|

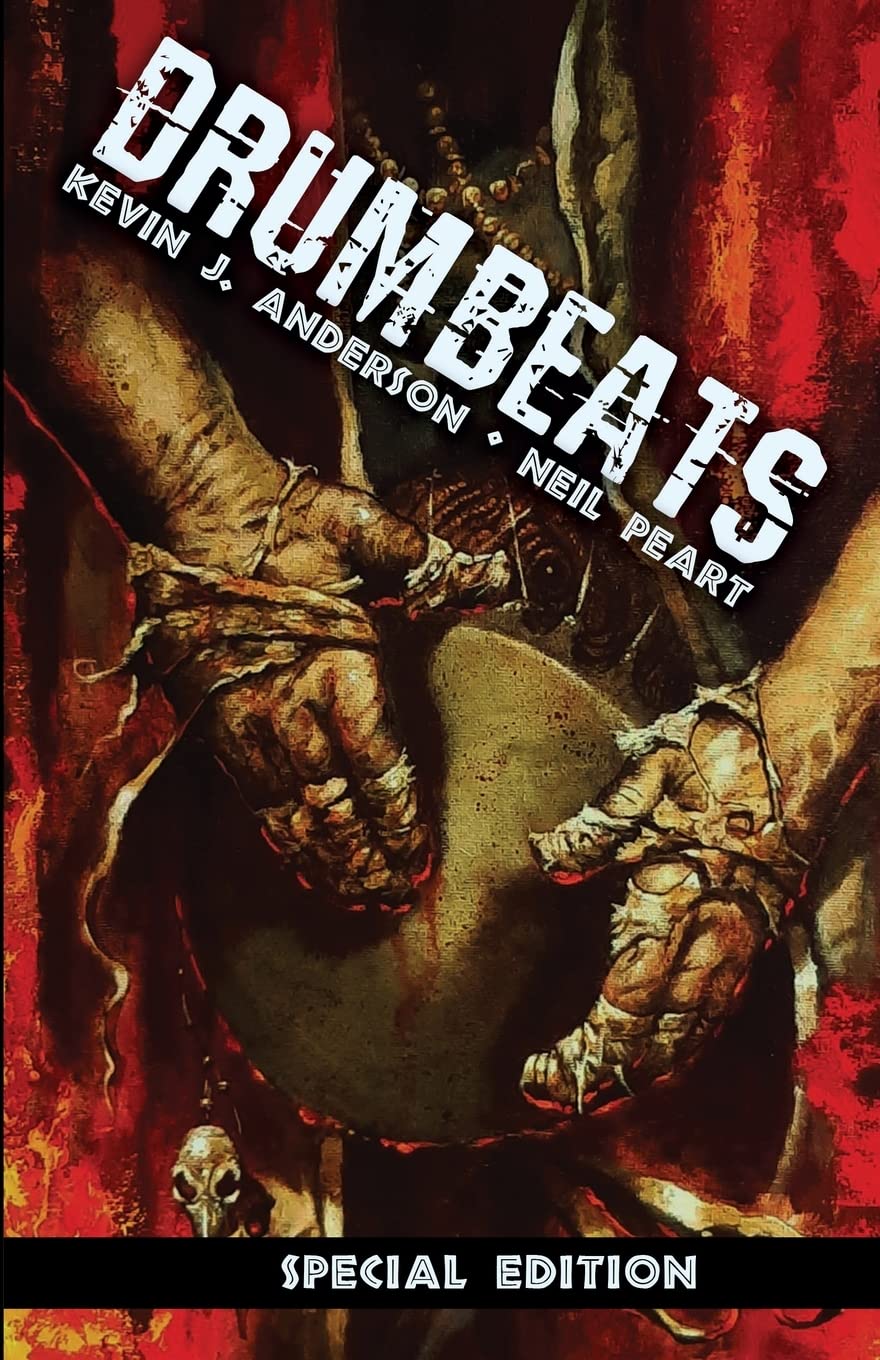

Special Edition by Kevin J. Anderson and Neil Peart Artwork by Steve Otis September 30th, 2020 |

Foreword: Mystic Rhythms — Kevin J. Anderson

Drumbeats

Afterword: Stories to Fire My Imagination — Neil Peart

About the Authors

About the Artist

Acknowledgments

FOREWORD: MYSTIC RHYTHMS

KEVIN J. ANDERSON

The letter came on a bad day.

I was working as a technical writer for the Lawrence

Livermore National Laboratory, where I produced

respirator safety manuals and chemical protective

clothing handbooks. I had to deal with DOE

regulations, editing the commas in health and safety

codes, going to meetings, compiling annual reports,

and delivering rush presentations.

I had always dreamed of becoming an author, but

this wasn’t what I’d had in mind. At least I spent my

evenings and weekends working on my novels.

The real-world tech-editor job offered plenty of

challenges, problems, and chances to screw up. On

that particular day I had been hit from several sides:

An important annual report, produced by me, was

released to great fanfare … and somehow the author’s

name was misspelled on the title page. Also, I had put

together a very important rush presentation on laser

technology, while the anxious researcher was waiting

to race off to Washington, DC to beg for continued

funding; but when the slides came out of the photo

lab, somehow the techs had printed all the photos

upside down, and there was no time to fix it.

The biggest blow came from another direction.

This was the day that one of the largest and most important

magazines in my field, Asimov’s Science Fiction,

ran a review of my second novel, Gamearth. It was my

first major review in a national market, distributed to

all my professional peers … and the reviewer tore me

to shreds.

So, it was not a good day.

Sullen, I came home to my little townhouse in

Livermore, California. I was just a single guy hoping

to make a living as a writer someday. I’d published

a handful of short stories and two paperback novels

for minor advances, but nobody knew my name.

Bummed, I got the mail, sorted through the bills, the

grocery flyers, the junk mail.

And I found an envelope with a Canadian stamp.

The return address said N. Peart.

My heart skipped a beat. It couldn’t possibly …

I opened the letter to find a three-page single-

spaced letter from Neil Peart, legendary drummer

and lyricist for the rock band Rush. A man whose

work I had admired since my high school days. He

had written to tell me how much he loved my first

novel, Resurrection, Inc.

It was no longer a bad day.

