|

|

|

There are 24 active users currently online.

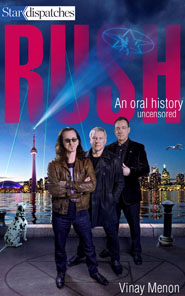

Rush: An Oral History

Toronto Star Newspapers

May 2013

by Vinay Menon

Click Any Image to Enlarge

With thanks to RushFanForever for providing this article.

Contents

Introduction

1. The Restless Dreams of Youth 1965-70

2. They Call Me the Working Man 1971-74

3. Constant Change Is Here Today 1974-81

4. All This Machinery Making Modern Music 1981-96

5. The Innocence Slips Away 1997-2001

6. The Men Who Hold High Places 2002-13

The measure of a life is a measure of love and respect,

So hard to earn, so easily burned.

In the fullness of time,

A garden to nurture and protect ...

The treasure of a life is a measure of love and respect,

The way you live, the gifts that you give.

In the fullness of time,

It's the only return that you expect.

- "The Garden," Clockwork Angels (2012)

Introduction

No band has become more successful by caring so little about suc�cess.

That's just one of the contradictions of RUSH, the power trio that was born in 1974. Since they first played together inside a drab studio in Pickering, Ont., RUSH has been on a musical journey with no map, in the middle of a story with no foreseeable end.

That's just one of the contradictions of RUSH, the power trio that was born in 1974. Since they first played together inside a drab studio in Pickering, Ont., RUSH has been on a musical journey with no map, in the middle of a story with no foreseeable end.

Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart are always looking ahead, even when talking about the past.

And what a past they've had: 20 studio albums, eight live discs, more than 43 million records sold. RUSH ranks third for most consecutive gold or platinum studio albums by a rock band, be�hind only The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

On the strength of tracks such as "Fly By Night," "Closer to the Heart," "La Villa Strangiato," "The Spirit of Radio," "Tom Sawyer," "Limelight," "Red Barchetta," "Subdivisions" and "New World Man," they have cultivated a global following that is united in fe�verish devotion to the prog rock demigods. The complex arrange�ments, the scorching riffs, the virtuoso musicianship, the almost pathological need for constant reinvention, the lyrical meditations that are at once philosophical and quotidian, all of this has pro�duced a strange kind of alchemy.

Most bands have fans. RUSH has kindred spirits.

How did this happen? How did three Ontario lads get their first musical instruments around the age of 12 and then, about eight years later, begin to rewrite the rules of rock by shrugging off all commercial imperatives?

-

The walls at SRO/Anthem on Carlton St. in Toronto, the band's management headquarters for four decades, are festooned with gold and platinum records. To paraphrase a song lyric, these are the glittering prizes that arrived with no compromises.

RUSH has always done it their own way.

The office belonging to Ray Danniels - the band's manager since 1969, when he and they were skinny teens with big dreams - looks like a RUSH museum, crammed with framed concert tickets, memorabilia and pictures.

On a cold afternoon in March, vocalist and bass player Geddy Lee ambles into this office, a coffee in hand, and patiently talks me through the past 40 years. Even in those early days, when their prospects seemed bleak, music was the only plan.

"I had no idea what else I would do," said Lee, now 59. "I think that's a function of youth. At this age, I'd probably be much more practical. But at that age, thankfully, you just blindly move for�ward."

A few days earlier, in a diner on Bloor St. where he occasion�ally takes his grandchildren, guitarist Alex Lifeson arrived with his own candid memories, which he shared while nursing a pot of green tea.

To get drummer and lyricist Neil Peart's erudite take on this brotherhood, I flew to Los Angeles and then drove to Oxnard, California along the Pacific Coast Highway, parts of which were closed that morning due to a landslide.

With his vintage Aston Martin parked out front, Peart was en�sconced inside a dark studio, not far from the factory where his custom drums are built. We sat on a leather couch, facing his elab�orate kit, and his eyes sparkled while reminiscing about The Gene Krupa Story, the 1959 biopic about the American drummer that first awakened his own interest in percussion.

"All three of us really became galvanized by the power and free�dom of rock music," Peart said, at the start of our interview. "What a great time to come of age in the mid-to-late '60s."

-

On April 18, 2013, RUSH will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. While there have been no shortage of cultural acco�lades - Order of Canada (1997), Canada's Walk of Fame (1999), a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (2010), the Governor Gen�eral's Performing Arts Award (2012) - this one feels different, es�pecially to the kindred spirits who've long complained about the band's conspicuous absence from the hallowed corridors of the rock shrine.

On April 18, 2013, RUSH will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. While there have been no shortage of cultural acco�lades - Order of Canada (1997), Canada's Walk of Fame (1999), a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (2010), the Governor Gen�eral's Performing Arts Award (2012) - this one feels different, es�pecially to the kindred spirits who've long complained about the band's conspicuous absence from the hallowed corridors of the rock shrine.

In typical fashion, Lee, Lifeson and Peart will head out on tour five days after the induction ceremony in Los Angeles. In retro�spect, the band's name seems remarkably precise: they seem inca�pable of slowing down.

To understand this trajectory, from playing high schools in Southern Ontario to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, from those endless days as the opening act in small theatres to headlining sold-out stadiums across the planet, I interviewed more than two dozen insiders - spouses, siblings, parents, managers, record ex�ecs, long-time crew members - who are as much a part of the story as the band itself.

From these interviews, an oral history was stitched together, a framework of the past 40 years, buttressed with memories and an�ecdotes, reflections and insights of a band that continues to exude an honesty, integrity and loyalty that seems entirely at odds with the music industry.

What happened offstage in those early years? How did the band cope with the early trappings of fame? How did they nearly throw it all away? How did the need to innovate, to explore new terrain, cause tension in the studio? What happened after unimaginable tragedy nearly caused them to disband? What is the secret to the success they still don't care about? And most important, how do they remember moving forward, blindly but with eyes wide open, during this musical journey?

In the pages ahead, they will tell you.

The Restless Dreams of Youth

1965-1970

Geddy Lee: I grew up in a suburb of Toronto, as did Alex. He was a child of Yugoslavian immigrants. And I was a child of Holocaust survivors. When I was 12, my dad passed away. And in the years following that, my mom was working a lot. She took over my dad's store and was running it in Newmarket.

Alex Lifeson: I was 12 years old when I started playing guitar. I got a very inexpensive acoustic guitar from my parents for Christ�mas, a Japanese guitar called Kent that they paid $10 for. The fol�lowing year, I got an electric guitar.

Melly Zivojinovich (Alex's mother): He came home one day and said, 'Mom and dad, if I brought you a good report card, could you get me an electric guitar.' My husband and I looked at each other and said, 'Yeah, sure.' Well, he brought such a good report card.

Geddy Lee: I had a neighbour who was selling a guitar that had two palm trees painted on it. I thought it was the most beautiful thing in the world.

Mary Weinrib (Geddy's mother): He was working with me in our store from morning till night and it was Christmas Eve. We were driving home and I turned to him and said, 'What can I buy you as a gift? You were so good all day with me.' He said, 'Mom, next door, there's a guitar.' I don't remember if it was 50 dollars or 20. I know I said, 'So much money?' But when we got into the driveway, I took out money and said, 'OK, go get the guitar.'

Neil Peart: I started drum lessons at age 13. School for me up until then had been easy and successful. Then drums came along and I was not interested in anything else in the world anymore.

Glen Peart (Neil's father): If he took on something, he wanted to know all about it.

Neil Peart: They had a set of Rogers drums in the studio where I took lessons, a beautiful set of little grey ripple Rogers. I dragged my dad there one day to look at them and lobbied my mom. My dad agreed to sign for the loan. He wasn't going to give me the money or buy me those drums. They were $750, I still remember. And the payments were $32 a month and I had to make those pay�ments. With mowing lawns and a little bit of money from gigs, I was able to do that.

Glen Peart: He really wanted that drum kit. So I went up and visited with his teacher and said Neil had aspirations of doing more and whether we should invest the money in the drum kit. And the teacher said, 'Yes, I definitely think you should. He has a talent and a feel for the drums. You should help him out as far as he wants to go.'

