s the

band, live, in front of you! Ha! They grew up in arenas

and concert halls. Imagine how that shapes your playing.

And Neil did play to records - his own! He would

famously rehearse to rehearse. After the Moving Pictures

tour, I visited Neil at his home outside of St. Catherines,

ostensibly to interview him for “Canadian Musician”.

It was an evening of shared enthusiasm for music,

drumming, and automobiles. Some of our wide-ranging

discussion on influences, style and composition did

eventually make into to that article.

Neil had just finished renovating a space above the

garage into a practice studio. He explained that before

a tour he would sit down and play along to his own

records. We laughed. It was how we started – playing

to records! The irony was not lost, but it was smart.

“At least someone knows how the song goes!” Rush

rehearsals often started out sounding like a band trying

to play Rush. It also meant he remembered all the parts

everyone in the audience knew so well.

His was a classical music approach to performance. I

grew up on rock and roll but was schooled in jazz. I took

a more improvisational approach using the song as a

framework to build upon. He said the studio was where

he improvised, the stage was where he tried to get it

right. Every night. And more often than not, he did.

He surprised me by knowing the origin of much of what

he played, where a lot of his shit came from. We shared

influences and insights and learned a great deal from

each other. He would call me up to review transcripts

of his playing that someone had done. “Tell me if this

is what I’m playing!” (I’d had a more formal education)

Then I had the fun of analyzing what he was actually

playing. He was very generous with what he was up to

and interested in what you were doing. Lots of back and

forth - where something came from, how it developed -

playing, composition, lyrics, philosophy, books. He had

this ridiculous memory for things.

Both of us embraced the new tech, drum machines,

electronic drums and samplers. They were just another

voice.

After the Moving Pictures tour, our friendship grew

more personal. We both had young families and Neil’s

daughter, Selena and my son, Shane were the same age.

“Perfect,” said his wife, Jackie, “You must come up to

the Laurentians!” She and my wife, Melanie hit it off and

we spent many a summer and winter vacation up at their

cottage.

His cottage in the Laurentians fronted onto a classic,

northern lake. Deep, clear, and fresh. Neil had fallen in

love with the Laurentians while recording at Le Studio.

It was a magical place. Deep in the Boreal forests north

of Montreal, dotted with beautiful lakes he bought a

modest cottage on one of the small lakes.

Neil was competitive. That first summer there, I decided

to swim across the lake, a bay, to a rock, a piece of the

Canadian Shield, that was not far, eight or nine hundred

yards maybe. As I turned to swim back, I see Neil and

Jackie in their little paddle boat, madly paddling across

the bay towards me. Turns out for Neil, flying wasn’t

the only thing he didn’t like. As a child, he had almost

drowned and was really nervous in water away from

shore. I let myself be rescued amid admonishments to

not be so foolhardy again.

However, Neil was never one to shy away from a

challenge, and with Jackie riding shotgun in the paddle

boat, wasn’t he was swimming the length of the bloody

lake by the next summer! We would swim for about an

hour at a fairly determined pace and then for the last one

hundred yards or so we would sprint! Killer. “Drum solo”

he called it.

Neil was very disciplined, even on holiday up at the

cottage, he would a set routine for the day and follow

through on his plans, not just letting the days flow by. Up

early - for rockers and way ahead of everyone else - he

would prepare a Spartan breakfast of freshly squeezed

orange juice and two boiled eggs with toast for the two

of us. If it was winter, we were off on a 25 km cross-country

ski jaunt packing water with a chocolate bar for lunch.

Neil was very disciplined, even on holiday up at the

cottage, he would a set routine for the day and follow

through on his plans, not just letting the days flow by. Up

early - for rockers and way ahead of everyone else - he

would prepare a Spartan breakfast of freshly squeezed

orange juice and two boiled eggs with toast for the two

of us. If it was winter, we were off on a 25 km cross-country

ski jaunt packing water with a chocolate bar for lunch.

I loved it. I would curse and respect his regimen. We

shared a lot that way, one initiating, the other happy to

engage. We had totally different styles. I was much more

verbal when the going got tough, swearing like a sailor.

He silently simmered at adversity, but one time, the climb

got the better of him and he thrashed an unsuspecting

tree with his ski pole, only to realize too late that he

would need it to ski home! We always laughed at our

misfortunes - later. The crisp air, dry snow, -10 degrees

C – ‘green wax days’, we called them.

When we were able to, we would hang out at each

other’s shows. I met Brutus, in fact, when Neil and Jackie

brought an old school friend of Jackie’s and her husband

to a summer jazz gig I had at the Bellair Café in Yorkville,

a supper club in Toronto. He wasn’t Brutus quite then.

Jackie would often come out to FM shows when Neil was

on the road. She was a very dear friend.

Neil was a big kid. One afternoon, years later, Neil

and Jackie invited us to their new place in Toronto for

a Christmas get together. Behind their house sat the

St. Clair reservoir and with a good snow it created a

wonderful hill to toboggan on. But this was the time

of the GT Snow Racer! Neil, ever the kid, suggested to

Keeley, my daughter, who was about five at the time, that

we should go try the racers out. It was too funny to see

him, all 6’4” of him, hunched over the little GT Racer.

Off the two of them went, down the hill, fast. Neil was

ahead and knew about a turn at the bottom to avoid

a five foot drop off at the end. He turned successfully

but poor Keeley didn’t see him turn and she went flying.