Now, this wasn’t entirely a coincidence. My novel,

published by Signet Books in 1988, had been greatly

inspired by the Rush album Grace Under Pressure

[1984]. When I received my first author copies of the

garish paperback with a hideous-looking cover (complete

with stone skull and rocket ship), I autographed  copies to the three members of Rush, acknowledging

their influence on the work, and mailed the package off

to Mercury Records, where I assumed the envelope just went into a warehouse similar to where the Ark of the Covenant is stored. Since so much time had passed, I’d forgotten about it and no longer expected any response.

copies to the three members of Rush, acknowledging

their influence on the work, and mailed the package off

to Mercury Records, where I assumed the envelope just went into a warehouse similar to where the Ark of the Covenant is stored. Since so much time had passed, I’d forgotten about it and no longer expected any response.

In the letter, Neil wrote, “It has taken a year, but

at last I can write to you and tell you that your book

did indeed make it to me. Yes—I might have written

earlier with that information, but now, finally, I can

also say that I have read it. Just as you could only hope

that your message would make it through all the intermediary

barriers to me, so too do I hope that this

delinquent response will actually make it to you.”

Well, it did, and it made my day.

“I have finally read it. Just finished it last night.

And more importantly, I thought it was very, very

good. More about that later …”

As a science fiction nerd, I have been attracted to Rush

music since my teenage years with their epic fantasy

songs, science fiction dystopias, space adventures—

the lyrics were all so fundamentally different from the

usual “Ooh baby baby” pablum on the radio. I was a

skinny kid with a bad haircut, thick glasses, and handme-

down clothes. I had no experience with girlfriends,

so love songs did not resonate, but I did read a lot of

books. And Rush music spoke to me.

Grace Under Pressure came at exactly the right

time, when I was developing my first novel, and the

lyrics fired my imagination. I wrote Resurrection,

Inc. with the album playing over and over, and the

images conjured by the songs made their way into

the story.

When the paperback was published, I wrote a

dedication, right up front, “To Neal Peart, Geddy Lee,

and Alex Lifeson of RUSH, whose haunting album

Grace Under Pressure inspired much of this novel.”

(Yes, shudder, I actually misspelled Neil’s name.)

Neil wrote, “Regarding your dedication to the

humble members of Rush, needless to say I am pleased

and flattered by it, but I think you do yourself a disservice

by saying that your work was even partly inspired

by the songs of Grace Under Pressure. (Though since I

consider that to be one of our most underappreciated

albums, I am glad to see it get some attention, however

undeserved. And your description of it as ‘haunting’ is

one of the highest compliments, in my view, that can

be attached to a work of art.)

“I loved the echoes of ‘Red Sector A’ and ‘The

Enemy Within’ which you wove into your story, but

apart from that you have gone so far beyond anything

I have experienced in lyrics that the dedication

seems unmerited.

“Never mind—it’s still a very nice thing, and I’m

proud of it.”

Best of all, at the bottom of the letter, he added a

little P.S. that I took to heart.

Neil and I began corresponding, and we immediately

clicked. This was in the days before quick email exchanges—

no, Neil and I wrote full-on letters, many

pages long, each one an epic missive. I once teased him

for going on at “Peartian lengths,” an adjective that he

took to heart and repeated in other correspondence.

I loved to hike. He loved to bicycle long distance.

I would describe for him my mountain trips,

my expeditions in Death Valley. I sent him a photo

from the summit of Telescope Peak in Death Valley,

a magical place with a unique perspective. In one direction,

you can see Badwater Basin, the lowest point

in the continental US (279 feet below sea level), and

in another direction you can see Mount Whitney

(14,505 ft), the highest point in the continental US.

(Much later, after many personal tragedies, Neil went

to Telescope Peak himself and used that metaphor in

his lyrics for the song “Ghost Rider”—“from the lowest

low to the highest high.”)