Geddy Lee: Music was really one of the first things I found as a kid that I seemed to have an aptitude for. I was able to listen to songs and figure them out. I had never been much of a sports kid. I was really good at watching television. That was one of my true skills as a child. So this was the first thing that really grabbed me.

Alex Lifeson: I was at Pleasant Ave. public school. I remem�ber in Grade 6 going to the library and they had a record player and headphones and classical records. I just felt really connected to music.

Melly Zivojinovich: I think it's sort of hereditary. On his fa�ther's side, there were great musicians. His father's uncle used to play for Russian princes. My father also used to be a great singer.

Neil Peart: I had 12 LPs. I'd line them all up and change them. I also had an AM radio, a clunky pink steam radio beside my drums. I'd play along with the radio every day.

Geddy Lee: I started playing in a little garage band. I was on guitar at the time. Then the bass player's mother wouldn't let him be in the band anymore. That's how those things worked back then. So we needed a bass player and they said, 'Why don't you play bass?' I identified with the bass almost immediately. I started listening to albums differently, trying to pick up the bass lines.

Alex Lifeson: In the summer of 1967, everything just kind of exploded. It was all about music. We started a band called The Pro�jection. John Rutsey (original RUSH drummer) was in that band. It was just a basement band. I can still visualize what that was like, our little setup in the basement and how horrible we played but how exciting it was.

Alex Lifeson: In the summer of 1967, everything just kind of exploded. It was all about music. We started a band called The Pro�jection. John Rutsey (original RUSH drummer) was in that band. It was just a basement band. I can still visualize what that was like, our little setup in the basement and how horrible we played but how exciting it was.

Neil Peart: One unique thing about our generation is every�body I knew played in a band. There were at least five or six com�plete bands around my grades of high school. We could get work every Friday and Saturday night at the YMCA or the roller rink.

Alex Lifeson: In the summer of 1968, John and I got a little more serious and met a bass player named Jeff Jones, who went on to play with Tom Cochrane and Red Rider. We got this gig at a church basement. It was like a drop-in centre called The Coff-In. There were maybe 10 or 15 people there. We got another offer to play there a week or two later. Jeff couldn't make it because he had another band he was playing with.

Geddy Lee: I had met Alex at school. He was in a band called RUSH. He would call me all the time to borrow my amp.

Alex Lifeson: I used to borrow Ged's amp because I didn't have my own. Ged and I were in school together and we played all the time. That whole year, we played at least a few times a week. Usu�ally we'd go to his place and just jam after school till dinnertime. So I called Ged and asked if he could sit in. We had this gig and it was paying $10. It was good money.

Geddy Lee: It was just exciting to play a gig and make money. It was a way for a nerdy kid to stand out.

Alex Lifeson: So he came out. It was a small crowd on a Friday night. But it was great. We all felt something. We went to Pancer's Deli afterwards and started to plot our dominance of the world over French fries, gravy and Coke.

RUSH started playing at high schools around Southern Ontario. In 1969, they met Ray Danniels, a teenager who had left his Water-down, Ont. home and moved to Toronto with dreams of breaking into the music business.

Alex Lifeson: Ray kind of hung out with Sherman & Peabody, a band at that time. When we met him, he was kind of a runaway. He said, 'Do you guys need a manager?' And we said, 'I guess so. We're a band now so we must need a manager.' We didn't know where it was going to go.

Ray Danniels: I didn't have a master plan. As a 16-year-old kid, the master plan was to stay alive and make a job out of this. I certainly did not expect to be riding in the back of a limousine anytime soon.

Geddy Lee: We were going to be musicians. There was no back up plan.

Allan Weinrib (Geddy's younger brother): My mother was al�ways kind of freaked out by it. She would say, 'Where is this really going to go? He's just wasting his time.' She didn't really see where it could all go at that point. There was always a certain amount of anxiety.

Mary Weinrib: I was very worried about it. I didn't want to lose him. First of all, he was a good student. He was in enrichment class! I thought he was doing this as a recreation thing.

Geddy Lee: She had a very hard time, bless her heart. As a teen�ager, she had gone through hell and back in the war. She came over to start a new life here in Canada and then lost her husband, which broke her heart. She's never really gotten over that in some ways. And here's her son running off half-cocked with these crazy guys, growing long hair, playing this stuff that doesn't sound like any kind of music she could recognize.

Mary Weinrib: Every day he used to have his little friends com�ing into the basement and playing all this and all that.

Geddy Lee: She just thought we were out of our minds. She was sure I would end up a drug addict or down the drain.

Mary Weinrib: One day, I had a big discussion with him. I was worried about the drugs. He said, 'Mom, nobody can make me do anything if I don't want it.' And he said, 'Don't worry. I'll never let you down.'

Melly Zivojinovich: I feel so embarrassed. I used to put Alex down. I would say, 'You're never going to get anywhere. You just need to continue school.' And he said, 'Mom, one day, you'll see, you're going to have good life. I'm going to be making money.' And I said, 'Oh, right.' I did apologize later. But like every parent, you want the best for your kids and education. And at that time, the music lifestyle was kind of scary.

In St. Catharines, Ont., drummer Neil Peart was in a band called J.R. Flood. He tried to convince his band mates to move to a bigger city. When they declined, he set out for London on his own.

Neil Peart: My dad built me a wooden crate for my drums and my LPs. And I moved to England at 18 years old and lived there for a year and a half. It became the most profound experience of my life.

Glen Peart: At that time, all the music that Neil loved was com�ing out of England. His idol, of course, was Keith Moon of The Who. He said, 'Well, if I have to go on my own, that's the place I want to go.'

Neil Peart: It was the first time I was away from home on my own. I had $200, arriving in England on a one-way charter ticket. Sink or swim, basically.

Glen Peart: His determination overrode any fear that we had.

Neil Peart: It's not that I thought I was that great or too good for St. Catharines. I just wanted it so bad. That's what carried me to London and made me knock on the doors of all these manage�ment offices. I wasn't received rudely. But neither was Jethro Tull looking for a new drummer that day.

While auditioning and picking up a bit of session work, Peart worked in retail shops on Piccadilly Circus and Carnaby St.

Glen Peart: We had a chance to go over there and visit him. We talked to him at that time and he didn't have any real prospects. He was managing a souvenir store in downtown London. We spent four or five days with him and I said, 'Neil, if you're going to end up just managing a store, I've got a parts department back at the farm equipment dealership that needs a manager.'

Neil Peart: I thrived in the everyday work environment, which gave me a confidence that a lot of young musicians don't have. That, yes, I can do something else. Forever after, I was less willing to compromise. I felt less threatened by any of the business side trying to exert pressure on me. I knew I could do other things and it did make me much more stubborn about music. One time when I was living in England, when times were tough, a friend said, 'Look we have a job at a cocktail bar, playing for a bunch of businessmen for �20.' I tried it that one time and it was so awful. It was the only job I ever walked out on. It was a bunch of big fat English guys in 12-piece suits shouting and yelling while we played cocktail jazz. I said, 'Sorry, guys. I can't do this.' Music isn't for sale. It doesn't have to be.

Glen Peart: We can't explain him. His mother and I say, 'We don't know where he came from.'

They Call Me the Working Man

1971-74

Studio albums: RUSH

Pegi Cecconi (SRO/Anthem Management Team): I first started at SRO in March, 1973. But where it really started was in 1971. Ray Danniels used to be a booking agent and I used to be the high-school buyer. I was in a town called South Porcupine, Ont. I used to buy the bands and he would call me. But I wouldn't buy RUSH because I could get a four-piece for the same amount of money!

Alex Lifeson: We only played a few times a month. It wasn't until the drinking age was lowered to 18 in 1971 - that was the year we turned 18 - that we went from three gigs a month to six a week with matinees on Saturdays in some cases.

Ray Danniels: It literally changed overnight. Suddenly I had all the bands the bars wanted. But the guys in RUSH were my first love. They were my friends. The other things I was doing with my agency were paying the bills so I could keep doing this thing with RUSH.

Alex Lifeson: I remember riding with Ray on a little Honda 90, putting up posters on telephone poles for these gigs that he booked. I think we were always his first priority but not his mon�eymaker. We really didn't make any money whereas he had other bands that were more pop-y and made money as the agency grew. But he always believed in us.

Pegi Cecconi: Ray always knew they would be the band.