Man, we scrambled to find her, both of us yelling - our

wives are going to kill us! Keeley was a little shook up but

otherwise okay. Another of those experiences that are

fun in the telling but not so much as they happen.

Rush’s support for my band, FM, continued after the

Moving Pictures tour. I won’t go into details here, but

FM was at a crossroads following the tour and Rush

wanted to help. After a lot of discussion, Neil suggested

that maybe FM should sign with Anthem Records and

Ray Danniels, their manager. Throughout the transition

Neil was supportive but stayed out of things directly. It

turned out to not be a good fit and Ray and FM parted

ways amicably. It was unfortunate but my friendship with

Neil continued unabated.

“It would be so much easier if we were perfect.”

When the invite from Cathy Rich came asking Neil to

sit in with the Buddy Rich Big Band, he asked me to come

down to the studio where he was rehearsing and critique

his prep for the show. When Neil played that show in ’92,

it’s an understatement to say he hadn’t played much jazz.

Maybe a handful of “sessions” outside of Rush.

Watching it and talking to him later about it, I

recognized all the classic jobbing nightmares – unfamiliar

surroundings, the kit too far away from the band, no time

for a good monitor check, if at all, and the worst if you’re

not reading, a different arrangement from the one you

had rehearsed. He said he couldn’t hear the band. Yikes.

But he hung in there. The guy had balls.

Shortly thereafter he introduced me to Freddie Gruber.

Neil invited me out to a dinner with Jackie and Freddie,

while Freddie was in Toronto to teach Neil a series of

lessons. He wanted me to meet his new teacher. Freddie

and I, we hit it off. What a character – the stories! “If half

them are true!” Neil laughed. They would become very

close.

Neil showed me what Freddie was teaching him. “Look

Ma, I’m dancing!” I could hear the change in Neil’s

playing – it was rounder. After a year or so of studying

with Freddie, Rush recorded Test For Echo and I was

in invited to the studio for the final mix. They weren’t

often in Toronto recording so it was a treat to visit and

hang. On commenting on how good he sounded, Neil

turned to me and said, “Yeah, Ged asked me if I had new

cymbals!” We were in tears.

“Hyena says - I am not lucky, but I am always on the

move.” (Kikuyu proverb)

Words cannot express the absolute, excruciating grief

and pain of Selena’s death. When Jackie died ten months

later, we were just so numb. Time stood still. It is hard for

me to say anything about that time. Neil, said he had to

write “Ghost Rider”, but wondered aloud, “How anyone would want to read it.”

We stayed in touch - notes from Freddie’s back yard,

from a hammock in the southern Baja - but there were

long stretches…

As time passed, he reached out more and more and I

could feel his spirit returning. Friends in L.A. helped with

the difficult task of re-entry into whatever the rest of his

life was going to be. It is hard to imagine how vulnerable

he was. Then he met Carrie and allowed himself to fall

in love.

We didn’t know if he would play again. I asked him. He

wasn’t sure. Some time later, he wrote back saying Carrie

had looked at him one day and said, “You’re a drummer,

you should drum.” With baby steps he got back on the

kit and pounded away, pounded his grief, wailing at his

story.

Rush didn’t disappear when Neil needed time to

grieve and get sorted. Their absence made their fans

grow fonder. They came back. They doubled down. Neil

had a publisher in ECW, he was making more videos,

and created a web page full of humor and with “News,

Weather, and Sports”, a blog that was a personal memoir.

He really was A Man with Many Voices.

When Rush played Toronto in support of Vapor Trails,

there was not a dry eye in the place.

The thing about Rush was their integrity. They didn’t

sell out to the man. After the success of 2112 - the album

where they resisted all pressure to conform or be cast

out - they now had ‘f*ck you’ money. They never took

sponsorship. Discussions about photos, caricatures on

lunch boxes? Not a chance. Started their own record

company. Owned their masters. Again and again they

showed us, evidenced by their choices, that they were

coming from the heart, and we loved and respected

them for it.

The thing about Rush was their integrity. They didn’t

sell out to the man. After the success of 2112 - the album

where they resisted all pressure to conform or be cast

out - they now had ‘f*ck you’ money. They never took

sponsorship. Discussions about photos, caricatures on

lunch boxes? Not a chance. Started their own record

company. Owned their masters. Again and again they

showed us, evidenced by their choices, that they were

coming from the heart, and we loved and respected

them for it.

Objectivism had appealed to Neil when he was younger

and Ayn Rand’s writing had influenced his early thinking.

Neil did “live by his own effort,” but as to Rand’s idea

that one “does not give or receive the undeserved,” well,

if he had ever agreed with that philosophy, he certainly

didn’t after Selena’s death. “Who deserves that?” he

remarked.

And then. After he had hung up his skates, after his

amazing career, after everything, his annual birthday

greeting contained the news of his “brain salad surgery”

- I was devastated.

I got out to Santa Monica the following spring. At

dinner he reconciled. “I had a good run,” he said. And

it had been.

An enviable career, an extraordinary 45 years, doing

what he loved at the ultimate level, the way he wanted.

What a life. And now he was fighting the good fight - for

his daughter Olivia, I think. It broke my heart.

I’m thankful we had a chance to say our goodbyes, the

only sliver of silver in an otherwise dark lining of a life

well lived.

Neil never lost the fascination, the real relation, the

underlying dream. I’ve never met a man who was truer

to his word.

You will be missed, my friend, but you are not gone.

