|

Rush Across the Decades, Book 1 by Martin Popoff May 12th, 2020 |

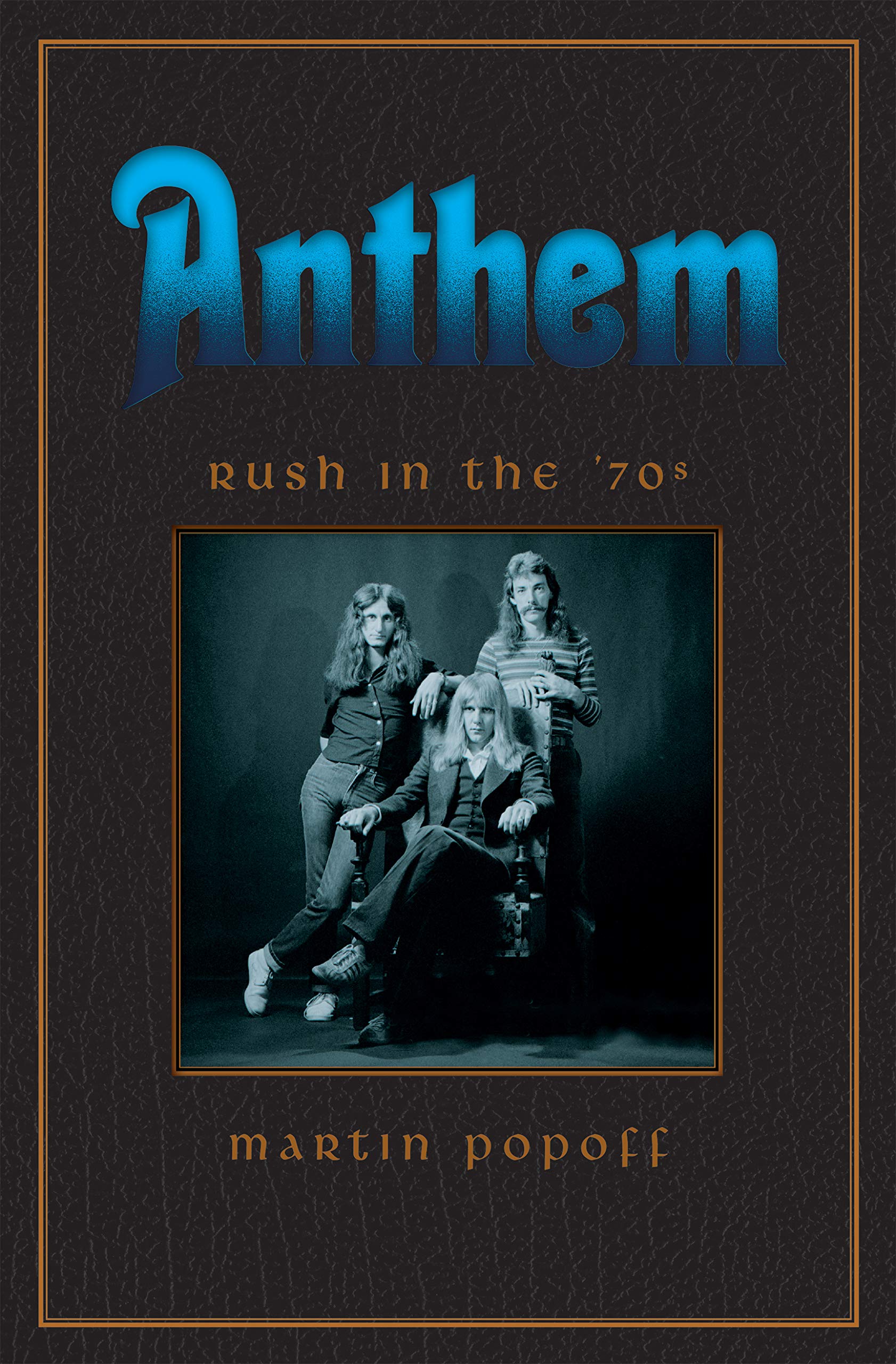

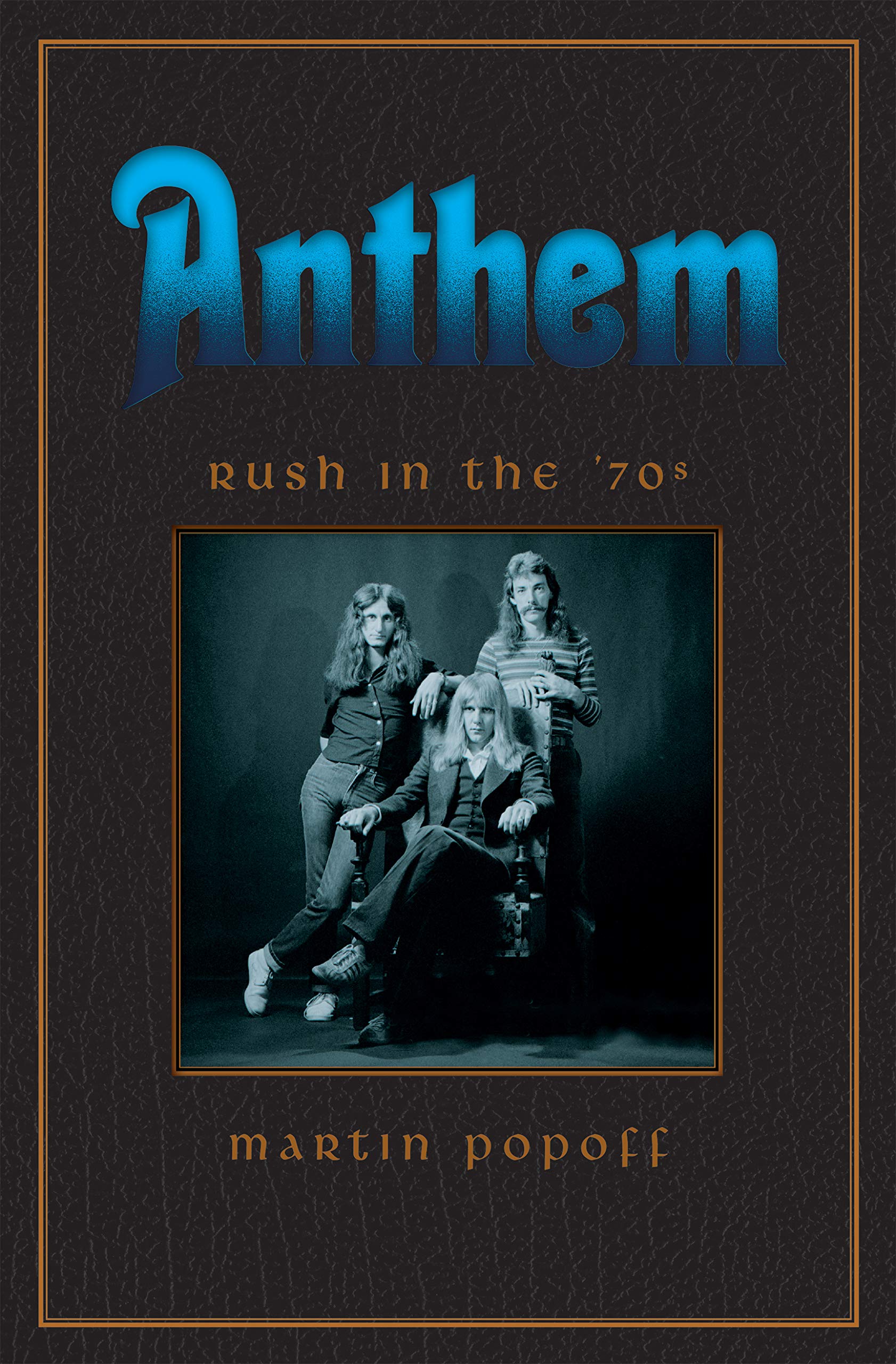

With extensive, first-hand reflections from Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, and Neil Peart, as well as from family, friends, and fellow musicians, Anthem: Rush in the '70s is a detailed portrait of Canada's greatest rock ambassadors. The first of three volumes, Anthem puts the band's catalog, from their self-titled debut to 1978's Hemispheres (the next volume resumes with the release of Permanent Waves) into both Canadian and general pop culture context, and presents the trio of quintessentially dependable, courteous Canucks as generators of incendiary, groundbreaking rock 'n' roll.

Fighting complacency, provoking thought, and often enraging critics, Rush has been at war with the music industry since 1974, when they were first dismissed as the Led Zeppelin of the North. Anthem, like each volume in this series, celebrates the perseverance of Geddy, Alex, and Neil: three men who maintained their values while operating from a Canadian base, throughout lean years, personal tragedies, and the band's eventual worldwide success.

"In his always compelling manner, Martin Popoff digs deep into the crucial first decade of rock's legendary trio. Brilliantly detailed and passionately presented, Anthem flows with all the confidence and capability of Rush's music itself. I literally couldn't stop reading this. Page after page, chapter after chapter, Popoff illuminates Rush's storied career with an infectious passion and precision. A remarkably thrilling, vivid account."

— JEFF WAGNER, MEAN DEVIATION: FOUR DECADES OF PROGRESSIVE HEAVY METAL

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter 1: Early Years

Chapter 2: Rush

Chapter 3: Fly by Night

Chapter 4: Caress of Steel

Chapter 5: 2112