Alex Lifeson: When I was in school, the agency started doing really well. Ray got a nice apartment on Balliol (St. in Toronto). The door was always open to come hang out, order a pizza, maybe smoke some pot. He was more than just a manager. I think because we were close in age, it was more of a friendship right from the start.

Ray Danniels: We were all basically high school dropouts or just finished high school and that was the extent of our education. So the plan was to just keep this going. We were driven.

Alex Lifeson: We toured all through Southern Ontario, doing a week here, a week there. We worked very steadily through that pe�riod. But we wanted to make a record and nobody was interested.

Geddy Lee: In those days, because we were much more of a live band and we hadn't really had any recording experience, it was more a matter of bringing people to see us at The Gasworks or Ab�bey Road Pub, places that are now long gone. We'd play these bars and Ray would keep bringing these record execs out.

Geddy Lee: In those days, because we were much more of a live band and we hadn't really had any recording experience, it was more a matter of bringing people to see us at The Gasworks or Ab�bey Road Pub, places that are now long gone. We'd play these bars and Ray would keep bringing these record execs out.

Ray Danniels: There were two or three people who liked it and were maybe close to signing. But I can't say it was easy. Nobody came in and said, 'These guys are going to be the next Cream.'

Alex Lifeson: They actually all said the same thing: 'It's too noisy. It's too loud. It's too heavy. Your singer's voice is really an�noying.' Those were the comments that we got from everybody at the start. So it became incumbent on Ray and his partner at the time, Vic Wilson, to put up the money and start a label so we could make a record.

Geddy Lee: Our label was called Moon. That's how we got our first recording experience. We weren't a singles band. We were an album band. We wanted to do an album. That was always our dream.

Alex Lifeson: We recorded that first album in between gigs at The Gasworks. We'd tear down our gear after a set and then go to Eastern Sound, which was on Yorkville. We recorded overnight at a special rate when the studio wasn't busy with session book�ings. We recorded and mixed in a couple of days. Unfortunately, it sounded like it.

Geddy Lee: We were working with this English engineer. You have to remember, we had no money. (The engineer's) back was up against the wall. He mixed the whole first album in the time it took for us to play three sets at The Gasworks. It was so disappoint�ing to hear. We were just bummed out. For us, it was a failure. It sounded rinky-dink. We couldn't release it. We were embarrassed by it. That's when we were introduced to Terry Brown, who owned a studio called Toronto Sound.

Terry Brown (producer): Originally, it was just another session for me. We didn't really have a relationship at that point. We had just met. We only had three days to put all the mixes together and cut three new songs. There was no budget. They were not signed to a real label. But I gravitated towards Geddy's amazing vocals and Alex's really stunning guitar playing. I thought they were incred�ibly talented.

Geddy Lee: When we came back and heard what Terry could do for us, it was an epiphany. We sounded like we rocked. That's what we wanted to sound like.

It was 1974 and RUSH already had a local following in Toronto, including friend Bob Roper, who worked for A&M Canada.

Bob Roper (former Ontario promotional representative with A&M Records): I had seen RUSH at various Yonge St. bars and got to know the guys. I was given five or six copies of their album and someone said, 'You run around to radio stations, right? Would you help us out with this because we're doing it on our own?' I said, 'Sure, why not. As long as A&M doesn't find out and I get my ass fired, everything is fine.'

Donna Halper (former music director at WMMS radio sta�tion in Cleveland): I'm sitting up in my office in 1974 and I get this package in the mail. It's addressed from a Bob Roper of A&M Canada. Roper had sent me stuff in the past and he had a good ear. He said, 'This is kind of a homegrown production. Our label is not going to sign them. But I hear something and I want to know if you hear something too.'

Bob Roper: I liked the band. I liked them as guys. I knew they had made that record in the middle of the night for a buck and a half.

Donna Halper: I find this long song called 'Working Man.' I listened to the song and said, 'My God, this is a perfect Cleveland record.' I just knew it immediately. In fact, I took it downstairs to the deejay who was on the air at the time, a guy named Denny Sanders.

Denny Sanders (former WMMS deejay): I'm on the air in the evening. Donna comes down to the control room. She says, 'I have to tell you about this new album. It's a new act called RUSH from Canada.' So while I had another record on the air, I put it up on cue and pecked around a little bit listening. I remember thinking, 'Boy, this is good. Very powerful.' I said, 'Let's try it out. Let's put "Work�ing Man" on the air.' I didn't say who it was. It was in the middle of the set, so I didn't introduce it. Well, the phones just lit up.

Cliff Burnstein (former executive at Mercury Records): I was doing national album promotion in 1974. I was working in Chi�cago, calling all the album rock stations. That album came into the label on a Monday morning. Ira Blacker was the agent in New York, I believe working at an agency called ATI. The band was signed to a booking agency and he was representing them to try to get a U.S. deal. He sent it to the head of our company, Irwin Steinberg. I get this note, 'Go to the president's office and pick up this album by RUSH.' Normally, this would be sent over to the A&R (artists and repertoire) department. But the guys in A&R were all travelling or something. And for whatever reason, this was deemed to be some�thing that needed a really fast answer. Why? This is the part I still don't know. I have no idea.

Ira Blacker (former agent and RUSH co-manager): The ur�gency was something I created. You know, 'Here's a band taking off!' Was it really taking off? Not really.

Cliff Burnstein: The president of the company wasn't there ei�ther. But he had his assistant give me the album to listen to and evaluate. So I listen to the first side. I'm immediately blown away. Then I made a couple of calls. I call Donna Halper to see if she had heard of RUSH because the note said that they were selling big in Cleveland. She says, 'RUSH? Huge! We're playing them here, absolutely. It's sold like two or three thousand copies in Cleveland.' She says, 'Wait till you hear "Working Man." It's unbelievable.' I say, 'Well, I'm looking forward to that. I'll turn the record over now.' And then it's like, 'Yeah. I'm in fucking power trio heaven.' It's now like 10 in the morning. I go over to the president's assistant and say, 'Tell the boss I think this thing is great and we should definitely sign it.' A deal was made by the end of the day. I don't know why it had to be done right away.

Geddy Lee: We were about to sign a deal with Casablanca re�cords, the label that signed KISS. They had made an offer and Cliff heard about it.

Cliff Burnstein: I don't remember that. It could well be. By the way, if a guy is at a booking agency, you already know that he's hawking, OK? It wouldn't be unreasonable to say that some�one else already has a bid on this. Maybe it was Casablanca. Who knows, there may not have ever been a Casablanca bid. But for whatever reason, based on what Ira said, the president of our com�pany thought there was a lot of urgency involved here.

Ira Blacker: There was no bid from Casablanca. I might have told Irwin that Larry (Casablanca president Larry Harris) was going up (to Toronto) to see the band. But, frankly, there was so much juice on the situation, I wouldn't have needed to. I made the deal with Irwin that day and put them on the road solidly. I mean, I booked their asses off. I put them on every ATI date I could find.

Geddy Lee: For guys who had been in the bars for three, four years, it was kind of dizzying.

Cliff Burnstein: It was pretty unusual. Think about it. The re�cord comes in. You've never heard of the band before. You've never seen the band. You haven't done any research, exploratory work, nothing. You've never met the band. You don't know the managers. You just know this one agent who is representing this thing. That's all you know. You know nothing else. So you're going completely on the sound of the record, the sound of the band and the fact it's selling hot in Cleveland off of airplay on 'MMS.

The deal with Mercury was about to change their lives. But not everyone was comfortable with change. Drummer John Rutsey, who died in 2008, was having health problems and second thoughts.

Alex Lifeson: John suffered from juvenile diabetes. He was very insecure about it. He had periods where he would become very ill and he didn't take particularly good care of himself at that time.

Geddy Lee: He wasn't sure he could deal with the rigors of be�ing on tour and being a diabetic. I can't really put it into words what he must have felt in those days. But he wasn't all in, if you know what I mean. He had reservations. So it was kind of decided amongst us that maybe we should move on without him. He was not unhappy with that decision.

Alex Lifeson: We also had some musical differences. Geddy and I wanted to explore something a little more complex and pro�gressive. John preferred the straight ahead rock stuff.