ROD MORGENSTEIN

Neil Peart was a Renaissance man. Most of us know him

as the iconic drummer and lyricist of Rush, but beyond

his exceptional talents in the world of music, Neil’s zest

for life, thirst for knowledge, and quest for adventure led

him down many divergent paths.

I had the honor and pleasure of meeting Neil in 1985,

when The Steve Morse Band toured with Rush as their

opening act on the band’s 85/86 Power Windows Tour.

Most touring musicians will attest to the absolute joy and

excitement of bringing their music to audiences around

the globe. Most of these same musicians will also agree

on the physical and emotional toll that endless touring

can take on a human being.

That said, a typical show day often consists of

travel, sound checks, meet and greets, interviews, the

performance, followed by more meet and greets. Well,

as if this is not enough, a typical show day for Neil

Peart on tour would usually begin in the wee hours of

morning, as Neil would journey on his bicycle from the

previous city (assuming said previous city was within

150 miles of the next gig). Neil would often be on his

bike for hours, arriving in time for Rush’s sound check.

Directly after sound check, he would have dinner, which

was immediately followed by a one-hour conversational

French language lesson with a local French-speaking

tutor. Upon completing his French lesson, Neil would

proceed to a private practice room and warm-up on

a small drum kit prior to the band’s two-hour concert.

After the concert, Neil would usually hang for a short

time before excusing himself to go to the band’s tour

bus, to work on one of his future literary creations.

That said, a typical show day often consists of

travel, sound checks, meet and greets, interviews, the

performance, followed by more meet and greets. Well,

as if this is not enough, a typical show day for Neil

Peart on tour would usually begin in the wee hours of

morning, as Neil would journey on his bicycle from the

previous city (assuming said previous city was within

150 miles of the next gig). Neil would often be on his

bike for hours, arriving in time for Rush’s sound check.

Directly after sound check, he would have dinner, which

was immediately followed by a one-hour conversational

French language lesson with a local French-speaking

tutor. Upon completing his French lesson, Neil would

proceed to a private practice room and warm-up on

a small drum kit prior to the band’s two-hour concert.

After the concert, Neil would usually hang for a short

time before excusing himself to go to the band’s tour

bus, to work on one of his future literary creations.

At some point during this same time period, when

he had some time off from touring, Neil flew to China,

where he met up with a handful of bicycling enthusiasts

for a 3-week journey through remote parts of the

country. With pad and pen in hand (at the time, Neil

felt that a camera interfered with the creative process)

he would jot down highlights of the day’s experiences,

which eventually culminated in one of his first literary

works entitled, “Riding The Golden Lion”. In addition

to the writing portion of this 39-page journal/book, Neil

was involved in every step of the process in putting the

book together, including choosing the cover art, font,

page color and thickness, etc. I believe it was the first

outing in what would become a passion of his, eventually

authoring several critically acclaimed books.

On the very last day off of The Steve Morse Band’s

final leg of the Rush Power Windows Tour, Neil, Alex,

and Geddy took our band to an exotic restaurant for a

memorable band dinner. Sitting cross-legged on pillows

on the floor, in our very own private room, sans silverware,

we dined on an incredible feast of delicacies using only

our fingers. Alex, a wine expert and connoisseur, made

sure the nectar of the gods was flowing. So, there I am

sitting next to Neil, chit-chatting while trying to think

of something interesting and stimulating to say to this

sophisticated, worldly, well-traveled man. Neil beat me

to the punch, turning to me and posing the question,

“So Rod, have you ever considered the effects of climate

on the development of Western Civilization?”

That, in a nutshell, sums up the ever-inquisitive Neil

Peart, always seeking knowledge and new experiences,

never happy with the status quo. He is the textbook

definition of ‘Carpe Diem’, seizing every moment of

life to engage in something of importance, be it music,

reading, writing, philosophizing, bicycling, motorcycling,

sailing, cross-country skiing, trekking through foreign

lands, climbing the highest peaks, and devoting himself

to family. He is a truly inspiring human being, whose

breath of humanity has touched millions around the

world.

I am forever grateful to have known this unique and

special man. RIP Neil

PETER ERSKINE

It’s a common enough thing to do...when time or

circumstance brings a friend or loved one to mind,

we search for a tangible element of memory. This was

always in the form of a scrapbook, a photo album or even

a shoebox filled with letters. Of course, nowadays, it’s

the searchable database of an email program that can

bring past digital conversations to life. That “life” word

is very important.

And so, it was after I received the news of Neil Peart’s

passing, I needed to touch something of him. I could watch

some YouTube videos, but any of those performances

were not at the core of our relationship (even though

some of our work together did manifest itself in his later

playing, at least, according to Neil). Tributes galore from

all manner of drummers, but, again, that was not the

basis for our friendship or ensuing correspondences.

Reading the back and forth of our letters, I’m surprised

now by how collegial and even intimate our written talks

turned out to be. This was due to a couple of factors...

And so, it was after I received the news of Neil Peart’s

passing, I needed to touch something of him. I could watch

some YouTube videos, but any of those performances

were not at the core of our relationship (even though

some of our work together did manifest itself in his later

playing, at least, according to Neil). Tributes galore from

all manner of drummers, but, again, that was not the

basis for our friendship or ensuing correspondences.

Reading the back and forth of our letters, I’m surprised

now by how collegial and even intimate our written talks

turned out to be. This was due to a couple of factors...