Chapter 6: All the World’s a Stage

Chapter 7: A Farewell to Kings

Chapter 8: Hemispheres

Discography

Credits

About the Author

Martin Popoff — A Complete Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

The comparison is a lark — but it’s funny, so I’ll give it anyway.

Under the black country skies of Trail, British Columbia,

in the mid-’70s, heavy metal ruled. It was as big a deal

in my hometown as in the dual cradles of metal civilization —

Detroit and Birmingham. Where they had steel and car parts,

we had a lead and zinc smelter, an employer of thousands in our

small town and a satanic mill that sat on the hill, looming over

the city center. In fact, that’s where you went after high school if

you weren’t going to university; you went to work “up the hill.”

Okay, comparing Trail to the towns where Sabbath, Priest, the

Stooges and MC5 were created is laughable. Plus my dad was a

teacher, my mom was a nurse and I grew up wanting for nothing

in a spacious house built in 1970 by the family in the idyllic suburb

of Glenmerry. But me and my buddies were still all angry young

metalheads, and I’m pretty damn sure we were listening to Rutsey

’n’ roll Rush at eleven going on twelve before 1975.

So “Working Man” indeed, if not exactly for me and my

immediate circle. That song really connected in Cleveland, and it

made a hell of a lot of sense for the busted-up hard partiers working

at Cominco. In my late teens, running the record department

and selling stereos at a couple different stores, I got to know

quite a few of those people (from a wary distance). They were

scary and cool, and more than occasionally they would drop ten

grand on a pair of Klipschs, JBLs, Bose 901s or carpet-covered

Cerwin Vegas, usually powered by a new Yamaha 3020, much to

the delight of my boss Gordon Lee, who still runs Rock Island

Tape Centre forty-something years later.