Geddy Lee: He had his own demons at that time. I remem�ber even during the recording sessions, he was very moody and wasn't always up for doing what was necessary. I think part of him wanted to do something else, frankly. I'm sure he had regrets to a certain degree. How could you not? But I don't think he was bit�ter about it or felt he made a mistake. He was being honest with himself the whole time.

Disillusioned by the mindset of other musicians in England, meanwhile, Neil Peart was back in St. Catharines, working with his father at the farm equipment dealership. That's where RUSH man�ager Vic Wilson showed up one morning to invite Neil out for lunch and ask him to audition.

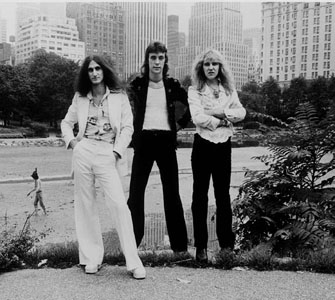

Alex Lifeson: We were in a rehearsal space in Pickering. Neil came out. He had this little tiny kit of Rogers drums.

Geddy Lee: Neil had the drums hanging out of this little car he drove up in.

Neil Peart: My mother's Pinto.

Alex Lifeson: He was a tall, gangly guy with very short hair. He was very nerdy looking. My first reaction was, 'Oh my God, this guy is definitely not cool enough to be in our band.'

Geddy Lee: He looked so goofy. You have to remember, Alex and I both had really long hair. We had just signed an American record deal. We thought we were groovy. We thought we were cool. It took us years to realize how uncool we actually were.

Neil Peart: It was such a dense day. We were feeling each other out. I didn't feel anything was at stake at first.

Geddy Lee: He had a lot of drums. But I had never seen any�one use such small bass drums. They sounded like machine guns when he played. Because he's so big and the bass drums were so small - I think they were like 18 inches - he looked enormous behind that kit. Then it was like, 'Holy fuck, this guy is pounding the drums like nobody's business.'

Alex Lifeson: I think I probably had more reservations than Geddy did at first. I was a little slower, a little bit more cautious.

Alex Lifeson: I think I probably had more reservations than Geddy did at first. I was a little slower, a little bit more cautious.

Geddy Lee: Alex was upset with me because half way through the first jam, I knew I was not letting this guy go. So I started talk�ing to him about joining the band and we still had another guy to audition. We had promised that we would not talk to anyone until we'd heard them all.

Alex Lifeson: Geddy definitely felt connected to Neil from a rhythm section point of view right away. He really enjoyed playing with him that day.

Geddy Lee: Jesus, I wanted to grab his leg and say, 'You're not leaving.' He was that good. Seriously, he was the best drummer I had ever heard.

Alex Lifeson: We really stretched the day out. I think we prob�ably spent six or seven hours playing and sitting around talking. He was amazing. He played like Keith Moon. He hit his drums really, really hard.

Geddy Lee: Alex and I did a riff, the beginning of the song 'An�them.' John never really dug it. But Neil just slotted right into it. And it was just like, 'Oh, yeah. This is the dude.'

Neil Peart: I remember us all lying down on the floor among the gear in the rehearsal room talking about Monty Python, talk�ing about Lord of the Rings, but especially it was the humour right away that we shared that made me really want to be in that band. That was the remarkable thing. Musically, we gelled and shared the energy. But we could also make each other laugh.

Neil joined the band on July 29, Geddy Lee's birthday. RUSH's first U.S. concert would take place at the Civic Arena in Pittsburgh, PA on Aug. 14, 1974. The band opened for Uriah Heep and Manfred Mann.

Geddy Lee: We didn't even have road cases. We had our cables and stuff in Coca Cola boxes. We looked green when we arrived at our first American gig. We just looked like hicks right out of the bar, which is what we were.

Alex Lifeson: We had a dressing room that was on the other side of the building, all by ourselves. Geddy was very nervous. He had a shot of Southern Comfort before going on to warm up his throat a bit and calm his nerves.

Geddy Lee: I had read that's what Janis Joplin and all these rock singers did. They had this little shot before they went on. So schmuck that I was, I thought I'd do the same thing although I had never drank Southern Comfort in my life.

Alex Lifeson: It's funny because it just hit him in such a hard way.

Geddy Lee: By the time I had regained my senses, our 26 min�utes were up. We were basically playing while people were still coming in and finding their seats. But it didn't matter. We were playing the big room, as they used to say. We felt like a door was opening for us. It really was exciting.

Alex Lifeson: I remember being up there and looking around and thinking, 'Oh my God, I can't believe this.' The biggest gig we did before that was at the Victory Theatre, opening for the New York Dolls. That was like only 1,200 people or something. The Pittsburgh show was like 13,000 or 14,000.

Neil Peart: That show had an unbelievable magic to it. I'll never forget standing at stage left when Uriah Heep was on and the lights and the rock star vibe of it all was so real. I think they were playing a song called 'Stealin' ' and then the dome opened. That was our first experience of the big time.

Alex Lifeson: The pittance we made that night, I think $750 for that show, our road manager left on the roof of the car when we drove away. We were at a red light and somebody said, 'Hey, you have something on your roof.' He got out. It was in like one of those moneybags. Fortunately, it didn't blow away. Otherwise we wouldn't have been able to stay at the crappy Holiday Inn we were staying at, all in the same room.

Geddy Lee: We were also getting to know Neil. He had only been in the band for two weeks. He read a lot. We noticed he's dif�ferent than us. He's not as stupid as we are.

Neil Peart: Reading had been a huge passion up until drum�ming then I kind of forgot about it for a while. But when you're on tour, there is all this empty time. Reading became the first outlet and an intake at the same time.

Glen Peart: When Neil dropped out of high school, I went and talked to the teacher at the time. And the teacher was very under�standing. He said, 'Well, I think Neil has tremendous capabilities. But he's wasting his time in high school because he's bored all the time.'

Donna Halper: When Neil joined the band, my recollection is that Geddy was kind of intimidated by him. That Geddy kind of set it up that Neil was much more literate and erudite than he was. The truth is, they both pretty much had the same education.

They're both actually quite bright.

Neil Peart: I think it was mutual inspiration. We really inspired each other in a lot of different ways and could not have gone for�ward but as equals.

Constant Change Is Here Today

1974-81

Studio Albums: Fly by Night, Caress of Steel, 2112, A Farewell to Kings, Hemispheres, Permanent Waves, Moving Pictures

Howard Ungerleider (lighting director): I joined the entourage in 1974. I was an agent in New York and the agency sent me up to Toronto to take over the RUSH operation and teach them what touring was all about after the Mercury deal.

Geddy Lee: Life on the road was so exciting and profound. We would drive for hours and hours. We travelled across America and Canada, thousands of miles, in a station wagon. We destroyed those poor cars.

Howard Ungerleider: We were travelling in rental cars for the first year. One day we were in Saskatchewan and Alex and I were walking around. We stumbled across this car lot that had this van, a Dodge FunCraft. It was a van that had a big roof on it so someone could sleep in it. We were both standing there looking at it and saying, 'Oh, man. Could you imagine one day having something like that? Wouldn't it be great? We could take turns sleeping in a real bed!' Eventually, we did get it.

Pegi Cecconi: I remember when they got the FunCraft. We were up in Thornhill, at the corner of Yonge and Nowhere. It was blue with a white roof. They were just so excited to be on the road.

Ray Danniels: We were trying to find our way at a time when there was no shortage of good acts and viable acts.

Geddy Lee: We played any gig that would have us. We had to. We couldn't really afford to be out there. You made so little as an opening act. You basically had to borrow money to stay on the road. And we were out there for months. But we learned so much.

Neil Peart: We would see bands that were just shameless, milk�ing the audience for every lame clich� they possibly could and judging the quality of the show by how many encores they could get. Treating the audience as consumers. We called that The Sick�ness among ourselves at the time.

Nancy Young (Geddy's wife): The one thing I give, among other things, great credit to them for is their sense of integrity and honesty toward what they did.

Neil Peart: We played for the love of it. The idea of changing songs or manipulating the audience in any way other than trying to play well was so foreign and kind of evil to us. I remember open�ing for one band and hearing them on the radio station that after�noon. They were saying, 'Yeah, we've got some new product out and we haven't played in this market for a while.' And I'm thinking, 'What are you saying? Your music is units of product and your au�dience is a market?' That's what I mean by The Sickness.