First, Neil was an incredible writer of words. Each letter

is as carefully constructed as one of his drum solos, and

he enjoyed an ability to be as prolific as he was varied in

his voice on paper. To put it more simply: his letters are

an incredible if bittersweet pleasure to read again. The

comparison that comes to mind is a warm and inviting

bath. The man knew how to turn a phrase. And he was

always a perfect gentleman in his prose, spontaneous or

otherwise.

As tempting as it is to share some of his missives with

the world at large, that would betray his confidence in

me. I’ll just leave it at: the man could write.

Second, he surrendered much more of himself than I

expected him to. I’ve taught other rock drummers who

were coming to me with the vague reason or expectation

that learning a wee bit of jazz would somehow

automatically “up” their game in no time. They were

usually disappointed to discover that these things TAKE

time. Neil had no such illusions. An instructive allegory

can be found in his love of motorcycle riding and his

appreciation for the journey. He found meaning and joy

in the process and in the work. And this guy wasn’t just a

rock star. He was THE drumming rock star.

Meanwhile, I had never even listened yet to a single

song by Rush when we met for the first of several lessons

at my home. (Since Neil spoke openly about our work

together, I can follow suit.) He was an ideal student

of the instrument. And, in that sense alone, he was

very much like his idol Gene Krupa, who sought out

instruction from other drummers and percussionists

while at the height of his own fame and glory. Neil paid

attention and did his homework. He seemed to delight

in keeping me apprised and abreast of his steady stream

of improvement and epiphanies. One of his goals was to

improvise more. My first job as his teacher was to provide

some practical mechanical and musical advice. My

second job was to encourage the fire that was already lit

under his motorcycle seat. Teacher’s delight: he ran far

and wide with the ball, to mix metaphors. To be honest,

I only showed him a couple of things. But I suspect that

the dynamic of the mentor/student relationship was

something he intuited that he needed at that moment.

He was ready to get to his next level, I just helped him to

find the button on that elevator.

Of course, because I was not a fanboy, he could trust

me completely. I know he took delight in giving me my

first Rush album and was quite happy when I told him

how much I liked it. His drumming really impressed me.

Duh. I just got done saying that he was the Gene Krupa

of our time. Allow me to explain...

It was only with time that I was able to fully appreciate

what Gene Krupa did for drumming and for jazz. Gene

was no Chick Webb, no Baby Dodds, no Sid Catlett, no

Papa Jo Jones and no Buddy Rich. I mean, he was no Art

Blakey either (when I was real young, I was crazy about

Art Blakey and Max Roach). But Gene Krupa was, in some

respect, greater than the sum of all of their parts. Gene

Krupa made the drums so popular that it was as if he

had INVENTED drumming. For most folks, Gene Krupa

WAS the drums. Yet, Gene Krupa was innately modest

despite his abilities as a drummer and performer. His

persona at the kit, while it scored a bullseye with most

non-drummers, belied how seriously-well he played. Neil

may have enjoyed or suffered that same misconception

on the part of some drummers. Several million Neil Peart

fans can’t be wrong, however. I never got it until I got it.

As far as I could tell, Neil never considered himself

anything other than a student of the instrument, plus

a guy who went on the road to do his job even if that

meant leaving his wife and daughter at home for

extended periods of time. But I am fully-prepared to join

the chorus of fans who love Neil Peart...I just came to

love him ultimately for different reasons.

Two key words: his humility and his humanity.

Like his original idol Gene Krupa, Neil Peart changed

the world of drumming forever, and we should all

mourn this loss as well as celebrate all of the joy that his

percussive journeys brought us. I think he would prefer

the “joy” part. He reveled on the road less traveled, and

he delivered wherever he went. I’m grateful that we kept

in touch for some of this time and that I have his letters

to hold and cherish. I’ll be printing them out later today

to read by the fire.

STEVE SMITH

Neil Peart and I met in 1985 during the recording session

for bassist Jeff Berlin’s first solo album Champion. The

album was produced by Ronnie Montrose and featured

Scott Henderson on guitar, T Lavitz, Clare Fisher and

Walter Afanasieff on keyboards, with Neal Schon sitting

in on guitar for one song. Jeff had me play drums on

most of the album and asked Neil to guest drum on

two songs. We all knew for Neil to accept that offer

was unusual and we were excited to have him perform

on the record. When Neil arrived at the session, he was

gracious to us all, a true gentleman and humble. He was

also extremely prepared. Neil played on the title track,

“Champion (of the world),” and as I recall, he played a

perfect drum part in one take. He also played on the

Cannonball Adderly tune, “Marabi.” Jeff had devised

an incredible arrangement for this up-tempo swinger.

Neil played a grooving shuffle throughout. It was my job

to come in on the rock bridges, and the outro, playing

a double-bass Billy Cobham-style shuffle, double-drumming

with Neil. The song came out great and we all

had a fantastic time. Everyone was impressed with Neil’s

musicianship and creativity. After the session Neil broke

out his bottle of scotch and we had a lovely time trading

stories and laughing into the evening.

I knew Neil as a man of great humility, intelligence and

humor. His drumming has inspired generations and I’m

sure, will continue to inspire and inform drummers of the

future. He left us far too soon with scarce time to enjoy

his new family and his retirement. I am grateful to have

known Neil Peart. He is already missed.