Of course, all these guys were Rush fans too, cranking “Bastille

Day” in their Camaros and Mustangs (yes, Gord threw me in

the deep end as an installer) and pontificating over 2112 while

they nurtured their private pot stashes growing in the cupboard.

They knew about Rush because I sold them their friggin’ Rush

records but also because we had the quintessential rock radio station

in KREM-FM, broadcast over the border in glorious high

fidelity from Spokane, Washington, where they worshiped these

wise Canadian swamis of sound. In fact — fond memory — they

played the entirety of 2112 when it came out, and of course we were

all ready with two fingers to hit play and record as the sun set.

But there was another bed-headed gathering of beer buddies

poring over the seven Rush albums we will be celebrating in this

book, and that was the aspiring players. I was one of those. The

day I jumped in my purple ’77 “baby Mustang” (a Toyota Celica)

and drove seventy miles to Nelson to pick up my nine-piece set

of black Pearls, inspired equally by Neil Peart and Peter Criss,

was magic. (Forty years later, I got to show Peter the receipt as

he signed some records for me at my book table at Rock’N’Con

in London, Ontario.)

Indeed, this is why it was such a joy writing this book, remembering the camaraderie in bands, however short-lived,

talking over Neil Peart fills with Darrell and Marc, Geddy bass

lines with Pete and Sammy and Alex licks with Mark and Garth

— and yes, he looked exactly like Garth from Wayne’s World, and

I wasn’t too far off Wayne. Rush was our rarefied, mystical music

textbook, Neil and his wordsmithing challenging our brains at

the same time. (I’m sure for a long time, we thought Geddy was

scribbling all these fortune cookies.) Rush made you want to

excel on a bunch of levels at once, and I swear that was their

purpose for high school kids worried about what comes next.

Geez, man, they were perfect. Prog rock proper was too creepy.

Tales from Topographic Oceans may have well been the Moonies

coming to get you. At the other end, all our metal bands —

Sabbath, Purple, Nazareth, Rainbow, UFO, Thin Lizzy, Kiss,

Aerosmith, the Nuge and at the obscure end, Legs Diamond,

Riot, Angel, Starz, Moxy and Teaze — were friggin’ all right

with us. But Rush made you try harder. They politely asked to

pour your energies into something more positive. Eat right, use

those weights in the basement.

Neil was pushing the philosophy and literature at one end,

and as players, man, what they did for kids’ self-esteem is

immeasurable. We had a purpose, a hobby that was a neverending

hard nut to crack. And yet I gotta say something about

Rush: they made it just this side of attainable. I think if we’d got

the slide rules out and did the math on Close to the Edge, The

Inner Mounting Flame, Aja, Red, Brand X or Buddy Rich, we’d

have all hung it up. But Neil with his regular rolls down those

tuned toms? More often than not, building his beats with only

one of his two bass drums? Much of what Rush did . . . well, you

could get there as a kid. I could get there as a kid.

That’s a personal reminiscence of Rush in the ’70s, to be sure.

But from what I’ve gathered from friends all over the world (admittedly, most of them white men in their mid-fifties), it’s a

near-universal experience.

I want to tell you a bit about the history of this book. As you

may be aware, this is my fourth Rush book, following Contents

Under Pressure: 30 Years of Rush at Home and Away, Rush: The

Illustrated History and Rush: Album by Album. And since those,

there have been a number of interesting developments that

made me want to write this one. To start, only one of those three

books, Contents, was a traditional biography — an authorized

one at that — but it was quite short, and given that it came out

in 2004 before Rush was officially retired, it was in need of an

update. I thought about it, but I wasn’t feeling it, not without

some vigorous additions.

That, fortunately, took care of itself. In the early 2010s, I

found myself working with Sam Dunn and Scot McFadyen at

Banger Films on the award-winning documentary Rush: Beyond

the Lighted Stage. Anybody who works in docs will tell you that

between the different speakers and non-talk footage that has to

get into what might end up a ninety-minute film, only a tiny

percentage of the interview footage ever gets used, the rest just

sits in archive, rarely seen or heard by anyone. Long and short of

it, I arranged to use that archive, along with more interviews I’d

done over the years, plus the odd quote from the available press,

to get this book to the point where I felt it was bringing something

new and significant to the table of Rush books.

So there you have it, thanks in large part to those guys —

as well as the kind consent of Pegi Cecconi at the Rush office

— the book you hold in your hands more than ably supplants

Contents Under Pressure and stands as the most strident and

detailed analy sis of the early Rush catalogue in existence.

-Martin Popoff

CHAPTER 1: EARLY YEARS

"We didn't have a mic stand so we used a lamp."

No question that the Beatles were and still remain the patron

saints of rock ’n’ roll. And February 9, 1964, the first of the

band’s three consecutive appearances on The Ed Sullivan

Show, would provide the nexus of that sainthood: that night, the

Beatles inspired myriad adolescents to take up the rock ’n’ roll

cause, including the heroes of our story.

But if you wanted to drill down, get more hardcore and find

out who might be patron saints of playing, it wouldn’t be out of

line to bestow that title upon those heroes — Geddy Lee, Alex

Lifeson and Neil Peart and their Canuck collective called Rush.