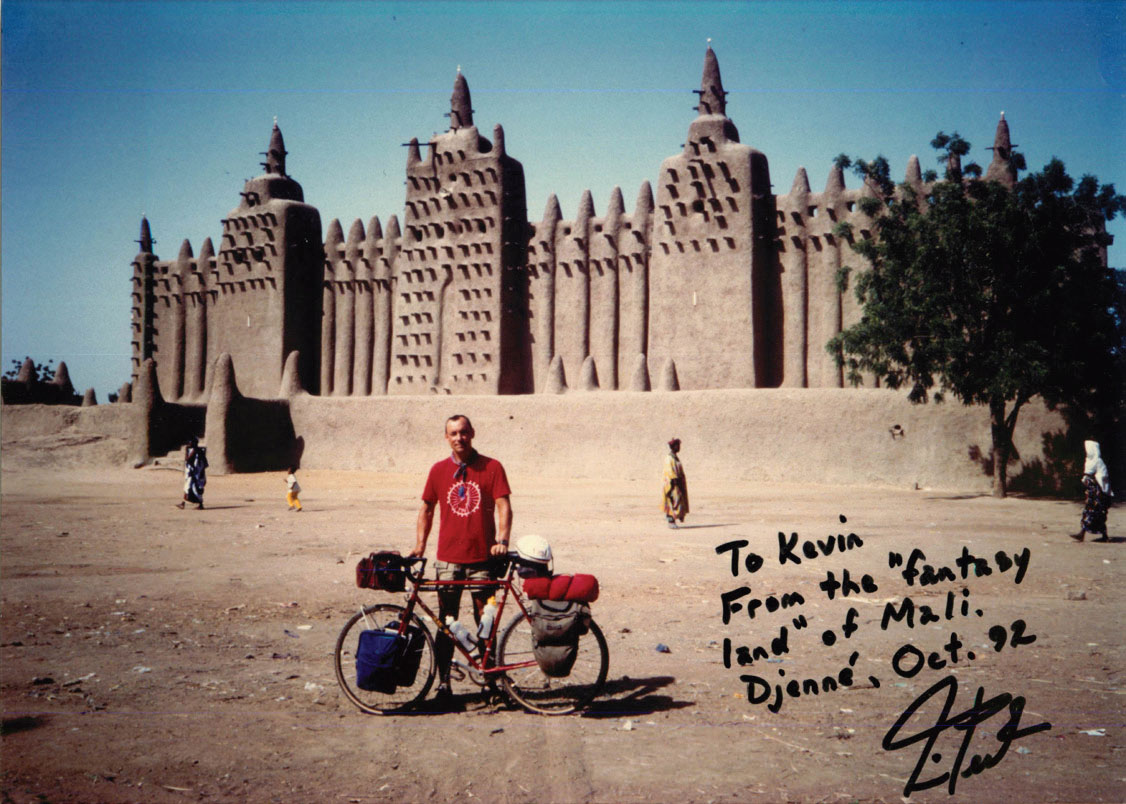

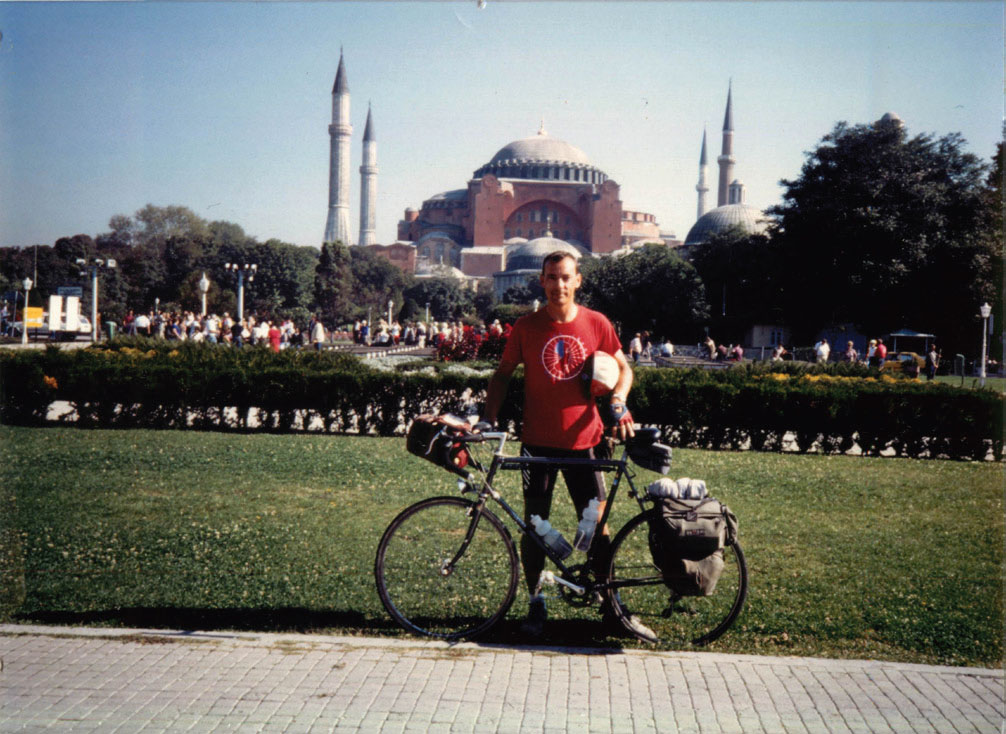

Neil himself took several amazing trips, and

they seem unbelievable to me now. He would

depart for Africa with his bicycle and go off by

himself on dirt roads through the wildest country

and the poorest villages, trying to speak the

language, communicating with smiles and hand

gestures, sometimes talking his way through

armed guards at checkpoints. There he was, a

famous rock drummer on a bicycle, just experiencing

Africa.

“During the past few years, I have become increasingly

interested in prose writing myself, and have been

slowly trying to ‘train’ myself in the art of expressing

thoughts and feelings in ‘good’ writing. Nothing so

ambitious as your undertaking; so far I have limited

myself to attempting to describe some of my travels; to

put into words the experiences and impressions of my

adventures in China, Africa, and on different cycling

expeditions. Not aiming for publication as yet, but

simply as exercises, as good training ground for learning

how to use words. My apprenticeship, as it were.”

And what an apprenticeship!

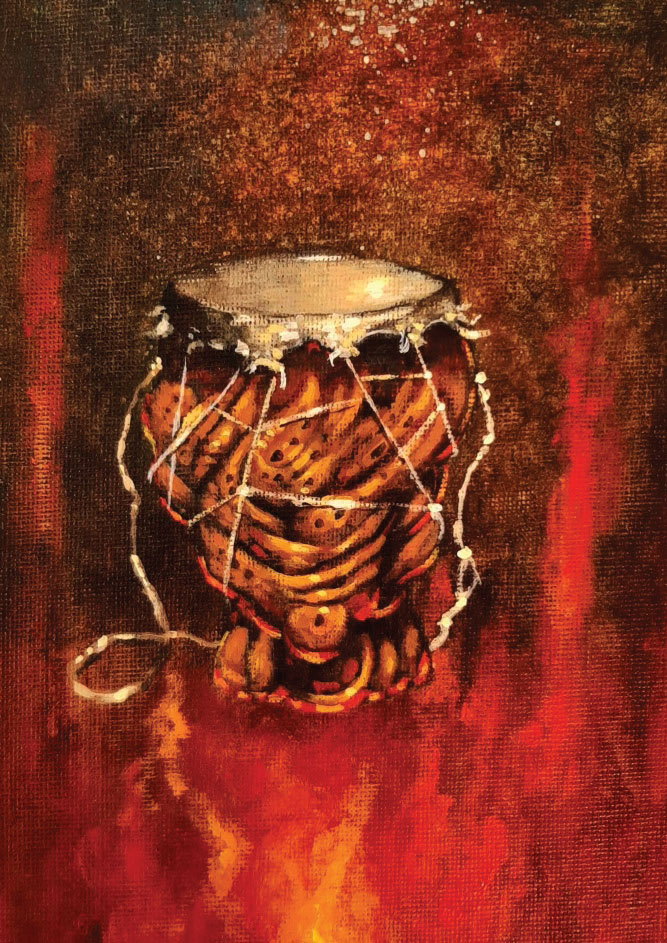

His descriptions were incredible. He went on for

paragraphs about African villages he had visited, people

he had met, adventures he’d had, and a unique African

drum he had purchased from a village artisan. As

part of one expedition he’d even climbed Mount Kilimanjaro,

chronicling the grueling days-long hike from

sea level all the way up to 19,308 feet. He mocked the

tourist brochure that blithely claimed, “Any reasonably

healthy adult can do it.”

Eventually, Neil put together his experiences

around the Kilimanjaro climb in a little self-published

book, The African Drum. I helped him with some layout

advice, which was what I did in my day job for

the Livermore Lab, and he printed up a small number

of copies for friends and family. (The African Drum

remains one of my most precious treasures.)

Off and on, Neil and I had mused about collaborating

on something, possibly lyrics (but I am by no

means a poet), though we never found a realistic project

that worked for both of us.

