|

Classic Rock Magazine December 2021 Words: Dom Lawson |

Click Any Image to Enlarge

Rush’s 1978 album Hemispheres was one of the band’s most challenging records to make, but its stunning 36 minutes

are a clear indication of the trio’s chemistry. Geddy Lee recalls the album’s creation, and ponders its legacy.

More than 40 years have passed by since the release of Rush’s Hemispheres album. Not only is it one of their most widely beloved records, it’s also arguably the one that most thrillingly encapsulates the progressive abandon of the Canadian trio’s first decade together.

One of the most vociferously debated and lauded albums in Rush’s vast catalogue, its 36 minutes of pioneering prog is notorious for having pushed the three musicians to the limit of their abilities. Hemispheres is also often cited as the album that nearly broke Rush for good. Bassist/vocalist/keyboard player Geddy Lee takes us back to the trials, tribulations and, ultimately, triumph of the making of it.

In the spring of 1978, after finishing a gruelling world tour in support of the hugely successful A Farewell To Kings, Rush were too full of ideas to contemplate taking a rest.

“I think we were tired after the touring but at the same time we were also feeling pretty good,” Lee says. “Our range was expanding and we were feeling pretty ambitious at that time, which is evidenced in the crazy record that we made in Wales. We’d had a good experience working at Rockfield Studios before, and that left a good taste about the whole idea of recording in Britain again. When we arrived in Wales we were psyched, we were excited, but at the same time we were not superwell prepared. Although we had a lot of ideas, we hadn’t really hammered them out. So we found ourselves in a new situation, in a house not far from Rockfield. We’d planned to be there for a short time, and it turned into a much longer time, as everything to do with that album did. I’d say we were excited and a little bit nervous about the lack of preparation, but we were ready to dig in.”

Hemispheres’ reputation as a difficult album to make is probably well founded. With nothing concrete to lay down on tape, Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer/lyricist Neil Peart were under considerable pressure to conjure an album’s worth of material within a few short weeks. It is perhaps indicative of how potent the chemistry was between the trio at this time, that being woefully under-prepared seems to have pushed them to unexpected new heights. Not surprisingly, the bulk of the songwriting sessions were spent working on Hemispheres’ grandiloquent opener, Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres, the sequel to previous album A Farewell To Kings’ grand conceptual closer Cygnus X-1 Book I: The Voyage.

“Once the lyrics started coming together and we saw that Neil had this strong conceptual piece in his head, that sort of helped us to form a plan of action, and so I think it was quite an exciting way to work,” says Lee. “In the past we’d usually save one song on any album to write while we were in the studio, just off-the-cuff. Usually those songs would point us in a different direction for the next record – songs like The Twilight Zone [from 2112, 1976], Vital Signs [Moving Pictures, 1981] and New World Man [Signals, 1982], for example. But this was a lot more than just: ‘Let’s write a short, five minute tune.’

“We’d get together in this room in the house where our gear was set up, and we’d wrestle with the lyrics and put together melodies,” he continues. “We’d do all of that sitting around with each other, not necessarily plugged in, with Alex on an acoustic guitar, perhaps, and me on my bass, or sometimes we’d both write on acoustics. Then, with Neil, we’d hammer out a loose structure and then we’d take it to the next step, get behind the machinery and start playing it out until we were able to form the song. It was very much a threeway street in terms of coming up with the final version of the song.”

“We’d get together in this room in the house where our gear was set up, and we’d wrestle with the lyrics and put together melodies,” he continues. “We’d do all of that sitting around with each other, not necessarily plugged in, with Alex on an acoustic guitar, perhaps, and me on my bass, or sometimes we’d both write on acoustics. Then, with Neil, we’d hammer out a loose structure and then we’d take it to the next step, get behind the machinery and start playing it out until we were able to form the song. It was very much a threeway street in terms of coming up with the final version of the song.”

One familiar apocryphal tale about the making of Hemispheres posits that Neil Peart was struggling with writing lyrics and felt under immense pressure to deliver something special. But that wasn’t so, according to Lee, who says that continuing the Cygnus saga was fundamental to defining the direction the new music would take.

“I think [writing a sequel] made it easier for him, to be honest. I think he’d been thinking about this for a while and I think he knew where he wanted to go. It was just a matter of fleshing it out. He was probably more prepared lyrically than we were musically. Alex and I were really playing catch-up.”