Cliff Burnstein: During that first tour, I went down to St. Louis and we had our own local promotion guy there. The two of us went out with the band to dinner. This was before the gig so it's an early dinner. Sake is offered to everybody and they're like, 'Oh, no. We're not drinking sake. We have to be really on our game when we go out there tonight to play.' These guys were so young. But they were not fucking around.

Pegi Cecconi: I've worked with a hundred bands. RUSH was always in this as a group. You just knew when you met them that they would make it. I wasn't even particularly a huge fan of their music. I certainly didn't get it until recent years. But you just knew they had what it took because they were so incredibly focused.

Howard Ungerleider: I travelled with a lot of other bands be�fore RUSH. These guys were subdued, to say the least. They weren't your typical rock stars. They weren't getting into trouble like, say, Metallica. But people still just went nuts for them.

Cliff Burnstein: I'm in the dressing room during the St. Louis show and there's - let's just call her a hot girl. She's in the dress�ing room before and after the gig. My first thought is she possibly works for the band. So I say, 'What do you do with the band?' And she says, 'Well, I was on the Uriah Heep tour but I thought these guys were hot so I decided to jump off and go with them.' Then I realized she does not work for the band. That was a very good indication to me immediately - and it became a rule of thumb for me for the rest of my career - that those groupies or superfans are the first ones to know who is out and who is in. It's very much a democratic function in the economy. They are making a choice. She was choosing RUSH over Uriah Heep. This is RUSH's fourth gig and Uriah Heep already had a couple of gold albums. But she was making the jump to RUSH. That was huge.

Offstage, the band's chemistry was developing and much of it was steeped in humour.

Geddy Lee: We started touring with KISS. We played with them for months and learned a lot about being on the road. We also learned about each other on that tour. We learned how much fun we could have with the three of us. When we were together, we were very funny. I remember Ace (KISS guitarist Ace Frehley) used to love that. He used to love having us in his hotel room after the gigs because he would just laugh his ass off.

Howard Ungerleider: Alex would actually dress up as different characters. He had the guys in KISS howling. Sometimes he would draw a face on a bag and put it over his head. Then he'd put on these sweat pants and pull them up way past his waist. He'd come out as this character called The Bag. It was very entertaining.

Terry Brown (producer): I remember one night we worked until about 4 or 5 in the morning. I crashed with my feet up on the console. They covered me in tambourines and percussion instru�ments very gently while I was sleeping at the desk. I woke up at about 6 and everything fell off and scared the hell out of me.

Neil Warnock (foreign agent): I can remember going to a club with the three guys who never ever wanted to go out with the label anywhere after a show. It was a place down on the river Thames, a very exclusive place at the time. It was full of Arab gentlemen who obviously were wining and dining there. I can still see Ged and Alex going, 'Right. Let's go through the wine list. These guys are going to regret this for the rest of their lives.' They ordered some extraordinary wines that night and kept saying, 'Nah, we don't like this one. Let's try a bottle of this or that.'

Neil Warnock (foreign agent): I can remember going to a club with the three guys who never ever wanted to go out with the label anywhere after a show. It was a place down on the river Thames, a very exclusive place at the time. It was full of Arab gentlemen who obviously were wining and dining there. I can still see Ged and Alex going, 'Right. Let's go through the wine list. These guys are going to regret this for the rest of their lives.' They ordered some extraordinary wines that night and kept saying, 'Nah, we don't like this one. Let's try a bottle of this or that.'

Howard Ungerleider: I remember one of our first shows, go�ing up to Cochrane, Ontario. I had just come in from New York. I was in a denim jacket and jeans. We're driving up and the guys say to me, 'So where's your warm clothes?' And I'm like, 'I'm wearing them.' And they were like, 'You must be kidding. If we had an ac�cident now, you'd probably freeze to death.' They made me pull the car over and get out. That was an education.

Pegi Cecconi: There are these infamous tapes, the Jack Secret tapes. Jack Secret is a guy named Tony Geranios, who's been their tech since the beginning of time. He used to do something called The Jack Secret Show. It was filmed at Le Studio in Montreal when they were doing these albums. In one of them, Alex is dressed up like Suzanne Somers but he had a moustache. Then they would pan over to Neil, who was playing an army sergeant. I only saw them once while house watching for Alex. I was on the floor (laughing) but I knew I couldn't even admit to watching them.

Matt Stone (friend and co-creator of South Park): Trey (South Park co-creator Trey Parker) and I used to throw these big Hal�loween parties. The last few became huge events, really legend�ary, like fucking crazy. They were kind of great because everyone was fucked up but they were also in costumes. So you had no idea who was there. You'd hear afterwards so-and-so was there and it would be like, 'What? That turtle was George Clooney?' Neil came to one of these parties and he came in drag. It was such a trip. I'd go around the party and whisper, 'That's Neil Peart.' You could see the reverence people have for all three of them, but in this particu�lar case, Neil, even through the drunkenness. People were really impressed that Neil was at our party.

Peter Collins (producer): One of the great moments was when we were in Montserrat. The studio and the band would go to a bar�becue on the beach once or twice a week. Alex proclaimed himself as King Lurch and would ride on a throne in the back of a flatbed truck, to and from the beach. The locals would be walking along the side of the road with goats and pots and pans. One day, point�ing at the locals, he proclaimed, 'I am King Lurch and I decree that tomorrow you shall not work!' And they looked up and said, 'We don't have jobs.'

In 1975, RUSH released their second album, Fly by Night. Later that year, the band released Caress of Steel. It nearly became their last album with Mercury.

Cliff Burnstein: It was my job to get the airplay. I couldn't get airplay in a lot of places. People would go, 'I'm not going to play this guy. His voice. I'm not going to play Geddy Lee on the ra�dio.' That's what people would tell me. Sometimes we would buy advertising on a station that wouldn't play the band. I will take credit for this idea. We'd just play 60 seconds of 'Finding My Way' or 'Working Man' - 60 seconds of one song as an ad. I tell you, we'd sell albums in that market the next day. You could make the impression with one ad.

Alex Lifeson: With Neil joining the band, Fly by Night was a departure from the first record. And it was OK. We still had some good heavy songs that were accessible.

Terry Brown: We had three weeks to make that record, from start to finish. They were on the road so I never heard any material ahead of time.

Cliff Burnstein: The first record kept turning over, a few hun�dred copies week after week. Then they quickly recorded Fly by Night and we expanded a little bit on the airplay. Now both records are selling. There was a pattern developing here that was very posi�tive.

Alex Lifeson: Then came Caress of Steel, which was much more experimental for us. At that point, we were really thinking about the whole idea of concepts.

Howard Ungerleider: I called it an art project. They were ex�perimenting. That's what RUSH does. They experiment and chal�lenge themselves.

Geddy Lee: So we went from 'Working Man' to 'By-Tor and the Snow Dog.' People didn't get the fact that it was kind of a com�edy. We did it for laughs. But everyone took it so seriously, 'Look, here is this heavy prog band.' It was a shame because the record company lost interest in us. It was obvious by the way they were treating us.

Alex Lifeson: We wanted to work in a longer format, with more dynamics, quiet parts, loud parts. We were feeling the progressive movement of the time with Yes, Genesis, King Crimson, bands like that. We were becoming more sophisticated and complex in our arrangements, or at least trying to. We were still really young.

Terry Brown: I was a big fan of (Caress of Steel). It was dark and foreboding. It wasn't a pop record. But I always had this idea that you have to look at a career as a whole. I think it was a very creative record for them to make. And when you look at their career, it was a stepping-stone to where they were going.

Ray Danniels: They have never been overly concerned with their commercial success. The trade off with them has always been that if they wanted to do something their own way, they accepted whatever success came or did not come with that.

Geddy Lee: I kept every single hotel room key that I got. Be�cause I never thought I would be in that town again. You always were waiting for the other shoe to drop. You don't actually believe you're going to be successful. We knew we were having fun and we were trying. But something in us was almost too self-protective. You'd say to yourself, 'This is all going to end. So I want proof I was in Louisville, Kentucky.' I probably still have that big bag of keys somewhere.

