|

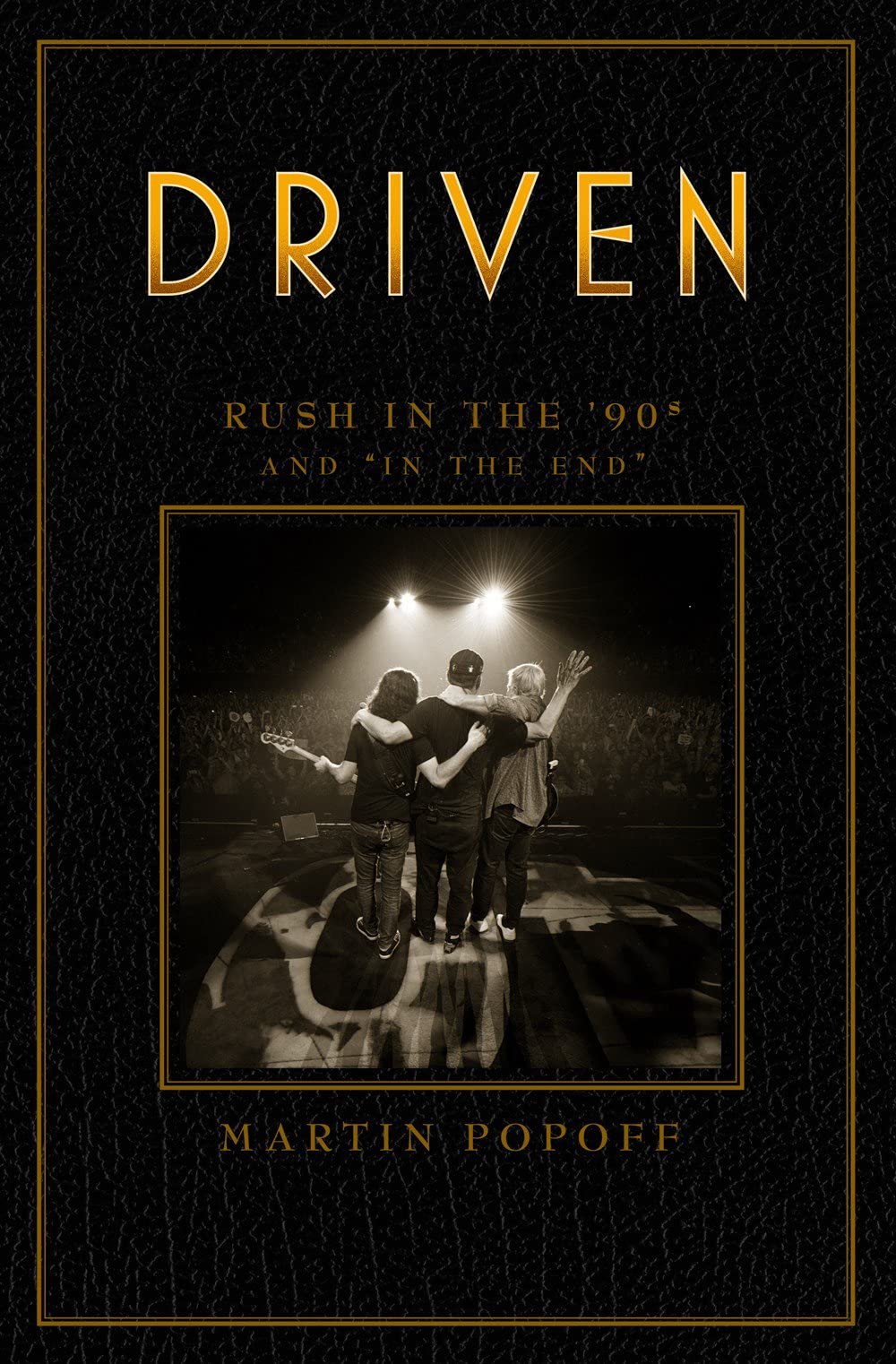

Rush in the '90s and 'In the End' Rush Across the Decades, Book 3 by Martin Popoff April 27th, 2021 |

In the conclusion to the trilogy of authoritative books on what is unarguably Canada's most beloved and successful rock institution ever, Martin Popoff takes us through the arc of