Hemispheres is best known for its two magnificent bookends: the sprawling, joyously intricate title track, and the instrumental showboating blitzkrieg of La Villa Strangiato. But at a time when Rush were significant figures in the rock world and increasingly in demand on US rock radio, Hemispheres also included two of the band’s most succinct and enduring songs. The sub-four minute splendour of Circumstances, in particular, hinted strongly at another possible direction for these young masters to pursue, while also giving them a much-needed break from the arduous process of long-form songwriting.

“Yeah, that song was a bit of a holiday for us at that time, like: ‘Let’s do something short!’” Lee says, laughing. “The truth is, we don’t write more than we can use. If, along the way, a song doesn’t cut it, we just kick it out. We famously have no hidden tracks, because every song took maximum effort, and we didn’t see the point in putting in maximum effort for a song we had doubts about. So we decided that we needed one more song for Hemispheres, Neil had these Circumstances lyrics, and it became a great opportunity to do something different. Working on a side-long piece is so draining on many levels. You feel like you’re a slave to this concept. So anything that’s not like that feels way more fun.”

“Yeah, that song was a bit of a holiday for us at that time, like: ‘Let’s do something short!’” Lee says, laughing. “The truth is, we don’t write more than we can use. If, along the way, a song doesn’t cut it, we just kick it out. We famously have no hidden tracks, because every song took maximum effort, and we didn’t see the point in putting in maximum effort for a song we had doubts about. So we decided that we needed one more song for Hemispheres, Neil had these Circumstances lyrics, and it became a great opportunity to do something different. Working on a side-long piece is so draining on many levels. You feel like you’re a slave to this concept. So anything that’s not like that feels way more fun.”

Strangely, the song that became one of Rush’s biggest hits, both on radio and within their huge fan base, was Hemispheres’ skewed curio The Trees. A deceptively spiky tale, this disquieting fantasy about oaks and maples competing for the sunlight is an unlikely anthem, particularly given its rather unpleasant denouement. (Spoiler alert: the oaks get chopped down to size.)

“That song was one of the most fun that we were working on at that time, for sure,” Lee says. “We were surrounded by all that nature at Rockfield and it just made sense. I remember mixing it at Trident Studios. The engineer was a lovely guy. He was new to our music, and I remember him, after one runthrough of the mix, saying: ‘This is a nasty little tune, isn’t it?’ I said: ‘Well, maybe a little…’ But yeah, it was great fun to do that song. I loved the textures and the changes. It turned into one of our classic songs, I think. Surprisingly, I still hear it a lot travelling around America. When it first came out, I remember reading that it was a big radio song on some big FM station in Texas, and I thought: ‘Wow, that’s weird.’ It is kind of odd, but it’s sort of become one of our iconic songs.”

There’s something wonderfully subversive about the thought of hearing The Trees alongside Boston’s More Than A Feeling and Steve Miller’s The Joker on US rock radio rotation, but Lee attributes the song’s enduring success to Peart’s unerring ability to leave room for manoeuvre in Rush’s lyrical world.

“One thing that was always important to me as a songwriter, and regardless of what Neil was talking about, was I always felt the audience needed to have a choice,” Lee says. “You need to have the option of what you get out of the song. Whether it’s just a musical thing or if it’s the sound of the lyrics or whatever, that’s fine. You don’t have to understand it the way I understand it. And I don’t always understand it the way Neil understood it. I’m the first interpreter in that chain, and the audience are the next set of interpreters. That’s the beauty of art, it’s what makes it so alive. It should be communal and international, in a way. It should be open to interpretation.”

Is one of the benefits of playing progressive rock that it’s a genre that deals in so many ideas and concepts, that the unexpected is almost expected?

Is one of the benefits of playing progressive rock that it’s a genre that deals in so many ideas and concepts, that the unexpected is almost expected?

“That’s true. You can’t really write a rootsy country song about an egg-sucking dog [he’s referring to Johnny Cash’s Dirty Old Egg Sucking Dog] and keep any kind of mystery about what it’s about. I hate having things so explained to me sometimes. I was a huge Yes fan, and still am. Did I know what the fuck Jon Anderson was talking about most of the time? No! Does anyone? Does Jon? [laughs]. He had an idea, and only he really knows what he was trying to get across. I have my own takeaway from those songs, and I think it’s important to have that in music.”

Take a quick straw poll of any random gaggle of Rush fans, and it seems a safe bet that La Villa Strangiato would come out on top of a list of favourite tracks from Hemispheres (although it has to be said that there are only four tracks on it in the first place). Perhaps the ultimate showcase for the mind-bending musical interplay between Lee, Lifeson and Peart, it has weathered its 40-plus years impeccably and still sounds like what it truly is: three young, gifted musicians showing off and being joyfully inventive in the process. Thinking back to working at Rockfield, Lee notes that the sense of utmost urgency we hear on Hemispheres’ closing track is the result of a lot of blood, sweat, tears and insanity.