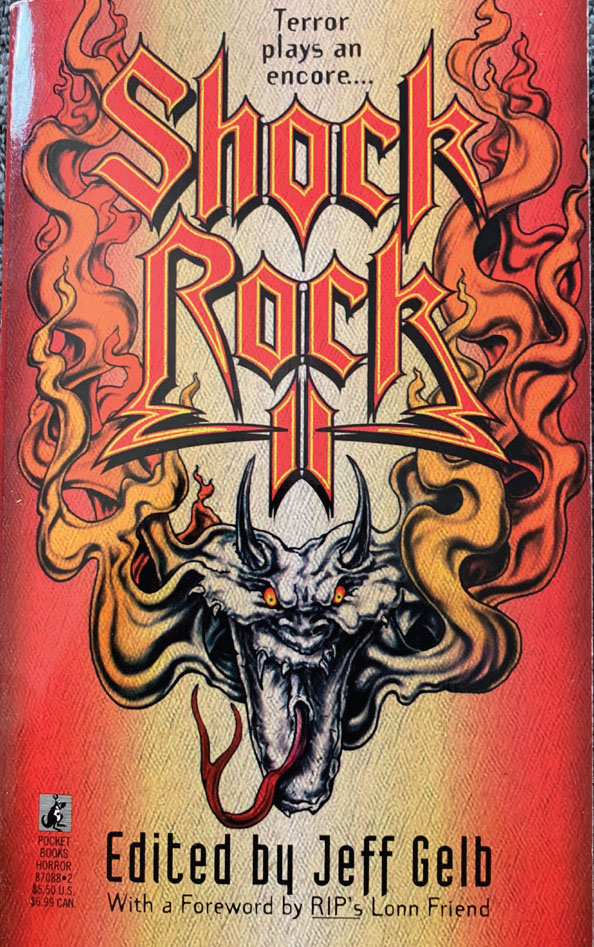

Then in 1993, editor Jeff Gelb invited me to contribute

a story to an anthology he was putting together,

Shock Rock II—horror/dark fantasy stories with a

rock music theme. I immediately thought of a creepy

adventure modeled on Neil’s experiences in isolated

Africa and some of the strange villages he had encountered.

Hmmm, I could pull generously from the descriptions

and landscapes that Neil written about his

real travels, vivid and colorful details that I would never

be able to pull off on my own. I suggested to Neil

that I would write the actual story with a setting painted

from his words, and we’d call it a collaboration. He

was excited by the idea, and when I asked Jeff Gelb if

he would like a story coauthored with the drummer

from Rush, he responded with a dubious letter asking

me to prove that I really knew Neil Peart (!).

I worked on the draft of “Drumbeats,” developing

the plotline and the characters, which was my forte,

and layering in the rich, sensory details of the setting,

which was Neil’s forte. Neil enjoyed working over the

draft and sending it back to me.

Shock Rock II was published by Pocket Books

in 1994, and when I sent Neil his half of the $250

payment (a very reasonable professional rate), he responded

jokingly, “I guess I won’t quit drumming

anytime soon.”

And I’m glad he didn’t. Neil invited me backstage

to every Rush concert tour since 1990.

The response to “Drumbeats” was very favorable, and the

story was reprinted several times. In 2005, I asked Neil

to write the introduction to one of my collections, Landscapes,

and he graciously agreed, but our greatest collaboration

began in 2011, when he asked for my brainstorming

help for a new concept album he was developing, a

steampunk fantasy adventure, Clockwork Angels.

Our novel version of Clockwork Angels became a New

York Times bestseller and won the Scribe Award. We wrote

a second novel in that universe, Clockwork Lives, which

won the Colorado Book Award and (even more meaningful

to me) Neil deemed it, “surely your finest work.”

Many fans kept asking about our story “Drumbeats”

and scoured used bookstores for Shock Rock II or other

places where the story had been reprinted. We decided to

put it up as an e-story, with a new Afterword by Neil. That

version was available for those who just wanted the text.

For years we talked about releasing an expanded, illustrated

print edition, convinced that we would always “get

around to it.” We also did a lot of development work on a

third Clockwork novel, Clockwork Destiny, which remains

unfinished. Each time we saw each other, we talked about

the third novel, but it was never to be, at least not in Neil’s

lifetime … and we both knew it.

The Clockwork Angels album, which Classic Rock

magazine dubbed the greatest rock album of the decade,

was the last studio album from Rush.

Neil Peart died after a long battle with brain cancer

on January 7, 2020. He was my coauthor on two

novels, two graphic novels, and this short story. He

was my friend for more than thirty years. And he was,

and is, my inspiration for most of my life.

—Kevin J. Anderson

DRUMBEATS

(excerpt)

After nine months of touring across North

America—with hotel suites and elaborate dinners and

clean sheets every day—it felt good to be hot and dirty,

muscles straining not for the benefit of any screaming

audience, but just to get to the next village up

the dusty road, where none of the natives recognized

Danny Imbro or knew his name. To them, he was just

another White Man, an exotic object of awe for little

children, a target of scorn for drunken soldiers at border

checkpoints.

After nine months of touring across North

America—with hotel suites and elaborate dinners and

clean sheets every day—it felt good to be hot and dirty,

muscles straining not for the benefit of any screaming

audience, but just to get to the next village up

the dusty road, where none of the natives recognized

Danny Imbro or knew his name. To them, he was just

another White Man, an exotic object of awe for little

children, a target of scorn for drunken soldiers at border

checkpoints.

Bicycling through Africa was about the furthest

thing from a rock concert tour that Danny

could imagine—which was why he did it, after promoting

the latest Blitzkrieg album and performing

each song until the tracks were worn smooth in his

head. This cleared his mind, gave him a sense of

balance, perspective.

The other members of Blitzkrieg did their own

thing during the group’s break months. Phil, whom

they called the “music machine” because he couldn’t

stop writing music, spent his relaxation time cranking

out film scores for Hollywood; Reggie caught up on his

reading, soaking up grocery bags full of political thrillers

and mysteries; Shane turned into a vegetable on

Maui. But Danny Imbro took his expensive-but-battered

bicycle and bummed around West Africa. The

others thought it strangely appropriate that the band’s

drummer would go off hunting for tribal rhythms.

Late in the afternoon on the sixth day of his ride

through Cameroon, Danny stopped in a large open

market and bus depot in the town of Garoua. The

marketplace was a line of mud-brick kiosks and chophouses,

the air filled with the smell of baked dust and

stones, hot oil and frying beignets. Abandoned cars

squatted by the roadside, stripped clean but unblemished

by corrosion in the dry air. Groups of men and

children in long blouses like nightshirts idled their

time away on the street corners.