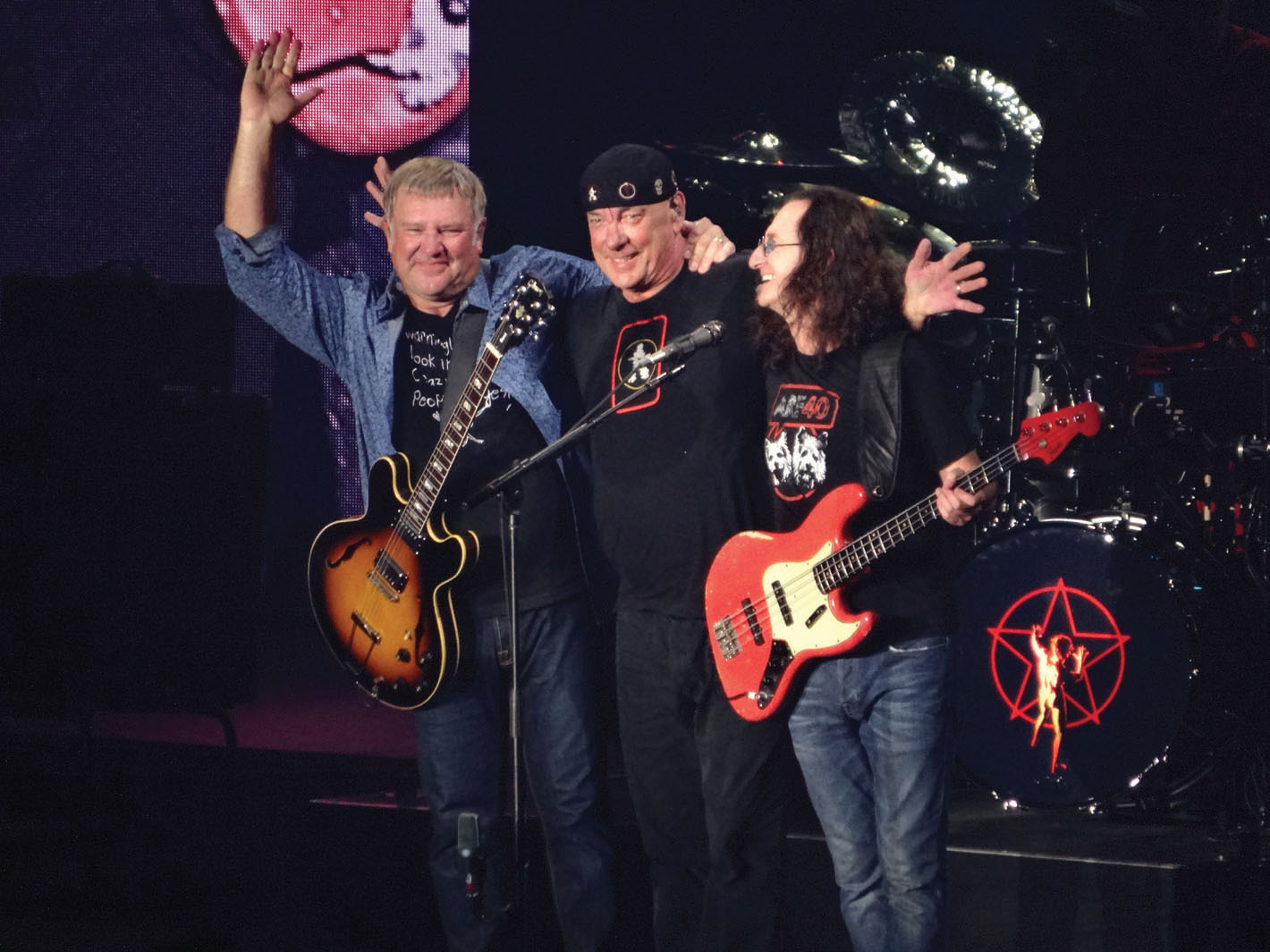

three decades in the lives of Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart. Driven is ultimately about life at the top, from a decade that begins with the brisk-selling Roll the Bones album to the throngs of fans who took in Rush shows during their last twenty-five years.

But there is also unimaginable tragedy along the way, with one of the world's greatest drummers, Neil Peart, losing his daughter and his common law wife within the space of ten months, and then himself suc-cumbing to cancer four years after the band's retirement — his shocking, unexpected passing resulted in amendments to this work long after it had already been completed. In between, however, there is a gorgeous and heartbreaking album of reflection and bereavement, as well as a conquering trip to Brazil, a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction and — some say surprisingly — the band's first full-blown concept album to close an immense career marked by integrity and idealism.

• "Die-hard Rush fans will devour this fascinating deep-dive into the band's musically controversial decade." — PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

• "Popoff continues to demonstrate a vast understanding of the band." — SPILL MAGAZINE

• "Knowing the band's music inside and out, he gets to what a real fan wants to know." — VINTAGE ROCK

• "A treasure trove of enlightening and entertaining glimpses into the workings of three complex individuals." — LIBRARY JOURNAL

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter 1: Roll the Bones

Chapter 2: Counterparts

Chapter 3: Test for Echo

Chapter 4: Different Stages

Chapter 5: Vapor Trails

Chapter 6: Rush in Rio

Chapter 7: Snakes & Arrows

Chapter 8: Clockwork Angels

Chapter 9: “In the End”

Discography

Credits

About the Author

Martin Popoff — A Complete Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

The book you now hold in your hands marks the conclusion

of a trilogy, a long journey down the path of progressive

metal greatness. It started with Anthem: Rush in the ’70s and

was perpetuated and provoked by Limelight: Rush in the ’80s, and

it concludes now, beyond bittersweet, after the death of Neil

Peart from brain cancer on January 7, 2020.

The dark news came to light near the end of the production

process for Anthem and Limelight, so in those books Neil remains

forever alive and disseminating his wisdoms as “the Professor.”

But the tragic end to one of rock’s towering greats can’t be

avoided any longer, and so it is part of this story.

For now, however, some background for you, on the subject

of this book. If you are wondering why — or indeed how — this

book exists, let me explain, quoting more or less verbatim from

the intro of the first book from way, way back, Anthem, if I may.

There I wrote:

As you may be aware, this is my fourth Rush book, following Contents Under Pressure: 30 Years of Rush at Home & Away, Rush: The Illustrated History and Rush: Album by Album. And since those, there have been a number of interesting developments that made me want to write this one.Now, to the present tome, what to make of Rush in the ’90s and “in the end,” so to speak, the 2000s and the 2010s, right up until the band’s retirement in 2015 and the great loss to family and friends resulting from Neil’s being taken from us in 2020? Obviously, we’ll get to that, but this is the place for a spot of personal reflection, so here goes. As an angry metalhead more excited by what Pantera was doing to music now that they had Phil and a major label deal, the twee tones of Roll the Bones had me casting that record aside pretty quick. Sure, there’s always excitement around a Rush album, and this one for some reason generated a bit more than usual, but still, I wasn’t happy. When Counterparts launched, to my mind, Rush was back — the music was full-bodied, the writing not appreciably different, but it wasn’t hobbled by a lightness that brought the already underpopulated trio down to what seemed like 2.5 or 2.25 members. I loved the record, loved the resonance of the bass, the boom of the drums, the authority howling out of the guitars. Test for Echo left me cold, like the album cover, and then right after, we all had to deal with the shock of the horror that was Neil’s personal life after the death of his daughter, Selena, and then his common-law wife, Jackie. Maybe it was the end of Rush: Alex and Geddy both had solo albums (that sounded like Rush in the ’90s), and there were a hundred other flavors. Yes, maybe this was the end.