Of course, Neil, “the Professor,” chuckling through his

Canadian modesty, would deem that premise absurd, citing the

likes of his personal saints of playing, perhaps folks like The

Who and Cream, maybe Jimi and his band, Led Zeppelin or

maybe “underground” origami rockers like Yes, Genesis and

King Crimson. But pushing back at Neil, one might point out to

the drum titan that time moves on. Over generations, waves of

bands and rock ’n’ roll movements ebb and flow. Film stars from

the ’30s and ’40s are forgotten, big band orchestras are forgotten,

doo-wop bands are forgotten, ’60s and even ’70s radio playlists

are ruthlessly pared down to what can fit on the back of an envelope

— no one cares what you think anymore.

And so, as time passes and the ’60s greats are forgotten, the

members of Rush seem poised to become the new “patron saints

of playing.” And maybe they’ll stay there. In the mid- to late

2000s, the world turned to pop and hip hop with more and more

music made by machines. If indeed rock died further through the

parallel precipitous contraction of the music industry, marked by

recorded music being made essentially free, then we might be

able to pick those patron saints once and for all.

As drummers are wont to point out, no parents ever had to

force their kid to practice their drums, and by side glance, this

is why the patron saints of playing are not some sensible choice

like Mahavishnu Orchestra, Gentle Giant, Kansas or Brand X. It

takes some fire in the belly, some excitement, some fuzz pedal, to

light up a teen and their dreams. And that is why Rush is the band

that wrote the manual for more of our rock heroes from the ’80s

and ’90s than anybody else. They inspired those who have made

all the rock music before the genre’s miniaturization a few years

into the 2000s. Debatable as it might be — and these abstracts, of

course, are — if the widest, most productive and beloved flowing

Steven Tyler scarf of rock history until the end of guitar, bass and

drums runs from, say, 1977 until 2007, then Rush songs are the

ones woodshedded most by the players who populate that time

span, the songs that advanced the capabilities of hundreds of your

favorite rock stars, making them good enough to be heard.

But before all that, the Beatles shot like a bottle rocket emitting

white heat around the world, and that included Canada,

where Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson (we’ll hear about “the new

guy” later) were politely taking notes in Willowdale, Ontario,

a vague suburb northwest of Toronto. The class chums were

barely teenagers when rock changed conceptually from individuals

to bands. And already there was set in place a maturity

and focus built of the duo’s Canadian experience, with which

to deal with the cultural sea-change rifling through school

lockers worldwide.

Gary “Geddy” Lee Weinrib was born July 29, 1953, in

Willowdale, so he was the perfect age to understand the get out

of jail free card slipped to him, one imagines, by Ringo. He also

had a brother and a sister in a family headed by two Holocaust

survivors, Morris Weinrib and Manya Rubenstein, now Morris

and Mary Weinrib of North Toronto.

“They both worked originally in what they called the ‘schmatta’

business,” explains Geddy, concerning his parents, “which was

on an assembly line, sewing clothes and things like that. But they

worked their way up to a lower middle-class kind of income and

raised me in the suburbs. So I was a product of suburban life.

Listen to the song ‘Subdivisions’; that’s where I grew up. It was a

bland, treeless neighborhood. A new subdivision.”

Geddy says that being one of the few Jewish kids around made

him stand out. “They bused us to a school when we first moved

to that kind of neighborhood, and, as a young kid, it was pretty

terrifying. It was a tough neighborhood. That part of Toronto

was just on the border of being transformed from farmland to

subdivisions, so it was in transition. You had the leftover mix

of different kinds of social backgrounds, so there were a lot of

pretty tough kids — what we called greasers back then — with

not much to do except beat up the new kids. So, it was an exciting

time. I hated living in the suburbs, and my first opportunity,

I got out. And I think a lot of kids that I hung out with felt the

same way. Everything was going on downtown. We wanted to go

downtown — we spent our time going downtown.”

“My husband had a sister in Canada, and we didn’t have

anywhere to go,” begins Geddy’s mother, Mary. “And she made

papers for us and we came here in 1948. My husband and I stayed

with her for a while; we didn’t have any trade or a profession, so

it was very hard in the beginning. My husband had a friend from

years before, when they were just children in school, and he volunteered

to teach us — and he was going to be a pressman, and

I was going to be a finisher, for clothes. So in about two weeks,

he gave us some lessons, and we learned every day. And then

another cousin got us into a factory. Garments. My husband was

making a dollar an hour, and I was making fifty cents an hour.

And after a while, I was so fast that they gave me samples to

work on, on piecework, so I was making more money.

“So we finally moved and had our own place, and two and

a half years later, my daughter was born. I remember when

we would look for places to live, the first thing we would say

was ‘We have a child.’ If you had a child, it was the hardest —

couldn’t rent anything. And after we moved, Geddy was coming,

and when we had two children, the landlord, this blond lady,

would not accept us. We didn’t have money for a down payment,

but my husband went to this society that helps people and they

lent us the money, and we bought a house, and we waited for

Geddy to arrive. I remember every room in that house; I had

rented every room just to make up for the five thousand dollars

we owed. And Geddy was born, and my husband was so excited

because he was a boy, and we already had a girl.

“And it was a nice neighborhood,” continues Mary, “on Charles

Street. It was a really nice neighborhood, easy. It was a mixture

of young and old people. Afterwards, we moved to Willowdale.

Actually, first it was Downsview, and then to Willowdale. Allan

was born in Downsview. My husband sold the house overnight:

we went to a wedding, and his cousin was there, and he said, ‘You

know, Morris, I have a customer for your house.’ It was a bungalow.