Cliff Burnstein: Caress of Steel obviously wasn't quite as com�mercial or as catchy. At the time, I didn't think of that as being an impediment. But we didn't get the same response when we got the record played that we did with the other two albums.

Geddy Lee: I remember Ted Nugent was going through a simi�lar down period in his career. So they packaged us together. We were playing small clubs in Texas and you name it. They were not the best gigs. It was a disheartening time.

Alex Lifeson: We called that tour the 'Down the Tubes' tour.

Geddy Lee: I remember playing a weird club in San Diego dur�ing that period. We were opening for - or maybe he was opening for us - Country Joe McDonald from Country Joe and the Fish. And it was like, 'Here we are. We are all going down the drain together.'

Neil Peart: We had three records that had done OK but cer�tainly the record company had written us off for the future. We would not have survived to make four albums in any other climate except inside a kind of a disorganized record company that let us slide along that long.

Geddy Lee: I remember one period we were holed up at the Sunset Marquis Hotel in LA between tours. We couldn't really af�ford to bring everything back to Canada. We didn't have any gigs and we were there for like a month. We got really good at the Space Invaders game in the hallway because we had nothing else to do.

Alex Lifeson: We probably lost money for the first four years that we toured. We carried a heavy debt burden for many years. There was one period in '75 or '76 where we weren't paid for like 10 months. I had a wife and a kid and rent to pay. It was a very difficult time.

Charlene Zivojinovich (Alex's wife): It was hard for me and very hard for Justin, our son, not having his father around most of the time. We just had enough to pay our bills and then maybe $20 left over at the end of the week to maybe go see a movie or treat ourselves to a pizza.

Nancy Young (Geddy's wife): It's not a life for everyone. You really have to be a certain kind of person, no matter what your partner does if they travel a lot. We had no money. I was a student. We lived on top of a Chinese restaurant. Geddy would phone on Sunday, that was the deal. And he wrote letters, which was very sweet. I still have those letters. But remember, there was no In�ternet, no email. Long distance phone calls were very expensive so he would call collect. I'd sit at home on Sunday waiting for that phone call.

Nancy Young (Geddy's wife): It's not a life for everyone. You really have to be a certain kind of person, no matter what your partner does if they travel a lot. We had no money. I was a student. We lived on top of a Chinese restaurant. Geddy would phone on Sunday, that was the deal. And he wrote letters, which was very sweet. I still have those letters. But remember, there was no In�ternet, no email. Long distance phone calls were very expensive so he would call collect. I'd sit at home on Sunday waiting for that phone call.

Alex Lifeson: That's when we started to get a lot of pressure from the label.

Geddy Lee: They wanted us to be Bad Company. We didn't want to be Bad Company.

Cliff Burnstein: I put a lot of work into the band. I didn't want to see them dropped. But there was a sentiment at the label say�ing since it's trending backwards, this may not be worth the long-term investment. Probably the way the deal was structured was it was more expensive to pick up each new album. It would cost you more the deeper you got into it. People were questioning whether RUSH could actually break through.

Alex Lifeson: That's when we kind of decided to block every�thing out and do our own thing. 2112 is all about fighting the man. Fortunately for us, that became a marker. That was also the first time that we really started to sound like ourselves.

Neil Peart: When we first talked about 2112, we heard, 'Oh, the record company doesn't want a concept album.' These words 'the record company doesn't want,' to me, were raising the hackles. But also, that's not how it works. The record company doesn't tell us how to make music. It sounds arrogant but it wasn't. It was pure innocence.

Geddy Lee: By then, we were really a band. We were bonded. It was us against the world and fuck the world if they can't take a joke.

Neil Peart: That anger really got invested in 2112.

Geddy Lee: I didn't think anyone would like it. But I loved it. I loved doing Caress of Steel, too. Mind you, when we did Caress of Steel, we were smoking way more hash oil. I really think that was part of the problem. I will say now that we did not do that while we were making 2112. We kind of straightened up a little bit. We kind of felt maybe we weren't seeing straight.

Howard Ungerleider: I think Ged used to call it the Foul Fumes of Failure.

Geddy Lee: I also can't tell you how huge it was at that time to have our producer on our side. Usually the producer puts pressure on you to commercialize. Terry did not. He wanted us to be what we wanted to be.

Terry Brown: Ultimately, you're making the band's record. You're not making your own record. It's my job to get the best per�formances and make sure we don't make fundamental mistakes when putting it together. But above all that, you have to encourage the artist.

Geddy Lee: Terry had to put up with all the shit from manage�ment and the record company. They always go to the producer. I've since been a producer. I know. That's not fun, having to tell the guy who's paying the bills why you're not going to make the record he wants you to make.

Terry Brown: My personality is such that I don't get too upset about those things. The pressure wasn't really on me. It was on the band. They had this financial burden. I felt we would make more commercial records as time went on.

Geddy Lee: Terry was an artist. And he believed in our art. He saw how passionate we were about it. He supported it. Maybe some secret side of him wished we were a more commercial band, I don't know. But I didn't sense that. He slayed the dragons while we made this crazy record. We said, 'Fuck it.' We figured we were headed down the drain anyway. So in a way, it wasn't a difficult decision.

Cliff Burnstein: Ray came in to play the new album. It was probably the winter, early in 1976. We had a big boardroom where we would have our A&R meetings and listen to music. So all the A&R people, the promotions people, the marketing people, the publicity people, all sat around this big table. They play the record. It sounds very exciting to me. They explain it was a concept and the songs all flow together. Again, very exciting.

Geddy Lee: Cliff was always in our corner.

Cliff Burnstein: I have to say, listening to 'Overture,' 'Temples of Syrinx,' I just thought, 'This is the heaviest, most powerful shit I have ever heard.' I knew there was an audience for RUSH. I knew if we could get people to hear this album, they would respond. There was no question.

Geddy Lee: He understood that bands have to develop. We had signed to do two records a year. We were making a record every six months while on the road, which is crazy when you think about it. Of course we were going to make mistakes.

Cliff Burnstein: But there was a little bit of head scratching from most of the people around that table and some real question�ing as to whether this was a direction that was going to take us any further. In fact, people were saying this will probably reinforce the backwards movement of Caress of Steel. I think there was possibly some discussion if we should even continue and put it out.

There was no need for the handwringing. 2112 would prove to be a watershed for the band - the first RUSH album to eventually sell more than 1 million copies.

Neil Peart: 2112 put us over a hump and kind of pushed those people away in a sense that they could understand: We had a gold record now so don't meddle with us.

Alex Lifeson: Even since, the record company has never had anyone in the studio when we are recording. Ever.

Geddy Lee: It vindicated our management in the eyes of the re�cord company, even though our management didn't really under�stand what was happening. They couldn't explain 2112 any better than they could explain Caress of Steel. So they just said, 'Let's leave it to them. They must know what they're doing.'

Neil Peart: Our record deal then meant that we provided a piece of music and it's art and they sell it. That's the way it's sup�posed to be.

Alex Lifeson: It really did feel like everything had just changed.

Howard Ungerleider: I remember coming home one night and having to crash over at Ged's house. His mother came up to me and said, 'So what do you think? Do you think my son is going to make it?' And I said, 'Absolutely.'

Mary Weinrib: Howie had brought a suitcase with little dollar bills in it!

RUSH soon found itself as the headlining act. The band was in demand around the planet. They practically lived on the road for the next few years, sometimes playing more than 260 nights a year.

Alex Lifeson: After 2112, our confidence was building, the crowds were building. We were headlining a lot more. We toured with Thin Lizzy and got really close to those guys. We decided to go to England to record Farewell to Kings.

Geddy Lee: 'Closer to the Heart' was a quantifiable Top 20 song in the U.K. We had a lot of fans there after that. I remember playing in Glasgow for the first time at the Apollo and they were all singing the song. I never had that experience before. And they were really loud. It was just an amazing moment.

Alex Lifeson: I remember being in the Rockfield studio in Monmouth, Wales, recording 'Xanadu,' which is an 11-minute song. We did one take to get sounds and then we played it front to end on a second take and that was the take that's on the record. That was a turning point for us. It was so exciting to be touring in England. It was so different, so exotic in so many ways.