To start, only one of those three books, Contents, was a traditional biography — an authorized one at that — but it was quite short, and given that it came out in 2004 before Rush was officially retired, it was in need of an update. I thought about it, but I wasn’t feeling it, not without some vigorous additions.

That, fortunately, took care of itself. In the early 2010s, I found myself working with Sam Dunn and Scot McFadyen at Banger Films on the award-winning documentary Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage. Anybody who works in docs will tell you that between the different speakers and non-talk footage that has to get into what might end up a ninety- minute film, only a tiny percentage of the interview footage ever gets used, the rest just sits in archive, rarely seen or heard by anyone. Long and short of it, I arranged to use that archive, along with more interviews I’d done over the years, plus the odd quote from the available press, to get this book to the point where I felt it was bringing something new and significant to the table of Rush books.

So there you have it, thanks in large part to those guys — as well as the kind consent of Pegi Cecconi at the Rush office — the book you hold in your hands more than ably supplants Contents Under Pressure and stands as the most strident and detailed analysis of the Rush catalogue in existence.

Fortunately, it was not to be. Neil mended as best as could be expected under the circumstances, and the band returned with a masterful new record, Vapor Trails. I don’t know what it is about this record, but putting aside the dark wisdom of its lyrics, it’s arguably the best of a top-shelf canon thus far. I felt like this was the first time since Grace Under Pressure that the band had created a whole new style of music, and it was art at the same time. I loved the record — still do — old mix, remix. I’ve always got time for Vapor Trails.

So then a weird thing happens. I do the Contents Under Pressure book and then work at Banger on the movie. Add another couple of Rush books later on, get interviewed for a couple of Rush docs, and suddenly, Rush reminds me of work. I imagine that’s where I am any time I even think to put a Rush record on (this reticence fades, fortunately). But yes, here I am living in Toronto, and it’s all Rush all the time and I’m full up. But then — God love the guys — Snakes & Arrows is issued, and it’s all fresh again. Something has shifted since Vapor Trails. Whether it’s new producer Nick Raskulinecz or just the band’s typical rapid growth, suddenly there’s a new sound, if I can generalize, one characterized by warmth along with acoustic guitars massaged in with electrics.

Next came Clockwork Angels and little did we know it would be the last. Not only was this a record that lived lively like its predecessor, but there was an additional heaviness due to the subtraction of the acoustics. What’s more, Rush delivered their first concept album proper after stopping at a full side in the past. Here they barreled on through a somewhat befuddling plot, but one brimming with rich imagery with the addition of steampunk to the stew, which was stressed more through the stage sets of the tour.

Then it was all over with a languid goodbye, the band touring the record proper and then embarking on something called R40, a fortieth anniversary tour that found the band playing songs from their catalogue in reverse chronological order, making progressively modest their stage set in tandem, until there they were, three kids rocking songs from 1974.

Four years and five months after the band’s last show, the shocking news reverberated through the rock community that Neil had died, and it was horribly clear to all that the soft retirement of Rush was final. More, unfortunately, on this later, but there you go. That’s where Rush ends and that’s where we can end this set of three books, this particular tome celebrating the biggest expanse of years and the worst news imaginable, but on the happy side, there is a raft of records similar to those covered in both Anthem and Limelight. In any event, thanks for reading along. Whether you parachuted in here with modern Rush or have been following the bouncing ball since the first book, I’m glad to share my deep appreciation of Rush with you. Without further ado, in the immortal words of the Professor, “Why are we here? Because we’re here. Roll the bones.”

-Martin Popoff

CHAPTER 1: ROLL THE BONES

“We keep looking for the better version of Rush.”

Here’s how the ’90s started for Rush.

One week after Geddy, Alex and Neil would propose

an austere something-or-other called Roll the Bones, Guns

N’ Roses would drop two near-double albums, Use Your Illusion

I and Use Your Illusion II.

Another week goes by and on September 24, 1991, Nirvana

offered for your consideration their second album, Nevermind,

led by a little something called “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

Roll the Bones did not sound like Guns N’ Roses or Nirvana,

nor did it sound like really anything out there (and that’s not

necessarily a good thing), other than Presto, Rush’s similarly thin,

mild and modest record from two years previous when the band

was facing the same realities: hair metal, grunge and thrash at

the fore, Rush’s brand of progressive bonsai tree and origami pop

— a curious thing — but let’s go see Rush anyway.

But credit to the guys in one sense: they were believing in the

stark and odd and oddball evolutionary path they were on and

damn the torpedoes. Rupert Hine returned as producer, signifying

that they thought they got it right on Presto. Rupert was

in a sort of fourth member role in the Rush cabal, which helps

underscore the identity of any given project.

“We felt we were missing something,” figures Geddy, on the

importance of these strong outside voices. “We felt we weren’t

learning enough. It’s like going into a fantastic restaurant and

seeing all these great dishes and wanting to try all of them; that’s

how we were. We felt like we had this great start. We had this

great upbringing, and we learned a hell of a lot about making

records. We were born into this rock world, and we had some

tools and we wanted to refine those tools. And the only way to

do that was to work with more people, different people.