So my husband gave him an enormous price and said, ‘If

she’ll pay it, I’ll give her the bungalow.’ We came home from that

wedding, two o’clock in the morning, and his cousin is sitting in

the driveway and said, ‘Sign here.’ So the next day we had to go

look for a home, and then we went to Willowdale.

“Everybody knew everybody, and it was nice — nice neighbors,

great place to be because all the kids were the same age,

with a lot of friends all over. It was a nice neighborhood: shopping

was easy, everything was easy. I remember when we bought

a store in Newmarket and we used to drive to Newmarket, and it

was treacherous. There were no roads, there was nothing, everything

was muddy, and if it was raining, you could hardly get

through. So my husband used to say, ‘You’ll see, in a few years

all of this will be built up.’ And sure enough, a few years later

everything was built up.” Typical of her sunny disposition, Mary

Weinrib remembers Willowdale more positively than Geddy.

“Pretty boring,” says Geddy. “Not much to do. So that’s why

music became so important to us because we would go to each

other’s basements and listen to music, and everybody had different

favorite bands. That was the social life. There was nothing

much else. The occasional concert, drop-in center, that kind of

thing. When I was twelve, my father passed away. And we were

kind of a religious family, a Jewish religious family, and in that

kind of household, when a father dies, the son, the firstborn son,

is supposed to . . . has a lot of responsibilities in terms of the

grieving process.”

Morris had never fully recovered from injuries he sustained in

a Nazi concentration camp. As part of Geddy’s grieving duties,

he says that he attended synagogue twice a day, morning and

evening, for eleven months and a day, and he had to abstain from

rock ’n’ roll, even removing himself from music in school.

“There are still songs that were popular that year that people

talk about and everyone should know it and I go, ‘What?’” continues

Lee. “There’s just a gap in my learning. Anyway, when

that year was over, I kind of dove headfirst to try to catch up to

being a normal kid, to play with other guys in the neighborhood.

And I often wonder if that’s what really made me hungry to be

a musician, the fact that it was kind of kept from me for a year.”

His mother called Geddy a “great kid, quiet; he really had

a good sense of humor, and he was a happy child. And he was

actually very respectful since he was a child, good in school, had

lots of friends; he was very good. Until his father died. It was

hard. We moved, and two years later, my husband died. And

Geddy was, I think, about twelve. He was really a big help to

me because after my husband died, I was in shock. And then

we had a store, and two weeks after, I was thinking I can’t go to

that store. I can’t go. They used to give me all kinds of pills and

this and that. Once when I was really, really crying and Geddy

heard me, he came in and sat on my bed and he said, ‘Mommy,

I know why you’re crying. You don’t know what to do at the

store, right? Daddy would really want you to open the store and

try, and if you can’t make it, you know you tried.’ And the rest is

history. He left, took all those pills, called the girl who helps at

the store, because she had a key in Newmarket, and he said, ‘I’m

coming out.’ I just want to give you what kind of help this child

was. Even later the same year. It was December, Christmastime,

I needed somebody to come and help in the store. I had a couple

of girls, and Geddy volunteered. And all day long, he was at the

cash. He didn’t even want a lunch.”

Driving home on Christmas Eve, Mary decided that Geddy

deserved a present for working so hard. Geddy said that Terry

next door had a guitar for sale for fifty dollars. Once his mother

was over the shock, and as they arrived home from the store, she

had given him the money.

“We’re telling him he’s now the man of the house,” continues

Mary. “You’re now the man that is the head of the house. So this

kid, after about two or three months that I was at work, he said,

‘I’m so glad, I’m so happy, Mommy, that you are working and I

can go to school because I thought I had to go to work instead

of school.’ You see, his father was actually a musician when he

was young. In those years, there was no thing where you could

become a big star. If somebody needed a drummer, he was a

drummer at a wedding. If someone needed a guitarist, he was

a guitarist. When we were in Germany, we lived with an old

German lady and we had one room. And she had a mandolin,

and he always used to talk about music and this lady says, ‘Here,

have the mandolin. Play!’ So he used to, every morning, go under

my window and make up all kinds of songs with a mandolin.

And when we were coming to Canada, I said, ‘You’re not taking

that big thing with you?’ And now I wish I had it. So he takes

after his father, really.”

On Geddy’s religious duties after his father’s death, Mary

explains, “All year, he used to go to say prayers to his father, twice

a day, morning and evening. I had a friend who used to take him,

take him to school, take him at night, bring him home. Yeah,

he was really young. Actually, he taught himself his Torah, and

taught himself to say the prayer. A week before his bar mitzvah,

I called the rabbi and said, ‘Here, we’re having that bar mitzvah,

I don’t know if this kid knows anything, because we didn’t have a

teacher to teach him.’ But of course, the rabbi was sitting beside

me. I was crying for a big reason, here my heart went, and the

rabbi put his hand on my shoulder, and he said, ‘Mrs. Weinrib,

I wish I had your son’s gift. Your son has a gift from God.’ Who

would believe that? You know what I mean? I just thought [he

said this] because I’m crying.

“Even before, when my husband was alive, the first thing he

brought to the house was a piano. We didn’t have a stitch, nothing,

no tables, no nothing, and we were teaching Susan piano

lessons. One day, on a Sunday, the teacher came and she taught

them something new. And I invited her for tea, and all of a

sudden, we hear playing, and the teacher says, ‘You know, I have

to go and congratulate Suzie. She really did a good job.’ And we

walked in, and it was Geddy. And the teacher said to me, ‘You

can’t let this go. This child has a very good ear for music. You

have to give him lessons.’ And he was like ten years old. But at

the time, we could just afford it for Suzie.