Neil Warnock: I was actually tipped off about RUSH by a pro�moter. It must have been in '75. He and I worked on a whole bunch of different projects at that time and we were always swapping in�formation, 'Have you heard this? Have you heard that one?' He turned me on to listening to them and I thought, 'Oh my God, this is tremendous.' We started researching and there was actually quite a little bit of ground swell.

Geddy Lee: All the bands we loved were from Britain. We dreamed about working in some of those studios. And because Terry was British, and he knew his way around the studio scene, we figured we just had to go there.

Neil Warnock: I found their number to call their office and got a hold of a manager at the time, Vic Wilson. And I said, 'I'd very much like to be your agent and this is what I can get for you if you bring the band to the U.K.' He said, 'You've got to be joking. We've never heard from the label. You're the first English voice we've heard about this.' I knew we could definitely do three or four or more shows. We could put them straight into theatres, not clubs. But it was, as ever when dealing with RUSH, torturous. These guys never wanted to leave (North America).

Pegi Cecconi: Here's the thing: Europe is a pain in the ass to tour compared to the simplicity of touring in North America, where you have brand new stadiums, you drive the truck up, hotels are nice. You go to England in the early days and you were play�ing cow palaces. You are staying in little rooms. They had a road crew that just really didn't like it. And unlike a lot of bands, RUSH always cared about their crew.

Pegi Cecconi: Here's the thing: Europe is a pain in the ass to tour compared to the simplicity of touring in North America, where you have brand new stadiums, you drive the truck up, hotels are nice. You go to England in the early days and you were play�ing cow palaces. You are staying in little rooms. They had a road crew that just really didn't like it. And unlike a lot of bands, RUSH always cared about their crew.

Howard Ungerleider: When I came into the operation and had to assemble touring personnel as the band was growing, I was hir�ing people I knew. We were trying to keep this as high quality as we could given the budget we had. But anyone I hired, they just stuck around. The guys in RUSH were so phenomenal that every�one just wanted to stay.

Neil Warnock: Eventually, we got them to come over. They were surprised. They did great. I thought that we might be on a trajectory that other artists have been on - doesn't matter if it was KISS or Aerosmith or the other stuff that we were dealing with at the time - that they would tour here regularly. Not RUSH. No. They don't tour regularly. They maybe come around every four or five years with the wind in the right direction.

Pegi Cecconi: It's got to be a finite number of dates and the path of least resistance, in many ways. We could book them across North America and make way more money and not have the ex�pense of shipping over the kind of production they wanted to ship over. It was crazy the way it was done back then. But nobody knew better. I wish it were different. But when they came back from Eu�rope in those early days, breaking even was on the upside.

Neil Peart: All the touring we needed, all the work we wanted, was in North America. There was no need to go anywhere else. There was no ego need to say like, 'We need to headline in Cal�cutta.' It didn't matter.

Alex Lifeson: We recorded a lot of records in Britain. We went back to Rockfield and did Hemispheres there. It was a really busy time.

Neil Peart: Hemispheres was the one that really killed us. We had been worked too hard. When success first came along, we wouldn't say no. People want to hear us? Yeah, we'll be there. It would be, 'OK, we have 10 shows in a row. Can you do an after�noon show on this date because that show is doing well?' 'Yes, yes, yes.' 'Can you go do a six-week tour of England and then go in the studio to make an album?' 'Yes, yes, yes.' That's the point at which we really felt it.

Geddy Lee: The next flashpoint was Moving Pictures.

Ray Danniels: The first time I listened to that, I knew we were entering a whole new world. I had gone away with Geddy. I was dating his wife's best friend at the time. The four of us went away and I sat in the Barbados listening to it on a Walkman. I couldn't believe how good it was. I couldn't believe how every song on the record was so good.

Matt Stone: I grew up in a household without music. I really grew up in a weird household that didn't have any musical tradi�tion at all, so it was just a big blank slate. And like 10 million other white suburban kids, I heard 'Tom Sawyer' when I was in fifth or sixth grade and it just stood out. It was a mind-blowing experi�ence.

Geddy Lee: Things were going well. But I was really hungry to learn and hungry to experiment.

All This Machinery Making Modern Music

1981-96

Studio Albums: Signals, Grace Under Pressure, Power Windows, Hold Your Fire, Presto, Roll the Bones, Coun�terparts, Test For Echo

Neil Peart: We were really lucky in our era. Coming through the '70s, I loved the changes that music went through. People a little bit older were threatened by it and resisted it and said when punk and new wave came along, 'What am I supposed to do? Forget how to play?' But once I started to hear good new wave music, like The Talking Heads or The Police, I loved it. We wanted that to be a part of what we were doing.

Alex Lifeson: After 2112, we toyed with the idea of adding someone else to the band. But at the end of the day, we decided it would disrupt the chemistry of what we had. So we started learn�ing other instruments. Geddy really got into keyboards.

Geddy Lee: I was getting bored writing. I felt like we were falling into a pattern of how we were writing on bass, guitar and drums. Adding the keyboards was fascinating for me and I was learning more about writing music from a different angle.

Alex Lifeson: At first, we were all very excited about the extra element. It made our sound bigger. We had more impact off the stage.

Geddy Lee: When you grow up in a band like RUSH, it's very insular. There's not a lot of playing with other musicians. So you look to draw in anything that can give you a spark to write songs. At that time, it was the keyboards that were sparking me.

Neil Peart: We were young enough to adapt and free enough to adapt and absorb all those influences. Through the '80s, that was such a great time for influences, from the world music side to the synthy tech side. It went both ways. I was deep into African music at the time. But at the same time, I loved '80s dance music. They weren't mutually contradictory to me. I wanted to have both of those in our music and we did.

Alex Lifeson: At first, keyboards were used sparingly. On Mov�ing Pictures and Permanent Waves, it was still controlled. We used them efficiently, economically and effectively, I would say.

Alex Lifeson: At first, keyboards were used sparingly. On Mov�ing Pictures and Permanent Waves, it was still controlled. We used them efficiently, economically and effectively, I would say.

Geddy Lee: I think Al was a little nervous about being over�shadowed by this new sound. But at the time, he was gung ho to do it when we started. We wouldn't have done it if he wasn't.

Alex Lifeson: In my heart, I really wasn't thrilled with the way it was going. But I remained silent about a lot of my feelings at that time, to be honest. I've always been like that in the band. Geddy and Neil have stronger personalities. I felt like I'm just not going to rock the boat.

Neil Peart: That boat is a hard thing to define.

Pegi Cecconi: RUSH as a touring entity and RUSH as a band is a machine. There's a key that turns it on and no one is quite sure who holds it. It's very difficult to move that machine around.

Alex Lifeson: It wasn't until Signals that I started having real problems with the keyboards. A lot of it had to do with the way that record was coming together in the mix. There was a move�ment towards highlighting the keyboards more and making them the lead melodic instrument, taking that position away from the guitar. I just felt like the guitar had lost a little bit of its importance.

Terry Brown: We never had a conversation where Alex actually said to me, 'This is not cool. I'm worried about it.' We never had that conversation.

Neil Peart: During this last tour (in 2012), I visited the building up in Lake Windermere, where we did all the pre-production. It was the first time I had been back there in 30 years. I happened to be motorcycling along on a day off up in Muskoka and I see a sign for Windermere. I stopped my riding partner and said, 'We gotta go have a look.' The building is still there and all the memories suddenly came back of wintertime, four feet of snow, and we're in a little room all day long working on those songs.

Terry Brown: I am very aware of how bands develop and how things have to change in order to keep everyone interested. Ged wanted to be more proficient at keyboards and wanted more key�boards.

Neil Peart: The song 'Subdivisions,' for example, had been done the previous summer. We had been mixing a live album up in Quebec. And with a live album, there's not a lot to do. So we set up a little practice room in another studio and did all the writing on 'Subdivisions' then. Alex and I at that time, we were the rhythm section on a lot of those parts. Alex and I were playing together, in�teracting like a bass player and drummer would for the first time. It was great for us.

Terry Brown: I knew that I could keep the energy and the toughness of guitars, bass and drums and the keyboards would be a colour. Admittedly, it became a much bigger colour than it was in the days of 2112.

Geddy Lee: I think it was after we did Power Windows, that was the first time it was obvious that Al was starting to object.