“Because of the style of music we played, there was a real bias

against kind of progressive heavy metal, and we found it difficult

to work with all the producers we wanted to work with. And

so every time out, we had a new list of people. We came into

this whole mode of unearthing producers that maybe would be

unlikely people for us to work with, but we felt had some real

heart as producers. And that started the whole thing. It’s like,

when it’s time to make a record, let’s dig up the names, let’s pick

up the lists. Who can we find? Who is out there? Who is just

coming into his own as a producer? And can we grab some of

that excitement?

“In the early days of doing that, it was experience we were

after. I think now, and especially with Nick, it’s youthful energy

and a different attitude toward making records, and that’s a way

for us to stay current. We can’t help being who we are, and we’re

not going to work with anybody else. There’s the three of us, and

we’re dedicated to that, so what’s the easiest thing to change?

It’s the people around you when you make a record. That’s the

easiest way — and for me the smartest way — of bringing new

energy, new ideas, into an old idea — Rush — you know? A

forty-year-old idea.”

Reflects Rupert: “At the time, because of the urge to keep

things fresh, you are looking for all kinds of ways of moving

the parts around, and some input, some random input. That just

marks them as wanting to stay in the world of making records

together, because they could have split up, they could have

formed three independent bands based on each other and done a

million things with the kind of fan base they had, and still had a

pretty good living. But they were never tempted to do that, and

the odd solo record is always very much a sidebar project.

“There’s the absolute will to stay together and find out just

how far these three people in each other’s pockets can travel. And

I don’t think it’s ever a scramble, I don’t think it’s ever desperate,

I think it’s always willful, it’s always thought about in advance,

it’s always to a degree calculated, in terms of the moment they

ask this random input to come into their world. It’s a calculated

decision about a point that’s been well thought out by them.

They’re in masterful control of their lives and the band’s direction.

That in itself is so unique — it’s one of the many truly

unique things about this band.”

Typical of the civilized men of letters that they were, Rush

went on a writing retreat in advance of making the new record,

holing up at Chalet Studio in Claremont, Ontario, for two and

a half months to write, each in their longstanding roles. When

not birdwatching and repairing birdfeeders, Geddy and Alex

would put music to Alex’s rudimentary drum machine patterns,

the two convening with Neil in the evening to see what they

could cook up together. As with Presto, writing centered around

guitar, bass and drums and not keyboards, with a heavy emphasis

on vocal melodies as well — common parlance would eventually

position the Rupert Hine years as the singing era, where

Geddy would shift the attention he was placing on keyboards

over to the making of memorable vocal melodies, or melodies

that played a stronger role in the song, almost as a fourth instrumental

narrative.

“It felt to me very much like a part two,” agrees Rupert. “But

the second part built on how they felt about part one, meaning

Geddy liked that his voice was in these different registers.

He understood why I thought it had made a difference, and he

liked it. And I think they were encouraged by the three-piece

idea again and minimalizing the keyboards. We carried on doing

that, and so there’s probably even less keyboards on that record,

and there weren’t many on Presto, certainly not compared with

the previous two albums.

“But I find it hard not to think of them as one piece. I’m not

sure I went into the second album with anything like the objectives

we had for the first because it had seemed like the objectives

had made sufficient change — and the band had themselves

compounded on that change. I would say things were amplified.

There was no real ‘Well, the one thing we got wrong with

Presto was blah, blah, blah, so this time we’ll try this.’ I think

everything was compounded, which was encouraging from my

perspective. It seemed to be starting off with an enthusiastic kick

up the bum.”

In other words, the guys were happy with what they had done

on Presto. Even if there were less keyboards, no one at this time

was concerned with heavy, rocking Rush. Alex was exploring

texture, color, atmosphere, funk and acoustic guitar, and all five

of those descriptives tend to put the guitar in a supportive role.

In support of what? Well, vocals, and thus almost automatically,

lyrics. Bass would and could be moderately busy in that wee and

twee box, drums slightly less so, pretty much on par with guitar.

All of this adds up to a hermetically sealed bubble of Rush’s own

making, a contrivance even, albeit one that moves along an evolutionary

path. Forget what’s happening with surging wider tidal

musical gyres; there’s this thing we are doing, and we’d like you

to hear it.

“I don’t recall ever having a discussion with individual Rush

members about any other band or music,” muses Rupert. “Of

course I was only too happy to keep any sonic interference out of

the way and just look at the purity of what the band can do. That’s

not strictly true, because you’ve just rung a bell: I do remember

talking to Neil about Living Colour, but I imagine with respect

to some relatively ideological stance, nothing directly affecting

the band. I mean, I delighted in the fact that not once did Alex

ever say to me, ‘You know for this track, I sort of thought the

sound of the guitar could be a bit like . . .’ Never went there.

“And almost every band, it’s like, ‘You know that sound of

that part on so-and-so’s track? When they do that?’ And you

work from there. I always love the idea that you have an absolutely

blank page for everything, for every song, for every album,

for every part. You just start with, ‘Well, I wonder what we could

do to make this part really sing, really work, you know?’ And

not to jump outside of any frame of reference, other than your

own, so you can dig into some mad little demo that you did on a

matchbox ten years ago and say, ‘Here, look, I love this’ and, ‘Oh,

yeah, let’s take that.’ That will just be more intensely them. Just

borrow from your own oeuvre.

“I can’t say that Roll the Bones is part of the era when the

Seattle sound was out. It feels to me like we were in absolute

isolation of it, but I wouldn’t really encourage them in any other

way than to be aware. You can’t not be aware if you’re musical.