Wives and daughters appeared on the road with

their buckets, going to fetch water from the well on the

other side of the marketplace. They wore bright-colored

pagnes and kerchiefs, covering their traditionally

naked breasts with T-shirts or castoff Western blouses,

since the government in the capital city of Yaoundé

had forbidden women from going topless.

Behind one kiosk in the shade sat a pan holding

several bottles of Coca-Cola, Fanta, and ginger ale,

cooling in water. Some vendors sold a thin stew of

bony fish chunks over gritty rice, others sold fufu, a

doughlike paste of pounded yams to be dipped into a

sauce of meat and okra. Bread merchants stacked their

long baguettes like dry firewood.

Danny used the back of his hand to smear sweatcaked

dust off his forehead, then removed the bandanna

he wore under his helmet to keep the sweat out of

his eyes. With streaks of white skin peeking through

the layer of grit around his eyes, he probably looked

like some strange lemur.

In halting French, he began haggling with a wiry

boy to buy a bottle of water. Hiding behind his kiosk,

the boy demanded 800 francs for the water, an outrageous

price. While Danny attempted to bargain it

down, he saw the gaunt, grayish-skinned man walking

through the marketplace like a wind-up toy running

down.

The man was playing a drum.

The boy cringed and looked away. Danny kept

staring. The crowd seemed to shrink away from the

strange man as he wandered among them, continuing

his incessant beat. He wore his hair long and unruly,

which in itself was unusual among the close-cropped

Africans. In the equatorial heat, the long, stained overcoat

he wore must have heated his body like a furnace,

but the man did not seem to notice. His eyes were

focused on some invisible distance.

“Huit-cent francs,” the boy insisted on his price,

holding the lukewarm bottle of water just out of Danny’s

reach.

The staggering man walked closer, tapping a slow

monotonous beat on the small cylindrical drum under

his arm. He did not change his tempo but continued

to play as if his life depended on it. Danny

saw that the man’s fingers and wrists were wrapped

with scraps of hide; even so, he had beaten his fingertips

bloody.

Danny stood transfixed. He had heard tribal musicians

play all manner of percussion instruments,

from hollowed tree trunks, to rusted metal cans, to

beautifully carved djembe drums with goat-skin drumheads—

but he had never heard a tone so rich and

sweet, with such an odd echoey quality as this strange

African drum.

In the studio, he had messed around with drum

synthesizers and reverbs and the new technology designed

to turn computer hackers into musicians. But

this drum sounded different, solid and pure, and it

hooked him through the heart, hypnotizing him. It

distracted him entirely from the unpleasant appearance

of its bearer.

“What is that?” he asked.

“Sept-cent francs,” the boy insisted in a nervous

whisper, dropping his price to 700 and pushing the

water closer.

Danny walked in front of the staggering man, smiling

broadly enough to show the grit between his teeth, and

listened to the tapping drumbeat. The drummer turned

his gaze to Danny and stared through him. The pupils

of his eyes were like two gaping bullet wounds through

his skull. Danny took a step backward but found himself

moving to the beat. The drummer faced him, finding his

audience. Danny tried to place the rhythm, to burn it

into his mind—something this mesmerizing simply had

to be included in a new Blitzkrieg song.

Danny looked at the cylindrical drum, trying

to determine what might be causing its odd

double-resonance—a thin inner membrane, perhaps?

He saw nothing but elaborate carvings on

the sweat polished wood, and a drumhead with a

smooth, dark-brown coloration. He knew the Africans

used all kinds of skin for their drumheads,

and he couldn’t begin to guess what this was.

He mimed a question to the drummer, then asked,

“Est-ce-que je peux l’essayer?” May I try it?

The gaunt man said nothing, but held out the drum

near enough for Danny to touch it without interrupting

his obsessive rhythm. His overcoat flapped open, and

the hot stench of decay made Danny stagger backward,

but he held his ground, reaching for the drum.

Danny ran his fingers over the smooth drumskin,

then tapped with his fingers. The deep sound resonated

with a beat of its own, like a heartbeat. It delighted

him. “For sale? Est-ce-que c’est a vendre?” He took out

a thousand francs as a starting point, although if water

alone cost 800 francs here, this drum was worth much,

much more.

The man snatched the drum away and clutched

it to his chest, shaking his head vigorously. His drumming

hand continued its unrelenting beat.

Danny took out two thousand francs, then was disappointed

to see not the slightest change of expression

on the odd drummer’s face. “Okay, then, where was the

drum made? Where can I get another one? Où est-ce

qu’on peut trouver un autre comme ça?” He put most of

the money back into his pack, keeping 200 francs out.

Danny stuffed the money into the fist of the drummer;

the man’s hand seemed to be made of petrified

wood. “Où?”

The man scowled, then gestured behind him, toward

the Mandara Mountains along Cameroon’s border

with Nigeria. “Kabas.”

He turned and staggered away, still tapping on

his drum as if to mark his footsteps. Danny watched

him go, then returned to the kiosk, unfolding the map

from his pack. “Where is this Kabas? Is it a place? C’est

un village?”

“Huit-cent francs,” the boy said, offering the water

again at his original 800 franc price.

Danny bought the water, and the boy gave

him directions.

He spent the night in a Garouan hotel that made Motel

6 look like Caesar’s Palace. Anxious to be on his way

to find his own new drum, Danny roused a local vendor

and cajoled him into preparing a quick omelet for

breakfast. He took a sip from his 800 franc bottle of water,

saving the rest for the long bike ride, then pedaled

off into the stirring sounds of early morning.

As Danny left Garoua on the main road, heading

toward the mountains, savanna and thorn trees

stretched away under a crystal sky. A pair of doves

bathed in the dust of the road ahead, but as he rode toward

them, they flew up into the last of the trees with

a chuk-chuk of alarm and a flash of white tail feathers.

Smoke from grassfires on the plains tainted the air.

How different it was to be riding through a landscape,

he thought—with no walls or windows between

his senses and the world—rather than just riding by it.

Danny felt the road under his thin wheels, the sun, the

wind on his body. It made a strange place less exotic,

yet it became infinitely more real.

The road out of Garoua was a wide boulevard that

turned into a smaller road heading north. With his

bicycle tires humming and crunching on the irregular

pavement, Danny passed a few ragged cotton fields,

then entered the plains of dry, yellow grass and thorny

scrub, everywhere studded with boulders and sculpted

anthills. By 7:30 in the morning, a hot breeze rose,

carrying a honeysuckle-like perfume. Everything vibrated

with heat.