“All teachers told me this, actually, so I knew. His father had

the same ear for music. This man, in the morning, woke up

with radio, went to sleep with radio, and in the store, the music

was blasting. And you know what? He used to make fun of the

Beatles. My husband used to say, ‘“Yeah, yeah, yeah” — with

this he’s going to sell records?’ Always when I hear the Beatles, I

remember what he used to say to me.”

Soon Geddy would be listening to the Beatles again, but in

the meantime, it was hard for him to miss out.

“Yeah, it was; it was very hard. He couldn’t have any. Maybe,

in my presence, he never listened to music on the radio. He was

really doing his thing because he had to go and say prayers. And

after the year, he really came out. He was himself. After a year,

you can start. Especially when he already had his guitar. Because

his father died in October, and I got him the guitar in December,

the twenty-fourth actually. And then I remember, he had to do

a year in enrichment class to catch up, which was in a different

district. And then the next year, he went to Fisherville Junior

High School, and sometimes he knew more than the teacher did.

Because he had this background already. And that’s where he met

Alex. He used to bring him home. I used to love Alex. He’s such a

nice, cute guy, very polite, very nice and a very good relationship.”

Indeed, comic relief for Geddy came from this new partner

Alexandar “Lifeson” Živojinović, born August 27, 1953 in Fernie,

British Columbia. “First time I ever became aware of Alex was

at R.J. Lang Junior High School; he was easily noticeable back

then because he was a bit of a teacher’s pet,” chides Lee. “I also

had a friend, Steve Shutt, who became a well-known hockey

player, and we went to school together, and he was one of the

few guys that I met in high school that actually was much hipper

than he looked. Steve was funny because he used to grow his hair

every summer when he wasn’t playing hockey, and as soon as he

had to go back to hockey, he used to cut his hair, so he was like

this hidden freak. We got along pretty well back then, and he

was the first guy who made me notice Alex.

“Because I was playing and looking for other people to play

with, he said, ‘Well that guy there is a good guitar player. You

should hook up with him.’ Steve would talk to me because he

knew I liked music, and I was playing an instrument, and he

would talk to me about this guy, Alex Zavonovich — that’s what

he called him; he mispronounced his name — and he said, ‘You

should call this guy up; you guys could jam together.’ So that

was the first time I became aware of him. But I didn’t actually

make contact with him until we were in the same class next year

in Fisherville Junior High. He was a funny kind of kid, a yuckit-

up guy, and he got me laughing. So we hit it off in school. Plus

we liked the same kind of bands, and there was the fact that he

was a guitar player. I was playing bass, so it was kind of a natural

fit for the two of us. We would all sit at the back of the class. I

think he was the first friend I had in that area where we kind of

got irreverent together.

“Anyway, so it was actually Steve’s suggestion that I hook up

with Alex. And then, I’ll never forget, the next year we were in

the same class, and he always wore this paisley shirt and had

his hair combed and always sucked up to the teacher, I remember

very clearly. But that’s how we met, and then we found out

that we were both musicians and eventually it led to us playing

together. He was very likable. He was very funny. He’s still to

this day the funniest human being I’ve ever known. He’s got a

charm about him, you know. When you meet him, you just like

him. So I liked him, and we became good friends.”

Alex’s parents, Nenad and Melanija “Milla” Živojinović, also

arrived in Canada after World War II; they first met in Yugoslavia.

“My father was kind of sent out to B.C. to work in the mines,

as a lot of Eastern Europeans were at that time,” begins Lifeson.

“My mother’s side of the family . . . my uncles wanted to look

for better work, so they ended up out in Fernie as well, and we

left when we were very young. I think I was eighteen months

old or two years old when we left — I really have no memory of

our time there. And then we moved to downtown Toronto and I

grew up there and in the north part of the city.

“I became really interested in music at around twelve and got

my first guitar. My parents bought me a cheap Kent Japanese

acoustic guitar. I think it was ten or twelve dollars. You know, it

had the guitar strings two inches above the neck, and they were the

thickness of telephone cords. But it was really exciting. I was just

so overwhelmed by music and the sound of the guitar. I listened to

the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles and all of that stuff

in that era. And the following year, I got an electric guitar, again a

cheap Japanese electric guitar, from my parents at Christmas.”

Alex had negotiated to get this guitar — his first electric —

in return for turning in a good report card. His parents, pleased

with his grades, kept their end of the bargain, although they had

to borrow the money to buy the instrument. Says Milla, “He

wanted to have a group with this next-door neighbor we had,

but nothing happened there. So we got the electric guitar. He

played constantly, in the morning, in the evening, after school,

all the time.”

Like Geddy’s, Alex’s upbringing was quite ethnic, not out of

step in a city and country built by immigrants.

“We ate very ethnic foods, all my parents’ friends were other

Yugoslavians, Serbs, Croats, a real mix. Typical for a workingclass

Eastern European family in Toronto, we couldn’t afford a

cottage or have that whole cottage lifestyle, which a lot of my

friends grew up with. It was very normal in Toronto to have a

place up north or east or west. The thing that we used to do was

go to Lake Simcoe, to Sibbald Point, and all the guys would play

soccer and all the moms would cook and unpack food, put out

the blankets. There was a museum up at Sibbald Point, and we’d

go to the museum and swim. And every weekend in the summer

was spent up there because it was free and you could drive up

there and there was plenty of room. I remember always stopping

for Dairy Queen on the way home. Very Ontario, absolutely.