I’m not suggesting people go and live on an island and listen

to nothing — you’ve got to soak in the musicality of the planet

without a doubt — but you’re going to do that anyway, if your

eyes are open and you’re musical.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever known where Rush is in the musical

landscape, to be quite honest,” chuckles Geddy. “I don’t think

any of us do. And that’s a blessing because we go in and do what

we think is fun to do and what is cool to do. Yeah, we listen to

other things and we try to bring new things in. At that time, it

was kind of the beginning of rap and hip-hop and all this, and

Neil wrote this really funny kind of piss-take on this whole thing,

and we thought, why don’t we throw that in the song? And that’s

how that whole middle section of ‘Roll the Bones’ came to be.

It was just us having fun playing this goofy background kind of

rhythmic track and then rapping on it.

“So we basically have no plan. I think a lot of bands do have

a grand plan, master plan, and we don’t really have that. At the

start of a record, we just don’t know what’s going to happen. We

just let it happen. Certainly, I wanted to improve the songwriting

on the Roll the Bones album, because I had that feeling we were

more style than content on Presto. That was kind of the residue

that was left with me from Presto. ‘The Pass’ was really strong,

but a lot of the other songs on that album didn’t really stay with

me from a song resonance point of view. And so we really focused

on the songwriting, and I think we nailed that. I think a lot of the

songs on Roll the Bones are really strong.

“But we’re always experimenting,” continues Geddy. “I mean,

just because we got successful doesn’t mean we’re going to

stop. That’s the way I look at it. We could’ve gone in and done

Moving Pictures all over again, but we’re not really well built for

that. We’re too curious; we’re too dissatisfied with where we’re

at, so we feel we have to keep moving. We have to find the better

Rush, you know. We keep looking for the better version of Rush.

“And even though we’ve got this great success — oh, that’s

great, we’ve got success, we can do headline shows, we can spend

more money on productions — it afforded us a hell of a lot of

latitude, but it didn’t change that feeling when we get together to

work on our music: ‘Okay, what will make us better? What will

make us better writers, better producers, better players?’ That’s

the motivation. Maybe it seems like we just started experimenting

after that time, but if you look at the first Rush album and

then listen to Fly by Night, they’re completely different records.

What does ‘By-Tor & the Snow Dog’ have to do with ‘Finding

My Way’? Worlds apart. That’s when the experimenting started.

And then look at Caress of Steel. That’s an experiment in hash oil!

We’ve always experimented.

“We’ve also always been pigeonholed and categorized. Most

bands are, I guess. But I felt there was always more to us than the

labels that were attached to us. I felt there was more going on,

and we were easily written off as a three-piece metal band, or a

prog band, or a sword-and-sorcery band. Maybe that’s a motivator

for us, in a way. Keep trying to shuffle those labels off of us,

you know? At the end of the day though, we’re a hard rock band

— I’ve said that many times. I identify with that, and I think we

would all agree about that — if we had to be labeled anything, it

would be a hard rock band.”

The guys were so prepared coming out of the writing sessions

for Roll the Bones that the performances and arrangements on

the demos were referenced quite closely, with Neil nailing his

meticulously mapped drum parts with ruthless efficiency. The

album was recorded between February and May of ’91, using

the idyllic and storied Le Studio in Morin Heights as well as

McClear Place back home in Toronto. Thanks in the album’s

liner notes would go to the birds, reflecting Geddy’s new hobby,

and CNN, which the guys watched a lot, staying abreast of the

news. Things went so smoothly — drums and bass put down in

four days, guitars in eight — the guys finished two months early,

moving the release date three months forward from the initially

proposed January of 1992.

“We sort of do that,” mused Alex, on using Rupert Hine for

a second time. “We like to give a producer a couple of chances.

The experience was positive, everything seemed to go well, the

album did well, and I don’t think we had any fears of working

with him again. We thought that would be a good thing, so we

just continued. Rupert has a great sense of musicality, arrangement,

songwriting. That’s really what he brought to the whole

project. We’re pretty set in our ways. We know what we want to

achieve. It’s nice that we have somebody there to guide it along

and make some of the decisions that we don’t wanna make. And

I think that record got a little more meat on it. It was a little

heavier, or harder. Good songs and some good arrangements.

“But it’s a funny thing with us, working with producers at least

a couple of times. Maybe once you haven’t realized the depth of

the relationship and how far you can go. I mean, we always learn

from everybody we work with — that’s always key. I wonder

now if we should just do it once and move on and go with the

unknown. That’s exciting and challenging. With Terry, during

those first few years, we were recording two albums a year, so it

was a different environment. We hadn’t reached the stage where

we incorporated other instruments; the band was simpler in its

form and very comfortable with Terry. But after nine records, it

was really time for us to move on and work with other people.

“You don’t want to stay in the same place, ever,” continues

Lifeson. “It’s boring and you get itchy and antsy and you want

to move on. And that’s always been the thing with us. It’s easy to

do something over and over and over and over, like some current

bands that are very popular, that have a particular sound and a

very identifiable singer’s voice. They just create the same album

over and over. It’s a great success, and that’s fine, but eventually

that ends and it’s over and there is no growth, there’s no development.

You can look back and say, well, I made a lot of money,

and that’s all fine and good, but really what does it do for you?

It’s always been key for us to change and to move forward. We

experimented a lot. We’ve taken some chances and we tried some

things, and we haven’t always been successful. And our fans have

been vocal about those things, what they like and what they don’t

like. And I’m kind of proud of the stuff I don’t like, because we

learned from it, and we’re always moving forward. We’re always

thinking about how to approach something in a different way.