“I don’t really remember how the writing came together, but I do remember rehearsing the hell out of it beforehand. We really wanted to record it all in one go. It’s about ten minutes long and we wanted to do it in one shot. I remember writing it was great fun because the whole inspiration was, of course, these crazy dreams that Alex used to foist upon us every morning at breakfast. He’d start: ‘You’ll never guess what I dreamed last night…’ and the groaning would begin. But it was a really fun visual and musical exercise, constructing a soundtrack to an insane person’s dreams [laughs].”

“I don’t really remember how the writing came together, but I do remember rehearsing the hell out of it beforehand. We really wanted to record it all in one go. It’s about ten minutes long and we wanted to do it in one shot. I remember writing it was great fun because the whole inspiration was, of course, these crazy dreams that Alex used to foist upon us every morning at breakfast. He’d start: ‘You’ll never guess what I dreamed last night…’ and the groaning would begin. But it was a really fun visual and musical exercise, constructing a soundtrack to an insane person’s dreams [laughs].”

More than any other Rush track, La Villa Strangiato captures the wild energy that drove the band in their early days. You can almost hear them grinning as they switch moods and tempos with confidence, skill and ease.

“Doing something like that gave us licence to change as often as we wanted, to make the music as complicated as we wanted, to stylistically shift gears every thirty seconds. All of that is free and open to you. That’s the beauty of doing that kind of instrumental, you can make it up as you go along, you can decide what the script should be, and it doesn’t have to bear any relation to anybody’s idea of what an instrumental song should be. So it was superfun to do, and it’s still superfun to play live. It’s one of my favourite songs to play.”

Legend has it that you recorded more than 40 takes of La Villa Strangiato before nailing the final version. Is that close to the truth?

“I don’t remember how many takes it took, but I do know that we never got it in one go,” Lee says with a chuckle. “We’d set out to get it in one ten minute go but, again, our ideas were more solid than our ability to play them. So we settled for doing it in four pieces. We divided it into four, focused on those, and then used the good old magic of editing tape to stick them together into one cohesive piece. Those were the days before click tracks and that digital, metronomic attitude towards putting music together. So it was very much down to how you felt in the moment. Sometimes you’d get excited and you’d speed up, and sometimes that’s the way it should be. That’s why it feels so live.”

“I don’t remember how many takes it took, but I do know that we never got it in one go,” Lee says with a chuckle. “We’d set out to get it in one ten minute go but, again, our ideas were more solid than our ability to play them. So we settled for doing it in four pieces. We divided it into four, focused on those, and then used the good old magic of editing tape to stick them together into one cohesive piece. Those were the days before click tracks and that digital, metronomic attitude towards putting music together. So it was very much down to how you felt in the moment. Sometimes you’d get excited and you’d speed up, and sometimes that’s the way it should be. That’s why it feels so live.”

Originally planned as four-week stint at Rockfield, the Hemispheres sessions steadily turned into a much lengthier mission for all concerned. Due to both the complex nature of the music and the efforts required to perform it properly, and also to various technical problems that slowed the recording process, Rush and co-producer Terry Brown found themselves running out of time, and working around the clock to somehow piece this preposterous magnum opus together.

“At this time we’d developed this crazy footpedal system, kind of a version of MIDI before that existed. It arrived in time for the writing sessions in Wales, but it didn’t work,” Lee recalls. “We were so upset about that, and we spent way too many hours trying to make it work. We got some semblance of it working, certainly enough to be able to record. We really had a lot of fun working there, but the hours were getting later and later. We were sleeping until four in the afternoon and having breakfast at supper time, and then before you know it we were up until six in the morning again, going to sleep as the birds were tweeting and the sheep were baa-ing, you know? It was a crazy schedule and we ran out of time there. They had other people coming in, so we had to high-tail it. So we didn’t use the time we had set aside for mixing at Advision [studio], we used that to record vocals.”

Famously, Neil Peart introduced a gong into his percussion arsenal on Hemispheres. Meanwhile, Lee was experimenting with new effects pedals. Added to the intricacy of the songs themselves, is it any wonder that Rush struggled to get everything done in time?

Famously, Neil Peart introduced a gong into his percussion arsenal on Hemispheres. Meanwhile, Lee was experimenting with new effects pedals. Added to the intricacy of the songs themselves, is it any wonder that Rush struggled to get everything done in time?