Within an hour, the road grew worse, but Danny

kept his pace, taking deep breaths in the trancelike

state that kept the horizon moving closer. Drums.

Kabas. Long rides helped him clear his head, but he

found he had to concentrate to steer around the worst

ruts and the biggest stones.

Great columns of stone appeared above the hills

to east and west. One was pyramid-shaped, one a

huge rounded breast, yet another a great stone phallus.

Danny had seen photographs of these “inselberg” formations

caused by volcanoes that had eroded over the

eons, leaving behind vertical cores of lava.

Erosion had struck the road here too, turning it

into a heaving washboard, which then veered left into

a trough between tumbled boulders and up through

a gauntlet of thorn trees. Danny stopped for another

drink of water, another glance at the map. The water

boy at the kiosk had marked the location of Kabas

with his fingernail, but it was not printed on the map.

After Danny had climbed uphill for an hour, the

beaten path became no more than a worn trail, forcing

him to squeeze between walls of thorns and dry millet

stalks. The squadrons of hovering dragonflies were

harmless, but the hordes of tiny flies circling his face

were maddening, and he couldn’t pedal fast enough to

escape them.

It was nearly noon, the sun reflecting straight up

from the dry earth, and the little shade cast by the scattered

trees dwindled to a small circle around the trunks.

“Where the hell am I going?” he said to the sky.

But in his head, he kept hearing the odd, potent

beat resonating from the bizarre drum he had seen

in the Garoua marketplace. He recalled the grayish,

shambling man who had never once stopped tapping

on his drum, even though his fingers bled. No matter

how bad the road got, Danny thought, he would keep

going. He’d never been so intrigued by a drumbeat before,

and he never left things half-finished.

Danny Imbro was a goal-oriented person. The

other members of Blitzkrieg razzed him about it,

that once he made up his mind to do something, he

plowed ahead, defying all common sense. Back in

school, he had made up his mind to be a drummer.

He had hammered away at just about every object in

sight with his fingertips, pencils, silverware, anything

that made noise. He kept at it until he drove everyone

else around him nuts, and somewhere along the line

he became good.

Now people stood at the chain link fences behind

concert halls and applauded whenever he walked from

the backstage dressing rooms out to the tour buses—as

if he were somehow doing a better job of walking than

any of them had ever seen before…

Up ahead, an enormous buttress tree, a gnarled

and twisted pair of trunks hung with cable-thick vines,

cast a wide patch of shade. Beneath the tree, watching

him approach, sat a small boy.

The boy leaped to his feet, as if he had been

waiting for Danny. Shirtless and dusty, he held a

hooklike, withered arm against his chest; but his

grin was completely disarming. “Je suis guide?” the

boy called.

Relief stifled Danny’s laugh. He nodded vigorously.

“Oui!” Yes, he could certainly use a guide right

about now. “Je cherche Kabas—village des tambours.

The village of drums.”

The smiling boy danced around like a goat, jumping

from rock to rock. He was pleasant-faced and

healthy looking, except for the crippled arm; his skin

was very dark, but his eyes had a slight Asian cast. He

chattered in a high voice, a mixture of French and native

dialect. Danny caught enough to understand that

the boy’s name was Anatole.

end excerpt...

AFTERWORD: STORIES THAT FIRED MY IMAGINATION

NEIL PEART

In the late ’80s, a novel called Resurr ection,

Inc. arrived in my mailbox, accompanied by a letter

from the author, Kevin J. Anderson. He wrote that

the book had been partly inspired by an album called

Grace Under Pressure, which my Rush bandmates and

I had released in 1984.

It took me a year or so to get around to reading

Resurrection, Inc., but when I did, I was powerfully impressed,

and wrote back to Kevin to tell him so. Any

inspiration from Rush’s work seemed indirect, at best,

but nonetheless, Kevin and I had much in common,

not least a shared love since childhood for science fiction

and fantasy stories.

We began to write to each other occasionally, and

during Rush’s Roll the Bones tour in 1991, on a day off

between concerts in California, I rode my bicycle from

Sacramento to Kevin’s home in Dublin, California.

That was the beginning of a good friendship, many

stimulating conversations (mostly by letter and e-mail,

as we lived far apart), and regular packages in the mail,

as we shared our latest work with each other—the ultimate

stimulating conversation. In subsequent years I

would send Kevin a few books of my own, numerous

CDs and DVDs from my work with Rush, and there

seemed to be a fat volume from Kevin arriving about

every other month.

Back in 1991, though, Kevin was still working

full-time as a technical writer at the Lawrence Livermore

National Laboratory. He spent every spare

minute working on his fiction, and though he would

famously collect over 750 rejection letters, there was

no doubt in Kevin’s mind about his destiny. Even as a

child, Kevin didn’t “want to be” a writer when he grew

up; he was going to be a writer.

And so he was. To date, Kevin has published

over 80 novels, story collections, graphic novels,

and comic books, and he still spends every minute

being a writer. Kevin doesn’t write to live, he lives

to write.

He has even found ways to weave his recreation,

relaxation, and desire for adventure and physical challenge

into the writing process, carrying a microcassette

recorder on long hikes throughout the West, including

the ascent of each of Colorado’s 46 “fourteeners,”

(peaks over 14,000 feet).

In a recent exchange of e-mails, Kevin and I were

discussing writing styles and habits, and he offered this

revealing passage:

A long time ago, my friend and collaborator Doug Beason made a joking comment when I suggested that I needed a break, a sabbatical. He said, “Kevin, if you ever stop writing, your head would explode!”

And I knew he was right. My imagination is stuck in overdrive, for better or worse. Instead of a writer calling for a Muse to give him an idea, I’ve got a hyperactive Muse that won’t leave me alone.

I feel as if my head is a pot filled with too many popcorn kernels, popping away, filling the container and pushing the lid up, and unless I keep shoveling the new stuff out, the whole thing will blow up on me. I’m writing as fast as I can to keep the growling, slavering Ideas from nipping too close at my heels.

There was a US News & World Report article a few months ago about a newly “found” disease they called “hypergraphia,” the compulsion to write. They said writers like Sylvia Plath and Tolstoy were so obsessed with writing they often wrote as much as a thousand words a day. (A thousand words? Man, I’ve done over 10,000 words in a day!) I guess I’m an addict.