“Well, not albums,” laughs Alex, not willing to say whole

records failed. “Some songs are certainly weaker. And of course,

you feel this once you get more distance from the album. They

can’t be helped. We never started with twenty songs and burned

it down to the best twelve. We always work on those twelve,

and that’s all you get. So it’s do them all one hundred percent.

Invariably there are some weaker songs than others. There’s a lot

of information, a lot of music to work on. That’s why we have

producers, someone to bounce ideas off of and help you feel a

little more focused. There are some arrangements that haven’t

worked, some songs that haven’t worked, sounds at times, little

things that just don’t get me to one hundred percent satisfaction.”

That restlessness, again, is something Rupert Hine greatly

appreciated in the band. He recalls: “I do remember having a

chat — mainly with Neil, although the whole band were there

— about how much we admired David Bowie for being the

finest example of an artist who will risk losing half his fans —

and he often did — on each new album. But he always picked

up the same amount of fans who’d never bought a record of his

before, album after album after album, all the way through the

’70s and half of the ’80s, at least. I would speak to so many people

who said, ‘I’ve never liked a David Bowie record before, but this

new one’s fantastic — I actually went out and bought it.’ And

you know there’s one just like him who’s not bought it for the

first time. And Bowie would continue this process, which kept

him fresh and at the absolute top of his game for like fifteen to

eighteen years.

“Neil loved that idea,” continues Rupert. “With a band, it’s

much, much harder to do, some would say almost impossible,

certainly to do it to the degree that David Bowie did it. Rush

have done it, I think, probably more than any other band, in

trying that idea out, to keep themselves fresh. To make their

writing have new purpose. Neil particularly, who after all is the

textual voice of the band. He’s the one the responsibility falls on

each time to make sense of each individual song and the whole

album. It’s a contextual and very much textual parallel route.

“I’m not saying that Geddy and Alex haven’t contributed to

a lyric, but Neil often writes these completed lyrics, and they’re

presented to the band as a complete idea, which in and of itself

is unusual and really good. From a producer’s point of view, that

is the best, because right from the get-go you know exactly what

you’re trying to do with this song, what’s being communicated.

I hate when you’re working with a band that haven’t gotten the

lyrics together yet — ‘We’ve got a line and the chorus, which is

going to go blah, blah, blah.’ So we’re recording arbitrary parts to

a song that’s not yet saying anything.”

Given his bond with Neil over lyrics, Rupert figures it might

have been Peart who wanted him as the band’s producer more

than anybody else.

“Thinking about it now, yes. I know the idea originated with

Neil. Often the most conceptual discussions about the album

and its music — as opposed to its arrangement and production

— would always come from Neil. I would assume that’s because

he’s the man in charge of the words that come out of Geddy’s

mouth. The voice piece of Rush — the horn if you like — is

Geddy’s voice, but the motor is Neil. I feel that he is often driving

the band, the band’s ideology. It’s collective of course; sooner or

later, it’s collective. But I feel that the essences of change probably

start with Neil. They certainly felt like they did in the two albums

I worked on, but I’m imagining that’s probably always true.”

If Neil is the engine that drives the ideology of Rush, Hine

figures that “Geddy is the M.D. of the band, the musical director.

He’s involved in everything, even guitar solos and what have

you — always lovingly, never unpleasant or provocative in a bad

way. He would be the organizer, the equivalent of a tour manager.

That’s the pragmatic side. But to me it’s always, ‘What are

we trying to do with this record that I’ve been invited to be a

big part of? What’s the point of doing this record, apart from it

being #14 in your lifelong story? What are we going to do that’s

going to make this chapter really significant? What is it that you

guys want to say?’ And as soon as you use a word like say — and

I would all the time — you feel everyone’s looking toward Neil.

The voice of Rush is Neil. He was always at the epicenter.

“On the day-to-day stuff, it was Geddy, and Geddy is such a

lovely chap, a fantastic man to work with, bright-minded, sparkly,

very funny. I carry with me all the time his Jewish grandmother

voice, which is just to die for. And I’d say Alex has more fun

making a Rush record than the other two put together. He just

seems to be in the sandpit playing. That’s when he’s at his best. I

wanted to see him in the sandpit the whole time, you know, not

being watched over by his parents.”

The artwork Hugh Syme pulled off on the cover of Roll the

Bones is a stunner. It’s visually appealing, with the bold band name

front and center — as is tradition, no distinctive typography for

the band’s name is brought forward from the past, hence there’s

no attempt at establishing a logo. Still, Rush in mixed upper- and

lowercase letters built from black dice makes quite the impression.

Note also top to bottom, the dice get “darker” as the number

of white dots on each die decreases from six to two. This is set

within a wall of white dice, or “bones,” in slang parlance, named

because dice were originally made from ivory but also because of

their visual similarity to a skull. And, of course, there is a skull

on the cover: Hugh is always up for an extra joke for the eyes and

brain. The boy in Syme’s realist painting recalls young men pondering

their lot in life through Rush’s discography, including the

figure on the Power Windows cover and the protagonist in the

song (and video for) “Subdivisions” — as well as the vignettes

drawn up for “Tom Sawyer” and “New World Man.” Our young

Dennis the Menace type is booting a skull along a thin stretch

of sidewalk next to a waterway, which is rendered in the exact

same colors as the dice wall, reflective of it. The skull is one of

the most rollable bones, and it’s also the bone most laden with

meaning. It is in itself a memento mori, an object that serves as

a reminder of death, as is the entire scene, from the young boy

courageously flaunting death, to the weeds struggling to grow in

concrete, to the evocations of chance and randomness one can

derive from the dice.

Neil’s inspiration for the title was a Fritz Leiber sci-fi story

called “Gonna Roll the Bones,” which he had read back in the

’70s; there’s no direct influence of the story on Peart’s concept

or lyrics, but Neil had liked the phrase, so he jotted it down for

future reference.