JOE FRANCO

I actually got to play Neil’s kit in 1979. The Good Rats were doing a Northeast run with Rush on their Hemispheres tour in 1979 and the first show was at Nassau Coliseum, our home turf. Neil was watching our sound check from side stage and afterwards came up to me, introduced himself (needed no introduction) and asked if he could check out my kit AND if I’d like to check out his. We did a short drum-off and it was awesome. Since his passing, I’m totally obsessed with all things Neil and Rush. I didn’t grow up a Rush fan as Neil and I were the same age and started making records around the same time. For me, the 70’s was about Tony, Billy, Alphonse, Lenny and the whole fusion movement. That’s where I went for inspiration, so I wasn’t listening to Rush, Sabbath and a lot of the bands that rockers were into. I liked what Rush was doing and respected the hell out of Neil but never listened in detail… until recently. I was so moved by the amazing tributes that were posted on social media and have since gone back and revisited their body of work. I can’t get enough of YouTubing his interviews and playing. I’ve also picked up a few of his books and am in the middle of reading “Ghost Rider.” What an amazing man. Unequalled in his passion for life. A great loss to us all. RIP Neil Peart.

CHRIS STANKEE

One of the things I admired most about Neil was his

discipline. He worked at his many crafts. Not to be the

best-ever, but the best he could be. He looked for fresh

inspiration through experiences. When he had ridden

all the paved roads, he went off road. When he ran out

of road, he took to the sea. Literally and figuratively. He

read thousands of books to inform his own writing.

When he reached a point in his drumming that he

thought he could benefit from new techniques, he took

lessons. He understood that a good student needs

empathy and humility in addition to talent and discipline.

This made him a master. He was all in- dedicated,

devoted and we should all be as bold as Neil Peart.

DOANE PERRY

During the last three and a half years, Neil faced this

brutal, aggressive brain cancer bravely, philosophically

and with his customary humor, sometimes light and

occasionally dark - all very characteristic of him, even

given the serious situation and the odds handed to him

at the time of the diagnosis and subsequent surgery. But

he fought it. By his own request for privacy, few people

knew, but his understandable response to this news in

no way excludes or diminishes ALL of those who also

knew him, worked with him or loved and admired him

from up close, or at a distance. His tenacious approach

to life served him well during these last years and

although he primarily kept his own counsel, he retained

his dignity, compassion, understanding and his deeply

inquisitive nature, which never deserted him. Remarkably,

considering the severity of his condition (glioblastoma)

and through the resulting aftermath, he really had no

pain. This was always my first question when I saw him.

“Any pain?” I asked.

“No pain”, came the reply.

What a blessing that was. We were all grateful for that.

For every one of us who loved him, near and far, this

is a loss that is difficult and impossible to summarize in

a few short paragraphs. The outpouring of love, respect

and appreciation from every imaginable quarter for this

extraordinary, singular talent and beautiful man with a

mind like no one I have ever met, is touching beyond

words. To those that had to guard and hold on to this

information closely for three and a half years, for obvious

and protective reasons; his wife Carrie, daughter Olivia,

his loving family, band, colleagues and friends, they have

my undying admiration. You know who you are.

Apart from his deeply gifted, genius talent and prolific

output, which he brilliantly displayed through music,

lyric and prose writing and that staggering storehouse

of knowledge across an array of subjects in multiple

fields, he remained a kind, gentle, considerate and

modest soul and a consummate gentleman… as well as

an extraordinary friend. If you were his friend, you knew

it and he understood how to be the best friend that you

could ever hope to have. I think I speak for all, known

and unknown to him, to say he will be deeply missed,

eternally loved, appreciated and remembered for his

many invaluable contributions to music, art and the

written word. That will be forever celebrated.

Despite what he knew and we knew which was

inevitable, I believe there is some sense of relief that this

long, difficult odyssey has finally ended.

Thank you, my dear friend, for passing this way. We are

all richer for your presence and light in our lives.

JASON BITTNER

To describe just what Neil Peart means to me would

take an entire issue so I will attempt to keep this brief.

I first met Neil in June of 2007 through my friends Rob

Wallis, Paul Siegel, and Joe Bergamini from Hudson

Music, along with the help of my then-new, NAMM 2007

buddy, Lorne Wheaton. I had just finished up my Hudson

DVD and asked Paul if he may be in town for my local

RUSH show and, “Would there be ANY WAY POSSIBLE

to meet The Professor?” Yes, I know, he doesn’t really do

the meet-and-greet thing, but I figured I had an “in” of

sorts. He said, “All I can do is ask,” and that was good

enough for me. Meanwhile, I had already met and hung

with Lorne at a Promark party at NAMM 2007 where he

repeatedly told me, “Just text me and I’ll get you in,”

along with, “Oh, don’t worry, Neil knows who you are.”

Are you kidding me?! I really just thought Lorne was

being nice to me and there was no way that I was on

Neil’s radar, even though I had heard the same from Nick

Raskulinecz who was working on the Vapor Trails demos

with the band, while he was also working on one of my

records. Anyway, I still didn’t believe them.

At around 3:00 the day of the show, Paul calls me and

goes, “How soon can you get up here?” I said, “Forty

minutes. Why?” He then says, “Neil has agreed to meet

with you!” My wife then hung up the phone, since I had

had a heart attack by that point, and we raced up to

Saratoga.

At around 3:00 the day of the show, Paul calls me and

goes, “How soon can you get up here?” I said, “Forty

minutes. Why?” He then says, “Neil has agreed to meet

with you!” My wife then hung up the phone, since I had

had a heart attack by that point, and we raced up to

Saratoga.