Peter Collins (producer): On Power Windows, I brought in Andy Richards who was a heavy hitter in terms of keyboards. On 'The Big Money,' you can hear him on the intro. All these incred�ible keyboards were coming out that were completely fresh and new. They wanted a part of that. So I brought in the top guy in England to help them with it.

Geddy Lee: Andy's parts were recorded before Alex laid down the guitar tracks. So his stuff took up all this space on the record. But it also gave us all these new sounds that was exciting us.

Alex Lifeson: I like those records. I like them a lot. I'm proud of them. But it really was a lot of work for me to fit the guitar in, to feel like I could take my space among all this dense keyboard stuff that was going on.

Geddy Lee: I think he was starting to get a bit pissed off about that, that we were not being very considerate of his parts. But we looked at it as expanding the sound and musicality of our band. And, well, I guess we didn't take into consideration how much pressure he was under.

Neil Peart: At that time, recording keyboards first had been simply a logistical matter, because we were in England and would shortly be in, like, Montserrat, where the guitars were recorded. However, the flamboyant Andy Richards filled so much space that sometimes it was hard for Alex to figure out where to be. So after that, he always insisted that the guitars be recorded first.

Geddy Lee: He was always very supportive openly. But I guess secretly he was getting frustrated.

Neil Peart: There was no tension about it at the time. It was perceived by others as being guitar-lite. It only became contentious when it seemed to be threatening over time. There's never been a keyboard solo. But I think every RUSH song has a guitar solo.

Geddy Lee: There was something else going on around then. I did not feel I was learning enough from Terry anymore. And I think I was speaking for the whole band at the time.

Neil Peart: Signals was the crucible because Terry wasn't going where we were going. One song that was problematic was 'Digital Man' because it combines a ska rhythm with a deep computer se�quence. We didn't see any contradiction there. Terry Brown did.

Terry Brown: I was concerned about the direction of the band when I left and didn't make any more records with them. I felt it was heading into a direction that wasn't really my cup of tea.

Geddy Lee: The one thing we always agreed on was not stag�nating. We always felt we needed to move in some new direction. So we all kind of agreed that we needed to work with someone else.

Neil Peart: We weren't always successful. Not all of our albums or song experiments are successful in the artistic sense. But each was important and took us somewhere else.

Geddy Lee: We looked at each other and said if we can predict what Terry is going to say, we're not learning. That means we're writing our songs to please his way of doing things, which was fine up until then. But we were afraid of being stagnant.

Terry Brown: I'm not sure that I buy it completely. It certainly was a factor that was concerning them. I didn't really feel it myself. I thought we would have continued to make great records togeth�er. But then when you look at what they did after I left, I wouldn't have made those records that same way. So they needed to make a change.

Geddy Lee: He was shocked and obviously fairly taken aback. He loved working with us and we had made so many good records, so many successful records. It didn't make sense to him why we'd want to leave.

Terry Brown: I think they were a little bit frustrated by the fact that I really wasn't into electronic drums and didn't really enjoy MIDI. So hooking together hundreds of keyboards and control�ling them from one central spot really was not to me a creative endeavour.

Geddy Lee: It was very difficult to break off with him. He was a brother, a father figure. He was a member of our band in many ways. But there were so many exciting records being made at the time by different producers. New sounds, new styles. There was kind of a revolution in rock going on. We felt we were sitting on the sidelines. We were desperate to absorb all that.

Ray Danniels: They have their own vision and they need some�body who can open the doors for that to happen. They have never needed someone to be creative for them, including the people who produce their records.

Geddy Lee: Breaking off with Terry was the best decision we could have made. It was one of the hardest decisions we ever made.

And we paid for it dearly. Because the next year was an absolute fucking nightmare.

Neil Peart: We interviewed many more producers than we ever worked with.

Geddy Lee: The one thing that Terry had that so few of the people we've met since then had was integrity and responsibility. He was, as we would say, a mensch. That means the guy was a solid citizen. We had producers flying in left, right and centre, oh my God. And so many of them were schmucks, it was unbelievable.

Neil Peart: We did talk to guys who we sensed were going to come in and either be too harsh and tell us what to do or too amenable. Some of the guys, you could tell from the records they made, let people get away with stuff they shouldn't have. We were guarding against that all the time.

Geddy Lee: We endlessly scoured records for producers. The downside was I became dangerously obsessed with making the next record. I ignored my personal life. I ignored everything. It was not a smart time for me as a human.

Peter Henderson was hired to produce Grace Under Pressure (1984). Around that time, RUSH also summoned producer Peter Collins to a meeting in Providence, R.I.

Peter Collins: I was quite astonished by what I saw at Provi�dence, R.I., this massive stadium and screaming fans. When I went backstage to meet them afterwards, I was invited to give my opin�ion as to how their records could be different. Coming from the British pop world of that time, which was Frankie Goes to Hol�lywood and Yes, I said, 'I think your sound can be much more contemporary.'

Geddy Lee: We did two records with Peter Collins (Power Windows and Hold Your Fire) and then two records with Rupert Hine (Presto and Roll the Bones). The keyboards were starting to get thinned out through those two records. Rupert was pushing us away from keyboard dominance. An adjustment happened after Hold Your Fire.

Alex Lifeson: I was relieved when we started to move away from this.

Geddy Lee: But I was disappointed with the sound of Presto and I thought the songwriting was a little weak. Then we did Roll the Bones and, at that time, we weren't sure if we should work with Rupert again. I thought the songwriting on Roll the Bones was among the strongest of any record we have ever made. But the sound of that record let me down a bit.

By 1992, the grunge movement was at its apex and, once again, RUSH wanted to be part of the revolution. The solution? Getting back to their original sound.

Geddy Lee: We were loving that whole energy from Seattle and the Northwest. That pushed us in a different direction. That made us want to be a rock band again. We brought back Peter Collins to do Counterparts. I think it's a great sounding record. I was really happy with Counterparts.

Test for Echo, the band's 16th studio album, was released in 1996. It capped a period of madcap reinvention, exhaustive touring and, from time to time, jangled nerves.

Geddy Lee: Test for Echo was a strange record in a sense. It doesn't really have a defined direction. I kind of felt like we were a bit burnt creatively. It was a creative low time for us.

Geddy Lee: Test for Echo was a strange record in a sense. It doesn't really have a defined direction. I kind of felt like we were a bit burnt creatively. It was a creative low time for us.

Alex Lifeson: When we were working on Grace Under Pressure, that was tense in the studio. Things were not working out the way we had anticipated. There were moments where we blew up at each other.

Neil Peart: The tension was mutual. It wasn't internecine, is the word that occurs to me. It wasn't at each other. It manifested on all of us and rarely between us or among us in those days. There would be disagreements, certainly, but we handled them with re�spect.

Geddy Lee: There are no factions in RUSH. It's just the three of us.

Neil Peart: We've never had any storming quarrels or people dramatically racing out of the room or John Lennon punching Paul McCartney or anything like that. I'm sure he deserved it. With us, if there was controversy, it was resolved. There was a lot of pressure on us. But disagreements would be resolved because we are a three piece.

Geddy Lee: It's such a manageable number of people. You can have a meeting in the back of a car if you have to. Three is a nice number for friends.

Neil Peart: I remember talking to Stewart Copeland (drummer with The Police) not long ago and I was telling him we had been working on new material together. I told him how I brought in an idea and we talked about it, like 'Oh, I like this part but don't like that part.' And Stewart said, 'You guys really talk to each other like that?' Yeah, we do.

Ray Danniels: I think I'm the best manager for them because I know what they will do and what they won't do. And I know which issues are worth extra discussions about and which things should be left alone. So many managers use the tactic of divide and con�quer and I've never done that with these guys, nor would I ever. It's about creating consensus.

Neil Peart: Everything had to be by consensus. So we had to discuss a song or continue working on an arrangement until all of us were happy. If somebody brings an idea, it's a very vulnerable thing. They're bringing something they feel tender about. With lyrics, I learned not to bring a song in as a precious thing. I'll give Geddy a bunch of lyrics to go through. Sometimes he'll find one verse that he likes and I'll be happy as can be. And he'll say, 'Well, if I just had another one like this, or take these lines and switch them around,' I'm inspired by that, not threatened or humiliated by it. It's respectful and inspiring.