Unsurprisingly, the opening track on Roll the Bones is one

of the album’s fastest rockers, and it’s quick to get rocking.

“Dreamline” also finds Neil almost immediately getting down

to the deep tissue and exploring the themes suggested in the

record’s title and cover art. He’s already leapt from the platform

and is examining the appeal of geographical exploration: the

road trip, the restlessness, the vitality slaked from getting out in

the world. Remarks about the fleeting nature of time and therefore

life are reinforced by Alex’s guitar picking, which sounds

like the ticking of a clock. Even Neil’s title, a made-up word, is

laden with enough meaning to serve as a microcosm for the song

as a whole, as well as the wider album.

“They have different satisfactions,” muses Peart. “‘Dreamline’

I really liked because I was able to write verses that were imagistic

and non-rhyming, freeing myself from my usual neatness

habits. Roll the Bones still remains really satisfying; it’s just a

good selection of songs.” The opening lines have Neil referencing

astronomy, which he was prompted to write about after

watching a PBS NOVA episode on satellite imagery after one

of his famed long stretches of cycling between gigs, this time

between Cincinnati and Columbus. The CD single artwork for

the song features three floating wishbones (one for each member

of the band?) over an ocean and sunset scene. So there’s bones,

a yearning, and a sense of the possibilities one gets from open

vistas. A wishbone is called that because two people are to grasp

the ends with their pinkies, make a wish and break it. Whoever

winds up with the largest piece gets his wish. Here again, there’s

the element of chance, rolling the dice.

“Dreamline” became a live favorite of the band’s for years to

come — the song was strong enough to serve as opener on the

Different Stages live album — as well as hitting #1 on the U.S.

Mainstream Rock Tracks charts. Indeed, even if Rush had no

ability to rock out at this juncture, “Dreamline” is built for live

execution, given its pause for the verses and attack come chorus

time. Again, even across this “heavy” part of the album, Alex’s

chords are behaved and tightly wound, Neil’s drums troubled

and trebly, and Geddy is playing a Wal bass. All three performers

are further emasculated by a similarly timid sound, that of

braying keyboard stabs, which, through lack of competition from

Rush, become the signature of the chorus, the highlight of the

song that is to be the highlight of Roll the Bones.

“‘Bravado’ is a song where I just loved how the music and the

words married,” says Neil of the record’s next track, a hypnotic

and measured dark pop song framed by Neil’s two-handed hi-hat

pattern. “That’s one of our more successful overall compositions

— arrangement, performance, all of that wedded together.”

Alex loves that his guitar solo on the track was a late-night

one-taker: laden with emotion, performed in solitude on his

Telecaster direct to tape, all the more perfect to go with Neil’s

serious lyric about people doing the right thing, personal heroism

from often unsung heroes, and Geddy’s steady and slow

delivery thereof.

Rupert thinks of this song with respect to the album’s sense of

emotion and fragility. “I suppose if you really are keeping things

as fresh as possible that means danger — it’s got to. I mean, to

be truly fresh is to go somewhere new and pushing that one foot

forward inch by inch or leaping a little in the way that Rush have

done, more than a little. So yes, there is a danger that probably

makes some of the moments have a certain fragility. I certainly

felt there was some emotional stuff that came out. I just referred

to the playing around in the sandpit side of Alex, which I found

quite emotional. There was a joy to that.

“People are a bit on the fence about Rush. They respect them

a lot, but they think they’re too technical, you know, not emotional

enough. And often Neil is somewhat narrative, with the

objective view rather than creating a cry from the inside. Those

aspects of Rush can keep them feeling like they’re a little distant

in the way they communicate. I thought we got through some of

that on ‘Bravado,’ which is still my favorite track of all the tracks

I did with them. It’s one of the least ‘Rush-like’ tracks. It’s sort

of a ballad, nothing terribly tricky. I get chills listening to that

track. I do. I love it; it’s gorgeously harmonic, melodic, expressive,

simple, but with meaningful text. That’s a set of skills that

perhaps showed some of that fragility.”