“I think basically what we wanted was to record everything live on the floor. We wanted to record the songs in long pieces. Cygnus Book II was an adventurous piece of music to play and it was much more difficult than we expected, so in a way our skill set wasn’t as polished as our ideas were. So it was difficult. We had to raise our game. And that’s really what that album was all about,

raising our game.”

Another well-worn snippet of Rush mythology has it that the band struggled during the Hemispheres sessions because they were deeply unhappy about the state of their living conditions at Rockfield. Again, Lee dismisses that idea, noting that they had been there before, to record A Farewell To Kings, and knew what to expect.

“Oh, it was fine. I mean, you need something to complain about, right? Otherwise you start picking on each other. But I think we were okay there. We were happy there. I mean, we were there for far too long, and after doing two projects in a row we didn’t really want to go back there again. But we really liked the people at Rockfield. They took great care of us. We have very fond memories of Kingsley [Ward], who ran the place, and Otto [Garms], their in-house tech who was desperately trying to help me to fix my technical issues.”

With the four new songs down on tape, Rush left Rockfield and headed for Advision studios in London to add Lee’s final vocals. By this point the band were perilously over-schedule. And while they still felt hugely positive about the music they were making, the atmosphere in the studio was undeniably tense. Which was not the ideal environment for hitting some of the highest notes the singer has ever attempted.

With the four new songs down on tape, Rush left Rockfield and headed for Advision studios in London to add Lee’s final vocals. By this point the band were perilously over-schedule. And while they still felt hugely positive about the music they were making, the atmosphere in the studio was undeniably tense. Which was not the ideal environment for hitting some of the highest notes the singer has ever attempted.

“It was getting later and later, and people were getting a bit gnarly about the record and when it would be finished,” Lee remembers. “I was certainly a bit gnarly when I was doing the vocals. The difficult thing was that as we’d sketched these songs out, sitting around in a casual manner and humming the melodies – I hadn’t really sung them out against recorded, heavy tracks – when I came to record the vocals it was all in a very difficult key and it really pushed my range. That made me a very unhappy puppy. Unfortunately I gave our producer Terry Brown a very rough time while I was recording, because I was so frustrated. I was in that vocal booth at Advision, trying to hit those notes over and over again, trying to make them as perfect as I could, and it was tough. It was really up there!”

Those absurdly high notes have become a recognised part of Geddy Lee’s vocal repertoire. Looking back, however, he cites those sessions as an very educational moment in the band’s evolution as songwriters and album makers.

“Oh, it was a major lesson learned. It was a major faux pas,” he admits. “I think part of it was that I was angry at Terry, in a way, because I thought: ‘This is what producers are supposed to do, isn’t it?’ You know? Shouldn’t he have come in and said: ‘Do you think that’s in the right key?’ But that was something that almost never happened with Terry. Whatever we wrote, he made sure we recorded. He would of course question arrangements and make suggestions on structure, but I don’t think he ever suggested I try something in another key. It wasn’t until I started working with Peter Collins [on 1985’s Power Windows] that it became a matter of course and you did that with every song. He’d say: ‘Let’s try this song in different keys.’ ‘Let’s see where your voice goes.’ Or ‘Let’s see what works best.’ Those were things I was still learning when we made Hemispheres. So yes, lesson learned on that one.”

Can you still hit those high notes?

“For short periods of time, absolutely. When we went out on the R40 tour [in 2015], we realised we were going to play some oldies, like Lakeside Park, another song that’s way up in the stratosphere. I kept wanting to transpose the song down, and Alex kept saying: ‘No, you can do it!’ We tried different transpositions, and he was like: ‘They don’t sound good, Ged, come on…’ So when we got into doing it at rehearsals, yeah, I could hit those notes, and I managed to do it for the whole tour. So I can do it if I rehearse properly and take care of my voice. But I couldn’t do it night after night.”

“For short periods of time, absolutely. When we went out on the R40 tour [in 2015], we realised we were going to play some oldies, like Lakeside Park, another song that’s way up in the stratosphere. I kept wanting to transpose the song down, and Alex kept saying: ‘No, you can do it!’ We tried different transpositions, and he was like: ‘They don’t sound good, Ged, come on…’ So when we got into doing it at rehearsals, yeah, I could hit those notes, and I managed to do it for the whole tour. So I can do it if I rehearse properly and take care of my voice. But I couldn’t do it night after night.”