“It was typically working middle-class,” continues Alex. “The

summers were spent playing with friends and running around.

There was school and hockey and winter sports, just like anybody

else. I’d say it was a very normal upbringing. My parents

were very hard workers: don’t complain about it, go do something.

I really respected my dad for that. And my mom was a

nurse for most of her life and worked at Branson Hospital for

twenty years or something and still does volunteer work. She

still tries to be very active. Yeah, it was a really great upbringing.

I certainly don’t have any bad memories of growing up.

“When I moved up to Willowdale from a central part of the

city, I was ten or eleven years old and John Rutsey was a neighbor.

He lived across the street, and we both had a great love for music,

and we played baseball and football. He had a couple older brothers.

We used to have great times doing sport-related stuff, but we

fell in love with music at around the same time, and he sort of

gravitated to drums and I did the guitar. In fact, we started a band

then called the Projection, which I still think is a great name. It

was a few neighborhood friends, and we all knew the same six or

seven songs, mostly Yardbirds, and we would play these parties in

basements. You didn’t get paid for it or anything, but we would

set up. We had small amps and basically no equipment, but we

would play these seven or eight songs over and over and over

again. It was really, really cool and I can still see it . . . We did one

gig — if I can call it that — in my parents’ basement and it was

dark and we had a black light and the whole deal. We continued

to do things like that and we kind of put a band together with

different people, but he and I were the core of it. At the same

time, I met Geddy that year in junior high school, in grade nine.”

Alex’s mother, Milla, fills in some of the backstory with

respect to how the family wound up in the East Kootenays of

British Columbia.

“I came to Canada in 1951, June 18, with my parents and my

two brothers,” explains Alex’s mother. “I was sixteen and my

brothers were fifteen and seventeen. My dad was of Russian

descent, and in 1949, Tito, the president in Yugoslavia gave the

ultimatum to people coming in from different countries to take

citizenship. And if they didn’t wish to take citizenship, they had

to move out. And my dad had a sister in New York he hadn’t seen

for twenty-odd years, and he decided he didn’t want to take the

citizenship; he wanted to move out. So we had to go to Trieste in

Italy, and we were there for six months, in Provogo camp.

“We waited to hear the quotas for immigrants, and they

were offering us either Australia, New Zealand or Canada. We

couldn’t go to the United States, even though we applied because

of my aunt. So then we decided to come to Canada instead of

Australia, which was too far, and my dad wouldn’t be able to see

his sister as much. And so we came and worked on the farm.

To be able to come to Canada, you had to come and work on

the farm. And we stayed on that farm for, I think, a little over a

month. We were actually very lucky that we didn’t have to finish

picking the sugar beets because that was hard. We’d just started,

and the owner of the land, he said, ‘I see you can’t work on the

farm,’ so he was kind enough to let us go.

“And then we met a Serbian friend and moved to a small

mining town. My older brother worked in the coal mine and

my younger brother worked in the sawmill and I worked in a

restaurant. I was washing dishes for twelve hours. And my dad

was an older man, and he was injured in the First World War.

He had one artificial eye, and he wasn’t that well, so he didn’t

work at all. But after a few months . . . there is a religion called

the Doukhobors. They’re Ukrainian, Russian actually, and my

dad being Russian, they asked my dad to teach Russian to their

children in school, and that was the only job he had for a few

months. And then I met my husband Mac, Alex’s father. He

came to work there in the coal mine after his wife passed away,

and after a year or so of dating him, we got married.

“And then a year later, Alex was born,” continues Milla.

“And then we stayed until Alex was about twenty months. I got

pregnant with my daughter Sally, and we came to Toronto. My

parents and my brothers were here. We moved in April 1955, and

it was beautiful, actually. We moved near Harbord and Bathurst.

And Sally was born after a month or so, and my husband was

looking for a job. And then after he found a job — he worked in

O’Keefe, you know, beer — we moved a few places. It was difficult

having children, and we moved when my parents bought

a house. We moved upstairs with them, and we stayed about

two years. Then we bought a little house on Glencairn, close

to Bathurst, and we lived there until Alex went to school there,

grade one and two, and then we moved to Pleasant Avenue.

“When he was in grade one or two, Alex was a little worrier.

When we bought the house, my husband got injured and he

was in the hospital having surgery. And he overheard me saying

that we didn’t have money to pay the mortgage. And he went to

school and his teacher, she asked him, ‘Alex, you’re so sad. What’s

happening?’ And he said, ‘My mom doesn’t have money to pay

the mortgage.’ And she wrote me a letter and he brought the

letter home and I was self-conscious when I was talking to people

on the phone, for him not to hear. Because he was a worrier.”

Despite financial hardship, Milla, like Mary, has happy memories

of the neighborhood. “It was nice; it was mixed. When we

lived on Pleasant, we had Jewish people. I think we were the only

Christians on that street. But where we moved, a street called

Greyhound, there were Italians, Chinese people, Canadians,

Greek people, so it was mixed nationalities. I can tell you one

thing — that I’m Canadian, I love Canada, and as soon as I

came to Toronto, I really enjoyed life. Being in Fernie, that small

mining town, I didn’t really; I was quite depressed there. Because

there was nothing to do. It was a coal mine, so everything was

dirty, and there was one theater, one bank and one restaurant.