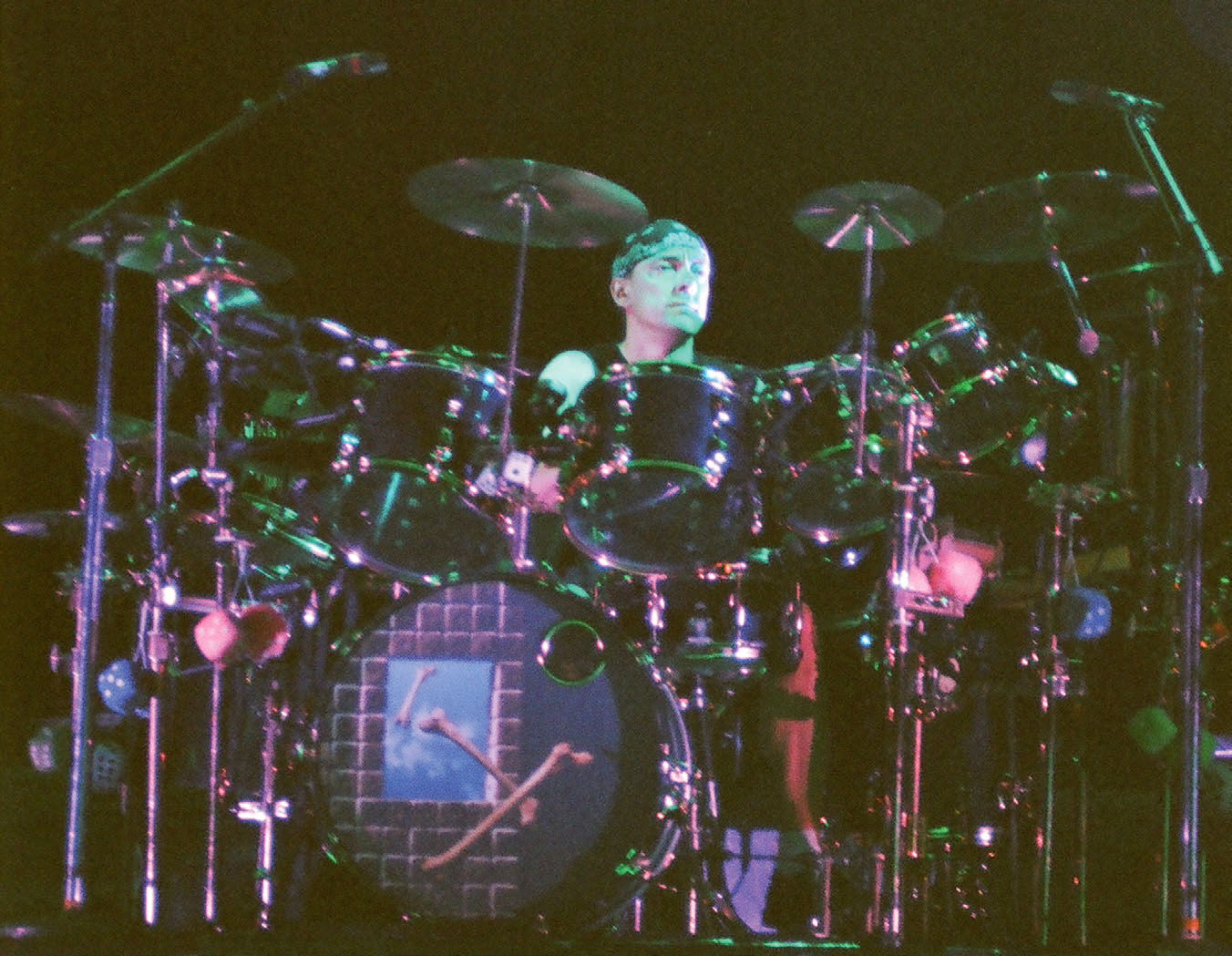

Hine was particularly impressed with Neil’s busy playing late

in the song, where he stretches out against yet another round of

the hypnotic, almost haunting chorus refrain.

“Yes, there were a couple of points, one in particular, where I

was listening in the control room. They were all playing together,

and Stephen Tayler, the engineer I was working with on both

those albums, I turned to him and said, ‘Are you checking out

what Neil’s playing? Can you figure out how many limbs he’s

got? Can you work out what’s playing what there? And it was

‘Bravado’ actually. It was impossible for just four limbs to play

this part if you check it out. My count was six limbs he needed,

not just five but six.

“So in the end we soloed everything to figure out how. Now

we’re not even checking out sounds or anything — we’re obsessed

by working out how on earth he was playing what he was playing.

And in the end, I had to get out . . . they were still playing, and I

had to go into the studio, I had to walk in front of him, I had to

stand in front of his drum kit and I had to watch. And I’m staring

at him, and that’s when I realized I still couldn’t tell. That’s only

happened once in my life — it was completely weird. It’s a trick.

He does these amazing, amazing trick things, that even when

you’re looking at him, it’s a sleight of hand, it’s magic.”

“I spent days on that drum part,” explained Neil, speaking with

Powerkick magazine. “Just over and over again. And that’s what

I’m saying about time being a luxury . . . we finished songwriting

and everything early, so I had time to rehearse my drum parts for

two weeks after that. I had a demo work tape that I would play a

song over and over until I was burnt out on it, and then I would

start on the next one. So I spent a couple of hours every day on

each song for like two weeks. ‘Bravado’ is a great example of that

because I orchestrated every section of it so carefully, but I also

left a lot of it free. A lot of the key things, a lot of the drum fills,

for instance, I didn’t allow myself to work out. Every time they

came, I just closed my eyes and let it happen. I didn’t want that

to become too big a part of the recording, because you can overrehearse,

and a part that’s played the same way too many times

can become stale. I wanted to leave a little bit of it feeling on edge.

“Over time, I think you learn that you want both, not just

a well-worked drum part and not just spontaneity, but both. It

shouldn’t be an either/or situation. I want to be both orchestrated

and improvised. It’s the way I start working on a song. I

think of everything that will fit in the song and try it out once,

and everything that I don’t like, gradually I will eliminate. And

then sometimes you do end up with less, because ultimately

that’s what the song requires and thus I’m satisfied by it.

“‘Bravado,’ for example, satisfies me to listen to and to play

as well,” continues Peart. “It’s deceptively simple perhaps to

someone who is not sitting down and trying to play it. It may

sound easy enough, but from my point of view on the level of

refinements — and the technical level too — it is demanding. To

juggle all those different approaches to verses and keep the tempo

smooth and all those other elements — including sequencers

when we play it live — makes it challenging. The consistency

of tempo during something like that becomes critical. Overall, I

don’t think it’s a question of ‘less is more’ but ‘better is more.’ You

keep searching for the best way to do it.”

Neil’s part was kept, but much else about the song was cut.

For this one, the guys had an embarrassment of riches, so many

quality parts, but in the end it was pared back to the sober and

resolute final product. Geddy calls “Bravado” one of his favorite

Rush songs ever, for its texture, for its emotion and for Neil’s

lyric, which he found poignant for its idea of paying the price

eventually, but in the present, not counting the cost.

-end excerpt

Driven: Rush in the '90s and 'In the End'