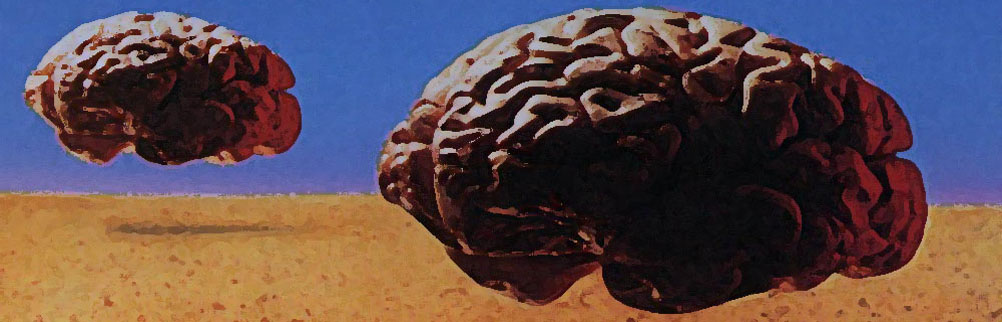

Hemispheres was released on October 29, 1978, resplendent in its none-more-prog artwork by regular Rush collaborator Hugh Syme. Artfully capturing the album’s lyrical preoccupation with duelling sides of mind and spirit, the cover’s giant floating brains added an extra layer of intrigue and eccentricity to what was already the band’s most ambitious and thoughtprovoking record to date.

“Yes, the artwork definitely helped,” Lee says with a grin. “Hugh was very much wanting to express the ideas that came out of Neil’s lyrics. He was really into that whole thing: what the songs were trying to say, and how that should be expressed somehow in the artwork. Neil and Hugh went to town, they’d run it by Alex and I and we’d give them our opinion. I think both of the chaps on the cover are Hugh’s pals. One was a ballet dancer and the other guy, I think, was a bank robber. I’m not sure if I’ve remember that correctly. But it’s a weird cover. It freaked people out. The brains were not received well by all. But it’s definitely very proggy.”

A surprising critical success, Hemispheres did not take off in quite the way that Rush’s record label bosses would have wanted, but its initial, solid performance in charts worldwide – including reaching No.14 in the UK – confirmed that the band were still heading onwards and upwards. For Lee, Lifeson and Peart, it was a case of sitting back and waiting for the fans’ responses to start trickling down to them. As far as the band were concerned, they had made a great, if challenging, new record, but there was no guarantee that everyone else would agree.

“I had absolutely no idea how people would take it,” says Lee. “I just thought people would think it was way too weird. We had no idea. I knew it would be a tough sell to radio, because these pieces were so long. But you can’t worry about that stuff when you’re doing it. I saw this interview with Robert Redford the other day, and he quoted TS Eliot, and Eliot said that it’s all about the trying, and what happens after that is none of our business. I’d say that sums up how we felt after making Hemispheres.”

Were you surprised by how well received it eventually was?

“Yes I was. It wasn’t initially super-successful, it was a slow-burn. But what surprises me to this day is that I have so many fans come up to me and say that they think it’s the ultimate Rush album. So it has become iconic, in a way, for our band, as a representation of our most complex period.”

“Yes I was. It wasn’t initially super-successful, it was a slow-burn. But what surprises me to this day is that I have so many fans come up to me and say that they think it’s the ultimate Rush album. So it has become iconic, in a way, for our band, as a representation of our most complex period.”

Just 15 months after the release of Hemispheres, Rush would casually redefine their entire sound, ushering in a new decade with the timely sheen of Permanent Waves. But while history might remember Hemispheres as a moment of transition, where Rush began to fully embrace music’s limitless potential, Geddy Lee remembers the album as an exhausting, if momentous, full stop at the end of Rush’s rise to prominence.

“It didn’t feel like a transitional record. It felt like the end of an era for me,” he says. “I felt that the side-long thing was getting predictable for me as a writer, and I wanted to bust out of that. In a sense it felt like saying goodbye to that period. I had ideas of where I wanted us to go. Songs like The Trees and Circumstances pointed in that direction. I wanted to tell stories, but I didn’t want to be weighed down by themes that had to keep repeating over a twenty-five-minute period. I wanted to be able to accomplish many more musical ideas over twenty-five minutes.”

Nonetheless, for many, Hemispheres remains the ultimate Rush album: 36 minutes of jaw-dropping, head-spinning, no-holds-barred prog rock, conjured from nowhere and delivered with ageless, life-affirming enthusiasm.

“I don’t know if I can ever possess the necessary objectivity to be able to see and hear what people see and hear in Hemispheres,” Lee concludes. “But I like to think that it’s the ambitiousness in the effort we put in. There’s something truly prog about that record, and I think fans of that genre really apreciate it.”