I’m picturing you as a guy with a similar compulsion to drum, slapping your knees, the furniture, the walls, feeling a rhythm in your blood. It’s what you do. For me, stories are the drumbeats inside me. I’m always fabricating stories, characters, weird locations, plot twists. I’m just not happy “relaxing.” Sometimes I’m just banging around having fun, goofing with toys that I enjoy—as when I write Star Wars or comics or light books like Sky Captain; other times I’m intense and working on something I think is Really Important, like Hopscotch. The “Seven Suns” books are a little of both, the biggest and most challenging story I’ve ever told, but damn, I’m having the time of my life with it too.

I’ve been saying for years and years, “soon I’ll slow down and take more time to smell the roses.” It’ll never happen, I suppose, because I just love the writing so much. Three days ago, I started writing Seven Suns #5, and I was in absolute euphoria plotting the 112 chapters. This happens, then this happens, then this happens—I was discovering what my beloved characters were going to do, where they would end up, who would die, who would triumph. I came up with some twists and new ideas that were revelations to me, real lightning bolts from the hyperactive Muse—and best of all, they were so logical and inevitable in the universe of the story, that it seemed as if they were sewn into the fabric of my imagination from the very beginning, but I just didn’t realize it yet. Now that’s cool.

So, yes, I would like to have that sense of stillness and the time to pay attention deeply to the things around me … but on the other hand, I can’t wait to see what happens next in the new novel that’s just over the horizon.

And Kevin Anderson’s horizons are wider than

most—infinite, really. His imagination roams the entire

universe, creating strange new worlds and peopling

them with strong, believable characters.

From the philosophical depth of Resurrection,

Inc. and Hopscotch, to the novelizations for Star Wars

and The X-Files; from the genre of “historical fantasy”

(which I think Kevin invented—richly-imagined

tales about Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Charles

Dickens), to the breathtaking scope of his “imagineering”

in the Seven Suns series, there have been so

many excellent works that have delighted this reader,

and millions of others.

Among seemingly overlooked treasures, I fondly

remember the fantasy trilogy, Gamearth, Gameplay,

and Game’s End, but there are also Kevin’s collaborations

with Doug Beason, like The Trinity Paradox and

Ill Wind, and the ongoing, highly successful Dune series

with Brian Herbert.

In writing to Kevin in response to reading one of

those, The Butlerian Jihad, I talked about the subtle

skill of his craft:

More and more I notice how truly masterful writing, yours and others’, leaves the reader with an overall impression of making it all seem easy—regardless of how much work has gone into the craft, the background, the research, and the intellectual underpinnings (or maybe because of all that), it just breathes off the page in a smooth flow of seemingly-inevitable revelations.

I know I’ve made similar comments about drummers before: some of them try to make simple things look difficult and impressive, but the true masters make the impossible seem easy.

It doesn’t seem fair to the creator of that carefully wrought illusion, undermining all the effort and experience necessary to operate at that rarefied level, but it’s the ultimate nature of mastery, I guess. (It may be lonely at the top, but it must feel better than being at the bottom!)

In late 2002, toward the end of a long American tour that had me drained and feeling sorry for myself, I wrote to Kevin:

One bright spot I can report along the way is that during some idle hours in the tuning room, on the bus, and in hotel rooms, I had the great pleasure of reading Hidden Empire.

First of all, I have to tell you that if you or anyone else had any doubt, I think you have achieved a true Masterpiece with this book—meaning that term in the sense which you clarified for me years ago. It is definitely a piece of work to lay alongside those of the Masters, to be accepted by them and by the great abstraction of “the Audience” as one of the pantheon of masters yourself.

Congratulations. I really think it is a great book. I was so impressed by it at the time, and also after the fact—a true test of quality, I’m sure you’ll agree.

The craftsmanship alone is sheer perfection. The architecture of the storytelling moves forward with grace and economy, combining girders and panels of deft characterizations, wondrous settings, admirable “imagineering,” and all the superstructure of pure thought that has preceded all that.

(The reader will have observed by now that when

Kevin asked me to write this essay, it was easy to say

yes—I knew the important stuff had already been

written, either by me or by him. I would only have to

look it up!)

Here are some of Kevin’s thoughts on “style,” from

a recent exchange of e-mails on the subject:

I think in a letter to you many years ago, I talked about creating believable worlds and scenes; one of the vital tricks I mentioned was to nail down a few small but very precise and mundane details (the color of a piece of lint, the brand of a gum wrapper wadded up in a gutter), and the reader will buy into the rest of what you’re describing. It seems easy, seems transparent. It’s simple to show off, to be flashy and flamboyant, to prance around and point at marvelous overblown metaphors. It’s more difficult to be subtle.

To which I replied, in part:

Another note about writing style that occurred to me in connection with what I wrote the other day: I just finished Gabriel García Márquez’s memoir, Living to Tell the Tale, and he described his early decision as a writer to avoid all adverbs of the “ly” sort (mento in Spanish, I think), and how it became almost pathological with him, just as Hemingway tried to cut every unnecessary adjective.

In your case, with the necessary “mission” of describing an entirely imaginary universe for the reader, it would seem especially difficult to avoid extraneous adjectives and adverbs—and yet you do, making the descriptions of planets, cities, palaces, customs, and technology fall more-or-less naturally into the ongoing narrative. And … you make it look so easy.

As we have discussed, that is the highest level of craft, and yet the least likely to be admired, or even appreciated. Once I offered a definition of genius, in particular reference to Buddy Rich: “Doing the impossible, and making it look easy.”

And yes, Kevin does make it look easy, though

of course it’s not. He works to a very high standard

of quality in his writing, from the conception to the

execution, and these stories are a testament to the consistency

of his art.

When people have called him lucky, Kevin likes to

counter, “Yes, and the harder I work, the luckier I get.”

As one of his appreciative readers, I think the

harder Kevin works, the luckier we get.

—Neil Peart

“The measure of a life is a measure of love and respect.”

—Neil Peart, “The Garden”

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Kevin J. Anderson is the bestselling science-fiction

author of 165 novels. His original works include the

Saga of Seven Suns series; Spine of the Dragon; the Terra

Incognita trilogy; and with Brian Herbert, is the

co-author of 15 novels in the Dune universe. He has

written spin-off novels for Star Wars, DC Comics, and

The X-Files. His first novel, Resurrection, Inc., was inspired

by the Rush album Grace Under Pressure, with

lyrics by Neil Peart.