The next 40 minutes was complete “Holy shit, this is

happening” mode. My good friend Mike Portnoy texted

me with one very important piece of info, that I already

knew from years of knowing about NP: Do NOT talk

about drums unless HE brings it up. A wise thought

indeed… And yes, he did start talking about drums. As I

waited backstage with my wife for his arrival, I finally saw

the man walk by, and it literally took my breath away–I

indeed just saw God. Of course, I would never tell him

that, and never, in all the times I talked with him, did I

say, “OMG you’re my favorite drummer.” I didn’t have to.

As we entered the room, Michael, Bubba’s right-hand

man, said to my wife, who was holding my camera, “No

pictures.” I thought, “Uhhhh, I don’t think so. If I’m finally

going to meet him, I will ask him and chance getting

shot down, but I’m at least asking, especially if I never

have another chance to talk to or see him.” He then took

the next 20 minutes of his warm-up time–you drummers

know how important that is–and chatted about our

shared producer “Boosh;” he also showed me what he

had been working on in his lessons with Peter Erskine–

I’m realizing right now as I type this with a wet keyboard,

not only did he talk about drums with me, but he gave

me a five-minute lesson too…priceless…I need a second

here…

Okay, so before we left, he signed my Slingerland Artist

Snare. “I had one just like this,” he says, “Yes sir, I know.”

I then asked, “Neil, would it be okay to take a picture?”

and he said in that bellowing Bubba voice, “Suuurrreee.”

I think I may have casually smirked at Michael as I handed

Paul the camera...ha ha, told ya! It’s all jokes–Michael is

my buddy now, and he was just doing his job, but there

was no way I was leaving without proof this actually

happened! At this point, he took a pic with my wife

and I together, so my wife says, “Neil, would you mind

just taking one more with only him, because he’s been

waiting his whole life to meet you!” And he looks at her

and goes, “Of course, we wouldn’t want that first one

to end up in a settlement one day!” The whole room,

us included, broke out in hysterical laughter, it was so

quick and so perfect for my first-ever meeting with him–

signing my/his drum, giving me a lesson, and cracking

jokes…I still can’t believe it, it was amazing. And that’s

exactly what I told Mike, when I texted him after I left the

dressing room, “Holy shit bro, it was amazing!”

For the next tour and every single one thereafter, I was

on his guest list every time I could make a show, and even

when I was on tour myself and missed a few, he would

still put my wife or my other family members on and give

them great seats. Then on the farewell tour, when I said

“I think I’m coming to more than one show, but I don’t

expect entrance to all of them” I got, “No problem, just

let us know when.” That’s the kind of guy he was. I was

lucky enough to meet with him a few more times over

the years, with more great stories, and even when he

didn’t have time to get to see me backstage, I always got

the email, “Sorry I won’t be able to meet today, but your

tickets and passes will be there, all the best, and I hope

you enjoy the show!”

Until the day I can finally tell you, “You’re my favorite

drummer!”

RIP Neil, Bubba, The Professor

COREY MANSKE

Every one of us has a few favorite drummers and some

of us can boil it down to just one. It’s a common dialogue

here in our drumming community and I’ve proudly

offered, “I’m a Neil guy” since day one of my journey.

For me, Neil Peart was nothing short of a superhero. He

harnessed everything I aspired to be as a drummer, as a

bandmate, as a writer, and as an individual. In 1991, I was

an eighteen year old college freshman in my very first

night away from home after my parents dropped me off

at my dorm. As a percussion scholarship student, I had

to report a week early for band camp so the residence

hall was mostly empty. I started to set up my half of the

room and I began to cry because I was all alone. I was

scared and instantly homesick. Self-doubt crept in and I

wondered what I was doing at this university two hours

from home. In an attempt to shake it off, I did what any

music fan would do: I hooked up my stereo, popped

in a CD, and cranked it up so I could start hanging my

favorite band posters. The CD was Rush Hold Your Fire

and the first poster–which I still have–was an all red Hold

Your Fire tour poster with an individual photo of each

member beside each of the three red spheres.

I stared

at the poster, wiping tears from my cheeks as the fifth

track played. “The point of the journey is not to arrive.

Anything can happen.” In that moment Neil’s lyrics

blossomed in my mind, made me believe I was in the

right place, and enabled me to continue on my path–one

that I’m still on nearly thirty years later. His musicality,

creativity, passion, technical prowess, skill, and attention

to detail have always, and will always, inspire me as a

drummer. Each of those attributes is important to me,

but there is one more which tops them all: an endless

dedication to honing his craft. Using his vast drumming

vocabulary, with each record Neil always had something

new to say and I will forever be grateful that he said so

much to me.

JEFF BERLIN

Going back many years... Rush used to come and watch

Bill Bruford’s band play, because for that brief period

in music history, we were a very big thing. The Bruford

band was a “player’s group” and in that particular time in

history, players were admired just for playing well. I was

very fortunate, as was Neil, to have been recognized for

that; we appeared in a window of time where the mere

demonstration of skills at a high level was appreciated by

a lot of people. It was through that, that Neil and I met. I

don’t remember exactly how, where or when, I just recall

meeting this very nice man who played in a Canadian

rock band that everybody loved. Eventually I heard the

records and thought, “Yeah, these guys are great” and

became a fan.