But when we came to Toronto, it was so different. Especially

when we came. We came in May, from a town just on the border

of Alberta and British Columbia, and in May it was beautiful

weather and the flowers were coming out and it was just lovely.”

As for Alex, Milla says, “He was a very, very good child. I

was bringing them up to respect people, to love people, to not

have any hatred to any other nationalities. I come from a country

where there were Croatians and Serbians, but I never had any

of that either. I had a lot of Croatian friends. Alex was always

friends with different nationalities — I remember a Hungarian

little boy, when we lived down on Brunswick Avenue, near Bloor.

Alex was a good child. The teachers used to send a very nice

report about him. He was very calm, but when he was a teenager,

well, this was his dream: to become a rock star. My dream was for

him to go to school — and then he quit grade twelve. And then

he said, ‘Well, I’m going to go and finish the following year.’ He

went, and he was a counselor, the president there. He did very

well, and the teachers were really liking Alex, and they came over

once to our place and they talked very highly about him.”

Both Milla and Mary were against their two angels going

rock ’n’ roll. But who was to blame for the boys catching the bug?

Fortunately for familial relations, Mary didn’t blame Alex and

Milla didn’t blame Geddy.

“I liked Geddy,” laughs Milla. “To tell you about Geddy, I

remember talking to his mom. And his grandmother was a sweet

lady; she used to call me and say, ‘Is my Geddy there? Well, you

know what? He’s going with shiksa now.’ He was dating a shiksa,

a Christian girl. Nancy was a shiksa. She would get so upset.

And I would say to Geddy, ‘Your grandma is calling you to go

home.’ So we had fun with them. And then we started going to

concerts that they had in Toronto together.”

“Geddy brought Alex home one day,” recalls Mary. “And he

seemed to me like a nice, intelligent boy. Quiet, not like a wild

animal. And I liked him right away. And I still like him. Good

sense of humor, like Geddy, and they got along very well. The

rest is history. I remember one day I was going to tell something

to Geddy, early morning, and I walk into his room, and I see

blond hair on the floor, somebody covered up with blond hair.

And I’m thinking — a girl? And I close the door carefully, and

I think, wow, Geddy let this girl sleep on the floor. And I’m

going to work, and an hour later, I call Geddy — he’s up — and

I said, ‘Geddy, how can you let this girl sleep on the floor in your

bedroom?’ ‘Mum, it’s not a girl. If it was a girl, she wouldn’t be

sleeping on the floor.’ It was Alex! You see, Geddy loved his bed.

He could never go to a sleepover. His bed was his everything.”

Milla didn’t blame Geddy for sending Alex down the risky

rock ’n’ roll path. “I realized that this was what Alex wanted. I

mean, he was a self-learner. He never took any music in school,

any teaching from anybody. He just went on his own. And that

was another thing that I was very proud of. I knew there was

something he inherited from someone because he just did so

well by himself. The lyrics and all that, and the notes — he could

read well.

“But it was me more than my husband,” says Milla, on

attempts to steer Alex right. “His father, everything was okay with

him, very positive. I was a little bit worried about his future. If

he doesn’t finish high school, what’s going to happen? And if the

group doesn’t succeed, what’s going to happen with his future?

Because I tell you, I worked nights, I worked factories, I went to

nursing school in 1970 to finish nursing and worked hard, worked

in electronics and everywhere. And his father worked two jobs;

he was a plumber and an electrician, and he worked for Massey

Ferguson as a stationary engineer, second class, for twenty-five

to twenty-six years. Plus he went on his day off and worked. So

I think that’s why Alex always, always respected hardworking

people. And today, that’s why sometimes I say to him, ‘I’m fine.’

He will always ask, financially, to help me. I would say, ‘I’m fine.’

He would say, ‘Mom, you worked so hard; I just want you to be so,

so comfortable.’ His father passed away five years ago [this interview

took place February of 2009], and he respected him so much

because of that, of that hardworking. He loved him so much too.

And that hard work. And that’s how, you know, myself as a child,

as a teenager before I came [to Canada], I went to school and I

had to work too. We wanted him to be something, to have education,

and well, he chose something else, and he did very well.”

Alex knew the value of non–rock ’n’ roll work as well. Like

Geddy helping out his mom in the store, Alex did the kind of

work teenagers resent but then later look back at and realize was

character-building.

“Yeah, I worked at Dominion for a while, in the meat department;

that was in grade ten, just exactly the time we started the

band. And then I also worked with my dad. He worked many

jobs. He was an engineer at Massey Ferguson, and he had his

own plumbing business, like a one-man plumbing business. But

he would take me out. In fact, later on, when I still worked with

him, and we were playing the Gasworks and all those clubs in

the early ’70s, I would go out and help him from time to time.

He would pick me up in front of the Gasworks at one thirty

in the morning when we finished playing, and I would go with

him and we would work all night on some plumbing job, and he

would take me home at eight o’clock in the morning and I would

completely collapse until five o’clock in the afternoon and then

head down to the gig later that evening. And then he would do

the same thing.

“And I tried my best to get out of that whenever I could

because it was always hard. Yeah, those two were the main little

jobs that I had. There were always things around the house that

I got volunteered for. But you know what? It was a source of

a little bit of money and it paid for the rent of the Marshall

amp and gas for the van and things like that, so we all pitched

in. Because those early days, we really didn’t make any money.

Maybe a hundred dollars, one fifty, and even earlier than that,

fifty dollars — the first gig we played was ten dollars. Although

ten went a long way in 1968. Well, not that long.

-end excerpt

Anthem: Rush in the '70s