Neil Peart is the drummer and lyricist of the legendary

rock band Rush and the author of Ghost Rider,

The Masked Rider, Traveling Music, Roadshow, Far and

Away, Far and Near, and Far and Wide.

Anderson and Peart coauthored the steampunk

fantasy novels Clockwork Angels and Clockwork Lives,

as well as graphic novel adaptations of both, and the

story “Drumbeats.”

Neil Peart passed away January 2020 after a long

battle with brain cancer.

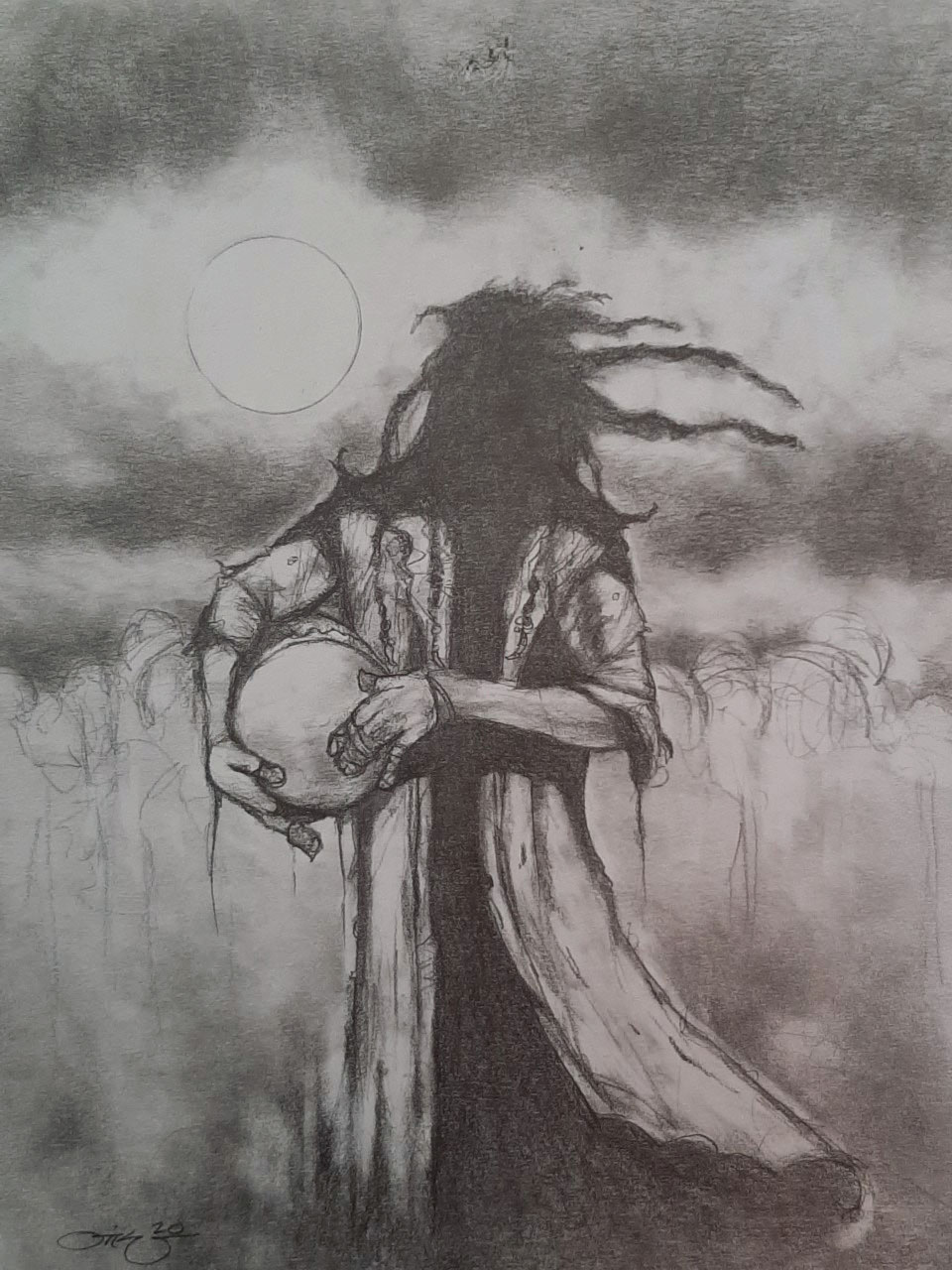

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Steve Otis is an accomplished comic artist, illustrator,

sculptor, and teacher. He started to draw at a very

early age, fueled by images of DC and Marvel comics,

and then the great Warren magazines (Creepy and

Eerie in the early 70s). From there he began to delve

more deeply into horror, gothic and sci fi art. Heavily

influenced by Frazetta, Boris and Richard Corben,

he did extensive fantasy work in the late nineties for

collectible card games. By the early 2000s, he began

to look for techniques to challenge his artistic style

in a more “Fine Art” vein while keeping firmly to the

themes of dark art.

Steve graduated from the Laval University of

Quebec with a major in Art Teaching. He taught art

in high school for ten years before concentrating on

painting. He has participated in many solo exhibitions

and collective art shows in Quebec, Montreal, Italy

and a few states in the USA.

He discovered Rush in 1979 with Hemispheres. The

words of Neil Peart resounded on my heartstrings, from

his trippy sci fi lyrics of the late seventies to the worldview

lyrics of his recent works. Neil’s astonishing drumming

made Steve an amazingly inept air drummer at

over 17 Rush concerts from 1981–2015. It is his great

honor and privilege to take part in this project.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This story was written a long time ago, and we

never imagined it would still be around decades later.

I’m so glad to see it have a new life.

These are just my own, Kevin’s, acknowledgments,

and even though he is my coauthor, I cannot express

enough gratitude to Neil Peart, not only for this story

but for all the memories we shared, all the inspiration

he gave me, and the ideas I will never forget.

And to my wife Rebecca Moesta, whom Neil called

“a great partner for an obsessive writer” (and he’s right!),

who has helped to improve not only this story but all

my writing. And Neil’s wife Carrie and daughter Olivia.

Steve Otis, brilliant artist, stepped up to the plate

without even being asked to create this gorgeous volume.

Allyson Longueira created the interior layout to

let the story shine. Janet McDonald did the wonderful

cover design.

And finally, a special thanks to the whole Rush

family who showed such tremendous support, love,

and gratitude in a difficult time, Love and respect to

all of you.

DRUMBEATS: Special Edition