When I did my record Champion, it was 1985 and an

early part in my life where my involvement with Neil

could have been at a higher level. Meaning, that if I had

collaborated with him recently, I’m certain that I would

have worked with Neil in an entirely different level of

musical interaction. Back at that time, I was transcribing

a lot of great solos from artists that weren’t bassists. Neil

was such a powerful rock drummer, and I had this heavy,

hard-hitting arrangement of Cannonball Adderley’s

“Marabi,” so I invited Steve Smith, who was playing with

Journey at the time, and Neil to double drum on it. It

came out fantastic. It was so powerful that when I heard it

back in the studio, I wish I had done four more choruses,

just to have more of them playing. Again, I was a young

guy and wasn’t thinking about arrangements in the way

that I would be today.

When I did my record Champion, it was 1985 and an

early part in my life where my involvement with Neil

could have been at a higher level. Meaning, that if I had

collaborated with him recently, I’m certain that I would

have worked with Neil in an entirely different level of

musical interaction. Back at that time, I was transcribing

a lot of great solos from artists that weren’t bassists. Neil

was such a powerful rock drummer, and I had this heavy,

hard-hitting arrangement of Cannonball Adderley’s

“Marabi,” so I invited Steve Smith, who was playing with

Journey at the time, and Neil to double drum on it. It

came out fantastic. It was so powerful that when I heard it

back in the studio, I wish I had done four more choruses,

just to have more of them playing. Again, I was a young

guy and wasn’t thinking about arrangements in the way

that I would be today.

With regard to working with him, I simply asked

if he wanted to come and play and he said, “Sure, I’d

love to be a part of the record.” He was totally open to

anything that I wanted to do with him. To prepare for

the recording, I recall sending him demos, and then we

rehearsed somewhat before we recorded. I wish I had

taken pictures back then, but I didn’t. Neil’s drum set was

a double bass, with a snare, two toms, two floors and a

few cymbals. Even though Neil was known for playing

this monstrous kit, it was the music that came first, so his

usual setup wasn’t necessary. For the recording, Neil was

facing Steve and they played together for what I called

The G Section, because it was in G. But what I discovered

was, when they played that section together, their bass

drums were playing triplets that were just unrelenting–it

was too much. I had to decide to simplify it a bit between

the two of them and what ended up working was Neil

played his triplet figure with a cymbal downbeat, then

one bass drum and then the other bass drum, then a

snare downbeat and one bass drum and then the other

bass drum. So, for the triplet figure, Neil was playing

cymbal-bass drum-bass drum, snare-bass drum-bass

drum. Steve then played a shuffle with the two bass

drums and between the two of them, we got a full triplet

double-bass drum pattern playing every note.

For the other song Neil played on, “Champion (Of

The World).” I’m tempted to go back in and do it again–

isolate the original drums, but this time, record and

mix it to today’s standards, with the rock vibe that I had

originally had in mind.

Neil and I had a quarter note together; we could play

together and didn’t have to think about anything else–

that’s why I did the Buddy Rich Big Band with him. We

instantly found a musical kismet between us, as well a

socially understandable manner of life–we were the

same age and amongst other things, had a common

admiration for Cream, with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker.

We were a couple of knuckleheads and just clicked. He

would send me the books that he’d written, or send me

emails with stories about life, and he’d also send me

demos to listen to as well. We clicked as people and

clicked as musicians; you can only click with someone

musically if you have an agreed upon attitude about the

music. If we agree on the quarter note, I’m going to play

great with them and they’re going to play great with me–

we had that. Our musical collaboration, ironically, wasn’t

the outstanding feature of our relationship, it was our

friendship. We hung more than we played. We talked

a lot, sent emails, had pet names for each other...not

to be revealed here, but for 35 years, the guys in Rush

never called me Jeff and I never called them Neil, Alex

or Geddy. So, my relationship with Neil was really more a

friendship than anything.

He was a natural in what Ginger Baker called, “Time”.

And it wasn’t about the astonishing drum set; I could

have and would have loved to have played with Neil on

a four- or five-piece kit. Music was very important to Neil

and what I mean is, it counted equal to or even more

so than his status. He was always evolving and forever in

flux, playing different setups and eventually, even taking

drum lessons later on in his career. The number one rock

drummer on the planet, at the height of his fame and

he chose to continue studying, first with Freddie Gruber

and then with Peter Erskine. That’s such an admirable

quality, and something we shared, because I still study

myself. We had so many things that we shared as people,

but it was a friendship above and beyond music.

I remember one time, he invited me up to his house,

which was out in the Canadian woods. It was winter time,

with lots of snow, and he went up on a ladder to hang

Christmas lights. I snuck up behind him, grabbed him

and we both went flying into the snow, laughing–that’s

what I miss the most.

JOHN GOOD

Neil and I had a great relationship because we both

admired each other and the things that we did. And to

be absolutely honest, I couldn’t say that I was a big Rush

fan, but I can honestly say that I was a big Neil Peart fan.

Neil came to me and said, “I really dig what you do.

I’ve seen a few things online...”–he had done a bit of

homework–and he actually helped me take a lot of the

things that I was talking about trying to accomplish and

trying to put out to the rest of the world; things that I

felt were important for drummers to understand–how

to tune their drums and where I was going with making

drums.

We had many discussions about making drums, and

eventually he started calling me The Wood Whisperer.

As time went by, year after year, we got closer and

closer to being like family–he felt very close to DW and

spent a lot of time with myself and Don [Lombardi], and

especially Don due to Neil using the Drum Channel

facility as a rehearsal place. We spent really good quality

time together, talking about the philosophy of drums–

he was a great philosopher–and from that, I asked him

one day, if he would write the forward for my book, “The

Book Of Plies,” to which he informed me that he was

in the midst of writing another book, but he would see

what he could do. I thought, “Okay, I better just leave

him alone.” Twenty minutes later, he sent this forward,

that would have taken any mortal man a year to write, let

alone even imagine those thoughts.

One of the really great things about our relationship

was that I could actually bounce things off him and he

was totally game for most everything I wanted to do.

For example, he was the first guy who wanted to try my

idea of a 23-inch bass drum. So, I made one and sent it

to Toronto, and Lorne Wheaton, Neil’s drum tech, slid

it underneath him. He played it and said, “Now I can’t

live without this.” He then started playing only 23-inch

bass drums and for a lot of the followers of him and his

work, they started to play 23-inch bass drums too, which

was gratifying for me because that’s my favorite size bass

drum–they’re just beautiful.

One of the really great things about our relationship

was that I could actually bounce things off him and he

was totally game for most everything I wanted to do.

For example, he was the first guy who wanted to try my

idea of a 23-inch bass drum. So, I made one and sent it

to Toronto, and Lorne Wheaton, Neil’s drum tech, slid

it underneath him. He played it and said, “Now I can’t

live without this.” He then started playing only 23-inch

bass drums and for a lot of the followers of him and his

work, they started to play 23-inch bass drums too, which

was gratifying for me because that’s my favorite size bass

drum–they’re just beautiful.

We often would discuss sonically, the sound(s) that he

was looking for and what he wanted to achieve. After we

would speak, he would then go over to see Louis Garcia

and they would discuss the fantastic visual designs, that

I must say, I’m so proud of my crew for being able to

pull off. And each new tour became more epic than the

previous one, so it was one of those situations where

all of us here wanted to be a part of what Neil wanted

the world to know and realize–and not just for himself,

but also for my company and for what Neil was really all

about in the world of drumming.

Anyway, time goes by, we do some things together

video-wise and we’re now feeling really comfortable with

each other. He would always come and rehearse at DW

for about three weeks before every rush tour. Lorne would

show up and they’d work together on the whole blown-out

kit, the riser, everything. Then an eighteen-wheeler

would arrive, and they’d pack up the whole thing and off

it would go to Toronto, where they’d rehearse as a band

for their next tour. Seeing that, I admired the fact that

he loved the routine. He’d drive his Aston Martin in from

Santa Monica, and we’d wind up at the Drum Channel,

and then go off to lunch when he’d say, “Let’s go have

a ‘three Arnold Palmer lunch’ at the Olive Garden”–he

loved the simplicity of life. As much as I would love to say

he was not a complicated man–because he really was–

he really appreciated the simple, wholesome and good

things of every day.

As time went by, I found that after the last couple of

tours, which weren’t really that long-lasting, he said he

really didn’t want to do that anymore; he wanted to be

around for his family–he’d given forty years of his life to

the road. He had a great way of putting it by saying, “I

think I gave at the office.” But for this last tour, he agreed

to thirty-five shows, and of course, for a production of

that size, it takes probably thirty shows to even start to

earn money back, but they did it, and it came off great.

There’s a DVD of it, which I haven’t had the guts to watch

yet, but as that all ended, he just wanted to retire. He

had a place that he called his Man Cave, which was this

room full of cars, where we would go every now and then

to hang out.

I knew for the last two and half years, what was going

on–that he had some serious health issues–and we all

agreed to keep it very close to the vest, because that

would have been a media frenzy that no one wanted to

bear. And it was tough to shoulder that, through some

dark times, because you really cared about this man–

all you wanted was for it to get better, and it didn’t get

better; it just got worse.

It was just before last Thanksgiving that I wrote him

an email. He had been responding less and less, but he

wrote me back and asked if I wanted to come visit. So,

Don and I went together and met Neil at the Man Cave.

Neil was moving slow, shuffling around a bit, not really

walking around too much. Words were coming slow and

he couldn’t really write much anymore. We sat down and

talked for a while and he said, “I’m not in pain guys, I’m

okay.” When it was lunch time, Don offered to go across

the street to get us some food, so I was there alone with

Neil and asked, “Is there anything you want? Anything

at all.” He said, “No, nothing at all.” So, I said, “Well, I

want to do something. I want to take your R40 kit and

put it in our showroom, behind plexiglass, where people

can come in and check it out.” He just smiled and said,

“That’s what I want.” He then said, “I have my driver that

takes me from my house to the Man Cave every day,

and on the way to, I listen to three songs. Then when

he picks me up to go home, I listen to three more.” I

said, “Really? What songs?” Neil said, “Rush songs!”

Then he said, “I spent a life time concentrating on my

parts. All I could think about was my parts, rehearsing my

parts, and trying to be the best possible drummer that I

could be for that music. But I never really listened to the

embodiment of the music as a whole.” He took a minute

as I was taking that in, and then he said, “You know John,

we were pretty good.”

As we finished our lunch, we got up to leave and give

him a hug–and when you hug Neil Peart, you’re hugging

a man of great stature–I said, “I hope I see you again

soon,” and as I turned to walk away, he grabbed my

hand, and just gave me a long stare, and a smile.

Purchase this issue by following this LINK

-| Click HERE for more Rush Biographies and Articles |-